The Problematic History of the European Union: Review of ‘Eurowhiteness’

/3 Comments/in Anti-White Attitudes, Featured Articles/by Jason Cannon

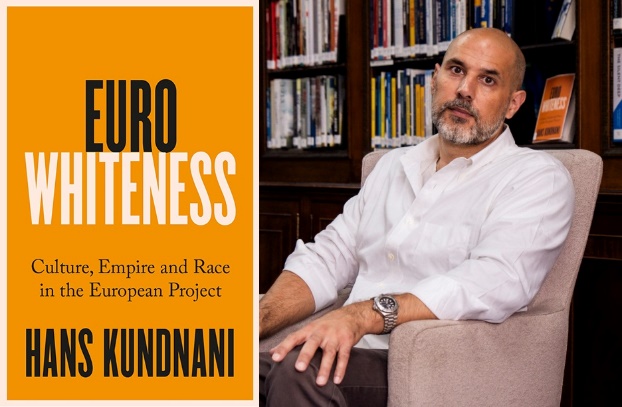

Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project

Hans Kundnani

Hurst Publishers, 2023

Eurowhiteness is one of those books that immediately catches the attention of a “racist”. With a bright orange cover and a title like Eurowhiteness displayed in large block letters, how could it not? Curiosity compelled me to take it down from the bookshop shelf and browse the introductory remarks. After a brief Google search to confirm my suspicions of the mixed-race origins of the author, I was ready to groan and roll my eyes at what I presumed to be a vapid book that deconstructed European identity by arguing that “blackness” or “brownness” somehow has just as much place within Europe as “whiteness.” What emerged from its pages instead was a novel left-wing polemic against the European Union (EU) *because* of its perceived Whiteness.

Author Hans Kundnani was born to an Indian father and a Dutch mother and grew up in the United Kingdom. As with most mixed-race people who struggle to place their identity, he believes this background gives him a unique perspective on European history and identity. His first post-university job was for the Commission for Racial Equality, the enforcement body established by the UK Race Relations Act 1976, and by 2009 he was working for the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank dedicated to Pan-European ideas. As Kundnani describes it, Eurowhiteness is the culmination of his shift in thinking from a pro-European convinced of the moral good of the EU, to a critic who has abandoned the myths that once informed his worldview.[1]

Kundnani does not present a bibliography, but his ideological debt to leading thinkers in critical race and post-colonial theory is apparent. His endnotes draw from well-known figures in this sphere such as Charles W. Mills, Gurminder K. Bhambra, Paul Gilroy, and historical forebears Frantz Fanon and W.E.B Du Bois. The acknowledgements section reveals Kundnani’s “particular debt” to Swedish post-colonial scholar Peo Hansen. Hansens’ book Eurafrica, which explores the African strategic fantasies of early Pan-European thinkers — notably Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi — are what seemingly began Kundnani’s path towards euroscepticism.

Eurowhiteness is well-paced and I can offer no criticism of Kundnani’s cogent writing style. Other reviewers have affixed the word “challenging” to the book, but to those of us not inflicted with colour-blind thinking and who already see the intrinsic link between Western civilisation and the White race, the themes parsed out in Kundnani’s book are hardly cause for discomfort. His claim that the EU has recently taken a “civilisational turn” towards the protection of European identity and that as a result the institution could just as easily be used as a vehicle for racist purposes is also familiar. Way back in 2017 Richard Spencer was pouring cold water on the euphoria over the Brexit vote, arguing that the European Union could instead become a potential racial empire, a counter to NATO and Atlanticism.

The value of this book for readers of The Occidental Observer lies principally in understanding the intellectual journey of the author and discerning the potential for the emergence of a popular left-wing critique of the EU in the Anglosphere and beyond. Kundnani’s transition from EU booster to EU sceptic is instructive, as well as revealing the anti-White perspectives and motivations that can lie behind soft-spoken academics. Despite the myriad of anti-racist measures, tolerance initiatives, and hate speech laws that encompass the modern EU, Kundnani has turned on the European Union because it is just still too White, too Western. After all, the EU’s history is rooted in Europe and much of its historical and present-day motivations are the defence of European people and Western values. That alone is enough to condemn it in Kundnani’s eyes.

Regionalist Racism

Kundnani’s critique of the European Union begins with the dismantling of what he sees is the common misunderstanding of its structural nature. Rather than conceptualising it as an inclusive cosmopolitan project that has renounced nationalism — a position held by both supporters on the left and critics on the right — Kundnani attacks the EU as a project analogous to nationalism. According to Kundnani, it is better understood as a form of “regionalism.” That is, nationalism on a more continental scale, and imbued with all the same chauvinistic impulses, power dynamics and histories of colonial dispossession that nation-states are saddled with.[2] The same impulse towards nation-building is found in the ‘region-building’ of the EU.

Building on this concept of regionalism as nationalism on a larger scale, Kundnani draws upon Jewish academic Hans Kohn’s theory of nationalism. Kohn invented the concept of civic nationalism as distinct from ethnic nationalism ideally suited for facilitating non-White migration. Just as a nation can have strands of civic and ethnic nationalism, so too does the regionalist EU. It possesses both a civic and an ethnic component that waxes and wanes in strength across time; secularism, civil institutions and liberal rights weighed against Christian, illiberal, civilisational and racial ideas. For Kundnani, it is “disturbing” that the EU continues to draw upon such ethnic/cultural elements from Europe’s history.[3]

Chapter 2 briefly traces the history of European identity from its ethnic and cultural origins at the time of the Battle of Tours, where the word was first used by the victorious Franks in order to “other” the external enemy, the Muslims. From the seventeenth century onwards, ideas of Europe began to shift from being strictly synonymous with Christianity. At this point, a rationalist, enlightenment notion of Europe with a civilising mission to the rest of the world emerged, and finally the notion of whiteness or the racial identification of the European peoples as Whites.

Kundnani’s critique of the Enlightenment values that form the basis of the EU follows the now standard deconstruction of its universalism, positing that it is instead of being based in Whiteness and in the particular systems of White supremacy:

… while Enlightenment ideas like the “rights of man” — the antecedent of what we would today call “human rights” — were potentially universal, they emerged from a particular European context, and moreover, were put into practice in a racialized way. … [C]olonialism and slavery were carried out in the name of enlightenment ideas.[4]

The Enlightenment is presented (or problematised, to use the lingo) in the most debased terms possible, as the output of White supremacists. Immanuel Kant, whom Kundnani points out wrote an early appeal for European unity that is now celebrated by the EU, is lambasted for his racial theories. Rousseau is condemned because his writings did not speak directly to the plight of Black slaves in French colonies.

Next, the alleged colonial origins of the EU are fleshed out — the “original sin” of the EU as Kundnani likes to call it. Rather than being anti-colonial, the early movements towards Pan-European unity developed the concept of Eurafrica, which envisioned the African continent as a yet undeveloped source of raw material for a future European power-bloc. Many of the founding states of the EU also held onto their colonial possessions after the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the formal precursor to the EU. France and Belgium in particular factored these colonies into their economic considerations for a post-war redevelopment enmeshed into wider Europe. Predatory relations further continued after the formal independence of these colonies, in the form of exploitative labour schemes and guest worker programs.

