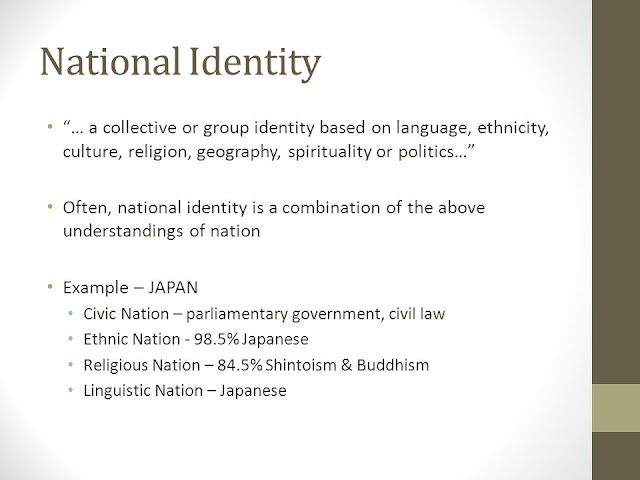

西洋文化をユニークにしたものは何か (“What Makes Western Culture Unique”)

What Makes Western Culture Unique? 翻訳

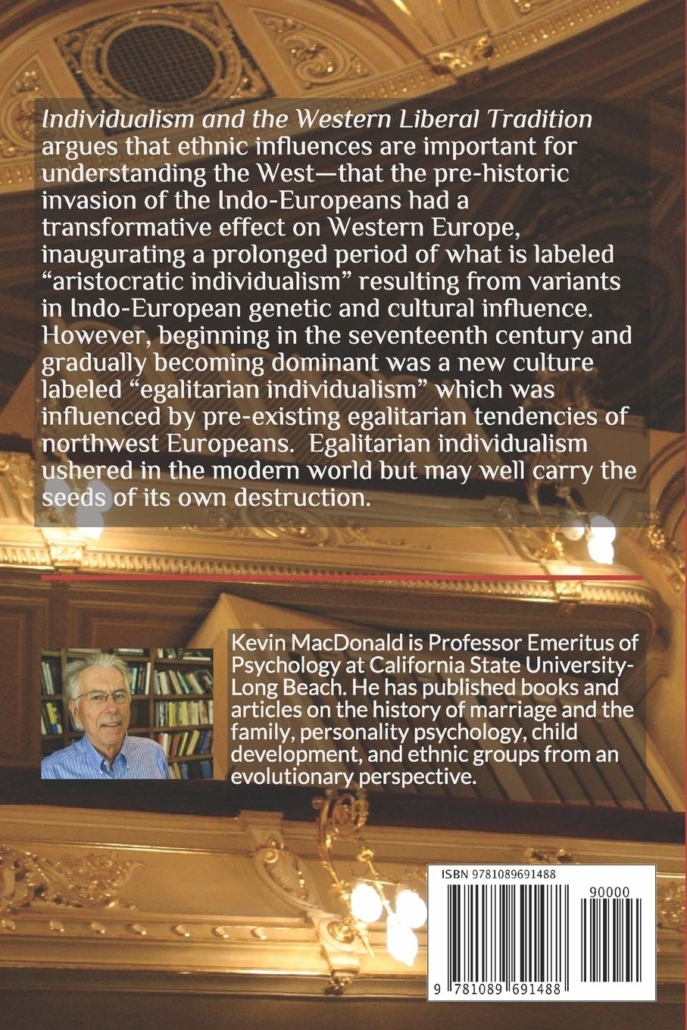

Kevin MacDonald

西洋文化をユニークにしたものは何か

原文:http://www.kevinmacdonald.net/west-toq.htm

一般に、文化のユニークさは自然由来か教育由来かのどちらかである。これは昔から変わらない二項対立である。

しかし我々は現在これらの問題について昔よりもより良く扱える立場にあり、そして自然由来説と教育由来説のどちらも重要であることを説明しようと思う。

西洋文化は、どのような生物学的/進化論的理論でも予測がつかないほどの独特の文化的変貌を経験してきたが、同時にユニークな進化の歴史もあった。

西洋文化は、世界の他の文明や文化を築いた人々とは遺伝的に異なった人々によって構築された。

西洋文化が他の伝統的文明と比較してユニークな文化的プロファイルを持つことを以下で論じる。

1. カトリック教会とキリスト教

2. 一夫一妻制の傾向

3. 核家族が基本のシンプルな家族構造の傾向

4. 結婚が両性の合意に基づいており、相互の愛情を基本にする傾向が強い

5. 拡大血縁(extended kinship relationships)とその互恵関係の重視を避け、エスノセントリズムが比較的弱い

6. 個人主義へ向かう傾向。国家に対する個人の権利、代議制政府、道徳の普遍主義化、自然科学へ向かう傾向

私のバックグラウンドは進化生物学の分野であり、性の進化論を扱った時に最初に感じた疑問の一つは、「なぜ西洋文化は一夫一妻制なのか?」だった。

性の進化論は非常にシンプルである。女性は生殖に多大な投資が必要である。妊娠、授乳、そして育児は大抵膨大な時間を要求する。

その結果、女性の生殖には厳しい制約がある。最高の条件を用意してもらっても、最大でも20人程度の子どもしか育てようがない。

しかし、男性にとっては生殖のコストは低い。結果として、男性は複数の配偶者から恩恵を得ることも可能で、富と力を持つ男性はそれを活用して可能な限り多くの配偶者を確保することも期待できる。

要約すれば、富と力を持つ男性による集中的な一夫多妻制は男性にとって最も適切な戦略であり、個々人の男性の生殖の成功にとって最も適切な振る舞いである。

この理論は十分に支持されている。世界中の伝統的な社会では、富と生殖活動の成功との間に強い関連性がある。裕福で力のある男性は非常の多数の女性をコントロールできる。

中国、インド、イスラム社会、新世界文明、古代エジプト、古代イスラエル等の世界中の全ての伝統的文明のエリート男性は、大抵数百人から数千人にもなる側室を持っていた。

サブサハラ・アフリカでは女性は一般的に男性の扶養なしで子どもを育てることができるので、結果として、男性はできるだけ多くの女性をコントロールするために競争する低レベルの一夫多妻制になった。

これらいずれの社会においても、これらの関係から産まれた子どもは合法的だった。彼らは財産を相続することができ、世間から蔑まれることもなかった。

中国の皇帝には数千人の側室がおり、モロッコのスルタンは888人の子どもを持つことでギネスブックに登録されている。

勿論、一夫一妻制が標準の社会は他にもある。生態学的に課せられた一夫一妻制と社会的に課せられた一夫一妻制とを区別することが一般的である。

一般に、生態学的に課せられた一夫一妻制は、砂漠や寒冷地等の非常に過酷な生態的条件への適応を強いられた社会で見られる。

このような過酷な条件下では、各男性の投資は一人の女性の子供達に向かわざるを得ず、更に多くの女性をコントロールすることは不可能である。

基本的考え方としては、過酷な条件下では女性は一人で子どもを育てることが不可能で、男性からの手助けが必要である。

このような条件が、進化論的に意味を成すほど長期間続いた場合には、人口は一夫一妻制に向かう強い傾向を発達させると予想できる。

実際に、一夫一妻制の傾向が強くなりすぎると、生態学的条件の変化に直面した場合でも一夫一妻制に向かう心理的・文化的傾向へとつながることが予想できる。

私はヨーロッパ人の進化で正にこのことが起きたのだと提案しており、以下で詳述する。

Richard Alexanderは”socially imposed monogamy” (SIM)[社会的に課せられた一夫一妻制]という用語で、過酷な生態的条件なしの一夫一妻制を定義した。

過酷な条件とは男性が直接子供を養育せざるを得ない条件のことを指す。それ以外の状況では、男性は自分にできる限り多数の妻を持つために競争すると予想でき、一般的にもそうなる。

