Leonard Bernstein and the Jewish Cultural Ascendancy – PART 2

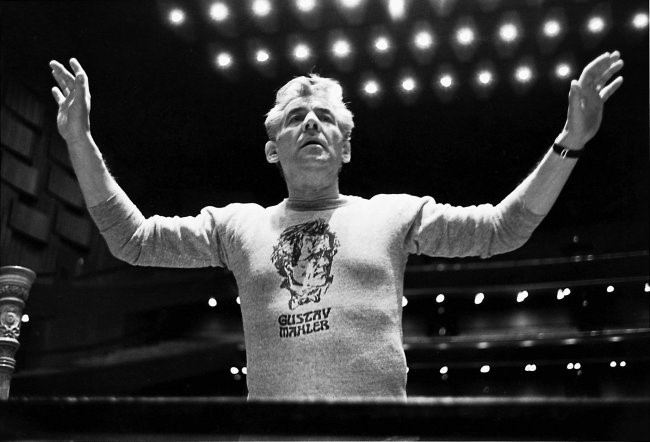

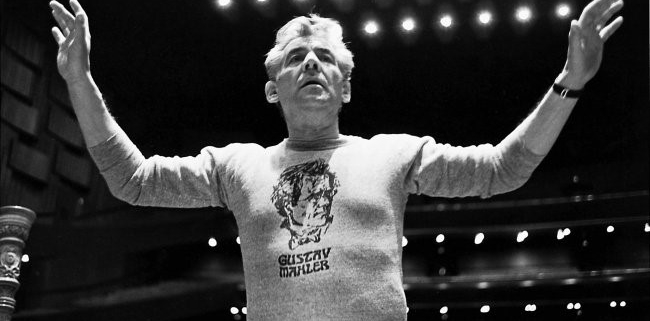

Bernstein’s Mahler obsession

I have previously examined the tendency of Jewish intellectuals to use their privileged status as the self-appointed gatekeepers of Western culture to advance their group interests through the way they conceptualize the artistic and intellectual achievements of Jews and Europeans. Jews have long used their cultural dominance to construct “Jewish geniuses” to enhance ethnic pride and group cohesion (think Einstein). In this endeavor, Jewish music critics and intellectuals have transformed the image of the Jewish composer Gustav Mahler from that of a relatively minor figure in the history of classical music at mid-twentieth century, into the cultural icon of today. The tendency among Jewish intellectuals has been to overstate and ethnically-particularize Jewish achievement, thereby making it a locus for ethnic pride. Meanwhile, European achievement is downplayed, or where undeniable, universalized and thus neutralized as a potential basis for White pride and group cohesion.

Leonard Bernstein played a leading role in the development of the Mahler cult and the movement of the composer’s music to the center of the classical repertory. The proliferation of performances of Mahler’s music in the United States between 1920 and 1960 can be ascribed to the combined efforts of Bernstein and a coterie of Jewish advocates like Bruno Walter, Arnold Schoenberg, Theodor Adorno, Aaron Copland, and Serge Koussevitzky. Lionizing Mahler as the saintly Jewish victim of European injustice, the Jewish composer Arnold Schoenberg “canonized Mahler as ‘this martyr, this saint’ and in a Prague lecture in March 1912 announced: ‘Rarely has anyone been so badly treated by the world; nobody, perhaps, worse.’”[1] Frankfurt School music theorist Theodor Adorno later took up this theme, affirming that:

Mahler’s tonal chords, plain and unadorned, are the explosive expressions of the pain felt by the individual subject imprisoned in an alienated society. … They are also allegories of the lower depths of the insulted and the socially injured. … Ever since the last of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen Mahler was able to convert his neurosis, or rather the genuine fears of the downtrodden Jew into a vigor of expression whose seriousness surpassed all aesthetic mimesis and all the fictions of the stile rappresentativo.”[2]

Bernstein likewise conceptualized Mahler as a cruelly persecuted and alienated Jew torn apart by dualisms: “composer/conductor, Christian/Jew, sophisticate/naïf, provincial/cosmopolitan — all of which contributed to the musical schizo-dynamics of his texture, and his ambivalent tonal attitudes.”[3] Bernstein advocated for Mahler with missionary zeal, introducing the symphonies to audiences from New York to Vienna. He considered Mahler “the twentieth century’s musical prophet, whose extremes spoke for the times, and thought his symphonies constituted ‘as sacred a bunch of notes as Brahms’s symphonies.’”[4] While all Mahler’s works were available singly on recordings, it was Bernstein who first recorded the complete set of symphonies.

