“The Mightier Our Blows, the Greater Our Emperor’s Love”: The Crusader Ideology of Germanized Christianity in the Song of Roland

There is a mysterious quality to the first literature of any ancient nation. The earliest recorded poems are those produced right at the edge between the forceful spontaneity of barbarism and the dead letter of civilization. They almost invariably reflect a primordial and manly mindset very different from that of our own time. They express the psychology and values of conquering peoples, heeding closely to the law of life, by which nations prosper or die. So it is with the Iliad of ancient Greece,the Beowulf of the Anglo-Saxons, and the Song of Roland of the French.

The Song of Roland is the French national epic and the first great piece of French literature, emerging in the eleventh century, on the back of the First Crusade to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims. The poem’s author is even more mysterious than Homer, for we do not even know his name. The Song is a vivid and powerful expression of the values of medieval European chivalry and indeed of the centuries-long clash of civilizations between Christianity and Islam, dating back to the Muslim conquests of Roman Christian Levant and North Africa.

In contrast with later criticisms of Christianity as embodying a universalist “slave-morality,” in the Song we find Christian values perfectly fused, and perhaps subordinated to, the essentially Germanic warrior ethos of the French knightly aristocracy in the form of a novel crusader ideology. The Song presents a perfect case-study of what James C. Russell called the “Germanization of early medieval Christianity” or what William Pierce called “Aryanized” Christianity.[1] The heroes of the poem are obsessed with honor, family, nation, religion, and service to the emperor. I shall present the historical Charlemagne and the values of the Song of Roland. These can help us understand both the emergence and defense of European identity in past centuries.

The Historical Charlemagne: Warlord, Christian Patron, and “Father of Europe”

The throne of Charlemagne, at his chapel in Aachen.

The Song of Roland is centered upon the myth of Charlemagne as an ideal ruler. Charlemagne (742—814) had been a great Frankish warlord whose ancestor Charles Martel had repulsed the Arab Muslim invaders at the Battle of Poitiers in 742. Inheriting a realm made up of France, the Low Countries, and western Germany, Charlemagne was more or less constantly at war throughout his long reign, with yearly campaigns of conquest and plunder against his various neighbors. He conquered a sliver of Spain from the Muslims, Pagan Saxony, Bavaria, and northern Italy. Crucially, the latter was accomplished in alliance with the pope, who crowned Charlemagne as emperor in 800, the first western emperor since the fallen of the Roman Empire.

Charlemagne’s conquests were marked by great brutality. This included radical demographic policies to subjugate and assimilate rebellious tribes. During the three decades of wars with the Pagan Saxons, Charlemagne “moved ten thousand men who lived on both sides of the River Elbe, with their wives and children, and dispersed them here and there throughout Gaul and Germany in many groups.”[2] Following victory, he made conversion and assimilation a condition for peace, demanding that the Saxons “take up the Christian faith and the sacraments of religion and, united with the Franks, would form one people with them.”[3]

Charlemagne used his victories to establish a united, Christian Europe. The churches in his empire were encouraged to follow one Roman Catholic creed, with the establishment of a school in every diocese, a single sermon collection, one rule for monks (that of Saint Benedict), and a single set of rites. The emperor was also a great patron of arts and culture, inviting scholars from all over Europe — most notably Alcuin of York — preserving and reviving crucial portions of Latin classical culture.

Charlemagne’s empire did not long outlive him, Europe being inherently difficult to keep together and the Franks having a somewhat bizarre custom of dividing up their realms among their sons. Nonetheless, Charlemagne established a critical mass of Europe as a Catholic knightly society with a Latin-speaking elite. This model would spread to all of Western Europe, creating a united cultural space, sharing similar values and whose elites could freely mingle and communicate with one another. Charlemagne’s military successes and his alliance with the Church forever sealed his reputation as a paradigmatic European ruler and indeed, in an expression already used in the Middle Ages, as the “Father of Europe” (Pater Europae).