Kundnani argues that from 1945 onwards, civic regionalism came to dominate as a reaction to the ethnic conflicts of World War II. This was not the clean break from Europe’s past that many claimed it to be, with the older ethnic/cultural regionalist tendencies still pushing through into Pan-European rhetoric. The civilising mission remained, as did the belief in the superiority of European values and the claim of their universality. Even the holocaust is not spared from critique. The EU, Kundnani contends, has used holocaust remembrance as a cover for forgetting colonial injustices, patting themselves on the back for upholding “Never Again” whilst continuing to refuse to engage in decolonisation or recognise Europe’s true original sin. The foundational memory of the holocaust has obscured Europe’s foundational history of colonialism, and thus the EU is a project of political amnesia that has forgotten, or choses to ignore, its origins as a quasi-colonial institution.[5]

The end of the Cold War reignited the civilising mission towards incorporating the EU’s more “backward” eastern Europeans neighbours, those who were European but not quite yet *in* Europe in cultural or political terms. More than halfway through the book, we finally encounter the meaning behind its title, derived from Hungarian sociologist József Böröcz, who proposed a spectrum of Whiteness within Europe. “Eurowhitness” is associated with the centre of Europe in the West and “dirty whiteness”, the less immaculate and somewhat less West European version to the East. Kundnani repurposes the term to refer to the ethnic/cultural version of European regionalist identity. Eurowhiteness, used as a pejorative or a negative by Kundnani, simply means to identify as European in a non-civic (that is, “racist”) way.

With the arrival of the Eurozone crisis in 2010 and the chaos of the refugee influx of 2015, Kundnani argues that the European Union has swung towards a defensive position, focused on countering the external threats to the stability of Europe:

By the beginning of the 2020s, the civic element of European regionalism seemed to have become less influential and the ethnic/cultural element more influential in “pro-European” thinking. In other words, whiteness seemed to be becoming more central to the European project.[6]

Kundnani sees little distinction between pro-European politicians who posit a defence of the “European Way of Life” or who worry about the future of Western civilisation and far right “extremists” who invoke the supposed trope of the great replacement. In the face of these threats to EU stability, those who fear the decline of EU power and sovereignty are the international political equivalents of the those who fear White replacement.[7] After all, both positions are “pro-European.” For Kundnani, the EU’s dramatic response to the war in Ukraine, opening its arms wide for Ukrainian refugees compared to what he sees is the closed-door policy to non-White refugees at its southern borders, is just further proof of the return to Eurowhiteness.

By far the weakest point of the argument is the evidence (or general lack thereof) provided to attribute Eurowhiteness motivations to current EU leaders or bureaucrats. As an outsider, the civic European component still seems predominant and the appeals to European civilisation are mere scraps thrown to a public increasingly disillusioned by the failure of the EU to respond to issues of mass immigration. It feels like a stretch to widely attribute chauvinistic views to the EU leadership, but the impulse to defend Europe as Europe, as some kind of distinct entity of a distinct group of people, does certainly exist enough for the label of Eurowhiteness to stick.

Kundnani believes that a different Europe is needed than the one we currently have.[8] Nearing the conclusion, he briefly hints at the EU itself being a barrier to overcoming Eurowhiteness. He claims that engaging with its colonial past could in fact be a danger to the EU because Eastern European member states with no colonial history or collective guilt over colonialism would resist such initiatives, which could in turn have a disintegrative effect on European identify and the structure of the EU. However, the narrative abruptly ends there and is not further expounded upon, and we are left wondering what his true feelings about the future of the EU are. Kundnani at least admits in the introduction that he is only offering critiques, not solutions — at least not for the EU.

Reconsidering Brexit

The final chapter, Brexit and Imperial Amnesia, changes gears and presents us with a revisionist account of the Brexit Referendum, aimed at the British left still reeling from the 2016 vote. Kundnani challenges the dominant narrative of the Leave vote as a racist vote yearning for a White fortress that shuts the door to migrants. The true nature of the Brexit vote is presented as more complex and less binary, highlighting that one in three members of Britian’s ethnic minority population also voted to leave. Kundnani expands upon the angst of many non-White Britons regarding the EU and their perception that continental Europe is still more racist than the UK. Given the persistence of Eurowhiteness, it remained hard for Britain’s Black and Asian populations to truly feel part of the European project and they have struggled to identify with its history. Kundnani is also captive of these feeling towards the EU, mentioning in the introduction that he could never bring himself to feel “100% European” due to his mixed-race background.[9]

Another area of hostility outlined towards the EU is the discrimination many felt from the changes that entrance into the project brought to immigration. Following the admission of the UK into the EEC, Commonwealth citizens from Britain’s former colonies suddenly found it was harder to enter the UK than continental Europeans. The story is familiar to Australians, who too felt abandoned by the mother country when the border control lines at the airport no longer privileged the peoples of New Brittania.

With the Brexit vote reconceptualised, the Leave decision is transformed into an opportunity, offering the chance for Britain to rebalance its identity. Eurowhiteness and ties to the EU have allowed the UK to escape from its colonial history by focusing on the national identity narratives of Europe and World War II. Through engagement with former colonies, Britain can shift its national story away from Europe. Here, in the final two paragraphs of the book, we finally come to the vehicle of this reimagining of Britain and what perhaps Kundnani sees as the best way to combat Eurowhiteness: immigration policy.

The corrective is a policy which amends the turn away from Commonwealth-based immigration — a form of reparations issued on the path to becoming a less Eurocentric country:

It would be possible to go further in the rebalancing of British immigration policy that has taken place since Brexit — in particular, by making it easier for citizens of Britain’s former colonies to come to the UK. … such a policy — what might be called “post-imperial preference” — could even be thought of as a form of reparations.[10]

Once again, the great replacement trope is an evil conspiracy theory when observed by a critic and an obvious political good when advocated for by a supporter.

Yes. And?

Kundnani’s thesis can be pulled apart on a number of technical levels. The appropriateness of the notion of regionalism as applied to the EU and its analogy to nationalism can be questioned, and in turn there is often a conflation of concepts, with “Europe”, “the European Union” and “EU Member states” used interchangeably as suits his argument. A rather weak critique of neoliberalism also flows underneath the main critique of Eurowhiteness and the linkage between the EU and colonialism feels forced. By the time the EEC came along in the 1950s, European colonialism was in its death throes, far from the height of its power. However, lacking a detailed understanding of the history and functioning of the EU and of the political conceptions of its leadership class, my review of the narrative of Eurowhiteness turns elsewhere.

Much of the book is perplexing if you don’t have a pathological sense of White guilt or an inferiority complex about the success of European civilization. This is without a doubt a book produced from decades spent ensconced in an academic world brimming with anti-White narratives, plundering the rancid depths of post-colonial theory for a vector to attack an institution that even most die-hard progressives support — until they read Kundnani’s book perhaps. The extent of White guilt that a reader must have to agree with his conclusions is altogether frightening when considering that the book has received a generally positive response in the British left-wing press.

To me, the arguments presented in the book elicited a kind of “Yes. And?” reaction, a sense of confusion or bemusement as to why a historical fact or a political reality has been presented as a negative. Kundnani considers it damning evidence of Eurowhiteness that the EU draws upon figures such as Charlemagne and continues to award the Charlemagne Prize in his name. Why is this damning? Because he is European? At its heart, Kundnani’s critique is that the European Union only brings together European nations and peoples, European ideas and values, and strives for European interests and goals. Yes. And? Is this a bad thing? Are Europeans not allowed to do this? The EU was certainly never constituted in any way other than as a continental union, no different than similar unions that now exist in the other regions of the world. The fact that some of the original member states still possessed leftover colonial territories is beside the point.

