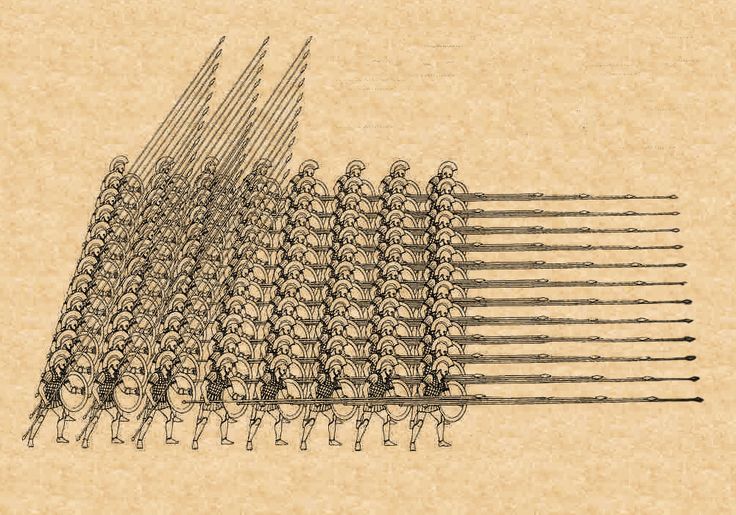

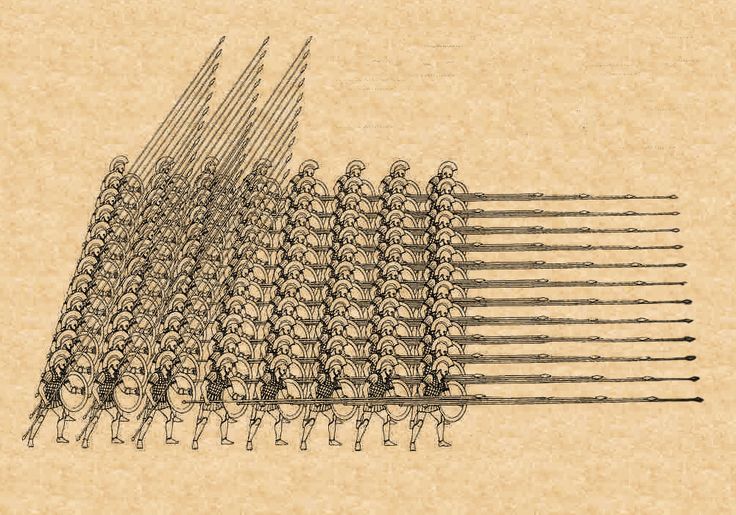

Greek hoplite citizen-soldiers in phalanx formation

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from a longer article on Herodotus’s account of the Greek-Persian wars. The entire article will appear in the Summer issue of The Occidental Quarterly.

There was undeniably a strong feeling of shared national and cultural identity among the Greeks. However, if one looks at the sweep of ancient Greek history, one is struck by the disconnect between the pervasive rhetoric expressing pan-Hellenic sentiment and the political reality of division and often brutal wars among Greeks. The demand of the polis for total loyalty from its citizens meant that there were few qualms about annihilating fellow Greeks, if this was in the city’s immediate interests. Furthermore, it is often difficult to determine the degree to which patriotic sentiment actually underpinned the Greek states’ resistance, as opposed to merely being eloquent rationalizations for narrowly political interests, such as Athens and Sparta’s desire not to be dominated by any foreign power, Greek or not. Indeed, Herodotus says that one city, Phocia, opportunistically sided with the allies purely because its traditional enemy, Thessalia, sided with the Persians. (8.30) The collaboration of individual politicians[1] and cities with the Persians was common. Indeed the city of Delphi itself became Medized. In short, as so often in our history, broader ethnic and civilizational interests were ignored in the face of the selfish political interests.

In the Persian Wars, the Greek allies certainly achieved sufficient unity to ultimately repulse the invaders, but one is struck at how tenuous that unity was and how exceptional even that degree of unity was in the course of Greek history. The allies, who called themselves simply “the Greeks,” in the end only made up about one-in-ten continental Greek cities, the rest remaining neutral or collaborating.

Though far less discussed than the polis, the Greeks did have a quite venerable tradition of federalism—i.e., forming leagues of city-states. Such leagues, typically combining joint temples, a common council, arbitration, military alliance, and coinage, with greater or lesser degrees of central authority—were a common feature in Greek political history. Shared ethno-regional identity was a common basis for the formation of such leagues, as in Arcadia, Boeotia, Crete, and Ionia. Athens and Sparta would, in their history, each lead their own military alliances as hegemonic cities.

The league projected the basic features of the familial religion beyond the city to a regional commonwealth: shared blood and gods sealed the alliance of cities in a league, including notably a shared holy sanctuary, just as the family household and the polis were sacred spaces. However, the league was typically not a true federal state or sovereign federation, but a coalition of cities, each with its own army and jealous of its civic sovereignty. The confederal league therefore never had the solidity of the polis. The various leagues tended to fluctuate in their effectiveness as the necessity of unity (typically to acquire military scale) was in constant tension with the centrifugal tendency of each city’s desire for autonomy. In practice, a league tended to do well if it had a hegemonic city which could impose decisive leadership or, if led by two cities, if these leader-cities were in basic agreement. Rebellion and subjugation of cities was common. The Greek leagues failed to scale beyond the region and it is not surprising that they eventually fell to the far larger powers of Macedon and the Roman Empire. The ancient Greek leagues in their fragility were not unlike later fractious confederations of sovereigns, such as the Hanseatic League, the antebellum United States, the German Confederation, or the European Union.

Given the fragility of the league, moderns will be less surprised to learn that despite the Greeks’ strong sense of identity, it rarely occurred to them to seek to achieve political unity. This was not so much due to lack of imagination—Plato and Isocrates did make concrete proposals for Greek unity at the expense of barbarians—but due to the sheer impracticalities of federalism in an age before telecommunications. In the premodern world, as Montesquieu later remarked, scale was only possible for monarchies, not for republics.[2] Read more

Mika Ojakangas, On the Origins of Greek Biopolitics: A Reinterpretation of the History of Biopower

Mika Ojakangas, On the Origins of Greek Biopolitics: A Reinterpretation of the History of Biopower