The memory of Charlemagne was marked by the tension between Germanic and Christian values. Charlemagne was a gigantic, more-or-less illiterate northern European barbarian, maintaining concubines in addition to his often-changing wives. He loved to eat roast meat and established his capital at Aachen because of the presence of hot spring, perfect for baths. He is supposed to have said on one occasion: “We must not let leisure lead us into slothful habits: let us go hunt and kill something.”[4] His accomplishments were recorded by monkish scribes who often projected Christian piety (notably church attendance and love of the poor) and moral lessons upon their histories. Nonetheless, Charlemagne’s biographer, “the toothless and stammering” monk Notker, also emphasizes his military prowess, saying that in one battle the emperor’s men were even “iron-hearted”: “a people harder than iron paid universal honor to the hardness of iron”[5]

The Myth of Charlemagne and the Song of Roland

The bust of Charlemagne, containing parts of his body (fourteenth century).

Charlemagne rapidly became a mythical figure, as the embodiment of the ideal of Christian kingship, leading to tales being told about him without regard for historical accuracy, but expressing the values of medieval Europe. The Song of Roland is no doubt the most prominent example of the Charlemagne myth. In contrast with the early biographies of Charlemagne written by the scribes, the Song would have been performed by traveling or courtly bards, perhaps put to paper by a final master poet. Whereas the biographies seem to awkwardly fit the barbaric Charlemagne into a monkishly pious mold, the Song artfully fuses the chivalric warrior ethos with Christian zeal. As the Song’s English translators Simon Gaunt and Karen Pratt note: “the ideals this narrative espouses are those of the warrior chivalric classes and of militant Christianity during the First Crusade.”[6] While the biographies were studied by monks, the Song would have been performed before aristocratic gatherings, much as a film is watched today, “read aloud in such a way as to encourage intense emotional engagement on the part of the audience.”[7]

The Song tells of the withdrawal of Charlemagne’s army from Spain after forty years of war and of the deceitful ambushing of his rearguard, under the command of his purported nephew Roland, by the Muslims. In fact, Charlemagne only campaigned relatively briefly in Spain and his army was actually ambushed by Basques, but the Song portrays a mythical Charlemagne as the ideal European Christian ruler, tirelessly crusading against the unbelievers.

Roland, like Achilles in the Iliad, embodies the archetype of the proud European warrior, who prefers to die fighting than live with any dishonor. The poem frankly asserts that, without this apparently irrational and sometimes destructive pride, freedom from predators is impossible. Roland is assisted by, and contrasted with, his companion Oliver (much like Achilles is contrasted with Odysseus). As a famous line of the poem says: “Roland is brave [proz] and Oliver is wise” (87).[8] The poem celebrates the heroic values of European chivalry, Christian expansionism, and French patriotism, as well as having some racial overtones as well.

The Knightly Ethos

Knight, Death, and the Devil (Albrecht Dürer, 1513)

The Song contains perhaps the most synthetic statement of the knightly ethos:

Said Oliver: “My lord, companion, in my view

We shall have the opportunity to fight some Saracens.”

Roland replies: “May God grant it to us!

It is our clear duty to be here for our king:

For his lord a man should suffer great hardship

Enduring both extreme heat and extreme cold,

And be willing to sacrifice his skin and hair.

Let every man make sure he inflicts great blows,

So that no shameful song is sung about us.

The heathens[9] are wrong and the Christians are right.

No bad example will ever be set by me.” (79)

Here is the statement of a “European samurai,” so to speak.[10] Rather than the modern European quest for ever more individual equality and choice, here we have a demanding ethos of duty — unto death. On a personal level, this is the only correct outlook: to do one’s best and to set a good example, come what may, rather than complain about your fate and supposed entitlements (what, exactly, could the universe possibly owe you?). This was the attitude of the ancient Spartans, the Roman Stoics, and indeed the Christian knights of Europe.

Roland is motivated above all by a sense of honor. Again and again he rejects the idea of bringing shame upon himself, his family, and his emperor in the eyes of his aristocratic peers, his nation, and God. Roland says:

. . . My thirst for battle grows.

Let it not please Our Lord God or His angels,

That on my account France should ever lose its worth.