It is hard to shake the feeling that Kundnani feels there is something inherently dangerous with the European Union setting its geographic limits as Europe and bringing Europeans together. The flat refusal issued to Morocco’s request to join the EEC in 1987 is transformed by Kundnani from an obvious rejection issued to a country trying to simply cash in on proximity to Europe into proof of a malign identity embedded within the EU. Does Kundnani think it was wrong to reject Morrocco’s application? As a country with a long historical link to the African continent, would Spain being rejected from joining the African Union also be couched in such negative framing?

A Union, if you can keep it

Eurowhiteness raises questions regarding the long-term durability of the EU project. If the demographic trends away from a White majority in European nations continue, will we start to see more Euroscepticism from the left, more anti-White reactions against the EU like that which has captivated Kundnani? Whilst it would be comforting to believe that Eurowhiteness is an isolated product of the distinctly British detachment from the EU that has no currency elsewhere, Kundnani draws upon a global range of anti-EU perspectives, both historical and current-day. It’s not hard to see conclusions such as his, presented in an accessible form, from developing in popularity.

Non-whites living in the West have stepped up their rhetoric in recent years, rallying against the presence of White faces and White ideas within their living spaces. Statues have been removed, the Western canon expunged, and names of places and institutions changed for the sake of diversity and anti-racism. Their actions have shown that they believe that all Eurocentric ideas must be challenged, and above all that diverse faces must be predominant in public life. To a degree it is surprising that critiques of the EU along these lines have not emerged before to a significant degree. Perhaps that is simply due to the political left adopting a reflexive pro-EU stance in the face of the right-wing anti-EU stance —a reflexive response that Kundnani is now seeking to correct.

Ultimately, the impulse behind Eurowhiteness is a sense of exclusion by Europe and a feeling of discomfort in Western civilisation, one certainly shared by others of non-European background. Kundnani admits as much himself when he states that: “European identity is externally exclusive — that is, it excludes those who are not European or who cannot think of themselves as being European.[11]” To those of us comfortable with European identity, Charles Martel or Charlemagne are inspirational warriors of our history, men who shaped and fought for the Europe we have and cherish today and without whom we may not even exist.

The Battle of Tours in October 732 — by Charles de Steuben (1788–1856)

All that people like Kundnani seem to see are exclusionary figures who upheld Christendom or who waged wars to defend Europe from dark-skinned Muslims — detestable characters they cannot feel an affinity with and whom they believe only a racist would celebrate. They survey the history of Europe and all the cultural touchpoints behind the EU and find that it just doesn’t represent them. From a racialist perspective, they cannot really be faulted for this. It is a natural impulse to seek out the familiar and to desire to live in an environment that accords with your being and your own racial identity. The problem was always in letting them into the West in the first place.

In all, Kundnani’s polemic against the EU reads as a fear of White unity writ large. Whiteness (or Eurowhiteness) is the threat to overcome. That much is clear when he advocates for non-White immigration as the solution to Britain extracting itself from Eurocentrism and frets about the possibility of the far-right moderating its Euroscepticism and accepting the EU[12].

The center right, it turns out, doesn’t have a problem with the far right. It just has a problem with those who defy E.U. institutions and positions. …

The blurring of boundaries between the center right and the far right is not always as easy to spot as it is in the United States. …

[T]oday’s far right speaks not only on behalf of the nation but also on behalf of Europe. It has a civilizational vision of a white, Christian Europe that is menaced by outsiders, especially Muslims. …

But as the union unites around defending a threatened European civilization and rejecting nonwhite immigration, we need to think again about whether it truly is a force for good.

Any form of White identity, and any association of Whites together as Whites, even if only implicit, must necessarily be a dangerous thing. As Eurowhiteness proves, even Western institutions that we may have once considered safe by virtue of being perceived as progressive are now suspect.

[1] By his own admission this did not however cause him to vote Leave in the Brexit referendum of 2016, presumably because it still felt racist to do so

[2] At this point, Kundnani posits the Marxist theory of nationalism (Hobsbawm, etc.), which claims that national identities only emerged during the Enlightenment era, but it doesn’t impact the argument much.

[3] Kundnani, H 2023, Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project, Hurst & Company, London, 42.

[4] Ibid., p.53—55

[5] For all the complaints about European universality or that “Europe is not the world”, Kundnani conveniently fails to mention the empires and colonial histories of the non-European world, which were every bit as exploitative and arguably more barbaric.

[6] Kundnani, Op. Cit., p.126

[7] Ibid., p.146

[8] Ibid., p.3

[9] Ibid., p.1

[10] Ibid., p.178

[11] Ibid., p.20

[12] Kundnani, H 2023, ‘Europe may be headed for something unthinkable’, New York Times, December 13, retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/13/opinion/european-union-far-right.html

Miracles of Migration: From Mechanical Marvels to Malevolents with Machetes

/20 Comments/in Anti-White Attitudes, Featured Articles/by Tobias LangdonThe Welshman Aled Jones (born 1970) did something remarkable as a boy. He enchanted and astonished millions with the purity of his voice and depth of his musical talent. After that, he grew up and deservedly became a rich media star. Then he himself met a remarkable boy. Back in the 1980s, Jones had been remarkable in a White way. The boy he met in London in 2023 was remarkable in a non-White way:

A machete-wielding teenager who threatened to cut off singer Aled Jones’s head as he robbed him of his £17,000 Rolex watch has been detained. The Welsh baritone was attacked by the 16-year-old boy on Chiswick High Road, west London, on 7 July [2023].

The teenager pointed a machete in his face and told him to remove the watch, Ealing Magistrates’ Court heard. He was given a 24-month detention and training order after admitting robbery and possession of an offensive weapon. Vijay Khuttan, prosecuting, told the court Mr Jones and his son were out for a walk when they were “spotted” by the youth who had seen the high-value watch on his arm. “He crossed the road and followed them down the high street,” Mr Khuttan continued. “He pulled out a machete and ran towards Jones and his son with the machete brandished.”

The youth told Mr Jones: “Give me your Rolex or I will cut your arm off,” the prosecutor said, adding that the defendant then pointed the machete in the singer’s face. When the teenager noticed Mr Jones was still following him from a distance, he told him to “walk the other way or I will cut your head off”. … The court heard the teenager had previously stolen a gold Rolex watch worth £20,000 from a man in his 70s at Paddington railway station.