Mahler was not standard repertoire in 1960, and the composer was not part of the generally acknowledged pantheon of great composers. He does not, for instance, feature in the top twenty leading composers compiled by Charles Murray in his book Human Accomplishment. Prior to Bernstein’s advocacy, Mahler’s larger symphonies, nos. 3, 6, 7, 8 and 9 were rarities in American concert halls. Mahler was considered “excessive” and “decadent” by influential critics and performers.[5] Shawn notes that:

Early European performances of Mahler had met with similarly mixed reactions. During the Nazi era … a reviewer could simply write that Mahler’s work exhibited “the inner uncertainty and deracination of the superficially civilized western Jew in all his tragedy.” In the postwar years, when anti-Semitic writing was banned, the standard line that Mahler’s was “a tragic case” remained, the cause now being that he was “a man of a more effeminate eastern type … [who] had succumbed to the magic of the German national character.” These supposed characteristics were still noted in mid-century European criticism, which deployed a kind of code for the presumed inherent weaknesses of people of his background (and which resembled those frequently levelled against Bernstein’s music). Mahler biographer Jens Malte Fischer lists them as “eclecticism and triviality … the gap between intention and ability, … the hankering after empty effects… the imitation of all forms and styles… shallowness and saccharine sweetness.”[6]

Many commentators noted the depth of Bernstein’s identification with the composer and described his uncanny feeling while conducting Mahler that he was performing his own music. Bernstein’s own execrable Third Symphony (Kaddish) is said to bear “the imprint of his identification with Mahler in its intensity, overt emotionality, extremes of contrast, and prophetic tone.”[7] As Mahler’s symphonies stretched the idea of what a symphony can be, so did Bernstein’s three excursions in that form likewise challenge traditional notions of symphonic structure.

George Gershwin

Before his ethnocentric infatuation with Mahler, Bernstein had, as a young man, experienced an “almost eerie sense of identification” with the Jewish composer George Gershwin.[8] He was particularly taken with Gershwin’s jazz-infused musical language, and his senior year thesis at Harvard “took as its central proposition the bold (an unHarvardian) notion that jazz was the first truly American music to have penetrated into the soul of the people to the degree that it could constitute the foundation of a national idiom.”[9] In making his case, “he dismissed many nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American [i.e. gentile] composers in such general terms that one exasperated faculty reader scrawled on the manuscript: ‘What sweeping criticism! I wonder what critics in 1975 will have to say on young American composers of 1938!’”[10] Gershwin’s incorporation of jazz elements into his music directly influenced Bernstein’s own compositional style in works like Fancy Free, the early musicals, the Masque section of the Age of Anxiety, and Prelude, Fugue and Riff.

Bernstein became increasingly politicized in the early to middle 1960s, not only in his public life and outlook but also in his musical analysis. This is manifested in his attribution to Mahler of superhuman powers of prophecy. In 1967 Bernstein hyperbolically declared that it was:

only after we have experienced all this through the smoking ovens of Auschwitz, the frantically bombed jungles of Vietnam, through Hungary, Suez, the Bay of Pigs, the farce-trial of [Soviet dissidents] Sinyavsky and Daniel, the refueling of the Nazi machine, the murder in Dallas, the arrogance of South Africa, the Hiss-Chambers travesty, the Trotskyite purges, Black Power, Red Guards, the Arab encirclement of Israel, the plague of McCarthyism, the Tweedledum armaments race—only after all this can we finally listen to Mahler’s music and understand that it foretold all.[11]

It was only after the musical world had endured such events that, Bernstein insisted, it could “finally listen to Mahler’s music and understand that it foretold all. And in that foretelling it showered a rain of beauty on this world that has not been equaled since.”[12]

For Bernstein biographer Barry Seldes, the bulk of the Mahler-consuming public in the 1960s and 1970s were “preoccupied with existential and Freudian reflections on the individual’s isolation and spiritual discontent.” This generation, he contends, felt a need to reconnect with “the artistic, and musical culture of pre-fascist Europe and to express empathy with the victims of the European catastrophes.”[13]

Of course, such a representation of the public’s love of Mahler’s music cannot be taken at face value. Expressions of love of Mahler may well involve extra-musical motivations — not only ethnic pride among Jews, but also, given the highly politicized context in which Mahler was presented as a victim of anti-Semitism, a desire to advertise one’s political rectitude and moral purity. These latter motivations would be common among Jews and non-Jews alike.