I would rather die than be covered in shame.|

The mightier our blows, the greater our emperor’s love. (86)

The knights identify with each other as a sacred brotherhood, as well as with their nation, their religion, their family, and their lord. The poem opens speaking of “Charles the king, our emperor great” (1). Charlemagne refers to his followers as his “children” (234). In the face of the enemy, Roland affirms that “We’ll face what comes, good or evil, together” (159). Charlemagne later pursues the fleeing Muslims with his men “rid[ing] together, bound by love and loyalty” (256). As in every Männerbund, the European knights play for high stakes as a male coalition, conquering or falling together. As a natural corollary, Roland and his knights repeatedly spurn cowards as unworthy of being associated with.

The poem in general is written in a hyperbolic epic style, as is the copious violence. Roland’s men are constantly spearing Muslims, cutting spines in two, or even slicing enemies vertically down the middle with their swords. The poet says of Oliver:

If you had seen him dismembering Saracens,

Piling dead bodies one on top of another,

You would have known what true bravery was. (147)

Holy War in the Song

The Song expresses a perfect symbiosis between Christian zeal and the chivalric ethos. The primary motivation of the conflict is ostensibly religious and political. The defeated are either converted or killed (102), while their cities are subjugated or razed. However, one may surrender voluntarily, thus becoming a vassal, converting to Christianity, and paying tribute to one’s new liege.

The Muslims are not realistically portrayed but are described as a kind of godless mirror image of knightly Christians, worshiping the abyss-demon Apollyon and engaging in pagan idolatry. The Muslims are often positively described as great men and warriors, the better to emphasize the Christians’ accomplishment in defeating them.[11]

Roland is assisted by the Archbishop Turpin, himself a great knight and one of the poem’s most important characters. The knights celebrate mass and express their mea culpas before battle, hoping to rise to heaven should they die. Turpin “commands them to strike penitential blows” (89). The bishop himself affirms that if a man lacks courage he is “better off as a monk, cloistered in a monastery”[12] (141) and that “Never will a worthy knight be taken alive” (155). After killing many foes, Turpin himself dies, and the poem celebrates him as follows:

Archbishop Turpin is dead, Charles’ warrior.

With mighty battles and most moving sermons

He dedicates his life to fighting against heathens. (166)

The very swords wielded by our heroes are said to contain priceless Christian relics. The pommel of Roland’s sword Durendal contains a tooth of Saint Peter, a drop of Saint Basil’s blood, a lock of hair from Saint Denis, and a piece of Mary’s clothing (173). Charlemagne’s sword Joyeuse (meaning “joyous,” such a sword was long used during the crowning of French kings) meanwhile contains the tip of the spear which wounded Jesus Christ. The poem adds:

French warriors must always remember this.

For this is why their war cry is “Monjoie!”,

And why no race can hold out against them.

Christian victory over the Muslims, and indeed victory in battle in general, is understood to be an expression of the will of God. Christianity supported the warriors, both in life and death, while the warriors fought not only for their own honor and power, but to defend and expand Christendom.

“Sweet France”: Nationalism in the Song

Nationalism is often considered a modern phenomenon and, indeed, there is no doubt that the modern development of mass literacy, the media, and telecommunications fostered the development of national consciousness. The nation-state was also, quite explicitly, a political project, governments quite rationally seeking to cultivate a sense of national identity as the basis of civic solidarity.[13] It is however striking to see that already in the Song of Roland, in the eleventh century, we find the foundational French poem absolutely saturated with patriotism and love of France.