Chairman of the bench Rex Da Rocha told the teenager his record was “appalling”, adding: “Pointing that machete at an innocent person is totally unacceptable.” (“Aled Jones: Boy who threatened singer with machete detained,” BBC News, 3rd October 2023)

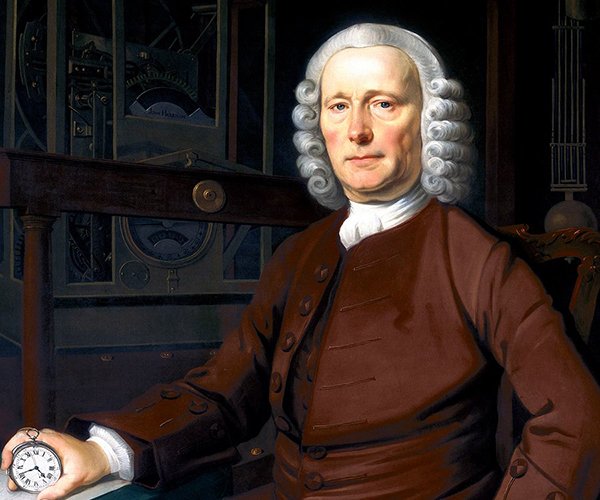

Mechanical marvel: an 18th-century timepiece by the Yorkshire genius John Harrison (image from Wikipedia)

That vibrant vignette from 21st-century Britain was reported by the BBC, but the BBC didn’t, of course, point out its deep racial significance. However, it wasn’t just a case of a talented White musician being robbed by a predatory non-White psychopath. It was an encounter between White civilization and non-White savagery, between a race capable of ascending the greatest heights and a race capable of plumbing the worst depths. Aled Jones had ascended to the greatest heights of culture in his singing and love of classical music. The watch he was wearing represented the greatest heights of technology and ingenuity. That’s why it was so valuable and prestigious. And that’s why the non-White robber — almost certainly a Black — was ready to plumb the depths of savagery for possession of it.

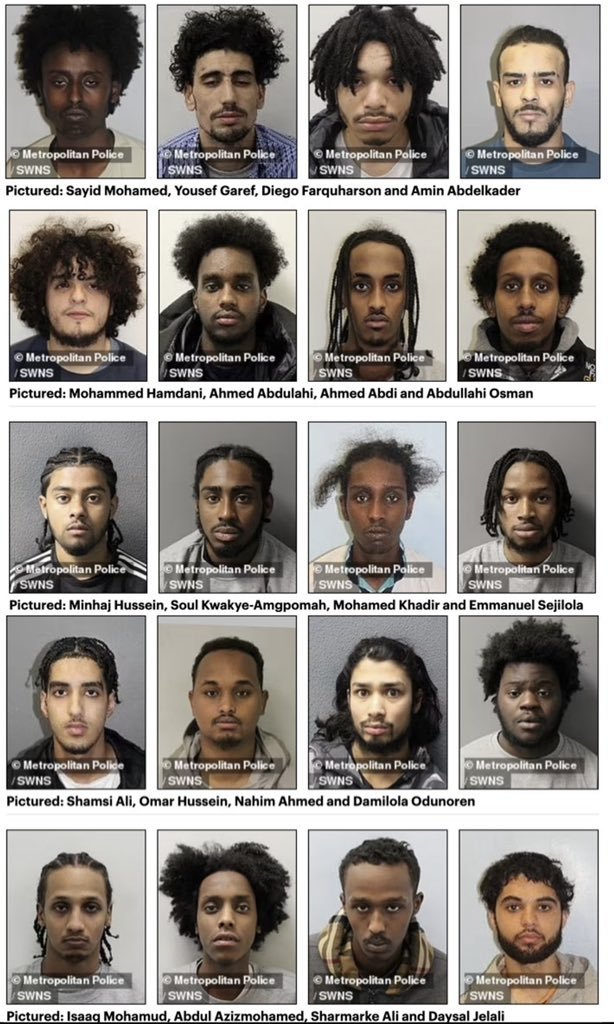

Malevolents with machetes: the Rolex-rippers who contribute Black savagery to White civilization

Malevolents with machetes: the Rolex-rippers who contribute Black savagery to White civilization

What Blacks don’t have the brains to build, they certainly have the savagery to steal. The London Metropolitan Police have recently conducted an undercover operation against the theft of expensive watches by so-called “Rolex-rippers.” They have now issued photos of all the criminals old enough to be publicly identified. It’s a miracle of migration that almost all are Black and that most have obviously Muslim names. On their own, Blacks in Africa never even invented the wheel, let alone any true kind of machinery. The Jewish scientist Jared Diamond (born 1937) attributes this Black failure to purely bio-geographical factors in his Pulitzer-prize-winning best-seller Guns, Germs and Steel (1997). After all, according to leftists like Diamond, race does not exist and Blacks are just as capable of high intellectual achievement as anyone else. Therefore we must explain Africa’s failure by something external to Blacks — their natural environment. It couldn’t possibly be anything to do with Black evolution or genetics.

Black genius stymied by Mother Nature

That’s what Diamond claims. He says he’s interested in revealing the truth and removing unfounded prejudices. I don’t believe him. As I explained in my article “Destroy the Goy: The Metaphysics of Anti-White Hatred,” I think he’s really interested in concealing the truth and denigrating Whites. I think Diamond’s primary motive is goyophobia, or hatred of White Europeans. When he tries to explain why Europe conquered Africa rather vice versa, he obviously derives great satisfaction from the alternate history of militarily superior Africans conquering Europe:

All of Africa’s mammalian domesticates — cattle, sheep, goats, horses, even dogs — entered sub-Saharan Africa from the north, from Eurasia or North Africa. At first that seems astonishing, since we now think of Africa as the continent of big wild animals. In fact, none of those famous big wild mammal species of Africa proved domesticable [this isn’t true]. They were all unqualified by one or another problem such as: unsuitable social organization; intractable behaviour; slow growth-rate, and so on. Just think what the course of world history would have been like if Africa’s rhinos and hippos had lent themselves to domestication! If it had been possible, African cavalry mounted on rhinos or hippos would have made mincemeat of European cavalry mounted on horses. But it couldn’t happen. (Why Did Human History Unfold Differently on Different Continents for the Past 13,000 Years?)

You can see the same goyophobia in Guns, Germs and Steel when Diamond presents the alternate history of “bedraggled” Spaniards being “driven into the sea” by Aztec cavalry:

That’s an enormous set of differences between Eurasian and Native American societies — due largely to the Late Pleistocene extinction (extermination?) of most of North and South America’s former big wild mammal species. If it had not been for those extinctions, modern history might have taken a different course. When Cortes and his bedraggled adventurers landed on the Mexican coast in 1519, they might have been driven into the sea by thousands of Aztec cavalry mounted on domesticated native American horses. Instead of the Aztecs dying of smallpox, the Spaniards might have been wiped out by American germs transmitted by disease-resistant Aztecs. American civilizations resting on animal power might have been sending their own conquistadores to ravage Europe. But those hypothetical outcomes were foreclosed by mammal extinctions thousands of years earlier. (Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies [1997], ch. 18)

Kevin MacDonald has described seeing Diamond in full anti-White flow: “I went to a talk by Diamond at a large packed lecture hall at Cal Tech in the early 2000s. When he gleefully fantasized about Africa conquering Europe, the crowd burst into applause. Being a reasonably respectable academic at the time, it was a good introduction to the anti-White hatred that boils just below the surface of the moralistic rhetoric of anti-racism.” But Diamond’s goyophobia is illogical by his own principles. There is no room for moralism or the unique malevolence of Whites in the “All by Accident” school of history. If all human groups are equal in moral and intellectual potential, then no group can be superior or inferior, more virtuous or less evil. Consequently, human history must be explained by the chance factors of biogeography.