西洋のユニークさの最初の例

世界の他の経済的先進地域の文化は、成功した男性による一夫多妻制が特徴であるのに対して、西洋社会には古代ギリシャ・ローマから現代にいたるまで一夫一妻制の強い傾向がある。

古代ローマには、一夫一妻制を志向する様々な政治制度や思想の背景があった。

ローマで社会的に課せられた一夫一妻制の起源は歴史から忘れられているが、一夫一妻制を維持させるための幾つかのメカニズムが存在した。

一夫一妻制の外で生まれた子どもの法的地位を下げる法律、離婚を妨げる習慣、不適合な性的行動に対してネガティブな社会意識、そして一夫一妻制が性的に正統だと定める宗教思想があった。

これらのメカニズムのバリエーションは西洋の歴史を通じて現代まで続いている。

共和制ローマの時代には、コンスルの任期制限、二人のコンスルを同時に存在させるなどで特定の貴族の一族が専制を敷けないようにする仕組みもあった。

下層市民の政治代表権についても、護民官を設置するなど徐々に法整備が進んだ。近親者の結婚を妨げる広範な法律も存在した。

これらの法律が親族集団内での富の集中を防ぎ、特定の貴族の一族の支配を防いだ。

ローマの一夫一妻制は完璧とは程遠かった。

特に帝政期には離婚が増加し、共和制初期の特徴だった一夫一妻制を性的に正統とする思想が衰退したことで、それまでの家族機能が全般的に崩壊した。

それでも法的には、少なくとも理論的には、ローマ文化は最後まで一夫一妻制だった。一夫多妻制は法律で認可されることは無く、一夫一妻制の外で生まれた子どもには相続権は無いままで、母親の社会的・法的地位を受け継ぐことになった。

カトリック教会はエリート男性に一夫一妻制を課そうとしたので、一夫一妻制を巡る争いは中世の重要な特徴となった。

カトリック教会は西洋文化のユニークな一面である。

13世紀に中国に訪れたマルコ・ポーロや1519年にアステカに到着したコルテスは、現地の世襲制貴族・神官・戦士・職人・農民から成る農業社会を観察し、彼ら自身の社会との多数の類似点に気づいた。

社会同士の間には圧倒的な収斂性があった。しかし彼らは、宗教組織が世俗組織より優れていると主張し、世俗エリートの生殖行動の抑制に成功しているような社会は西洋以外に見出せなかった。

また、Louis IX (St. Louis) のような、フランスを統治しながらも一人の妻と一緒に修行僧のような生活をし、聖地解放の十字軍に参加するような王は、西洋以外には見出せなかった。

一夫一妻制が法と慣習として根付いたローマ文明の相続人であったカトリック教会は、中世には勃興してきたヨーロッパ貴族に一夫一妻制を課すようになった。

確かに、中世初期のヨーロッパ貴族の一夫多妻制は、中国やイスラム諸国のハーレムと比べてかなり小規模であったが、それは中世初期のヨーロッパの経済状況が比較的未発達であったことも一因であろう。

なにしろ中国の皇帝は広大で人口の多い莫大な余剰経済生産を持つ国を持っていた。彼らは中世初期ヨーロッパの部族長より遥かに裕福で、その富と力ではるかに多くの女性を手に入れた。

とにかく、一夫多妻制はヨーロッパにも存在しており、中世には教会と貴族の紛争の種となった。

教会は「中世ヨーロッパで最も影響力が強く重要な政府機関」で、世俗的な貴族に対するこの権力の主要な一面が性と生殖の規制だった。

その結果、富裕層にも貧困層にも同じ性的規制が課せられた。

教会の目論見として「信徒の中でも特に最も有力な者に対し、教会の権威に服属して彼らの道徳、特に性道徳を監督させることを要求した。これにより、結婚を通して教会は貴族をコントロールできた。結婚と夫婦間の問題は全て教会に持ち込むことを強いられ、教会のみが解決できるとされていた。」

進化心理学の観点からこの時期の教会の行動を理解する試みは、この論文の範囲外である。

しかし、権力欲は人間の普遍的な欲求であるが、他の全ての人間の欲求と同様、それが必ずしも生殖の成功と関連する必要はないことに注意する必要がある。

同様に、人はセックスの欲求があるが、母なる自然がそのようにデザインしたにもかかわらず、セックスを沢山すれば必ずしも多くの子供を持つことに直結するとは限らない。

教会のユニークな特徴の一つとしては、教会が利他的であるというイメージ(及びその実態)がその人気を支えていた。

中世の教会は、女性をコントロールしたり生殖で高い成功を収めることに教会はあまり関心を持たないと人々に思わせるイメージ戦略に長けていた。

これは常にそうだったわけでは無い。中世の改革以前には、多くの司祭が妻や側室を持っていた。

Saint Bonifaceは742年にフランスの教会について以下のように書き、ローマ教皇に苦言を呈した。「いわゆる司祭補佐は、少年時代から放蕩、姦淫、あらゆる穢れに人生を浪費し、その悪評のままで司祭補佐になり、今やベッドに4、5人の側室を抱えたまま福音書を読む有り様である。」

にもかかわらず、聖職者の改革は本物だった。13世紀のイングランドの高位聖職者で妻や家庭を持った者はいなかったとされる。

この時代のイングランドでは下級聖職者の間でさえ妻帯者は例外的であり、この聖職者のモラルの高さは宗教改革の時代まで保たれた。

教会はこのように貞操と利他主義のイメージを人々に植え付けた。その権力と富は生殖の成功に向けられてはいなかった。

教会の真の生殖利他主義は、極めて禁欲的な修道生活の魅力が非常に広まった要因であったようだ。

この禁欲主義は、中世中期の一般大衆の教会に対する認識において重要な要素であった。

11世紀から12世紀にかけて数千の修道院が建てられた。独身の禁欲的な男性で構成され、主に裕福な層から採用された修道院は、「教会全体の精神性、教育、芸術、そして文化の伝達の雰囲気の担い手だった…」。

修道士の祈りが全てのクリスチャンの助けになるという思想が、修道士の利他主義のイメージを育んだ。

これらの修道会は、非常に人気の大衆イメージを教会にもたらした。

13世紀の間、托鉢修道士達(ドミニコ会、フランシスコ会)は教会に対する教皇の権力を増大させ、聖職者の独身主義の規則を施行し、縁故主義や聖職売買を防止し、世俗権力に対抗する力を教会に与える教会改革に貢献した。それには信徒の性的関係を規制する権力の獲得等が含まれた。

「初期の托鉢僧は、最貧困層の最も搾取される人々に寄り添うように自発的に窮乏し自らに極貧を課していた。それらは世俗の聖職者の出世主義と虚飾、修道院の富と排他性とは全く異なっていた。それらは良心を突き動かし、商業コミュニティの気前の良さを刺激した。」

中世中期に…社会の最も有力で最も富裕、あるいは少なくとも豊かな層の多数のメンバーが、地上の快楽を最大限満喫する最良のチャンスを自ら断念したことは、歴史上最も驚くべき現象の一つである。…

新しい志願者の流れは、禁欲生活(修道生活)の規則が古代の厳格さに戻った地域、それどころか古代以上に厳しくなった地域で特に印象的であった。…

禁欲生活(修道生活)を選ぶ主な動機は、仮に長い人生の中でその原動力の一部を喪失したり、最初から他の動機が混ざっていたとしても、常に禁欲主義の世界終末論的理念があったと考えるべきであろう。