The poet is constantly waxing lyrical about “sweet France” (dulce France) and the “Frenchmen from France, their homeland” (65). When Roland lies dying, he reminisces about the lands he has conquered, his lord Charlemagne, and “sweet France and . . . his kinsmen” (176). As so often, we find patriotic and familial feeling joined at the hip. There is already a sense of national solidarity. If Roland fails:

The French will die, causing France to be bereft. (75)

The French will die and France will be dishonored. (77)

The poet’s France is above all a nation of warriors. The Muslim speak of “the arrogance of France, the renowned” (244) and say that “Of all peoples, yours is by far the boldest” (126). As ever, modern historians seem to underestimate the existence of not only tribal, but national and patriotic sentiment in past times.[14]

The tale of Roland indeed proved popular throughout medieval France. Many people named their children Roland and Oliver. Pilgrimage routes emerged to the purported sites of Roland’s battles (indeed a natural gap in the Pyrenees on the Franco-Spanish border is known as Roland’s Breach). Many churches were decorated with sculptures and images portraying episodes from the Song of Roland (most notably at the cathedral of Chartres, southeast of Paris). Gaunt and Pratt observe: “references to the Roland in a wide range of other works (including lyrics, romances, and historical documents), as well as visual representations and adaptations of the story in other languages, suggest that the legend had a vibrant and popular oral as well as written tradition.”[15]

Women as Chivalric Prize in the Song

God Speed! (Edmund Blair Leighton, 1900)

Women play a prominent role as the prize of chivalric ideology. A knight who has boldly risked his life and been victorious can hope to earn a reputation, land, a wife, and a peaceful retirement (44, 251). Ganelon, the European knight who betrays Roland to the Muslims, is given two precious brooches to give to his wife (60). Conversely, when the men die, the wives pay the price. During the battle:

Many good Frenchmen die in the flower of their youth:

Never again will they see their mothers or their wives . . . (109)

After he slices a Muslim’s head in two, Oliver says:

. . . never to your wife, nor to any lady that you know,

In the kingdom from which you hail will you boast

That you took away even a pennyworth of my wealth,

Or did any harm to me, or anyone else. (146)

The poet even says that one of the best Muslim knights, Margarit of Seville, oozes sex appeal:

His good looks make him popular with the ladies:

No woman can see him without her face lighting up;

When she sees him she cannot help but smile. (77)

Knightly society was clearly one in which bold and successful aggression led to material and sexual rewards for men. Men could be successful if, and only if, they risked their lives together and acted as one, necessarily overlooking the prospect that they might leave their wives husbandless and their families fatherless. Following his final victory, Charlemagne himself takes the Muslim queen to be his wife, although interestingly the poet insists that her conversion to Christianity had to be voluntary.

Racial Identity in the Song

The conflict in the Song is not primarily racial but religious. This is symptomatic of the steady decline of biopolitical thinking in the West since the fall of ancient Greek city-states, to be revived only in the modern era with the Europeans’ colonial encounters with different races and, especially, the nineteenth-century triumph of Darwinism.

Nonetheless, the conflict in the Song is partly racial and ethnic. The various tribes making up the Muslim armies — notably Arabs, Saracens, and Berbers — are described. One particularly godless and treacherous Muslim, Abisme, slayed by Archbishop Turpin, is described as “even darker than the blackest molten pitch,” (114). The Muslim forces also contain a contingent from Ethiopia, of which the poem says the following:

Ethiopia, one of those accursèd lands.

He [Marganice, a Muslim] governs the race of black men;

They have huge noses and flapping ears . . . (143). . . the accursèd races

Who’re blacker than the blackest of ink,

With only their teeth showing any whiteness. (144)

The Song then certainly reflects Europeans’ long-standing fascination and, often, revulsion for the physically distinct and alien darker races. The exaggerated physical features are also no doubt part of the poem’s hyperbole in general.

The poem’s racial dimension is not systematic, nor does it predominate as a theme. Marsilie’s son Jurfaleu is described as “the Blond” (142) while Geoffrey, a hero in the later portions of the poem, is described as having dark hair and olive skin (284). As a matter of fact, the racial boundary between the Islamic and Christian worlds is by no means absolutely clear-cut. North Africa, Asia Minor, and the Levant were once part of the Christian Roman Empire, and northern Europeans Celts and Visigoths settled in these regions in antiquity.

Nonetheless, the conflict between Christianity and Islam in effect raised up a genetic barrier between Europe and the Middle East and North Africa, while at the same time favoring interbreeding within Europe. Christianity has in this sense, quite unintentionally, fostered the distinctiveness and homogeneity of the European gene pool or, we could say, the coherence of the white race. Perhaps we can speak of a “ruse of history” in this respect.