The hidden aims of anti-racism

Indeed, Diamond’s thesis or something like it follows with inexorable logic from the fundamental axiom of anti-racism. If race does not exist and we are all the same under the skin, differences between human groups must arise from external factors beyond human control and not susceptible to moral judgment. If the historical dice had rolled another way, then Blacks would have enslaved Whites and Jews would have committed genocide against Germans. Victims in our time-stream are villains in an alternate time-stream, and villains are victims. Who oppresses whom is entirely a matter of chance and historical contingency. There is no other logical conclusion.

But anti-racists don’t reach that conclusion, because the ideology of anti-racism does not obey logic. Anti-racists follow their fundamental axiom only so far as it suits them. Although they claim that all human groups have equal potential, they blame the failure of non-Whites on Whites without any mention of chance or historical contingency. Rational anti-racism would be a much more sober and much less ambitious ideology than anti-racism as it presently exists. Rational anti-racism would not be strident or self-righteous, and it would not seek to bully, brow-beat or instil guilt in Whites. In short, it wouldn’t deliver what anti-racists really want: power, privilege and revenge.

Roche’s revenge

And self-proclaimed anti-racists take revenge precisely by importing non-Whites into the West. Some of the Black faces and names in the police photos above are obviously Somali or from closely related groups. But why does Britain have so many predatory Somalis living on its soil? Step forward the migration-maven Barbara Roche, the intensely ethnocentric Jewish minister who opened Britain’s borders to the Third World during the New Labour government:

One of Roche’s legacies was hundreds more migrants camped in squalor in Sangatte, outside Calais, where they tried to smuggle themselves onto lorries. News about the new liberalism — and in particular the welfare benefits — now began attracting Somalis who’d previously settled in other EU countries. Although there was no historic or cultural link between Somalia and Britain, more than 200,000 came. Since most were untrained and would be dependent on welfare, the Home Office could have refused them entry. But they were granted ‘exceptional leave to remain’. (Conman Blair’s cynical conspiracy to deceive the British people and let in 2million migrants against the rules, The Daily Mail, 26th February 2016)

It’s no coincidence that Jared Diamond and Barbara Roche are both Jewish. Jews like Diamond supply the anti-White propaganda and Jews like Roche supply the anti-White practice. The great White writer Horace (65–8 BC), by contrast, supplied the truth. Two millennia ago he expressed the folly of importing savages into civilization with eight words of crystal-clear Latin: Caelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt — “They change their skies, not their souls, who rush across the sea.”

A humbly born White genius

Horace’s poetry is still something to marvel at, a miracle of White genius that has proved far more lasting than bronze. Aptly enough, the word “miracle” comes to us from Latin. It was originally miraculum, meaning “thing of wonder, marvel.” That’s why I called those police-photos of Black savages a miracle of migration. They were something to marvel at, a vibrant vision from the capital city of a nation that once imposed civilization on Blacks and would never have dreamed of importing Blacks to impose their savagery on us. Then Jews like Jared Diamond began to pump out anti-White propaganda and Jews like Emmanuel Celler (1888-1981) began to destroy pro-White immigration law. The results are plain to see across the West.

Humbly born Yorkshire genius John Harrison and one of his mechanical marvels (image from Wikipedia)

Humbly born Yorkshire genius John Harrison and one of his mechanical marvels (image from Wikipedia)

But there’s another kind of miracle in the story of Aled Jones and the machete-wielding savage who threatened to cut his head off. That savage was after the miraculum mechanicum, the mechanical marvel, that Jones was wearing on his wrist. There are many centuries of White ingenuity and effort behind even the cheapest watch, but how many of the rich White men who wear the most expensive watches stop to think about that? How many of them think about the humbly born Yorkshire genius John Harrison (1693–1776), who contributed more to watchmaking, technology, and navigation than all the Blacks who have ever lived? Alas, too many White men wear expensive watches only as a celebration of themselves and their success. They never stop to think what those watches represent. Or what the robbery of a watch by a Black represents. The marvellous watch represents civilization and the Black robber represents savagery. How many of the White victims of Black Rolex-rippers have recognized that? Very few, I’m afraid. And while rich Whites are happy to spend huge sums aggrandizing themselves with the shiniest products of White civilization, from Rolex watches to sports-cars to private jets, how much are they prepared to spend defending the civilization — and the race — that gave them those things?

Blacks and Muslims not needed

But the non-White savage that Aled Jones encountered in London was a threat to much more than the marvel that Jones carried on his wrist. He was also a threat to the marvels that Jones carried inside his head. Jones has great musical talent and a profound knowledge and appreciation of the glories of the Western classical tradition. He can read music and commune with the genius of White giants like Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. And his mother-tongue is Welsh, part of the true and organic diversity of the British Isles that is threatened by the artificial and imposed diversity of Third-World migration. We don’t need any Blacks or Muslims in Britain at all. They are a curse on us, not a blessing as the left so loudly and mendaciously proclaim.

All of that is obvious in the story of the Welsh musician and the non-White savage who threatened to cut his head off with a machete. It was one small encounter between civilization and savagery that symbolized a much bigger migration disaster. But the BBC and rest of the leftist media won’t tell you that. Even as they report clear proof of the evil insanity of Third-World migration, they go on supporting it and blaming all problems on White racism. They’re not sane or rational and they’re certainly not well-intentioned. That’s why we have to fight them, defeat them, and ensure that civilization survives.

What Is White Culture? Flushing anti-White genocidal rhetoric down the drain once and for all.

/24 Comments/in Featured Articles/by D. F. MulderIt is often said by the [many] haters of the White race that there is no White culture, whether those haters be avowed wokeshevik elites or modern conservative rubes unwittingly attempting to please them. Just as these doofuses aggressively spread the lie that race is just skin deep, they also strive to reduce Whiteness to absurdity, arguing that differences between European populations vary so much that there is no commonality between them. But is this really true? It is not, thankfully. It is but another lie peddled by the predatory Western/Globalist power class, another fiction imbuing and animating Cultural Marxist propaganda, all meant to unpeople our people.

So what are these common traits, this culture common to all European peoples? Let us begin, shall we?

1) It must start in antiquity of course. No analysis of the issue would be complete without reference to the Ancient Greeks and Romans, but especially the Greeks. It is in Greek philosophy and math that Western history truly begins. The Greek canon is unparalleled in its intellectual accomplishments. From drama (Homer, Sophocles) to mathematics (Euclid, Diophantus) to philosophy (Socrates, Plato, Aristotle), Ancient Greek contributions to the world’s knowledge base are at least as impressive or more so as any other people’s or period’s. Of course anyone can learn or learn to appreciate Ancient Greek genius, but it is really only White people who identify with it, who say, “That is my history. Those are my people.” There is a connectedness there that can not be taught or manufactured. It is a matter of identity and of cultural and genetic continuity. No amount of state or semi-state propaganda will ever make anyone named Mesut Ozil, Mohamed Saleh, or even Giannis Antetokounmpo identify with that history or that tradition. It is ours. It is not the glorious history or tradition of any other people, whether they be Turks, Arabs, or Nigerians. The same is true of various Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers from Descartes and Kant to Locke and Nietzsche, but it is especially true of the Ancient Greeks. There is, without a doubt, a certain continuity of thought in Europe stretching back over 2,000 years.