13世紀の間、托鉢修道士は基本的に貴族や地主などの裕福な家族から採用された。彼らの両親は普通の親がそうであるのと同じく孫を待ち望んだため、大抵それに反対した。

「裕福な家族にとって、子どもが修道士になることは悪夢だった」。これらの家族は、子どもが修道生活に勧誘されるのを避けるために子どもを大学に送るのをやめ始めた。

社会の中心にあったのは、人々は利他的であるべきであり、裕福に生まれても禁欲主義に生きるべきだというイデオロギーを持つ機関であった。

これが結婚とセックスに関して教会の権威が認められた理由であるが、そもそも、なぜ裕福な人々が修道院に入って禁欲(独身)を貫くことになるのか不思議である。

好き嫌いは抜きにして、この時期の西ヨーロッパは優生学と無縁であった。

中世の教会は西洋文化のユニークな特徴であったが、この論文のテーマは、批判的な意味で、それが最も非西洋的であったということにある。

なぜなら、中世ヨーロッパはグループアイデンティティとそれへの献身意識が強い集団主義の社会であったからだ。

私は、西洋社会は個人主義への献身においてもユニークであり、実際に個人主義が西洋文明を定義づけると以下で論ずる。

中世後期の西欧社会の集団主義はしっかりしたものだった。

例えば聖地をイスラム教徒の支配から解放しようとする十字軍遠征に伴う多数の巡礼者と宗教的熱狂、イングループ的な熱狂が示すように、社会のあらゆる階層でキリスト教への激しいグループアイデンティティと献身が存在していた。

中世の教会は、ユダヤ人に対するクリスチャングループの経済的利害の鋭い意識を持っていた。大抵の場合でユダヤ人の経済的・政治的影響力を阻止し、クリスチャンとユダヤ人の社会的交流を防ぐべく努力した。

以上のように、特に托鉢修道士、その他多数の宗教者、世俗エリートに至るまで、高レベルの生殖利他主義が存在した。

世俗エリートの生殖利他主義は主に強制の結果であったが、フランスのルイ9世のように自発的な抑制の場合もある。

ルイはクリスチャンの性道徳の模範であっただけではない。

彼はユダヤ人に対するクリスチャングループの経済的利害の鋭い意識も持ち、聖地をクリスチャンの手に取り戻すべく十字軍にも深く関与した。

ヨーロッパ人は、強力かつ脅威であった非クリスチャンのアウトグループ(特にムスリムとユダヤ人)に対し、自分達をクリスチャンのイングループの隊列の一員と見なした。

教会の力に基づく統一されたクリスチャン社会の理想と、エリートの間での性的抑制との間には、確かにギャップがあった。

しかしこれらのギャップに関しては、多くの中世クリスチャン、特に中世社会の主人公である以下の人々の認識を考慮するべきである。

修道院運動、托鉢修道士、改革派教皇、熱狂した十字軍、敬虔な巡礼者、更には多くのエリート貴族でさえ、彼ら自身を高度に統一された超国家的な集団の一員と見なしていた。

この根本的な集団主義志向を理解すれば、心理学の観点から中世の集団への激しい献身と利他主義とが分かる。それは現代の西欧とはあまりにも異質である。

西欧の社会的に課せられた一夫一妻制を保つ社会コントロール&イデオロギー

西欧では、教会は貴族の生殖の利益と正反対の教会式結婚モデルを採用した。その結果、12世紀末には家族構成の変化と教会による一夫一妻制の強制が起きた。

一夫一妻制の強制と維持には以下の要因が最も重要であっただろう。

離婚の禁止。

裕福な男性は簡単に再婚できるので、簡単に離婚できる場合の最大の受益者である。

ユーラシアの他の社会では離婚は一般的で、キリスト教以前のヨーロッパ諸部族の間でも合法であった。しかし教会の見解では結婚は一夫一妻制かつ不可逆であった。

クリスチャンローマ皇帝の下で離婚はますます制限され、9世紀から12世紀にかけて教会は貴族の離婚事件を争点にして貴族との紛争に勝利した。

例えば12世紀後半、フランス王フィリップは妻を嫌いでかつ妻が不妊であったにもかかわらず離婚を阻まれた。王はパリの修道院で宗教者グループに対し謝罪させられた。

離婚が許される場合もあったが、それは最初の結婚で男児の跡継ぎを産めなかった場合に限られた。例えば中世フランスのルイ七世とEleanor of Aquitaineの場合が当てはまる。

(しかし教皇は、ヘンリー八世が跡継ぎを産めない妻と離婚することを許可しなかった)

1857年の改革まで、イギリスでは離婚は「一握りの大金持ち以外には不可能だった」。しかしそれ以後でも離婚率は低さを維持し続けた。

「16世紀に離婚を合法化したヨーロッパの地域では、離婚率がグラフの横軸と区別できるようになるまで300年以上かかった」

イギリスでの離婚率は1914年まで0.1/1000以下、1943年まで1/1000以下だった。(Stone 1990)1910年当時、離婚率が0.5/1000を超えるヨーロッパの国は無かった。

私の知る限りでは、離婚を非常に避けるこの傾向は西欧文明特有である。

非嫡出子に対するペナルティ。

進化論の観点から、生殖に関する社会コントロールの最も重要な面は、内縁関係・事実婚のコントロールである。

非嫡出子のコントロールは、内縁関係・事実婚を困難・不可能にし、非嫡出子の財産相続を妨げる等で非嫡出子の将来性を危うくさせることで、裕福な男性の生殖利益を抑制する。

教会は内縁関係、特に正妻を差し置いての内縁関係を熱心に抑え込んだ。

非嫡出子の相続に対する社会コントロールは大抵効果的だったようだ。教会は、合法的結婚が合法の子供を産み、それ以外は法的地位を持たないという姿勢だったが、特定の時代には私生児は他の子供より地位が高かった。(see below)

私生児の相続財産は教会や国が没収したため、私生児に財産を残そうと願っても当局に阻止される可能性があった。

ピューリタン時代のイングランドでは、遺言状に私生児は一切登場しなかった。

教会の直接の影響力以外にも、世俗権力や世論によって、非嫡出子の出生にはその他様々なペナルティが科せられた。

非嫡出子の父親と特に母親には追放や投獄が科せられ、母親はその地域を去ることを含めて妊娠を隠すあらゆる努力をするのが普通だった。

これらの社会コントロールの影響は非嫡出子の死亡率にまで及んだ。近世の英仏では非嫡出子の方が乳児死亡率が高かった。

女性は非嫡出子を大抵捨てた。非嫡出子は大抵死産として報告され、嬰児殺しを暗示しており、女性は時として堕胎によって非嫡出子の出産から逃れようとした。

エリートに対する内縁関係の統制。

中世にはエリート男性に対する内縁関係の統制はますます効果的になった。よって12世紀は極めて重要であろう。

この時代の例には、一夫一妻制を支持する社会・イデオロギー的コントロールをうまく回避したエリート男性たちの話もあり、エリート男性でありながら完全な一夫一妻制を守った話もある。

一般のパターンは、英国王の非嫡出子の数から読み取れる。1066年から1485年までの18人の英国王の内で10人が愛人を持ち、恐らく計41人の非嫡出子を持った。

1100年から1135年のヘンリー一世は、この内20人を持ち、さらに5人の非嫡出子を持つ可能性もある。中世では他に三人以上の非嫡出子を持った王はおらず、八人の王は非嫡出子を持った記録が無い。

ヘンリー一世は領土的野心のために大量の子孫を欲したユニークな王である。それでもヘンリーは非嫡出子を嫡出子より遥かに酷く扱った。嫡出子は甘やかされ、宮廷で手ほどきを受け、大貴族の生活が約束されていた。

一方で私生児は王位継承から除外され、大抵は結婚のチャンスすら無かった。

12世紀に起きた結婚に関する考え方と慣習の大きな変化を反映して、その後数世紀で非嫡出子の数と重要性は低下した。

中世以降の性行動の取り締まり。

中世の教会の主な目標の一つは、一夫一妻制の結婚外での性行為を取り締まることであった。性的違反の取り締まりは中世から少なくとも17世紀末まで教会裁判所の重要な仕事であった。

