Igor Shafarevich and the Jews

One way to become an unwitting dissident is to assume that the truth will set everyone free.

Igor Shafarevich, in his 1989 essay “Russophobia” (my review here), spoke the truth about the overwhelmingly negative impact the Jewish Left has had on Russia, and he received merciless defamation from the Jewish Left in return. Much of this abuse came from the mostly Jewish “Third Wave” of Russian émigrés who were known for their undue and quite racist insults of Russians during the 1970s. (Russians being either brutal, slavish, or messianic were the most prominent stereotypes.)

The essay uncovered the Jewish complicity in the October Revolution and its bloody aftermath as well as tied contemporaneous Jewish revolutionary spirit to the ancient Judaic concept of being “the Chosen People.” For Shafarevich, left-wing, revolutionary Jews made up the core of what historian Augustin Cochin referred to as “the Lesser People,” an elite minority spiritually and ideologically at odds with the established order, as represented by the majority, or “Greater People.” Cochin was describing the French Revolution, and Shafarevich deftly borrowed his terminology to portray the much greater Russian catastrophe of 1917.

Beyond any commentary on Jews, Shafarevich intended with “Russophobia” to promote healthy self-esteem among Russians (based on a realistic understanding of history, of course). He also wished to assess in what ways Western-styled democracy and technology might help or not help Russia. Yes, of primary interest was what’s good for Russia and Russians, but there is nothing in “Russophobia” which denigrates the national aspirations or human rights of other peoples. Shafarevich had previously made this point in his essay “Separation or Reconciliation?” which appeared in the 1974 collection From Under the Rubble. This essay echoes Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “Repentance and Self-Limitation in the Life of Nations” (which appeared in the same volume) and demonstrated that nationalism, even intense, passionate nationalism, does not necessarily result in chauvinism. When defending “Russophobia,” Shafarevich himself stated that “it is much more wholesome to discuss openly all sides of all national relations.”

But this point got lost entirely among his critic-enemies, who couldn’t see past the Jew thing. As Krista Berglund notes in her 2012 volume, The Vexing Case of Igor Shafarevich, a Russian Political Thinker, Shafarevich had no intention of libeling Jews. He wished only to

treat Jews on equal terms with other peoples, without the demand to apply to the Jews any special standards. . . . The major reason for him to raise the Jewish issue in Russian history was again his conviction that when discussion of historical tragedies is suppressed and when there are unhealthy taboos, this tends to breed frustration, friction, artificial antagonisms and irrationality. One such suppressed issue was the disproportional Jewish contribution to the Russian Revolution. When raising it, Shafarevich’s intention was to systematically separate myths and irrational notions from historical facts and to contribute to the normalisation and amelioration of Russo-Jewish relations.

In other words, the truth will set us free and reduce tensions between peoples. Unfortunately, this didn’t turn out to be the case, despite Shafarevich’s good intentions. Speaking the truth about Jews—which was merely one of several things Shafarevich accomplished in “Russophobia”— enflamed not only the Jews he referred to in his essay but much of the Jewish intellectual class worldwide. And they used their considerable influence quite spitefully to ruin him. In my previous article on “Russophobia,” I described some of the backlash, but in truth it was far worse than that.

As one would expect, there were the hysterical ad hominems and overreactions, none of which was at all substantive. Philologist Efim Etkind called “Russophobia” as “a call for pogroms” and likened Shafarevich to “Stalinist pogrom-makers.” He also wailed that the ideas in “Russophobia” would ultimately result “in the poisonous smoke of Treblinka’s crematoria.” Art historian Igor Golomshtok made Mein Kampf comparisons and accused Shafarevich of propagating the idea of “Jewry as the embodiment of universal evil.” Astonishingly, lit critic Grigory Pomerants (whom Shafarevich names in his essay) hadn’t even read “Russophobia” when he opined that its author’s world is only black and white, and then reiterated his claim that Russia is a “land of slaves”—thereby refuting himself in the eyes of those who had actually read the essay.

