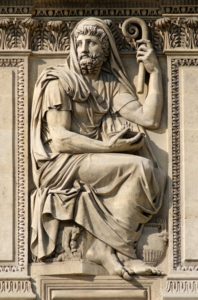

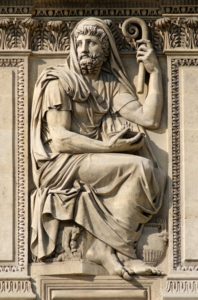

Herodotus by Jean-Guillaume Moitte, 1806. Relief on the west façade of the Cour Carrée in the Louvre Palace, Paris.

Herodotus (trans. Robin Waterfield), The Histories (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998)

In defense of history, the Roman orator Cicero once said: “To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain forever a child.” In history, we can find the past trajectory of human events and insights into the nature of human existence in other circumstances, two powerful guides for the future. The first historian was Herodotus, a Greek who lived some 2,500 years ago. His massive Histories are an encyclopedic snapshot of that epoch, an enormous collection of stories on all the nations of the known world which he had gathered during his travels.

Herodotus is a perceptive observer of human nature. His humans are indeed riven with contradictions and subject to extreme pressures, torn between often-conflicting personal, familial, and political loyalties. Herodotus’ is a world of sex and violence, of tribes and cultures. Reading Herodotus remains a rewarding experience, for our human nature has not changed much over the past 2,500 years. I propose an evolutionary analysis of the Histories, highlighting in particular the complex and dynamic relationship between environment, culture, and ethnicity. As we shall see, national identity, ethnocentrism, and the condemnation of decadence — what we would call maladaptive culture — are major themes in Herodotus’ work.

The known world of Herodotus can be seen as a kind of enormous grid centered upon the eastern Mediterranean, where most of the Greeks lived, and the Persian empire, by far the largest and most powerful state of the time. In this vast world, the Greeks were a young people scattered across the Mediterranean “like frogs around a pond” (Plato, Phaedo, 109b). The Greeks were well aware of the other great and often mysterious peoples around them: the Semitic trading-nation of Phoenicia in the Levant, the wild nomadic Scythians in the north, the mysterious Ethiopians in the south and Indians in the east, the massive city of Babylon in Mesopotamia, and the venerable Egyptians, among others.

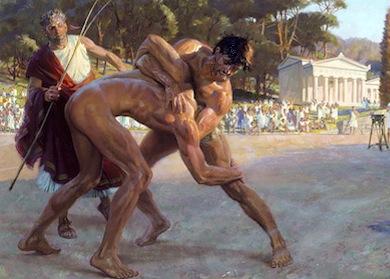

Herodotus’ world certainly featured peaceful commerce, cultural exchange, and ethnic intermarriage among these peoples — the historian is quite broad-minded and free of chauvinism in this respect.[1] But, as Herodotus makes clear, this was also a world of extreme ethnocentrism and brutal wars. The highly diverse material of the Histories, which features myths, stories, and ethnographic portraits of the many peoples of the known world, is united around the rise and decline of the Persian empire: each people is described when they encounter the Persians, the latter being invariably bent on conquest. The work climaxes with the great struggle of an unlikely coalition of Greek city-states led by Athens and Sparta and their ultimate triumph over the Persian invaders. Meditation on war and commemoration of Greek unity and freedom are thus at the center of Herodotus’ narrative. (Incidentally, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that many of the most iconic lines and scenes in the otherwise unrealistic film 300 are actually directly drawn from Herodotus.) Read more

Faustian Man in a Multicultural Age

Faustian Man in a Multicultural Age