Warrior-Hero of the West: Erich Hartmann, the Blond Knight of Germany

Erich Hartmann was not a figure of world-historical importance, striding across the earth like a colossus. He was not a statesman or conqueror, nor a paradigm-destroying scientist, nor a virtuoso writer moving the masses. He was a simple airman of the Second World War. Yet, the way he performed his duty, with courage and honor—and deadly efficiency—made him the highest scoring ace in history and one of the genuine heroes of Western history. Erich Hartmann is a splendid example of the qualities peculiar to Western Faustian man, such as an acute sense of individuality, iron willpower, and utmost daring. For a few moments let us leave this modern world with its depressing role models, and look back in time to feast our hearts on the story of a great man, full of character and intelligence, a man whose greatest triumph ironically came after the fighting had ended.

Early Life

Hartmann was born April 19, 1922, in Wűrttemberg, Germany, in the heart of Swabia, a region renowned for its hardheaded, frugal, inventive, and proud people, whose number also includes Hegel and Erwin Rommel. Erich’s father Alfred was a doctor with a broad outlook on life, and his mother Elisabeth was capable, adventurous and beautiful. She apparently gave Erich his very blonde hair—and a daring spirit.

Young Erich was an excellent and fearless athlete. He commented humorously much later that his father thought he was “a kind of dare-devil, or an idiot” (Heaton and Lewis 9). His father wanted his boys to become doctors, and Erich assumed he would eventually follow that line, but really he just wanted to fly. From an early age he dreamed of emulating the aces of the Great War. His mother also wanted to fly, so she earned a pilot’s license and took her two sons flying with her. Later the family started a glider club and Erich was in his element: the air.

Erich went through school without enthusiasm, but passed his courses without difficulty. When he was seventeen he spied the future love of his life: Ursula Paetsch. He pursued her single-mindedly, going so far as to pummel a rival, and won her over with his customary directness, sparking a lifelong love affair.

Erich was blessed with an admirable character. (Actually, since people build their characters from the choices of their free wills, Hartmann was responsible for his own character, which is more virtuous. Temperament or natural disposition is what people get naturally; character is formed.) His biographer Raymond Toliver describes Erich as highly intelligent, with a will “almost fierce in its drive to prevail and conquer” and says he was “an incorrigible individualist in an age of mass . . . conformity.” Hartmann, he continues, had a blunt style of honesty that often mounted to a “devastating” lack of tact. Finally, Hartmann possessed “consummate coolness under stress” (Toliver and Constable 5, 12). All this corresponds very well with the characteristics possessed by Western Faustian man as described by, among others, Ricardo Duchesne. Read more

Mika Ojakangas, On the Origins of Greek Biopolitics: A Reinterpretation of the History of Biopower

Mika Ojakangas, On the Origins of Greek Biopolitics: A Reinterpretation of the History of Biopower

Dissident Dispatches: An Alt-Right Guide to Christian Theology

Dissident Dispatches: An Alt-Right Guide to Christian Theology

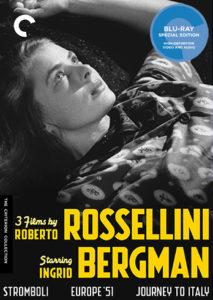

One early evening when we went to the Paramount to go to the movie, there were eight or ten people with picket signs marching back and forth in front of the theater—don’t go to this movie. I didn’t catch on to the details, but I knew it had to do with the actress Ingrid Bergman, who was starring in the movie and very big at the time—Casablanca, etc.—doing something really bad. What it was, I later found out, was she had had an illegitimate child with the film director Roberto Rossellini;

One early evening when we went to the Paramount to go to the movie, there were eight or ten people with picket signs marching back and forth in front of the theater—don’t go to this movie. I didn’t catch on to the details, but I knew it had to do with the actress Ingrid Bergman, who was starring in the movie and very big at the time—Casablanca, etc.—doing something really bad. What it was, I later found out, was she had had an illegitimate child with the film director Roberto Rossellini;