Bernstein never failed to take advantage of major events to promote Mahler. Following the 1967 Six-Day War, Bernstein performed Mahler’s Second Symphony with the Israel Philharmonic at an outdoor concert on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem, an event that Yitzhak Rabin described as the single greatest experience of his life. And after the Kennedys were assassinated, Bernstein (inevitably) offered up Mahler as a memorial.

Alongside Mahler, the ethnocentric Bernstein championed other Jewish composers from the podium including, most notably, Gershwin, Copland and Blitzstein. By contrast, he declared “I hate Wagner, but I hate him on my knees” – a grudging acknowledgement of the scale of German composer’s achievement.[14] [15]

Conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic

Bernstein regularly programmed Mahler while conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic. He was offered the chance to conduct the orchestra in 1947 as a symbol of Austria’s “denazification.” Bernstein was reluctant, and it took a massive financial inducement to secure the appointment. While he eventually “fell head over heels for the city itself: its orchestra, its cultural atmosphere, its certain Gemütlichkeit,” Bernstein claimed to be “profoundly disturbed by the anti-Semitism within it.”[16] The sound of crowds shouting in German, he wrote, “makes my blood run cold.” By his own reports the orchestra “was still 60 percent Nazi” at the time of his appointment. Jewish music writer Norman Lebrecht marvels at Bernstein’s ability to succeed as a guest conductor of the Vienna Philharmonic, “triumphing as a Jew in what many regard as the center of anti-Semitism.”[17]

After his appointment, conflict arose immediately over programming, with Bernstein recalling how “They wanted Bach, Mozart, and Schumann, which is silly.” Bernstein was instead determined to march Mahler back into Vienna as a “second wave of liberation, a musical Marshall Plan.” One of Bernstein’s biographers observes that: “Bernstein’s chief goal in Vienna was to restore the music of the great Jewish composer Gustav Mahler — music that Hitler had banned.”[18] Burton notes how he

tackled three Mahler symphonies in quick succession with the Vienna Philharmonic, beginning with the Fifth, which, like the Third, the following week, had not been performed by the Philharmonic in Vienna since the Anschluss in 1938. As the Wochenpresse tartly observed, “until now the Philharmonic did Mahler only in extreme emergency cases.” Despite their success with the Ninth the previous year, Bernstein felt a wave of hostility from the orchestra toward Mahler’s music. “They didn’t know Mahler. They were prejudiced against it. They thought it was long and needlessly complicated and over-emotional. In the rehearsals they resisted and resisted to the point where I did finally lose my temper because in God’s name this was their composer as much as Mozart was, or Beethoven, who had come from much further away.”[19]

Despite his apparent success with the orchestra, Bernstein retained an ambivalent attitude to Vienna. He wrote to his parents in March 1966: “I am enjoying Vienna enormously — as much as a Jew can. There are so many sad memories here; one deals with so many ex-Nazis (and maybe still Nazis); and you never know if the public that is screaming bravo for you might contain someone who 25 years ago might have shot me dead.”[20] Bernstein was criticized by several Jewish colleagues for having conducted the former supporters of Adolf Hitler who played in the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, and for having fraternized with the conductors, and unapologetic National Socialist German Workers Party members, Herbert von Karajan and Karl Bohm. This contrasted with the violinist Isaac Stern and pianist Arthur Rubinstein, who had “shunned these former Nazis.”[21]

Bernstein conducting Mahler with the Vienna Philharmonic

In August of 1987, the sixty-nine-year old Bernstein was still conducting the Vienna Philharmonic in Salzburg. On an evening off he sat through a performance of Schoenberg’s twelve-tone opera Moses and Aron with his friend Betty Comden (Cohen) who recalled that:

Lenny told me that he had heard it only once before and was not sure how he felt about it, that it might be rough going, and we might want to wander out at some point. We sat there totally mesmerized and deeply moved. The prologue was a brief re-enactment of Kristallnacht with Jews hunted and cemeteries and synagogues defiled and destroyed. Onstage through the whole opera there was the menorah, overturned and broken, lying on its side. During the Golden Calf scene, they ingeniously used the arms of the candelabra to construct the golden horn of the idol. At the end Lenny turned to me and, visibly shaken, said that that was the opera he wished he had written.[22]