2) Second on the list is foods. There are certain foods common to all of Europe. These foods vary regionally, but there are foods that are distinctively or at least massively European. Whites dominate the production and sale of these foods. They have more or less always been widespread in Europe and we globalized them. Whites created/invented these foods themselves or borrowed them in early antiquity or prior and turned their production into an art form. They made them theirs, in other words.

The first food type on this list is cured meats: Pastrami, Prosciutto, Speck, Salami, Chorizo, Serrano, Bacon. Indeed, the European tradition of meat prepping and curing may be part of the reason Europeans have such a visceral reaction to the “eat the bugs” propaganda emanating from World Economic Forum types and other predatory capitalists and banksters. We are a meat-eating people. We are the masters of meat and of animal husbandry, and we have been ever since our people wandered off the Pontic-Caspian Steppe.

Second on this list must be dairy generally, but cheese especially. Remember, a love of milk is basically White supremacy, folks. The White love of dairy explains why lactose intolerance reaches its lowest levels in the Whitest of all places (Schleswig-Holstein). Indeed, this may be a major contributor to why Whites tend to grow bigger and stronger than other groups, and not just physically, but mentally. European cheese is unrivaled in its quality and flavor. Nobody makes cheeses like Whites make cheeses: Gouda, Havarti, Emmentaler, Gruyere, Cheddar, American, Stilton, Roquefort, Gorgonzola, Parmesan, Mozzarella, Manchego. Whites are the cheese masters.

There are just some foods Whites love and are masters at crafting. Cheese and cured meats have to be the top two on this list. And while other things could be placed on the list of distinct European culinary specialties (like bread for instance), I think beer belongs in the third spot. Beers are produced in nearly all regions of the world today largely on account of contact with Europeans and the movement of Europeans to new places and continents. East Asia and Latin America are premier examples of this. Nonetheless, no one makes beers like the White man makes beers. No one. Even here in America, Whites love their beer. They drink very crappy beer for the most part, since Americans are not really known for their sophistication in anything, but they love their beer. No matter who is brewing it and no matter where, aspiring brewers are copying the European masters when it comes to brewing beer. Sometimes they may be trying to emulate Guinness or Newcastle, but as a general principle, brewers the world over are trying to recreate something crisp, smooth, and balanced in its overall hoppiness, like the pilsners and helles beers of Central Europe, from southerly and easterly German or former German regions specifically. I have found that as a general rule, the longer a brewery has been in existence, which is to say perfecting its craft, the better the beer. Spaten is my brew of choice (1396), though I can swing a Weihenstephaner (original helles) from time to time. The latter has been brewing its beer for just under 1,000 years. There are some quality kolsches about too, to be fair.

3) There is a certain aesthetic outlook that is more or less unique to White, Western civilization. It is one that emphasizes two things primarily: discipline and fertility. Those are the traits that define classical European art, from the Renaissance and before: beautiful, proportionate men, and beautiful, fertile women (see Rubens or Botticelli). These things are prized in White societies. Indeed, fertility is prized in almost all traditional cultures, whether Christian or pre-Christian. It is only our degenerate modern culture which treats reproduction and motherhood/fatherhood as an onerous burden rather than a wonderful, even liberating gift. Again, this may not be unique to Europa, but it is a central part of our culture. That is why even today body sculpting/building is so popular on the political right and even in the smallest, Whitest towns in the far interior. You will uncover these aesthetic values in most any work of art from the Renaissance period. This aesthetic specifically values our looks and our beauty. You are not going to get Bantus and Indonesians to deeply appreciate values that aren’t theirs or images of beauties that aren’t common to their ethnies. Moreover, wherever you see Whites promoting fatness or fat inclusion or denigrating motherhood and celebrating careerism, you should know you are listening to someone who has been deracinated from their roots, from their culture. The farther we wander from a love of self-control and self-discipline and the veneration of fecundity and fruitfulness, the farther do we stray from the European tradition.

The same goes for classical music. Does it not seem to you that it is only our ear that appreciates it? You will never get large segments of most other populations to identify with or appreciate classical music. That is why classical orchestras are still dominated by White people, a fact which has of late become but another cause for non-White/anti-White griping, consternation, and calls for more equal representation. They don’t like our music and they don’t identify with it. You can’t make aspiring rappers into cellists, no matter how much propaganda you peddle. Classical music is a White thing and it always will be. Anyone can play it to be sure, but not everyone will. Our artistic geniuses are ours. Bruegel and Vermeer are, most of all, appreciated by our eye, as Beethoven and Chopin are, most of all, appreciated by our ear—because they are part and parcel of our White culture, and no one else’s. They speak to our nature and our spirit, no one else’s. Should we even let non-Whites play this music? Should we tolerate this? Is this not cultural appropriation? Western music and Western painting are White culture, full stop.

There is even a uniquely White architectural tradition. It may be diverse and variegated, but there is a continuity there. The fact that the architecture in our nation’s capital (I am talking of course of the Capitol Building and the White House and the other major architectural structures/buildings) draws so heavily on ancient architectural concepts (think of all the Ionic columns in D.C.) proves that there is continuity—ethnic, moral, spiritual, cultural—between Ancient Greece and America. Our people are not all the same, but there is a commonality and continuity there. Well, dipshit, that is White culture. That is it, and it is very real. So, the next time someone asks, “what is White culture?”, or declares that “there is no White culture!”, point them to this article. Because there clearly is a White culture and we are immersed in it, though many White westerners seem disturbingly unaware of that fact.

4) A fourth distinctive trait of White culture is a deep respect for objective truth. What has driven unrivaled White accomplishment and contribution in so many scientific and intellectual fields is an abiding respect for truth, and the noble, relentless pursuit of the universe’s mysteries. Cultural Marxist Western leaders wish to weaken the ties between our minds and reality, because it renders ordinary people easier to tyrannize. When you can’t discern between blatant falsehoods and obvious truths, you can’t effectively resist. Belief is necessary for action, particularly impassioned action. If you will believe boys can be girls, you will believe literally anything at that point. Nothing is worth fighting for, let alone dying for, if nothing matters, if nothing is true. Anyone who would assent to the most obvious of lies is three quarters slave already. He has already lost any sense of self-respect and probity. He will go along with most anything at that point. Of course, our vile overlords still think some things do matter and are true. Racism is the most evil thing that ever happened to the world. This is self-evident of course. White racism that is. We are told this every day, and we must repeat it as a kind of mantra, as an implied oath to the great and glorious Cultural Marxist state. Our overlords are very selective about these things. Morality is relative, but their moral values are objectively and indisputably and absolutely correct, and they enforce them with the vigor of crazed Jihadists. One wonders how we have allowed ourselves to be vassalized by such shallow nitwits.

5) Fifth on the list has to be an enduring respect for freedom of speech and expression. Westerners have understood since the Enlightenment is that there is no genuine science or the possibility of an informed public without free speech, and no real democracy without it either. Tied to an enduring belief in free speech and expression and a willingness to use state violence to protect that right, is a healthy respect for self-actualization and individuation. This respect can of course devolve into a shallow degeneracy, a gaudiness as it were, including excessively revealing clothing and the like. There has always been a balance in Europe between the traditional value of modesty, and respect for and tolerance of individual expression. However, this respect for the right of people to say what they want and wear what they want is distinctively European. It is deeply rooted in the Enlightenment. It extends even to body art and sexuality. Other peoples are by and large far more inclined to crush individual self-expression of all sorts. This is because the natural impulse to use authoritarian tools and tactics to crush individual uniqueness is not as well tempered by the European respect for the individual. In less stable, more dysfunctional, more mistrusting societies, nonconformity is viewed as a threat to tradition, to the government, to the often comfortable social order. It is therefore more feared than honored.

