Decline and Empire in Ancient Rome and the Modern West: A Review of David Engels’ Le Déclin, Part 2

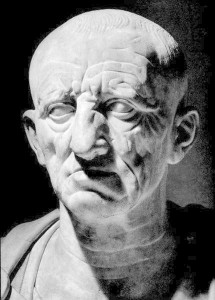

Cato the Elder

Roman Conservative & Imperial Responses

The Roman authorities, whether republican or imperial, did not passively accept these developments. Engels observes that “[f]rom the second century B.C., a large number of conservative politicians opposed with a marked traditionalism the Hellenization of the Roman elite and the Orientalization of the population” (142). This was embodied above all by Cato the Elder, who argued that Greek culture, which had become so rational, skeptical, and cosmopolitan, would mean the end of Rome:

Concerning those Greeks, son Marcus, I will speak to you more at length on the befitting occasion. I will show you the results of my own experience at Athens, and that, while it is a good plan to dip into their literature, it is not worth while to make a thorough acquaintance with it. They are a most iniquitous and intractable race, and you may take my word as the word of a prophet, when I tell you, that whenever that nation shall bestow its literature upon Rome it will mar everything. (Pliny, Natural History, 29.7)

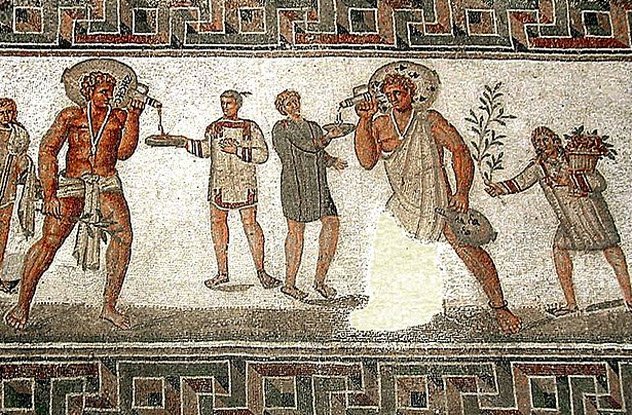

In terms of immigration, as previously mentioned, Gaius Papius had on behalf of the people apparently sought to expel non-Italic foreigners from the city altogether. Augustus later limited the emancipation of slaves, “lest they should fill the city with a promiscuous rabble; also that they should not enroll large numbers as citizens, in order that there should be a marked difference between themselves and the subject nations” (Cassius Dio, 56.33).

The Roman leadership also sought to counter native demographic decline. As early as 131 B.C., the censor Quintus Metellus Macedonicus urged making marriage mandatory. Later, “in order to ensure the biological survival of the Roman elite, Augustus . . . decreed very unpopular laws” (83), including making marriage mandatory for men between 25 and 60 and making divorce more difficult. The emperor is supposed to have justified the measures as follows:

For surely it is not your delight in a solitary existence that leads you to live without wives, nor is there one of you who either eats alone or sleeps alone; no, what you want is to have full liberty for wantonness and licentiousness. … For you see for yourselves how much more numerous you are than the married men, when you ought by this time to have provided us with as many children besides, or rather with several times your number. How otherwise can families continue? How can the State be preserved, if we neither marry nor have children? . . . And yet it is neither right nor creditable that our race should cease, and the name of Romans be blotted out with us, and the city be given over to foreigners — Greeks or even barbarians. Do we not free our slaves chiefly for the express purpose of making out of them as many citizens as possible? And do we not give our allies a share in the government in order that our numbers may increase? And do you, then, who are Romans from the beginning and claim as your ancestors the famous Marcii, the Fabii, the Quintii, the Valerii, and the Julii, do you desire that your families and names alike shall perish with you? (Cassius Dio, 56.7–8)

Tellingly, Augustus himself however was married twice and had a reputation for licentiousness. His only biological child, Julia, was notorious for her licentiousness. Read more

In his monumental tome, The History of Rome, the historian Titus Livius wrote, “There is nothing man will not attempt when great enterprises hold out the promise of great rewards,” and in the annuals of human history nowhere is this aphorism truer than when one examines the nature of Faustian Europe and its rich diversity of constituent peoples.[1] In more specific terms, and as articulated quite definitively by Prof. Ricardo Duchesne, the uniqueness of Faustian Europe lays not with its institutions, but with the primordial drive of Faustian Man to overcome all that constrains him in the eternal quest for immortal fame. [2] Returning to Titus Livy, in his history of Rome the historian was exploring not only the meteoric rise of ancient Rome, but rather attempting to ascertain the exact reasoning behind the nature of Roman hegemony. Livy’s Rome was one of transition, the historian himself being born in 64 B.C. and dying 17 A.D., and as such had lived through the tumult of the Late Republic and bore witness to Rome’s imperial rebirth under Augustus Caesar. [3] Moreover, the nature of the age that Livy had lived through was a period of “transition” not only of governmental forms, from republic to empire, but more importantly was the beginning of Roman deviation from the racio-cultural values which underpinned the Faustian nature of Europe. When European man is truest to himself, it is when he and his civilization exist in harmony with his Indo-European, Faustian nature. When deviation from this historical, dare I say cosmic reality occurs, it is a prerequisite for civilizational chaos. In the historical context of Republican Rome, it was the transition from republic to empire, and the accompanying degenerative racio-cultural changes, which deviated from the Indo-European nature of the Faustian soul of Europe, which laid the foundation for Rome’s future collapse.

In his monumental tome, The History of Rome, the historian Titus Livius wrote, “There is nothing man will not attempt when great enterprises hold out the promise of great rewards,” and in the annuals of human history nowhere is this aphorism truer than when one examines the nature of Faustian Europe and its rich diversity of constituent peoples.[1] In more specific terms, and as articulated quite definitively by Prof. Ricardo Duchesne, the uniqueness of Faustian Europe lays not with its institutions, but with the primordial drive of Faustian Man to overcome all that constrains him in the eternal quest for immortal fame. [2] Returning to Titus Livy, in his history of Rome the historian was exploring not only the meteoric rise of ancient Rome, but rather attempting to ascertain the exact reasoning behind the nature of Roman hegemony. Livy’s Rome was one of transition, the historian himself being born in 64 B.C. and dying 17 A.D., and as such had lived through the tumult of the Late Republic and bore witness to Rome’s imperial rebirth under Augustus Caesar. [3] Moreover, the nature of the age that Livy had lived through was a period of “transition” not only of governmental forms, from republic to empire, but more importantly was the beginning of Roman deviation from the racio-cultural values which underpinned the Faustian nature of Europe. When European man is truest to himself, it is when he and his civilization exist in harmony with his Indo-European, Faustian nature. When deviation from this historical, dare I say cosmic reality occurs, it is a prerequisite for civilizational chaos. In the historical context of Republican Rome, it was the transition from republic to empire, and the accompanying degenerative racio-cultural changes, which deviated from the Indo-European nature of the Faustian soul of Europe, which laid the foundation for Rome’s future collapse. Jim Penman,

Jim Penman,