これらの裁判所は17世紀のイギリスで非常に活発で、淫行・姦通・近親相姦・違法同居などを訴追した。

これらの教会の処罰の有効性は地域と時代により異なるが、「犠牲者は仲間に追い回され、村八分にされて生計を奪われ、追放者として扱われた」という悲惨な結果の例もある。

17世紀の高等宗務官裁判所には、他の司法手続きから免除されそうな富裕層に対し、姦通に対する制裁を含めた制裁を課す権限が認められていた。

「法の下の平等のこのような強制執行により、裁判所は17世紀のイングランドの重要人物たちに嫌われた」。

治安判事などの世俗当局も、それらの犯罪を訴追する用意があった。例えばエリザベス朝の法令に基づき16世紀と17世紀の治安判事たちは、男女の性犯罪者に対し、さらし台に拘束し、腰まで服を脱がせて(女性は「背中が血まみれになるまで」)公開鞭打ち刑に処すと宣告するのが普通だった。

一夫一妻制を促進するイデオロギー。

最終的には社会コントロールに依存していたものの、中世の教会は一夫一妻制と性的抑制を促進するべく巧みなイデオロギーを発展させた。

一般にこれらの著作は、独身主義の道徳的優位性とあらゆる種類の婚外性行為の罪深さを強調した。一夫一妻制の結婚以外での全ての性関係は、近世から現代にいたるまで宗教権威によって例外なく非難された。夫婦のセックスは嘆かわしく罪深いがやむを得ないものとされ、妻に対する過度の情熱は姦淫と見なされた。

18世紀には比較的緩和されたが、19世紀には激しい反快楽主義の宗教的性イデオロギーが台頭した。

結論。

中世以来、社会コントロールとイデオロギーの巧みなシステムが、西欧の広い地域で程度の差はあれ一夫一妻制の完全な押し付けに成功した。

「中世初期の大きな社会成果は、富裕層と貧困層の双方に同じ性行動・家庭行動のルールを課したことにある。王は宮殿にいて、農民は小屋にいたが、例外は無かった。」

とはいえこのシステムは決して完全な平等主義では無かった。工業化以前のヨーロッパでは富と生殖の成功の間の正の相関があった。

西欧では一夫多妻制にペナルティを課して非一夫一妻制を生殖と関わらないものに変えたり、完全に抑圧する等の、驚異的な継続性を持つ様々な慣例があった。

これらの慣例の変化や政治・経済構造の大変化にも関わらず、ローマ文明から始まる西洋の家族制度は明らかに一夫一妻制の社会的押し付けを目指してきた。この努力は大部分成功した。

一夫一妻制の効果

一夫一妻制は西洋のユニークさの中心的面であり、複数の重要な効果を持つ。

一夫一妻制はヨーロッパ特有の「低圧」人口動態の必要条件である可能性が高い。この人口動態は、経済的欠乏期に高い割合の女性が晩婚になったり独身になった結果である。

一夫一妻制との関連で言えば、一夫一妻制の結婚では男女ともに貧しい者は結婚すらできない状態になる。しかし一夫多妻制では、貧しい女性が過剰にいても、裕福な男性にとって側室の価格が安くなるだけである。

例えば、17世紀末には40~44歳の未婚率は男女共に約23%であった。しかし経済的チャンスの変化に伴って18世紀初頭にはこの割合が9%まで低下し、それに伴い結婚年齢も下がった。

このパターンは一夫一妻制と同様、ユーラシアの階層社会の中ではユニークであった。

同様に、低圧の人口動態は経済状態にも影響したようだ。

結婚率は、人口増加の主な抑制要因であっただけではない。特にイギリスでは好景気に対応する結婚率の上昇が大きく遅れる傾向があったため、人口増加が食料供給にかける圧力より好景気時の資本蓄積の傾向が強かった。

経済の変動と人口動態の変動の間のローリング調整はこのように緩慢に発生した。実質賃金は緩やかに大きく上昇する傾向にあったので、産業革命以前の全ての国の飛躍を妨げてきた低所得の罠から抜け出すチャンスを得た。

実質賃金の長期的な上昇は需要の構造を変化させ、生活必需品以外の商品の需要を不釣り合いに強く押し上げる傾向がある。産業革命が起きた場合は生活必需品以外の部門の成長こそが特に重要になる。

よって一夫一妻制は、工業化の必要条件である低圧の人口動態をもたらしたと考えることもできる。

全体を見れば、女性の晩婚化・独身化がワンパターンで進んでいるわけでは無い。それより、結婚は経済的制約に左右される。

豊かな時代には男女共に結婚年齢が低下し、子供を残さない女性は減った。その結果、リソースの利用能力に非常に左右される結婚制度になった。

「ヨーロッパの重要かつ飛び抜けた特徴は、システム転換の軸となった、人口を経済に適応させる柔軟な結婚制度であった」

これは、一夫一妻制が西洋近代化に不可欠な基本概念の中心面であった可能性を示唆する。

一夫一妻制と子どもへの投資

一夫多妻では、リソースが生殖に割かれて子供への投資が比較的少なくなる傾向がある。一夫多妻の男性にとっては、追加の妻や側室、投資額が少なく済む彼らの子供に向けて追加投資するのが魅力的である。

一夫多妻社会では、追加の側室に投資すれば報酬が大きい傾向があり、その子供への投資も安く済む。

側室の子供には比較的小さな遺産が与えられ、社会的地位は下がるのが一般的であった。

ハーレム女性の子孫の性比は低く、圧倒的に娘が多い。理論的には、一般的に女性の方が交尾しやすいため、低投資で済む子孫に偏ることを示す。

これら側室の娘は父親に比べて社会的地位は低いものの、交尾はしやすい傾向にある。一方で上流階級の息子は身分の低い一族からの持参金競争の対象となった。

いずれにせよ、父親が側室の子供に時間・労力・金銭を投資する必要は殆ど無い。

しかし一夫一妻では、個々の男性が投資できるのは一人の女性の子供に限られる。

拡大された親族関係が衰退し(see below)、全ての社会階層で一夫一妻が制度化されると、 子どもたちへの支援は独立した核家族次第になった。

後述のように、この「シンプルな」家族こそが西洋近代化の決定的手段であった。

拡大血縁(extended kinship relations)の衰退と単純世帯の台頭

一夫一妻制の場合と同じく、拡大血縁の衰退にも教会が関与した。

しかしこの場合の教会の政策は、強力な中央政府の台頭に助けられた。中央政府は拡大された家族関係を抑制し、個人の利害を保証することで拡大家族の役割を継承した。

進化論の観点からは、親族関係の潜在的な重要性を過大評価するのは難しい。

生物学的血縁関係のために親族は共通の利害を持ち、協力や自己犠牲行動への閾値も低いであろう。

ローマ帝国末期に西欧の大部分に定住したゲルマン諸部族は、男性間の生物学的血縁関係に基づく血縁グループとして組織化されていた。彼らは血縁の絆に基づく強いグループ連帯感を持っていた。

「初期のゲルマン人は攻撃や飢饉の脅威に直面しても、官僚的帝国の保護と支援に頼ることができなかったため、共同体の各男女は家族や共同体の連帯の絆が体現するグループ・サバイバルという社会生物学の基本原則に固執する義務があった」。

この部族に基づく血縁集団の世界こそが、王や教会が根絶したいものだった。

拡大血縁に対する反対勢力

大規模かつ強力な血縁グループを根絶することは教会と貴族の双方にとって利益があった。

高度に中央集権化された国家権力は、それ自体で拡大血縁の重要性を下げる傾向があり、その権力が個人の利益を保護する場合には特にそうなる。

進化論の観点から見れば、拡大血縁グループはコストと利益がある。

利点はより広い親族から提供される保護と支援であるが、この利点にはコストも伴う。

1)親族からの互恵的なサービスの要求が高まる

2)親族は、ある個人が親族集団の中で他の人より過度に出世するのを妨害する傾向がある事実

3)平等主義と程遠い親族構造の中で自己を確立する困難さ

結果として、自分の利益が他の制度によって保護されている場合、例えば拡大血縁の利益は無くコストだけがある場合には、個人は拡大血縁グループに絡まるのを避けるであろう。