To make matters worse, criminal governments, such as ours, are keen to exploit the divides and anxieties of mistrusting and disordered societies, so as to enlarge themselves and their powers, and secure their positions thereby. Diversity is therefore the gift that keeps on giving for our tyrannical governments and their tyrannical police state apparatuses. Our governments are deliberately sowing low-level chaos amongst the people so as to gain from it. Terror act? The government needs more powers. Organized retail theft? The government needs to put more of its soldiers on the streets. They import our replacements and all the poverty and problems our replacements carry with them, and they use natural or even engineered fears about social instability and crime and the like, as a never-ending excuse to crack down on us, on any White person who dares to complain about being replaced, displaced, and/or dispossessed. There are too many orthodoxies to count now. “Cancel culture” and “hate” laws are but symptoms of these lamentable trends. We are not becoming freer in the West, but in fact we are far less free in recent decades.

6) Also emanating from these speech and expression rights are the defense of oneself, one’s property, and other essential rights. As you see these rights falling by the wayside in Europe and America, these regions are becoming effectively less White and less European. We are losing our culture to more primitive cultures. The American police state’s drive to punish wrongthinkers/racists is overwhelming our longstanding legal tradition of permitting men to defend themselves from wrongdoers and transgressors, among other rights and traditions. Much of the law today is being sullied and subverted by alien peoples and very bad ideas, from critical race theory to disparate impact to no-knock warrants to mass surveillance to the plea bargain system, the grand engine of American tyranny. Equality under the law, consent of the governed, and due process are largely alien concepts to other peoples. Even today, most non-White populations do not uphold these principles to any meaningful degree in their own nations. Even when they are trying to, openly and committedly at that. They know about them, they may even wish to emulate them, but they cannot realize them. White Westerners took them for granted throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries. And that is why we are losing our societies as our values wither away. We didn’t realize how valuable these things were. So we lost them. We did this in two ways primarily. In the first place, we created a massive police/security state that gobbled them all up. We were brainwashed by the government into believing that this was how we uphold these principles. The way you make yourself strong and free is by enlarging the government and enabling it to amass massive armies of government soldiers, which get to walk the streets and harass you about most anything. Pretty transparent trickery of course, but with the aid of the news media, they pulled it off. In fact, a massive police presence does not uphold rights, it obliterates them. The CIA and FBI and law enforcement officers from the national all the way down to the local, couldn’t care less about equality before the law or the consent of the governed. They don’t care about your rights. They care about power and the preservation of power [in their own hands]. They care about keeping their jobs as well, and following commands from above. Your rights are really not high on the list, if they are on the list at all. This is as true in America today as it was in the Soviet Union under the terroristic reign of the secret police.

The other way we did so was by believing obvious race egalitarian lies. Westerners were propagandized into thinking that any people could sustain their ideals. But they can’t. Because we replaced ourselves by subscribing that everyone is an interchangeable economic unit, we are surely losing our culture and even a secure biological existence . We placed the valuing of diversity and the worship of markets over the bedrock principles of our civilization. The spirit and genes of our people are the bedrock of our civilization. As they go, it all goes. And it has. When Whites abandoned their sense of race pride, without knowing it they were basically throwing their civilization in the trash heap of history. No one can sustain Western civilization but us. If we do not retain a dominant position in our societies, we cannot preserve our civilization.

7) A healthy respect for markets, and by extension, property rights, are fundamentally White, western values. But there is a big difference between a healthy respect for a thing and a blind faith in it. It is really only in America where this healthy respect has become very unhealthy. Capital markets are like meat. It is quite healthy to eat meat, red meat even. On the other hand, it is quite unhealthy to eat cheeseburgers every day for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. A diet, like a society, needs more than just free markets. Fundamentalist capitalism is a cancer eating away at everything in the country, from democracy to living wages to the safety net to the border itself. It turns out, you don’t need completely free markets to enjoy the many benefits of markets. A multitude of European nations prove this definitively. But the excesses of markets can be very destructive to society at large. Just look at how 18–30 year-old women are selling their bodies all over the internet today. When only the dollar is sacred, nothing is sacred, everything is for sale. Even democracy itself. And of course there have been European nations that have adopted communist economic systems and the like, at least temporarily, but for the most part these foolish experiments have been all but abandoned. However, every year it seems there is a new crisis that Republicans/Conservatives refuse to even try to address in the name of fiscal austerity and responsibility, and letting markets sort it out. And every year the problems get worse! Of course there is always plenty of money for the weapons manufacturers and the refugees and fancy new FBI/KGB buildings/headquarters, just not for the problems actually afflicting ordinary Americans.

The White race is a race of industry and action. If there are trees about, we may well cut them down and build homes—although we also have pioneered conservation and the national park movement. If there is some resource under the ground, we find a way to get it to the surface and use it. These are good things. But we should not confuse this healthy impulse with the false, largely superstitious belief that markets are always perfectly rational or efficient. They are not. Yes, some people who get very wealthy are very skilled and intelligent. But many are neither skilled nor intelligent. Take the Kardashians for instance. A healthy respect for markets is a good thing, but the free market is not god and should not be treated as a god. We should never let a foolish belief in the wonders of markets get in the way of feeding the poor or making sure people are housed. Most all White populations know and understand this. All should. No majority White state should resemble the Congo, as some American states are starting to do.

8) The religion of Christianity and all of its intellectual offshoots are inseparable from White culture. Almost all Medieval, Renaissance and Enlightenment thinkers rooted their thinking in Christian ideas. Even the philosophy of natural law, is grounded in Christian thought. White lands were once more or less coextensive with Christendom itself. Remnants of folk religions—religions arguably healthier, more organic, and more truly native and natural for White peoples than modern Christianity—persist in various forms in White culture, but the effects of Christianity are far larger and far more recent. Christian values and thoughts are the fruit of White culture. They may not end at Whiteness exactly, as Christianity has really devolved into a global, universalizing religion, to the detriment of the race that founded it and developed it. But these values and mores are inseparable from Whiteness. Whiteness can be distanced from Christianity substantially, but it can never be entirely separated from it, just as Whiteness cannot be separated entirely from the Ancient Greek canon. Christianity can be distanced from Whiteness, as it is often is today, in awful and destructive ways, but it cannot be removed from Whiteness entirely. The form Christianity took historically, its ideals, its spirit, this all is inseparable from the genetic and cultural substratum of the European continent and diaspora. Indeed, there is a difficult chicken-and-egg problem here: What role does the unique European genetic constitution have in predisposing Europeans to the cultural values of Christianity in times past and present?

