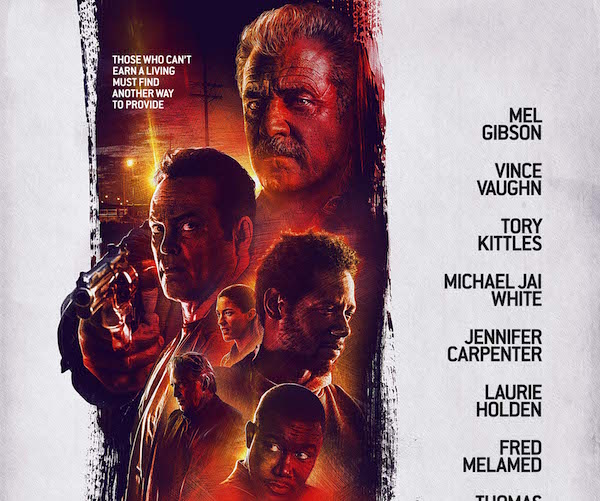

Dragged Across Concrete (2019) and the Art of Cinematic Trolling

The author writes at Logical Meme and @Logicalmeme.

9125 words

Since the 1960s, there have been sporadic reactions in film against emergent liberal hegemonies in culture. In the early 1970s, when the social changes borne of the countercultural 1960s were, in very short order, becoming the mainstream culture and translating into the disastrous social policies of that era, there were occasional sympathetic depictions from Hollywood which channeled White discontent and a growing White male anxiety — for example, Dirty Harry (1971), The French Connection (1971), Death Wish (1974), and Taxi Driver (1976) — but by the 1990s, articulation of this anxiety (which, as a sociological phenomenon became hardened, not softened, through decades of collective experience) was largely expressed, ironically, through unsympathetically depicted characters — for example, Falling Down (1993) and American History X (1998)[1].

Since this time, the Hollywood filmmaking pipeline has become thematically constricted by a radical surge of political correctness and leftwing, agenda-driven depictions of race and racial conflict. Unspoken rules ensure that any film dealing with race ultimately settles on the side of predictable, leftwing, social justice platitudes. (Various Oscar-winning films of recent years attest to this.) As such, when it comes to subjects such as racial conflict, the effects of mass immigration, or the plight of Whites in America, there is simply no diversity of opinion coming out of Tinseltown. Creatively, this has led to a metastasizing sameness, a bland and boring creative funk, to mainstream films that touch upon such subjects.

In terms of the sociology of filmmaking, the significance of Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ (2004) was to demonstrate — in stark, jaw-dropping, financial terms — the profound imbalance between the demand for ‘conservative’ films and the sparse supply of such films coming out of a leftwing, Jewish-dominated Hollywood system. Passion was independently produced and distributed by Gibson’s Icon Productions, going on to earn over $600 million worldwide, and currently stands as the highest-grossing R-rated movie in history. (The film also confronted strong rebuke and charges of anti-Semitism from prominent Jewish individuals and organizations.) Gibson’s next film Apocalypto (2006), also produced by Icon Productions, depicted violent, genocidal, tribal conflict in sixteenth century Mexico, and alluded to the eclipse and decline of Mayan civilization, emphasized in the film’s penultimate scene of Spanish Christian conquistadors arriving by ship to the jungle’s coast, with the indigenous locals looking on in awe. (Not surprisingly, Apocalypto was castigated in some quarters for harboring racist and colonialist apologetics.) Read more