Throughout his life Bernstein’s Jewish identity remained incredibly strong: he repeatedly composed music on Jewish themes and in later years referred to himself as a “rabbi,” a teacher with a penchant to pass on scholarly learning, wisdom and lore to orchestral musicians. Bernstein adopted an Old Testament prophetic voice for much of his music, including his first symphony, Jeremiah, and his third, Kaddish. Music writer David Denby noted Bernstein’s fondness for using his symphonies as sanctimonious vehicles for ethnic and political propaganda:

In his symphonies, a natural lyrical impulse got overtaken by the hectoring political stances that had surrounded him as a young man. Bernstein was influenced first by the popular-front attitudes of the thirties and later by resistance to McCarthyism and the struggles against racism and anti-Semitism, all of which imbued liberalism with a high ethical fervor. The Holocaust and the birth of Israel extended these emotions into a mood of redemptive anger. He was a liberal who took things personally, and he confused “speaking out” with politics. Unfortunately, he began to confuse it with art, too.[23]

While West Side Story has retained its popularity with audiences, Bernstein’s “serious” compositions for the concert hall have, except for his overture to Candide (and notwithstanding a recent resurgence to mark the Bernstein centenary), fallen out of the classical repertory. Bernstein’s “serious” works were criticized during his lifetime for self-consciously striving for “profundity” while only achieving “grandiose gesture.” One critic scathingly observed that:

The serious music is a barrage of heartfelt emotions, the tortured, longwinded, richly orchestrated ramblings of one man’s public contact with the angst of life, the power of nature, the sorrow of death and pain. All is cast in vicarious musical language on the scale of Beethoven, Mahler and Shostakovich. The sentiment is sincere but commonplace. The art is secondhand. Bernstein’s serious music, at its best, is reminiscent of an exuberant adolescent who, lacking confidence in himself, uses impressive mannerisms, clichés and gestures to pour out his heart.[24]

Radical chic

For all his leftwing activist pretentions, Bernstein lived in grandeur in Manhattan and Connecticut, waited on by an army of liveried servants. He was famously the subject of a scathing article by Tom Wolfe in the New York Magazine in June 1970 which focused on his relationship with the Black Panthers. When, in 1969, twenty-one Panthers were charged with plotting to kill policemen, bomb police stations, department stores and railroad facilities, Bernstein’s wife Felicia organized a legal-defense fundraiser to be held at their Park Avenue apartment. Wolfe attended the event incognito.

Five months later Tom Wolfe’s 25,000-word article “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s” was published which portrayed the evening as a ham-fisted attempt to appear fashionably leftist. It made the event and Wolfe’s catchphrase world-famous and the Bernsteins the object of mockery and derision. Bernstein was even booed by his normally adoring Jewish subscribers at the Philharmonic who were horrified he seemed cozy with a group whose members had made statements in support of the Palestinians. When organized Jewry got wind of the Panthers’ anti-Zionist position, the Jewish Defense League picketed Bernstein’s apartment.

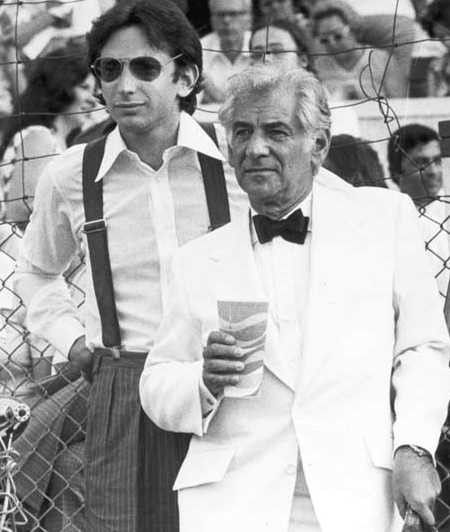

Leonard and Felicia Bernstein with Black Panther representative Donald Cox

Despite Bernstein’s ostensible support for the Black Panthers and advocacy for Black musicians, in his tenure as chief conductor and artistic director of the New York Philharmonic from 1958 to 1969 he hired only one African-American musician, the violinist Sanford Allen in 1962.