一般に、中央集権が弱体化すると、個人は拡大血縁グループの保護を求める傾向があり、国家権力が自分達の利益を充分守れる力を持つ場合には、それに伴って拡大血縁グループから逃げ出す。

単純な家族に基づき近親者への義務から解放された貴族が、単純な家族構造の農民を支配し、拡大血縁とは違う隣人や友人から成る社会に組み込まれた。それが、徐々に発展した西洋の図式である。

この社会構造は中世後期の成果である。中世後期には、英仏の農民にとって拡大血縁は重要ではなくなっていた。

教会の政策。

教会の政策の一つとして、教会は近親婚(近い血縁の結婚)に反対し、双方の同意のみに基づく結婚を支持して、西欧での拡大血縁の絆の根絶に貢献した。

近親婚については、教会は拡大し続ける個人の集団の間での結婚を禁じた。六世紀にはまたいとこまで、11世紀までには6th cousins、つまりgreat-great-great-great-great grandfatherが共通になる個人にまで禁止が拡大された。

明らかに、これらの近親婚の禁止の範囲は進化論で予測できる範囲より遥かに広い。

加えて、同様に遠い、婚姻で生じた親族(結婚で親族になった場合)や精神的親族の個人間(代父母としての親族)でも結婚は禁じられており、生物学的血縁は重要とされなかった。

この政策の効果は、拡大血縁のネットワークを弱体化させ、より広い親族グループへの義務から解放された貴族を生み出した。

教会のこれらの禁止命令がどのように正当化されたにせよ、貴族が教会の規則に従った証拠がある。

十世紀から十一世紀のフランス貴族の間で、4th or 5th cousinsより近い親族間の結婚はほとんど起きなかった。

これらの慣習は、近親婚の範囲の拡大が「結婚による血縁の強化」を排除して拡大血縁グループの連帯を妨げたので、拡大血縁グループを弱体化させた。

その結果、生物学的血縁が社会の頂点に集中することなく、貴族全体に分散して広がった。

より広い親族グループだけでなく家族の直系の子孫も恩恵を受けた。「世俗の高い地位の男性は、…自分の直系の子孫のためにできるだけ自分の財産と家族を一元管理しようとし、より広い親族は二の次だった」。

近親婚に対する政策に加えて、結婚における同意という教会の教義が、拡大血縁に対抗する力として働いた。

「家族・部族・氏族は個人に従属していた。もし結婚したいなら、自分で相手を選ぶことができ、教会はその選択を弁護する」。結婚は同意の結果として起こり、性交によって批准された。

結婚の基礎を、家族や世俗支配者の支配から当事者自身に譲渡させることで、教会は伝統的親族・家族の絆に対抗する権威を確立した。

結婚相手の選択の自由は近代を通してイングランドの原則であり、親のコントロールは人口の上位1%でのみ起こった。

西洋個人主義の民族的基盤

Magian(東方人)の人間は、上から下に降順で整列しており、「我々」なるものの空っぽな一部分にすぎず、全てのメンバーが代わり映えが無い。

肉体と魂としては彼は自立しているが、異質で高次な別のものも彼の中に宿っている。それは彼の全ての気配と信念とを単なるコンセンサスの一員にする。それは神の放出物として、自我の自己主張の可能性を排除する。

彼にとっての真理は、我々、特にヨーロッパ精神を持つ我々にとっての真理と全く異質である。

個人の判断に基づく我々の認識論的方法は全て、彼にとっては狂気とのぼせ上がりである。その科学的結果は、その真の性質と目的において精神を混乱させ欺く邪悪な所業である。

この洞窟の世界の中にはMagianの究極かつ近寄りがたい秘密がある。自我が考え・信じ・知ることの不可能性こそが、これらの宗教の基礎の前提にある。

ファウストの世界観

「Wolfran von Eschenback、セルバンテス、シェイクスピア、ゲーテにとって、個人の人生の悲劇の線は、内側から外側へ、ダイナミックに、機能的に発展する」。

「…神が見せる、または見せたと言われる仮面の言葉が、殴っても空々しく聞こえるならば、神を疑うことさえする」オズワルド・シュペングラー

これまでのところでは、同意と愛、一夫一妻制、拡大血縁の重要性の低下に基づく個人主義的な核家族の出現は、単に私が述べた社会プロセスの結果に過ぎないと思う人もいるだろう。

しかし実際には、これらの変化が世界の他の地域より遥かに素早くかつ徹底的に発生したのである。

西洋世界は、個人主義の全てのマーカーが基本的な特徴である唯一の文化圏であり続けている。一夫一妻制、夫婦の核家族、国家に対抗する個人の権利としての代議制政府、道徳普遍主義、科学。

更に言えばこの文化は、これら特徴を幾つか備えたローマ文明の強固な基盤の上に築かれた。

よって私は、これらの傾向は西欧文化圏のユニークなものであり、民族的基盤が支えていると提唱する。

西欧人がユニークな生物学的適応を果たしているとまでは思わないが、全人類は適応の特徴の程度にそれぞれ違いがあり、ユニークな文化の進化を可能にするには十分な量の違いがあっただけである。

同様に、全ての人間は象徴表現や言語のような特徴的な精神的能力を備えているが、文化に大きな影響を与えるには十分な量の人種間のIQの違いが存在する。恐らく、少なくとも質的な違いをもたらすには十分な量の違いがある。

私は、最近の進化の過程で、ヨーロッパ人はユダヤ民族やその他の中東の人種集団と比べてグループ間自然選択を受けにくかったと提唱する。

これは元々Fritz Lenzが提唱したもので、氷河期の厳しい環境のために北欧人は少人数グループで進化し、社会的孤立の傾向があるというものだ。

この観点は、北欧人がグループ間競争に必要な集産主義メカニズムを持っていないことを示唆するものでは無い。集産主義メカニズムが比較的巧みではない、そして/またはメカニズム発現に、より激しいグループ間紛争が必要だと示唆している。

この観点は生態学の理論と一致する。生態学的に不利な環境下で、適応は他のグループとの競争よりも不利な物理環境に対処することに向けられる。そのような環境下では、拡大血縁ネットワークや高度集産主義グループに対する選択圧力は弱いであろう。

進化論的なエスノセントリズムの概念化は、イングループ競争でのエスノセントリズムの有用さを強調する。したがってエスノセントリズムは物理環境との格闘では全く重要でない。また、そのような環境は巨大なグループを支えられないであろう。

ヨーロッパ人グループは北ユーラシア・北極周辺の文化圏の一部である。この文化圏は、寒冷で生態学的に不利な気候に適応した狩猟採集民に由来する。

このような気候では男性が家族を養う圧力と一夫一妻制に向かう傾向がある。生態が、進化的に重要になる期間に一夫多妻制と大グループを支えなかったからである。

これらの文化では、男性と女性の両系統が双務的に重要になる親族関係が特徴であり、一夫一妻制の条件下で期待される以上に両親の貢献度が対等になると示唆される。

また、拡大血縁は重視されず、結婚は族外婚、つまり親族グループの外に向かって起こる傾向がある。

これらの特徴は全て、ユーラシア南部の旧世界中央部の文化圏の特徴とは反対である。この文化グループにはユダヤ人やその近縁の近東グループがある。

このシナリオは、北欧人が個人主義に向かいやすいことを示唆する。なぜなら彼らは拡大血縁に基づく巨大な部族グループを支えられない生態的環境に長期間住んでいた。

ミトコンドリアDNAによると、ヨーロッパ人の遺伝子の約80%は三~四万年前に中東からヨーロッパに到着した人々に由来する。

これらの集団は氷河期を生き延びた。四万年間北部の寒い曇りの環境で進化したヨーロッパ人は、金髪と青い目だけでなく環境に適応した気質と生活様式の嗜好を発達させたであろう。

