Adaptive Barbarism: Politics and Kinship in the Iliad, Part 1

The following article will appear as a chapter in an upcoming book on ethnopolitical thought in ancient Greece. Constructive criticisms and comments are therefore most welcome.

We know that every organism and every species is engaged in a ceaseless struggle for survival and reproduction. This is equally true of peoples: throughout history, those with the values and genes necessary to reproduce and triumph in war prospered, the rest have already perished. I believe this basic truth is reflected in what is perhaps the most ancient sacred text to come down to us in the Western tradition: Homer’s Iliad.

If Hesiod’s genealogy of the gods portrays the primordial sex and violence at the origin of the creation, the Iliad recounts the violence of love and war at the dawn of civilization. The poet tells of a terrible war involving sexual competition for the heart of beautiful Helen, and its inevitable tragedies. But the maudlin self-pity and effeminacy of our time is unknown to Homer: if tragedy is inevitable in the human experience, the poet’s role is to give meaning and beauty to the ordeal, and to inspire men to struggle for a glorious destiny.

Homer’s portrayal of “the great leveler, war” is by no means sugar-coated. The killings of over two hundred men are individually described, dying by having their brains splattered, bladders pierced, or innards slopping out. . . . By these and so many other ways, “the swirling dark” falls before the eyes of countless men. The Iliad immortalizes the Greek variant of a wider warrior ethos: that of the Indo-Europeans — traditionally known by the more poetic name, Aryans, which I shall use — who burst forth into Europe some four thousand years ago and conquered the indigenous hunter-gatherers and farmers. The Europeans have, ever since, been profoundly influenced by the genes, languages, and martial way of life of these peoples.

The heroic values of Homer are by our standards extremely harsh, even barbaric.[1] These values however, I will show, are supremely adaptive: values of conquest, community, competition, and kinship. These reflect the spirit of the Bronze Age with its countless forgotten wars between peoples. From an evolutionary point of view, these men embraced a high-risk, high-reward strategy, with winners in battle being rewarded with great wealth, honor, and women. Their boldness and prowess indeed remain imprinted on our very genes: scientists have found that half of Europeans descend from a single Bronze Age king.

The Iliad is also worth reading to understand the ancient Greeks and the values which they lived by to survive in the brutal world of the ancient Mediterranean. Indeed, Homer’s influence over Greek culture was enormous, akin to the Bible in medieval Europe. As Bernard Knox notes, the Greeks believed the Trojan War actually occurred and was central to their national identity:

But though we may have our doubts, the Greeks of historic times who knew and loved Homer’s poem had none. For them history began with a splendid Panhellenic expedition against an Eastern foe, led by kings and including contingents from all the more than one hundred and fifty places listed in the catalogue in Book 2. History began with a war.[2]

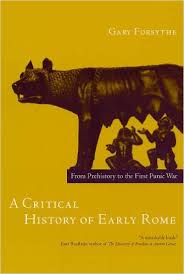

Gary Forsythe, associate professor of history at Texas Tech University, has written a critical history of the early Roman republic — critical in the sense that he casts grave doubts about a considerable amount of the received wisdom of the period. Nevertheless, the picture that remains provides a most welcome portrait of a critically important variant of the Indo-European legacy that is so central to understanding the West. The picture presented is of Rome of the republic as intensely militarized, with a non-despotic aristocratic government. Roman society during this period (509BC–264BC) permitted upward mobility and was open to incorporating recently conquered peoples into the system, with full citizenship rights. This openness continued into the later republic and the empire.

Gary Forsythe, associate professor of history at Texas Tech University, has written a critical history of the early Roman republic — critical in the sense that he casts grave doubts about a considerable amount of the received wisdom of the period. Nevertheless, the picture that remains provides a most welcome portrait of a critically important variant of the Indo-European legacy that is so central to understanding the West. The picture presented is of Rome of the republic as intensely militarized, with a non-despotic aristocratic government. Roman society during this period (509BC–264BC) permitted upward mobility and was open to incorporating recently conquered peoples into the system, with full citizenship rights. This openness continued into the later republic and the empire.