In a nearly perfect act of projection, Valentin Liubarsky, another Third Wave writer, claimed that “Shafarevich is concerned with the rationalisation of mass hysteria.” Writer Benedikt Sarnov made the expected comparisons to Hitler, Alfred Rosenberg, and Julius Streicher, and called for the KGB to investigate Shafarevich. He then darkly reminded his readers that Rosenberg and Streicher had died from hanging. Andrei Sinyavsky, a writer and gentile ally of the anti-Shafarevich movement, dubbed Russian russophobes as “Satan” and declared that “Russophobia” “fully coincides with the theories of German Nazism, from Hitler to Rosenberg.”

Shafarevich’s closeness with Solzhenitsyn could not save him from Jewish Solzhenitsyn defenders, such as Israeli émigré writer Dora Shturman, who lamented how “Russophobia” engendered in her the “horror – no, not of simple-minded pogrom, but of a Holocaust; of ruthless, inhuman abandonment which is a precondition for destruction.” Jewish writer and émigré Boris Paramonov responded provocatively with an article entitled “Shit. An Attempt at Public Psychoanalysis.” In it, he insinuated that because Shafarevich is supposedly part of a native soil movement in Russia, he is literally obsessed with feces. He also risibly claimed that in “Russophobia” “Shafarevich’s subconsciousness beating of children is taking place.” A paradigmatic example of psychoanalytic fantasy unmoored from any need for empirical justification.

Paramonov’s vindictive psychoanalysis becomes more sinister when considering that, as a human rights activist during the 1970s, Shafarevich strenuously protested the Soviet practice of punitive psychiatry. When it became less acceptable to ship political prisoners to gulags (thanks, in large part, to the worldwide success of Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago), Soviet authorities pivoted to insane asylums, which in many cases amounted to the same thing.

Berglund adroitly dismisses Paramonov when stating that he

resorted to the cheapest and flimsiest kind of below-the-belt pseudo-psychoanalysis with the intention of establishing Shafarevich as a pitifully traumatised old man whose ideas do not deserve serious consideration (but, apparently, need necessarily to be rebuffed time after time).

This lunacy made its way to Western journals as well. In my previous essay, I mentioned how Walter Laqueur, Josephine Woll, and others overreacted to “Russophobia.” Berglund gives us much, much more.

Newsweek, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, and The New Republic all labeled Shafarevich an anti-Semite. Liah Greenfield of Harvard claimed that in terms of anti-Jewish polemics “Russophobia” excelled even Medieval anti-Semitism. David Remnick and Alan Berger both fueled false speculations of impending pogroms in Russia as a result of this essay.

It should be noted that Jonathan Steele of The Guardian wrote the following in 1990 about these pogrom rumors:

[S]ome sources have suggested that the rumours may have been started by extremist Jewish groups which are unhappy with the US Congress’s recent decision to deny Soviet Jews refugee status and treat them as economic migrants. Creating a climate of fear could change the US Congress’s mind.

In the same year, our old friend Joe Sobran summed up the Western response to “Russophobia” thusly:

None of Shafarevich’s fuming denouncers has produced a single quotation from him advocating any sort of injury to Jews. . . .Yes, in spite of his courage as an advocate of human rights, he is being lumped together with the sort of hooligans who favour beating Jews in the street.

These “hooligans” Sobran mentioned most likely refers to the Pamyat movement in Russia (albeit unjustly). This was a pro-Russian activist organization which took advantage of Glasnost to stage patriotic demonstrations. Aside from promoting Russian ethnic identity, speaking out against alcoholism, and “lobbying against the rechanneling of the great Siberian rivers,” Pamyat was also fairly hostile to Jewish interests, according to Berglund. They promoted anti-Zionism and propagated the Judeo-Masonic conspiracy theories expressed in The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Ironically, the Soviets tolerated Pamyat when it was attempting to dampen the mood on Israel, but as soon as people in Pamyat began speaking about the disproportionately Jewish nature of early Bolshevism—which apparently hit a little too close to the Kremlin—the Soviets cracked down on the nationalist organization.