これらの人々は農耕種族ではなく、狩猟採集民であった。経済生産のレベルは比較的低いため、狩猟生活では男性は女性を得やすい。

なぜなら、人間の脳に必要なエネルギー量は質の高い食事でのみ満たされるからである。

人間の脳は体重の2%しかないが、全エネルギーの20%を消費し、胎児期には70%を消費する。

これが、一夫一妻の心理的基盤であるつがいの絆(女性が育成し男性が養育する協力体制)を五十万年前から始めさせた。

狩猟には「相当な経験、質の高い教育、長年の集中的な実践」も必要だった。言い換えればこれは高投資の子育てである。

また人間の狩猟は、走力や体力よりも認知能力に左右されるため、知能も必要である。

狩猟のシナリオは複雑かつ常に変化する。どの動物種、個体も、性別・年齢・気候・地形などの内的条件に応じて固有の行動特性を示す。

これらの傾向は全て、単位面積当たりのエネルギーが少ない北方で強い。

歴史的証拠が示すところでは、ヨーロッパ人、特に北西ヨーロッパ人は、強力な中央政府が台頭して自分達の利害が保護された時、比較的早く拡大血縁ネットワークと集産主義の社会構造を捨てた。

中央の権威が台頭すると、世界の普遍的傾向として拡大血縁のネットワークが衰退する。

しかし北西ヨーロッパの場合では、この傾向は遅くとも中世後期までには早くも台頭し、それ以前に既に西欧特有の「単純世帯」は生まれつつあった。

単純世帯は、一夫一妻とその子供たちが基本である。

この世帯のタイプは、フィンランドを除くスカンジナビア・イギリス諸島・ネーデルラント・ドイツ語圏・北フランスで典型的である。

これはユーラシア他地域で典型的な、兄弟とその妻の二組以上の親族カップルから成る共同世帯構造とは対照的である。

産業革命以前の単純世帯は、結婚年齢は遅く、未婚の若者を使用人として働かせて富裕層の家庭の間をぐるぐる回らせることが特徴であった。

共同世帯は、男女とも結婚年齢は早く、出生率は高く、必要に応じて二つ以上の世帯に分離できることが特徴であった。

この単純世帯システムは、個人主義文化の基礎の特徴である。

個人主義の家族は拡大血縁の義務と制約から解放され、世界の他地域で典型的な息苦しい集産主義の社会構造からも解放され、家族自身の利害を追求できるようになった。

個人の同意と夫婦の愛に基づく結婚が早い時期に、親族関係と懸念事項に基づく結婚に取って代わった。

単純世帯の形成に向かうこの比較的強い傾向は、民族性に基づくであろう。

過酷な気候に適応した人々にとって、単純世帯は生態学的に合理的であるだけではない。以前に指摘したように、この傾向はゲルマン民族の間でより強い。

英仏海峡のサンマロとフランス語圏であるスイスのジュネーブを結ぶ「永遠の線」から北東に住むゲルマン民族の区分に対応して、フランス国内に大きな違いが存在することは興味深い発見である。

この地域は18世紀の農業革命以前から、成長する町や都市を養える大規模農業を発展させていた。

それを支えたのは町の熟練職人たちであり、中規模農家たちが形成する大きな階層であった。

彼らは「馬、銅のボウル、ガラスの杯、大抵は靴も持っていた。彼らの子供達は頬がふっくらしており、肩幅は広く、赤ちゃんまで小さな靴を履いていた。これら子供たちは誰も第三世界のくる病の膨れた腹をしていなかった。」

北東部はフランスの工業化と世界貿易の中心になった。

北東部は識字率でも南西部と差があった。19世紀初頭、フランス全体の識字率は約50%に対し、北東部は100%近く、少なくとも17世紀から差が生じていた。

更に身長でも顕著な差があり、18世紀の新兵のサンプルでは北東部の人々の方が2センチ近くも背が高かった。

Ladurieは以下のように指摘した。軍は南西部の背の低い人々をあまり受け入れないため、人口全体で見ればその差はもっと大きいであろう。

家族史家は以下のように指摘した。経済的に独立した核家族への傾向は北部で顕著であり、南東部に移るにつれて共同世帯への傾向が見られる。

これら調査結果は、民族の違いがヨーロッパでの家族形態の地理的違いに寄与していることを強く示唆する。

ゲルマン民族は進化の過程で資源が乏しい北欧で自然選択されたため、個人主義に向かう生物学的傾向が強く、核家族の社会構造へ向かう傾向も強いことが示唆された。

これらグループは拡大血縁グループにあまり魅了されず、拡大血縁ネットワークの衰退に伴って状況が変化すると、単純世帯の構造が素早く出現した。

この単純世帯の構造が比較的容易に採用されたのは、このグループがすでにそのユニークな進化の歴史によって、単純世帯システムに向かう比較的強い心理的素因を持っていたからである。

ゲルマン民族とヨーロッパ他地域の間のシステムの違いは重要ではあるものの、西欧とユーラシア他地域との間の全般的違いほど大きくはない。

単純世帯に向かう傾向と人口動態の変動は北西ヨーロッパで最初に生じたが、比較的早期に全ての西洋諸国に広がった。

西洋のユニークさのもう一つの要素として、単純世帯を特徴とする北西ヨーロッパの農民家庭では、若者を他の家庭の使用人に送り出す慣習があった。

工業化以前のイギリスでは30~40%の若者は他人の家庭に使用人として出向いており、使用人は20世紀まで最大の職業グループであった。

使用人を雇う慣習は、単に外部の人間を導入して誰かのニーズを満たすだけにとどまらない。

人々は時には自分の子供達を使用人に送り出すと共に、同時に縁のない使用人を受け入れた。

使用人になったのは貧しい土地を持たない人々の子供達だけではない。裕福な大農家でさえ子供たちを使用人としてよそに送り出した。

17、18世紀には、人々は結婚後早い段階で、自分の子供達が仕事を手伝えるようになる前に使用人を受け入れ、子供が十分成長して人手が余ったら子供をよその家庭に使用人として送り出した。

これは、深く根付いた文化的慣習が、結果として親族関係に基づかない高水準の互恵関係に結びついたことを示唆する。

この慣習はまた、非親族を世帯の一員に迎え入れるという、相対的なエスノセントリズムの欠如も物語っている。

これらの工業化以前の社会は、拡大血縁を中心に組織されたものでは無く、産業革命と近代世界にあらかじめ適応していたことが容易に理解できる。

ユーラシア他地域では、世帯は親族だけで構成される傾向が強かった。

興味深いことに、古典的中国のような性競争社会では、女性使用人は家長の側室になりやすく、世帯のリソースを直接生殖に回すことができた。

よって西欧モデルでは、裕福な男性はユーラシアの性競争社会よりもはるかに多くの非親族を養っていた。

過酷な気候で生きる狩猟採集社会が大抵、肉などのリソースの共有を目指す非常に巧みな相互扶助のシステムを持つことは興味深い。

工業化以前の西欧に非常に典型的な、非親族同士の相互扶助のシステムも、過酷な北方の気候で長期間進化してきた遺品の一つではないだろうか。

親族社会のしがらみから解放された単純世帯の確立の後には、西洋近代化の他の全てのマーカーが続いた。

個人が国家に対して権利を有する制限された政府、個人の経済的権利に基づく資本主義経済企業、個人主義的な真理の探究としての科学。

個人主義社会は共和制の政治制度と科学的探究の制度を発達させ、グループは最大限の透過性を持ち、個々のニーズを満たせない場合には離反される可能性が高いであろう。

個人主義の結婚。結婚の基礎である同意・愛・伴侶関係。

夫婦の同意に基づく単純世帯の台頭は、家族が拡大血縁のしがらみの中にある状況と比較して、結婚相手の個人的な資質がより重要になったことを意味した。

拡大家族が支配する状況では、結婚は一般的に血族婚になり、家族の戦略に左右される。

単純世帯システムでは、結婚相手の個人的特性がより重視される。知能、性格、心理的相性、社会経済的地位などである。

集産主義社会が結婚の際に家系や遺伝的血縁の程度を重視するのに対して、個人主義社会は個人的魅力、例えば恋愛や共通の利害を重視する傾向がある。

ジョン・マネーは、北欧人のグループが結婚の基礎として恋愛を重視する傾向が比較的強いことを指摘した。

Frank Salterは以下のように提唱した。北欧人グループは性行動に関して多くの個人主義的適応を持つ。それには寝取られを防ぐための社会コントロール機構よりむしろ、恋愛や遺伝特性へのより強い傾向がある。

