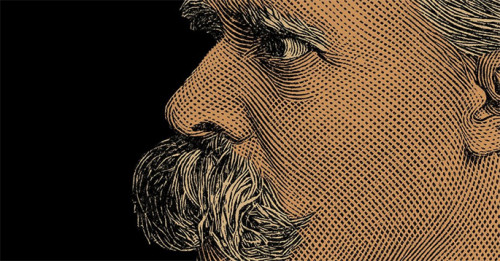

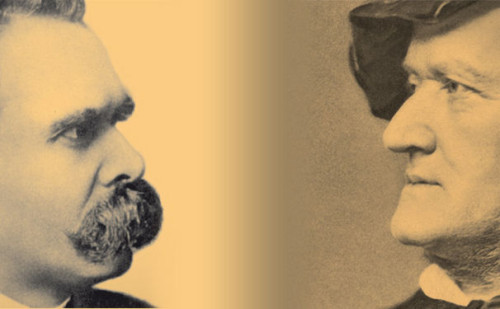

‘Wagner himself asserts about Nietzsche that a flower could have come from this bulb. Now only the bulb remains, really a loathsome thing.’

Cosima Wagner, 1878.

Friedrich Nietzsche’s puzzling stance on Jews and Judaism has perplexed me for the better part of a decade, so I was intrigued and optimistic about Princeton University Press’s 2015 publication of Robert Holub’s Nietzsche’s Jewish Problem: Between Anti-Semitism and Anti-Judaism. Broadly speaking, I’m sympathetic to certain elements of Nietzsche’s philosophy, particularly its rejection of equality and the concept of the ‘will to power.’ However, I can’t say I ever came close to describing myself as a ‘Nietzschean’ in the same way that the late Jonathan Bowden was fond of doing. One of the reasons for my hesitation in claiming affinity with Nietzsche’s worldview was that I couldn’t escape the impression that its nihilism was often destructive ‘for the sake of it,’ a quality that has endeared it to the Left, past and present. Then there was Nietzsche’s, to my mind unforgivable, habit of lauding the Hebrew over the German. More importantly though, I couldn’t perceive any true coherence or solidity in Nietzsche’s writing beyond his celebrated aphorisms. Taken as a whole, the philosophy of Nietzsche was apt to strike me as too intentionally fluid; too deliberately open to interpretation. Nowhere was this non-committal stance more apparent than in Nietzsche’s sparse, vague, contradictory and often quite opportunistic references to Jews and Judaism.

As one might expect of a philosopher as enigmatic as Nietzsche, his work has been approached awkwardly and suspiciously by scholars and ideologues alike. His attitudes towards Jews, in particular, have been debated, discussed and fought over from the very beginning of his public career. Nowhere, and at no time, was a consensus ever reached. During the Third Reich he was both ‘recruited for the cause’ by some, and rejected outright by others. His foundational place in the National Socialist philosophical canon was thus never assured, primarily because of his nihilism, his hostility towards Nationalism, and his ambivalence regarding Jews. Confusion still reigns. Modern scholarship has been divided between those who condemn Nietzsche outright as a ‘racist’ reactionary and a proto-Fascist, and those who highlight his vocal opposition to political anti-Semitism as thus seek his social exoneration and academic rehabilitation. As noted above, elements of Nietzsche remain strongly attractive to the Left. Therefore, where total exoneration of anti-Semitism has been found difficult, blame for ‘corrupting’ Nietzsche and shaping him as an ‘anti-Semite’ has been attributed variously to his one-time guru, Richard Wagner, or his sister Elisabeth, who married Bernhard Förster, perhaps the leading figure in nineteenth-century political anti-Semitism. The result of these battles has not been a clarification of the historical record, but an ever-thickening web of biased interpretations, white-washing, and pseudo-history. Read more

among many Evangelical Christians, but also

among many Evangelical Christians, but also