At the time, Pamyat was suffering from much internal strife and had never been a major force in Russian politics (historian John Klier describes the organization as “fissiparious”). When asked about it, Shafarevich correctly downplayed its significance. Indeed, Shafarevich had never had any personal involvement in Pamyat. But because members of Pamyat naturally connected with “Russophobia” and propagated it through Samizdat (without his knowing, of course), Shafarevich’s enemies falsely condemned him for being linked to this anti-Semitic, nationalist organization. It was guilt by association when there really wasn’t any association—and probably not a whole lot of guilt, either. In fact, a Pamyat leader named Dmitry Vasilev had condemned Shafarevich for his “purely Jewish point of view.”

It seems that the Jews in academia (both Western and Soviet) needed Pamyat, and manufactured much of its infamous reputation. Berglund cites a 1992 study which demonstrates the general lack of anti-Jewish extremism among members of Pamyat as well as a somewhat shaky understanding of “Russophobia” to begin with. She also quotes Klier’s late-nineties interview with a Pamyat propaganda distributer who complained that “Foreigners are more interested in what we say than our own people.”

None of the predictions of Russian pogroms actually played out—even during the economic misery of the 1990s when one would presume an easily identifiable scapegoat would be just the thing to ignite mass violence. In spite of this peace and restraint on the part of these brutish, messianic Russians, influential Jews needed a villain, a reconstructed Black Hundreds Frankenstein of fascism which they could point to and say, “There! There is Russian anti-Semitism in the flesh!”

Why? To pressure Soviet authorities to allow Soviet Jews to emigrate and to pressure Western governments to give these Jews refugee status. As a result, many of these émigrés wound up in Western Europe or the United States instead of Israel, despite their purported persecution as Jews. And a third reason: to destroy the most prominent White gentile in the world at the time who was telling the truth about Jews—Igor Shafarevich.

“Russophobia” caused a great stir in science and mathematics circles as well, mainly because Shafarevich is considered one of the twentieth century’s most prominent mathematicians. From his Wikipedia page we learn that:

Shafarevich made fundamental contributions to several parts of mathematics including algebraic number theory, algebraic geometry and arithmetic algebraic geometry. In algebraic number theory the Shafarevich–Weil theorem extends the commutative reciprocity map to the case of Galois groups which are extensions of abelian groups by finite groups. Shafarevich was the first to give a completely self-contained formula for the pairing which coincides with the wild Hilbert symbol on local fields, thus initiating an important branch of the study of explicit formulas in number theory.

Not even such a resume could protect Shafarevich from the coming indignities. His nomination for an honorary degree at Cambridge was instantly withdrawn. The National Academy of Sciences of the United States (NAS) urged him to renounce his membership. Numerous mathematics and science societies applauded this move, including the Union of Council for Soviet Jews, whose leaders declared that Shafarevich is “inimical to the fragile causes of human rights.” This, of course, maligned an unimpeachable human rights activist who stood up to the Soviet system, side-by-side with Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov, on the Moscow Dissidents’ Human Rights Committee in the early 1970s.

After this came suspicions and utterly unfounded accusations of anti-Jewish discrimination. Even some of Shafarevich’s former Jewish students defended him on this count—although not for “Russophobia.” Indeed, as an academic who was responsible for launching or aiding numerous careers (including many Jewish ones) his reputation had been impeccable. It was only after “Russophobia’s” publication when it all was conveniently called into question.

A condemnatory letter initiated by mathematician Laurent Swartz garnered over 200 signatures. Another one with over 450 appeared in a Russian periodical, to which Shafarevich made this dry yet cutting response:

[T]he people who signed the letter and whom I knew 15 or 20 years ago as Soviet mathematicians . . . witnessed the deportation of Solzheni[tsyn], exile of Sakharov, persecution of religion, detention of sane persons in psychiatric hospitals for political reasons. We [did not hear] their protests against it then. Do they really believe that my paper is more dangerous?