心理的なレベルでは、個人主義の進化論的基盤には、集産主義文化のように家族の戦略や強制によって課されるのではなく、適応的行動が本質的にやりがいがある、恋愛のようなメカニズムが含まれる。

これは、自由に同意できる多かれ少なかれ平等なパートナー間の個人的な求愛と、女性の見合い結婚が成立するまで男性親族に隔離・管理される近東のpurdahの制度の違いである。

中世からパートナー間の愛情と同意に基づく伴侶結婚に向かう傾向が始まり、最終的には高位の貴族の結婚の決定まで左右するようになった。

「大半の社会とは違い、西洋の工業社会では男性と妻の感情の関係が第一優先される」

実際、これは東洋と西洋の階層社会の間で普遍的に異なる点である。

一夫一妻の結婚の基礎としての恋愛の理想化は、古代末期のストア派や19世紀のロマン主義などの西洋の世俗知的運動をも周期的に特徴づけてきた。

他の社会で配偶者間の愛情が存在しないという訳ではない。西洋社会ではそれがより重要であるというだけだ。

中世以来の西洋の結婚の特徴としての、結婚への個人の同意は、結婚相手の個人的な特徴をより重視する個人を生み出すであろう。

その効果の一つは、結婚相手の年齢の平準化である。結婚年齢が比較的平準であることと晩婚化は、西欧結婚システムの特徴である。

女性の結婚年齢は、西欧ではユーラシアやアフリカの他地域よりも高く、これは共同家族が特徴の西欧農民社会を含めても同じ傾向だった。

実際、1550-1775年のイギリスの大規模なサンプルでは、女性の平均結婚年齢は1675年まで26歳前後で変動していたが、1800年には24歳過ぎにまで低下し始めた。

単純世帯がもたらしたもう一つの結果は、愛情とつがいの絆が結婚の基礎になったことである。

結婚は、親族グループ間や親族グループ内での政治同盟、純粋な経済関係、単なる性的競争の側面としては重要性を失い、愛情を含む対人魅力に基づくようになった。

結婚生活での愛情は、単純世帯の台頭と共に文化的な規範となった。

西洋の求愛現象(ユーラシア・アフリカ文化の中でユニークな)は、将来の結婚相手が個人の相性を評価できる期間を提供した。

マルサスの言葉を借りれば、両性に「同類の気質を見出し、結婚生活が幸福より不幸を多く生むことにならないよう、強く持続的な愛着を形成する」機会を与えた。

ヨーロッパ人の個人主義と民族意識の低下

ここまでで私が描いたシナリオの要約は以下である。西ヨーロッパ人が比較的エスノセントリックでないのは、拡大血縁が比較的機能しない悪環境の下で長期間自然選択されてきた結果である。

西欧人は拡大血縁の束縛から解放され、原点回帰し、近代化の原動力となった単純世帯を容易に採用した。伴侶結婚、国家に対抗する個人の権利、代議制政府、道徳普遍主義、科学。

その結果、創造性、征服、富の創造などの、現代まで続く並外れた時代が到来した。

しかし、ユダヤ教に関する私の著作のテーマの一つは以下である。個人主義は、凝集的グループ戦略に対して貧弱で無力な戦略である。

西洋では、近代化に必要な前段階として拡大血縁グループが排除されたが、グループ間競争が全面的に排除されたわけでは無い。

19世紀以降、集産主義者で民族意識が強いユダヤ人たちと、西洋個人主義エリートたちとの間で競争が起きた。

人類学的には、ユダヤ人は旧世界中部の文化圏に由来する。

この文化圏は、西洋社会組織の特徴とは正反対である。Table 1に示すように、ユダヤ教は集産主義であり、エスノセントリズム・xenophobia(外国人憎悪)・moral particularism(道徳非普遍主義)に陥りやすい。

Table 1 省略

ユダヤ教に関する私の著作では、個人主義社会は、歴史的にはユダヤ教が代表する凝集的グループの侵略に対して特に脆弱であるというテーマが随所に登場する。

進化経済学者の最近の研究は、個人主義文化と集産主義文化の違いについて、興味深い洞察を提供する。

この研究の重要な面は、個人主義グループ間の協力の進化をモデル化する点にある。

人々は「ワンショットゲーム」で離反者を利他的に罰する。このゲームでは参加者同士は一度しか交流せず、交流相手の評判はゲームを左右できない。

この状況は、参加者は親戚関係のない他人であるため、個人主義文化をモデル化している。

驚くべき発見として、公共財の寄付を高水準で行った被験者は、寄付しない参加者を、罰するコストをわざわざ費やしてまで罰する傾向があった。

そして、罰せられた人は、以降のラウンドの参加者が前のと違うのを知っていたにもかかわらず、戦略変更してより多くの寄付をするようになった。

研究者たちは以下のことを提唱した。個人主義文化圏の人々は、free ridingに対するネガティヴな感情反応を進化させ、自分がコストを払ってでもフリーライダーを罰するようになった。これは”altruistic punishment”(利他的罰)と呼ばれる。

この研究は本質的に、個人主義の人々の間の協力の進化モデルを提供する。

彼らの結果は個人主義グループに最も当てはまる。なぜなら、そのようなグループは拡大血縁グループに基づいていないため、離反がより起きやすい。

高レベルの利他的罰は一般的に、拡大家族を基盤とする親族ベースの社会より、個人主義の狩猟採集社会で多く見られる。

彼らの結果は、ユダヤ人グループや他の高度集産主義グループのような、伝統社会では拡大血縁・既知の親族関係・メンバー間の繰り返しの相互関係に基づくグループには、ほとんど当てはまらない。

そのような状況では主体者は拡大血縁ネットワークに巻き込まれており、もしくはユダヤ人のように民族グループで固まっているため、協力者を知っており、将来の協力への期待も込みである。

よって、ヨーロッパ人は正にこの研究がモデル化した類のグループである。

彼らは拡大家族のメンバーとよりも見知らぬ人との協調性が高いグループであり、マーケットでの関係や個人主義に傾倒しやすい。

これは以下のような魅力的な可能性を示唆する。ヨーロッパ人同士を互いに離反させようとするグループにとっての鍵は、ヨーロッパ人自身が道徳的非難に値することを彼らに納得させることで、ヨーロッパ人同士の間で利他的罰を引き起こさせる点にある。

ヨーロッパ人は根っからの個人主義者であり、他のヨーロッパ人がフリーライダーであり道徳的非難に値すると見なすと、道徳的怒りでそのヨーロッパ人に対して容易に決起する。これは、狩猟採集民として進化した過去に由来する、利他的罰への強い傾向の発現である。

利他的罰の判断を下すのに、相対的な遺伝距離は無関係である。フリーライダーはマーケットにおいて見知らぬ人であり、つまり彼らは利他的罰を行う側とは家族・部族のつながりは無い。

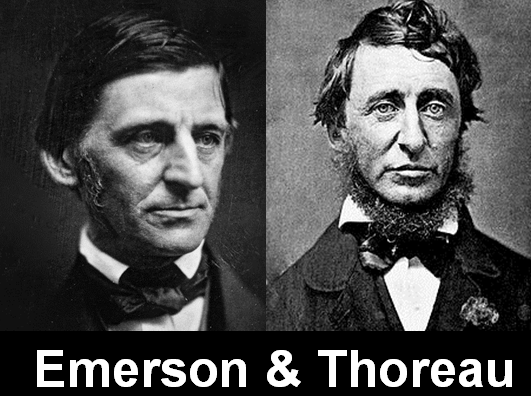

ピューリタンは、利他的罰を求めるこの傾向の典型例として、非常に興味深く影響力のあるヨーロッパ人グループである。

ピューリタンの決定的特徴は、道徳問題としてユートピアの大義を追求する傾向である。彼らは’よりハイレベルの法’に対するユートピア的訴えや、政府の主要目標は道徳にあるという信念に左右されやすい。