Conclusion: The Crusader Spirit

The Surrender of Granada (Francisco Pradilla, 1882).

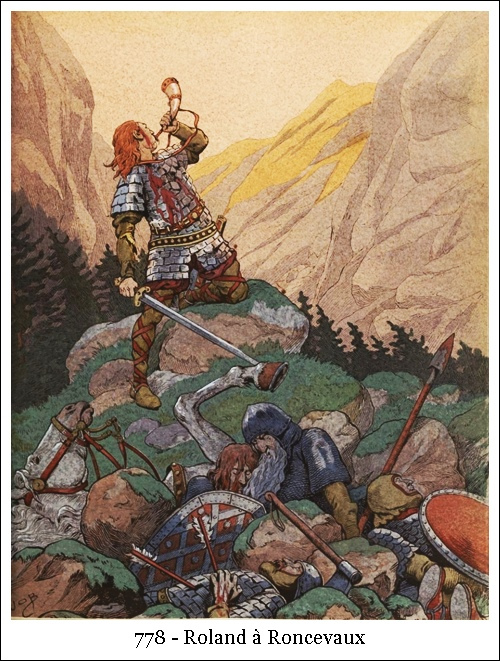

After slaying innumerable Muslims, Roland’s forces are gradually wiped out. Roland blows his elephant-tusk horn with superhuman strength, exploding the veins of his temples and warning far-away Charlemagne. As the emperor returns to Spain, an angel tells him: “God knows that you have lost the flower of France. You can exact revenge on this criminal race” (179). Charlemagne pursues the Muslim forces, who are defeated by him or drown in a river. The Christians capture the Muslim city of Saragossa, after which:

A thousand Frenchmen thoroughly search the town,

Including its synagogues and its mosques.

With iron hammers and wielding hatchets

They smash the statues and all their idols. . . .

Then they take the heathens into the baptistery.

If any of them dares to oppose Charles,

He has them hanged or burned or slain.

They have baptized a good hundred thousand

True Christians, all except the queen;

She will be taken as prisoner to fair France:

It is the king’s aim to convert her through love. (272)

The traitor Ganelon was then humiliatingly beaten by the common folk (137, 276) and tried by single combat. His champion being defeated, Ganelon was then executed with the greatest pain possible, by being torn apart by horses, while thirty of his relatives were hanged, punishing his entire genetic line. Like the Odyssey, the poem affirms a grisly form of collective, kinship-based justice against treason. The poet says: “Traitors must not live to boast about their deeds” (296). He also quotes the proverb: “Traitors bring death on themselves and others” (295).

In the nineteenth century, the Song of Roland rose to prominence as the foundational classic of French literature, frequently recited in wartime. To this day, the Song is read by French schoolchildren (conservatives still have a voice in the teaching of French literature, for instance also including the memoirs of Charles de Gaulle as part of the curriculum). However, one wonders for how long. Gaunt and Pratt indeed note that “Modern readers may understandably balk at the poem’s questionable ideology.”[16] Teaching the Song of Roland to a class of Muslims and/or infantilized native French students must not be easy. As ever, maintaining the sensitivities of multiculturalism and egalitarianism will mean the tearing down of traditional Western culture.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, the values embodied in the Song of Roland are what enabled Europe to survive and thrive in the Middle Ages. A martial Christian spirit saved Europe from Islamization at Poitiers, animated Byzantium’s defense against Islam for 1000 years, and inspired the temporary reconquest of the of the Holy Land during the Crusades and the permanent reconquest of Spain.

Our ancestors were not animated primarily or consciously by a racial conception during the Middle Ages. Nonetheless, it is striking that it was precisely late-medieval Spain which pioneered the practice of limpieza de sangre in the wake of the Reconquista, finally expelling the Muslims and the Jews (apart from the crypto-Jews, labeled New Christians or Conversos) from the Iberian Peninsula. Ethnic and racial conflicts with Jews and Arabs could not help but resurface even when these nominally converted to Christianity — the basic narrative of the Inquisition.