President Richard Nixon was advised to avoid attending the premiere of Bernstein’s “Mass” on September 7, 1971, a work that contained coded anti-Nixon messages in its Latin text. The White House tapes reveal Nixon later received reports of the “absolutely sickening” events that transpired at the premiere including “Bernstein’s tearful response to the ovation, his embrace of members of the cast, the kisses he bestowed on the men.” Nixon notes Bernstein’s support for the Black Panthers and expresses revulsion at news that Bernstein “is kissing people on the mouth, including the big black guy.” According to Nixon, “Bernstein was the personification of the complete decadence of the American upper-class intellectual elite” and a “son of a bitch.”

French kissing the world

In 1974 Bernstein’s wife Felicia was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent a double mastectomy. This marked the “beginning of a painful era for the entire family, marked by an erosion in Bernstein’s sense of discretion about his relationships with men.”[25] Bernstein’s “slow creep toward overt gayness” in middle age was abetted by his manager Harry Kraut, who “threw attractive young men in his path.” On one occasion Bernstein was having sex with a twenty-year-old man in the hallway of his Manhattan apartment while his wife was sitting in the living room. When he met the young Tom Cothran in 1973, he allowed his wife to catch them in bed together. Felicia “detested” Cothran and threatened to “make a public scandal” and New York Society was indeed shocked when Bernstein moved out of his marital home and into an apartment on Central Park South with Cothran. Felicia, distraught at Bernstein’s betrayal, one night “pointed her finger across the table at him and with her biggest scariest actress voice laid a curse on him: ‘You’re going to die a lonely, bitter old queen.’”

The following year when Felicia was diagnosed with lung cancer Bernstein broke up with Cothran and Mr. and Mrs. Bernstein were reconciled. After Felicia’s death a year later, Bernstein “gave free reign to his addiction to alcohol and drugs, and engaged in openly crude homosexual activities.” His wife’s death deprived him of any calming influence and his “intense physicality and flamboyance … became a beast unleashed.” He now felt free to lead an openly homosexual lifestyle and was “frequently surrounded by groups of adoring young men.” Bernstein’s daughter recalls her father starting to act “exuberantly gay and calling everyone darling.” He loved to shock and was notorious for greeting backstage guests wearing nothing but a jockstrap or red bikini brief. Shawn observes that:

Without the rudder of his marriage he became more extreme and more insecure. Even an admirer such as composer Ned Rorem was taken aback by his friend’s self-absorption and need to be reassured and flattered during this time. In public, Bernstein’s physical demonstrativeness – which was not always entirely consensual – was sometimes too much of a good thing. As one old friend put it, “He had his tongue down everyone’s throat – men and women. He wanted to French kiss the world.” Copland, Blitzstein, and Laurents had cautioned him about the destructive and drug-like properties of fame. Writer and composer, Paul Bowles, a friend since the 1930s, told a biographer that fame had made Leonard “smarmy and false.”[26]

Pianist William Huckaby, after performing at a White House recital in the late seventies, was talking with President Carter when he “felt these hands clamped on my shoulders. I was whirled around and engaged in a deep kiss of the French variety and Bernstein was saying, ‘I haven’t heard such virile piano playing for fifteen years. It was magnificent.’ President Carter watched all this with his mouth open and then walked away.” During his last decade, Bernstein was “surrounded by an entourage of beautiful boys, each one as intoxicated and obnoxious as his patron.” Over-indulged by this fawning entourage, Bernstein (who used the car license plate ‘MAESTRO 1’) behaved as he liked. Bernstein’s personal assistant documented Bernstein’s habit of patting his assistants’ crotches.

In her 2018 book Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein, Bernstein’s daughter Jamie revealed that her father even liked to put his tongue in her mouth as he kissed her. It was designed, she says, to find out “how accommodating they were, how sexy they were, how much impact he was making. My dismay was tempered by knowing he did it to so many others.” She was, nevertheless, confused by her highly-sexed father’s mix of “tenderness and raunchiness.” She felt a “vaguely unclear boundary” about their relationship when she was a teenager, recalling that “It was hard not to feel my father’s sexuality … everybody felt it. Tricky stuff for a daughter.”

The Bernstein family had to put up with the man they called “LB” throwing lit cigarettes at them across the dinner table, calling them “fuckface,” and dumping them in awkward situations. An insomniac who worked mostly at night, Bernstein drank heavily and became addicted to prescription painkillers, “keeping a vast, multi-colored collection of them in a large black leather toiletry case.” He daughter recalls that while her father wore tails to work, he was a slob at home who had a signature smell of “cigarette smoke and flatulence, which would commence at the breakfast table.”