ニューイングランドは「人間の信念を完成させ」、「沢山の’isms(主義)’の生みの親」になるのに最も適した肥沃な土地であった。

政治的代替案を、一方を悪魔の化身として、他方を道徳的に必要不可欠なものとして、極端に物事を対照的に考える傾向があった。

ピューリタンの道徳的熱情は、彼らの「深い個人的な敬虔さ」、つまり聖なる生活だけでなく厳格で勤勉な生活を送りたいという彼らの献身への熱意にも見て取れる。

ピューリタンは道徳的正しさを求めて、自分達の遺伝的いとこに対してさえ聖戦を繰り広げた。

これは、拡大血縁に基づくグループよりも、協力的な狩猟採集グループの間で多く見られる利他的罰の一形態であることが示唆される。

例えば、南北戦争につながった政治・経済の複雑さがどうであれ、ヤンキーの奴隷制に対する道徳的非難がレトリックを左右し、アフリカからの奴隷の代理人として英米人の近親者同士が行った大規模な殺戮はピューリタンの中で正当化された。

軍事的には南部連合との戦争は、アメリカ人の生命と財産にこれまでで最大の犠牲を強いた。

ピューリタンの道徳熱と、悪人への厳罰を正当化する傾向は、以下のコメントにも見て取れる。「ニューヨークのHenry Ward Beecher’s Old Plymouth Churchの会衆派牧師は’ドイツ人を絶滅させ…1000万人のドイツ兵の不妊手術と女性の隔離’を呼び掛けるほどだった」。

これらが現代西洋文明に特徴的な、現在見られるような利他的罰である。

一度ヨーロッパ人が自分達自身の民族が道徳的に破産したと確信したら、あらゆる罰の手段を自分達の民族自身に対して用いるであろう。

他のヨーロッパ人を包括的な民族・部族共同体の一部と見なすよりも、同じヨーロッパ人を道徳的非難に値する存在と見なし、利他的罰の標的と見なした。

西洋人にとっては道徳は個人主義的である。フリーライダーが共同体規範を侵害すると、利他的攻撃で罰せられる。

一方で、ユダヤ教のような集産主義文化に由来するグループ戦略は、親族関係やグループの絆が優先されるため、それら策略に対して免疫がある。

彼らの道徳は非普遍主義である。グループの利害のためならどのようなことも正当化する。

これらグループの進化の歴史は、見知らぬ人とではなく親族同士との協力が中心であったため、利他的罰の伝統を持たない。

よって、ヨーロッパ人を破滅させる最良の戦略は、ヨーロッパ人に自身の道徳的破産を確信させることである。

私の著作「The Culture of Critique(批判の文化): An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements」の主題は、これこそがユダヤ人知的運動がやってきたことだと証明する点にあった。

彼らは、ユダヤ教はヨーロッパ文明よりも道徳的に優れており、ヨーロッパ文明は道徳的に破綻しており、利他的罰の標的に相応しいと訴えてきたのだ。

その結果、ヨーロッパ人は自身の道徳的堕落を一たび確信すれば、利他的罰の発作で自分達自身を破滅させようとする。

道徳的な猛攻が利他的罰の発作を誘発した結果として、西洋の文化が全面的に解体され、最終的に民族の実体のようなものさえ死滅するようなことが起きる。

こうしてユダヤ人知識人たちの間では以下の激しい努力が見られる。ユダヤ教の道徳的優越性と歴史上の不当な被害者の役割のイデオロギーを維持する努力。同時に、西洋の道徳的正当性を猛攻撃する継続的努力。

つまり、個人主義社会は、ユダヤ教のような高度集産主義・グループ最優先の戦略を持つ人々にとって望ましい環境である。

非ヨーロッパ系移民の問題が、米国のみならず西洋世界全体で深刻かつ争点だらけの問題となり、他地域では全くそうなっていないことは重要である。

ヨーロッパ起源の民族だけが、世界の他の民族に門戸を開いて、数百年占有してきた自民族の領土の支配権を失う危険にさらされている。

そして彼らは大部分、移民活動家たちが自身の民族的目標を達成するべく巧みに利用した道徳的反省に、引っ張られ誘導されていた。

西洋社会には個人主義ヒューマニズムの伝統があり、それが移民制限を困難にしている。

例えば19世紀には最高裁は、中国人排斥法を、個人に対してではなくグループに対して立法しているという理由で二度却下している。

移民制限の知的根拠を構築する努力の道には紆余曲折があった。

1920年まで、移民制限論は北西ヨーロッパ人の民族的利害の正当性を根拠としており、人種主義の思想を帯びていた。

これらの発想はいずれも、Israel Zangwill等のユダヤ人移民推進活動家が強調したように、人種・民族グループへの帰属が公的な知的是非を問われない共和制・民主主義社会の政治・道徳・人道イデオロギーとの調和が困難なものであった。

1952年のMcCarran-Walter act immigration actを巡る論争で、これら民族的自己利害の主張が「同化可能性」のイデオロギーに置き換えられたことは、反対派にとっては「racism(人種主義)」の煙幕に過ぎないと受け取られた。

結局この知的伝統は、本書で検討した知的運動の猛攻の結果として倒壊し、ヨーロッパ出身諸民族の民族利害を守る中心の柱も倒壊した。

ユダヤ人知識人の非常に顕著な戦略の一つは、社会の民族基盤が全般的に損なわれるほどの radical individualism(急進的個人主義)とmoral universalism(道徳普遍主義)の促進であった。

言い換えればこれら運動は、西洋社会がすでに個人主義と道徳普遍主義のパラダイムを採用しており、自民族に対する利他的罰を行う傾向が強い点を利用した。

これら運動は、ユダヤ教を強い凝集力のあるグループベースの運動として無傷で残したまま、ヨーロッパ人に残っていたグループ凝集の源泉を弱体化させた。

この戦略の手本はフランクフルト社会研究学派の取り組みである。左翼の政治イデオロギーや精神分析家たちについても同様であろう。

端的に言えば、非ユダヤ人グループ(特にヨーロッパ系)のアイデンティティは精神病の指標とされている。

拡大血縁の衰退と個人主義の台頭にもかかわらず、ヨーロッパ人はより大きな共同体の一員としての意識を完全に放棄してはいなかった。

米国のヨーロッパ人は20世紀に入っても、人種に基づく民族感覚を保ち続けていた。

この民族感覚、人種の一員であるという意識は、ダーウィン主義の学問が支えていた。ダーウィン主義者たちは、人種間の差異を確立された科学的知見と考えただけでなく、白色人種をユニークな才能を持つ人種と考えていた。

しかし、生物学の視点で民族感覚を見出そうとするこの最後の試みは急激に衰退した。The Culture of Critiqueで論じたような知的運動の結果、今日では学界で恐怖の目で見られている。

Conclusion

西洋の個人主義社会が、ヨーロッパ起源の人々の正当な利害を守ることができるかどうか、疑わしい。

現在の傾向から言って、個人主義を放棄できないなら、最終的にはヨーロッパ人の遺伝・政治・文化影響力はかなり減少していくと予想できる。

これはパワーの前代未聞の自主放棄である。進化論者は、どこかの段階で人口の大部分がそのような自主放棄に抵抗すると予想する。

抵抗する彼らは恐らく、我々の中のよりエスノセントリックな人々であろう。

皮肉なことにこの抵抗反応は、グループに奉仕する集産主義のイデオロギーと社会組織を採用し、ユダヤ教の一面を模倣するであろう。

ヨーロッパ人の衰退が進むか止まるかに関わらず、グループ進化戦略としてのユダヤ教が西洋社会の針路を左右し続けるであろう。

引用・参考文献等は原文を参照