By summer 1991, according to Berglund, “Shafarevich’s reputation as a notorious anti-Semite had been cemented virtually in all circles of self-respecting liberals in both the East and the West.” She goes on to name over 30 people who had heaped undue scorn upon Shafarevich.

Berglund makes The Vexing Case quite unique when she analyses “Russophobia” alongside its criticisms to demonstrate, as if in a court of law, how Shafarevich was not only not anti-Semitic, but was also in fact quite reasonable, evenhanded, and most likely correct. She also shoots down every single one of her subject’s critics. In one or two cases, Shafarevich faced reasonable—if perhaps flawed—reproaches, which Berglund appropriately dispenses with. All the others she reveals as shoddy and irresponsible at best or deceitful and malicious at worst. It must be said that most of the villains here were Jews. It must also be said that, at least in Berglund’s comprehensive analysis from over two decades after the fact—and with Shafarevich still living to provide commentary—none of these villains had ever apologized or faced a comeuppance.

At times Berglund does wade into the weeds when exploring all the argumentation needed to exonerate Shafarevich. For example, she includes long discussions of Israel Shahak’s Jewish History, Jewish Religion, Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century, and many other works and topics in order to provide greater context for this important and potentially explosive subject. The book is nearly 500 pages (with more than a quarter of it dedicated “Russophobia” or anti-Semitism), and sometimes feels like it. This is not a biography; it is a vindication of a man who in a perfect world would not need vindication at all.

Instead, Igor Shafarevich told the truth and became a dissident once again, and in some ways suffered more hyperbolic abuse than when he was a Soviet citizen. Berglund suggests that Shafarevich, in his frank and fair-minded appraisal of Jews, actually suppressed anti-Semitism in his native Russia.

While many vociferous commentators have alleged that in the person of Shafarevich Russian anti-Semites had got a prominent frontman, there are actually strong hints that he managed to effectively “neutralise” the message of many of those obsessed with Jews among his Russian contemporaries.

Of course, this is nice. But, in turn, did “Russophobia” also suppress the real-life russophobia that Shafarevich so meticulously described? Did it neutralize the message of many of those obsessed with Russians (or Whites in general) among his Jewish contemporaries? Jewish neocons and their incessant anti-Russia posturing during the current war in Ukraine may give us a clue. But sadly, this is a question Berglund fails to ask, and so in The Vexing Case of Igor Shafarevich, goes unanswered.

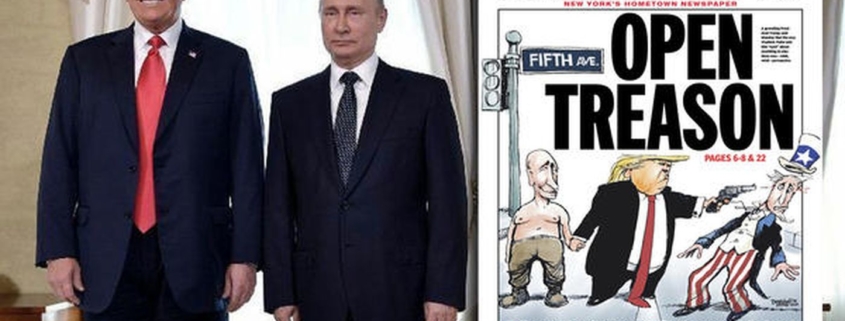

The Trump-Putin summit in Helsinki has resulted in the greatest outpouring of TrumpHate to date. Truly stunning. The #NeverTrumpers (basically neocons) now joined at the hip with the liberal/left have finally found the issue they think they can win on. Sure, the image of children being taken from their parents was effective with the people who already hated Trump. But this

The Trump-Putin summit in Helsinki has resulted in the greatest outpouring of TrumpHate to date. Truly stunning. The #NeverTrumpers (basically neocons) now joined at the hip with the liberal/left have finally found the issue they think they can win on. Sure, the image of children being taken from their parents was effective with the people who already hated Trump. But this