Bernstein with young Jewish homosexual conductor Michael Tilson Thomas in the 1970s

Late in life, Bernstein became ever more focused on teaching and mentoring young people, including the young Jewish homosexual conductor Michael Tilson Thomas – today the music director of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra. His late compositions, including A Quiet Place, a two-hour opera built upon his earlier work Trouble in Tahiti, were deemed failures. One reviewer described the plot of A Quiet Place as a “gloomy soap opera about uninteresting characters, with an emphasis on incest and homosexuality.” Critic Donal Henahan wrote, “To call the result a pretentious failure is putting it kindly.”[27]

Bernstein died aged 72 five days after announcing his retirement from conducting on October 9, 1990. His death was caused by a heart attack brought on by mesothelioma, his body ravaged by alcohol, amphetamines and cigarettes. His family deny he was HIV positive at the time of his death.

Conclusion

For the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia, Bernstein’s lasting cultural legacy, aside from his lifelong commitment to Jewish causes, resides in his “pushing boundaries, breaking down walls, bucking tradition.” Bernstein’s Jewish background and radical political outlook are “absolutely essential to understanding many of his key works.” Careful examination of the subtexts of his works, including West Side Story, reveals “more subversive content” than many have chosen to see. In such works and in his political activism, Bernstein “challenged norms and tried to change the world order.” Alex Ross, the Jewish music critic for The New Yorker, argues that Bernstein’s political stance “once mocked and dismissed, looks different in today’s political climate.”

That Bernstein was a pathbreaker for the Cultural Marxism that now dominates Western culture — and is lauded by Jews as such — is revealed by the fact that two hagiographic Hollywood movies about him are currently in production: The American which is being developed by the Jewish actor Jake Gyllenhaal, and Bernstein which is set to be directed by and star Bradley Cooper. Gyllenhaal, in a statement, said “Like many people, Leonard Bernstein found his way into my life and heart through West Side Story when I was a kid. But as I got older and started to learn about the scope of his work, I began to understand the extent of his unparalleled contribution and the debt of gratitude modern American culture owes him.”

Bernstein’s contribution to modern American culture: promoting multi-racialism, black grievance politics, feminism, and sexual license were, it hardly needs saying, entirely contrary to the group evolutionary interests of White Americans.

[1] Norman Lebrecht, Why Mahler? How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed the World (London: Faber and Faber, 2010), 225.

[2] Adorno, T., “Centenary Address, Vienna 1960,” in Quasi una fantasia — Essays on Modern Music, trans. by Rodney Livingstone (London & New York: Verso, 1963), 88.

[3] Leonard Bernstein, The Unanswered Question: Six Talks at Harvard (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1990), 313.

[4] Allen Shawn, Leonard Bernstein: An American Musician (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 175.

[5] Ibid., 174.

[6] Ibid., 174-75.

[7] Ibid., 179.

[8] Ibid., 38.

[9] Ibid., 42.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Leonard Bernstein, “Mahler: His Time Has Come,” High Fidelity, April 1967.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Barry Seldes, Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2009), 195.

[14] Rick Schultz, “The Wagner Problem,” Jewish Journal, April 7, 2010. https://jewishjournal.com/culture/music/78198/

[16] Quoted in Liam Hoare, “Leonard Bernstein’s Tense, Torn Love Affair With Vienna,” Tablet, October 2, 2018. https://www.tabletmag.com/scroll/273026/leonard-bernsteins-tense-torn-love-affair-with-vienna

[17] Paul R. Laird, Leonard Bernstein (London: Reaktion Books, 2018), 238.

[18] Caroline Evensen Lazo, Leonard Bernstein: In Love With Music (Minneapolis MN: Twenty First Century Books, 2002), 97.

[19] Humphrey Burton, Leonard Bernstein (London: Faber & Faber, 2017), 442.

[20] Museum Judenplatz, “Leonard Bernstein: A New Yorker in Vienna,” Jewish Museum Vienna. http://www.jmw.at/en/exhibitions/leonard-bernstein-new-yorker-vienna

[21] Ibid.

[22] Shawn, Leonard Bernstein: An American Musician, 262.

[23] Seldes, Leonard Bernstein: The Political Life of an American Musician, 170.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid., 234.

[26] Ibid., 243.

[27] Ibid., 250.

Comments are closed.