Dominque Venner would later rightly say “the brave Roland seems to be the brother of the divine Achilles. . . . The Frank and the Achaean are practically interchangeable.”[17] Both the Iliad and the Song of Roland are forthright celebrations of the manly pride, virility, honor, and violence necessary to sustain a nation’s freedom. We can even consider the Song to be France’s Iliad in miniature. Certainly, reading the Song, one can agree with Venner’s claim that “the spirit of the Iliad is like an ever-renewing and inexhaustible subterranean river” always underlying European civilization.

The Song of Roland’s ending is bittersweet. Charlemagne’s victory cannot bring Roland and Oliver back from the dead. The poet observes: “A man learns a good deal from intense suffering” (184). The poem concludes with angel Gabriel commanding Charlemagne to go to on the march again to save fellow Christians in another land from heathen attackers. The emperor laments: “Oh God, my life is full of toil!” (298). The European crusade never ends.

Bibliography

Einhard and Notker the Stammerer, Two Lives of Charlemagne (London: Penguin, 2008).

Gaunt, Simon and Pratt, Karen (trans.), The Song of Roland: And Other Poems of Charlemagne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Short, Ian (trans.), Introduction, La Chanson de Roland (Paris: Librarie Générale Française, 1990).

Notes

[1] James C. Russel, The Germanization of Early Medieval Christianity: A Sociohistorical Approach to Religious Transformation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996). This work is remarkable in grounding the study of history in evolutionary theory. William Pierce, “Who We Are #18,” in Who We Are (Sandycroft: 2016).

[2] Einhard, Life of Charlemagne, 7. The policy recalls that of Xerxes in ancient Persia. Charlemagne’s first biographer, Einhard, also records that after war with the Pagan Avars: “How many battles were fought, how much blood was shed, is attested by Pannonia, empty of all inhabitants, and the place where the palace of the Khan was, is so deserted that there is scarcely a trace of any human dwelling there” (Life, 13).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Notker the Stammerer, The Deeds of Charlemagne, 2.17.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Simon Gaunt and Karen Pratt (trans.), Introduction, The Song of Roland: And Other Poems of Charlemagne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), xi.

[7] Ibid., x.

[8] Numbering refers the relevant chapter of the poem, not the verse number. Proz, or modern French preux, can also be translated at “valiant” and in fact expresses many values of medieval chivalry.

[9] I have chosen to translate paiens as “heathen,” rather than the more neutral “pagan,” for the poem portrays the Muslims as godless demon-worshipers.

[10] On the samurai ethos, see Yamamoto Tsunetomo, Hagakure: The Secret Wisdom of the Samurai (Tuttle, 2014). The Hagakure is a uniquely radical statement of the ethic of service and self-sacrifice for one’s lord and clan, and can be profitably read by Westerners. It could have been written by a Spartan, had the Spartans ever been interested in writing.

[11] e.g. one Muslim is described as follows: “Had he been a Christian, he would have been a great hero” (72), and another: “He is tall and takes after his ancestors” (232). The often superficial differences between the two warring sides again appears similar to that in the Iliad.

[12] Forcible “retirement in a monastery” was one of the favorite ways of getting rid of troublesome individuals in the Middle Ages.

[13] On which see Plato, Aristotle, the American Founding Fathers, and Tocqueville, among many others.

[14] Ian Short, who translated the Song into modern French, writes: “How can we reconcile the mentions of ‘sweet France’ . . . with the evidence gathered by historians according to which there was no national feeling in France before the reign of Philip II [1180-1223]…? The Song of Roland has certainly not shared with us all its secrets.” Ian Short (trans.), Introduction, La Chanson de Roland (Paris: Librarie Générale Française, 1990), 20.

[15] Gaunt and Pratt (trans.), Introduction, Song of Roland, x.

[16] Ibid., viii.

[17] Dominique Venner, Histoire de tradition des Européens: 30 000 d’identité (Monaco: Du Rocher, 2011),71.

Comments are closed.