9) No list would be complete without including these: Heroism, self-sacrifice, war, & conquest. Unfortunately, the military technologies our own people created through a combination of genius and will, are now being turned inward on our own populations, and used to subdue and enserf the people themselves. Still, there is no discussion of Whiteness and White history without a discussion of our unrivaled military successes. The White race is the champion of warfare and weaponry. Killing and conquering are certainly part of that systematization. Our people killed and conquered everything and everyone, before giving it all up in the name of “human rights” or “loving diversity” or some such hogwash. I guess when you reach the top there is nowhere to go but down, eh? Still, that curiosity, that life drive, that love of expedition and conquest, has been applied to so many domains, even space. Exploring new domains, no matter how challenging, no matter how far one has to reach, is White culture. Grabbing the lowest hanging banana is the culture of other peoples. The ability and desire to do great and heroic things, which the entire species esteems and benefits from, is inseparable from the White western spirit and from the culture which springs from that spirit.

10) Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, “White culture” is anything non-Whites and anti-Whites and Western power structures generally struggle to define precisely, but detest as either “vestiges” of or “pillars” of White supremacy. If Western governments loathe it and are trying to replace or dismantle it, from traditional sex roles to knowledge of firearms, chances are it is some part, lesser or greater, of White culture. Resist it, because they hate you and are trying to destroy you. They can dress their genocidal intentions up in the language of social justice or whatever else, but the truth is they are just trying to eliminate you, your race, and your culture And they are succeeding.

Liberating Lady Liberty A closer look at Emma Lazarus and her “New Colossus”

/7 Comments/in Featured Articles/by American KroganEditor’s note: Almost a year ago I posted a video by American Krogan titled “On Emma Lazarus.” He now has a Substack (please subscribe) under the name Wilhem Ivorsson and he has made the video into a written version, complete with citations. Enjoy.

In reality, the lines are from a sonnet called The New Colossus, written in 1883 by Emma Lazarus, a Jewish writer and social activist. Unbeknownst to most Americans, the poem had no official association with the statue until 1903, when Georgina Schuyler, one of Emma’s friends, led a civic campaign to have the sonnet cast onto a bronze plaque and mounted inside the lower level of the pedestal, 17 years after the statue was first dedicated. The poem was rarely mentioned in the mainstream press until several decades later.

Emma Lazarus

The New Colossus appears to have gained traction once Slovenian author and socialist immigrant Louis Adamic began quoting it in his writings during the late 1930’s to combat the Johnson-Reed act of 1924, which set restrictive immigration quotas in order to maintain America’s ethnic homogeneity. Adamic was an avid Marxist who advocated for ethnic diversity in the US, and coincidentally, his publisher, Maxim Lieber, was named by the Soviet spy Whittaker Chambers as an accomplice in 1949. Lieber fled to Mexico in 1951 and eventually back to Poland. Louis Adamic committed suicide in 1951 under suspicious circumstances.

Over time, the poem’s association with the statue has grown to the point of absurdity. Again, today, questioning, altering or rejecting the poem and its meaning is a kind of political blasphemy. For example, back in 2019, the press berated the Trump Administration for supposedly “rewriting” Emma Lazarus’s words when Ken Cuccinelli, Trump’s head of Citizenship and Immigration Services, tried to reorient the poem’s meaning.

CBS wrote: Trump’s top immigration official reworks the words on the Statue of Liberty. PBS wrote: Trump official says Statue of Liberty poem is about Europeans. The New York Times wrote: What the Trump Administration Gets Wrong About the Statue of Liberty. Vox wrote: Trump official suggests famous Statue of Liberty sonnet is too nice to immigrants. The Jewish Forward wrote: Ken Cuccinelli Isn’t The First Trump Official To Go After Emma Lazarus.

All these accusations of “rewriting” Emma’s poem were ironic, since essentially it was Emma’s poem that was used to rewrite America’s identity and its stance on immigration. Concerning the period of the Johnson Reed Act of 1924, leading up to the Hart Celler act of 1965, Hugh Davis Graham wrote in his book Collision Course:

Most important for the content of immigration reform, the driving force at the core of the movement, reaching back to the 1920s, were Jewish organizations long active in opposing racial and ethnic quotas. These included the American Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Committee, the Anti-Defamation League of B’nai B’rith, and the American Federation of Jews from Eastern Europe. [1]

Curiously, in 1883, when a fundraising committee asked Emma Lazarus to donate an original work to an auction intended to help pay for the pedestal’s construction, Emma declined saying that she would not write about a statue. She only changed her mind after Constance Cary Harrison convinced her that it would be of great significance to immigrants sailing into the harbor. [2]

As Harrison later recalled, her ploy to win over the young writer involved highlighting the plight of immigrants from a very specific ethnic background:

Think of that Goddess standing on her pedestal down yonder in the bay, and holding her torch out to those Russian refugees of yours you are so fond of visiting at Ward’s Island. [3]

These “Russians” were in fact Emma’s fellow Jews fleeing pogroms in Russia after Czar Alexander II’s assassination in which Jewish radicals had been implicated. In any event, It seems that just as the Anglo-Saxon founders of America had a preference for immigrants of a certain ethnic background, Emma had her own preferences too. She didn’t write poems about Irish or Italian gentiles who were immigrating in large numbers at the time. Nor did she write about emancipated slaves in the South or Chinese railroad workers out west. To the extent that she wrote about any people, it was almost exclusively Jews.

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi

The greatest tragedy in the history of Lady Liberty is that more people know who Emma Lazarus was than the Frenchman who designed it; Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi. The statue was a gift from France to celebrate the nations’ friendship and alliance. It was modeled after Libertas, a roman goddess who was often associated with freed slaves in antiquity. But the monument really had nothing to do with the emancipation of African slaves in the US, and great care was taken in the design to avoid such associations. [4]

A Roman coin with Libertas. Circa 125 BC.

The meaning behind Lady Liberty is no where near as convoluted as popular media makes it out to be. The Roman goddess, Libertas, has been used in various forms by many European peoples for centuries. There’s a version of her on top of the Capitol building that was put in there in 1863. France used her on their seal for the second French Republic in 1848. There’s also the Dutch Maiden, the United Kingdom’s Britannia, and the Italia Turrita.

In the American setting, the figure of Libertas was used as a symbolic reference to the freedom the British colonists had gained from their English monarch, King George. The date written on the statue’s Tabula Ansata is July 4th, 1776, the date of independence from England. This is also the date mentioned numerously in French fundraising pamphlets which, as far as I am aware, never spoke of emancipated slaves or immigrants.

It is true that Édouard Laboulaye, one of the key impetuses behind the statue, was a passionate abolitionist who advocated on behalf of emancipated slaves, but his motivation for building the monument was to further solidify the historic Franco-American alliance.

In 1875, he launched a subscription campaign for France’s half of the funding saying:

This is about erecting in memory, on the glorious anniversary of the United States, an exceptional monument. In the middle of New York’s harbor, on an islet that belongs to the Union, and opposite Long Island, where the first blood for independence was spilt, here will stand a colossal statue, framed on the horizon by the great American cities of New York, Jersey City and Brooklyn. On the threshold of this vast continent full of a new life, where all the ships of the world arrive, it will emerge from the heart of the waves, it will represent: Liberty enlightening the world. At night, a luminous halo emanating from her forehead, will radiate in the distance on the immense sea. [5]

The idea of Liberty enlightening the world was that others could achieve what America had by following in its example as a republic. Laboulaye and others didn’t see Lady Liberty as a call for endless, unqualified immigration, and it was not a statement that anyone could be American regardless of national origin.

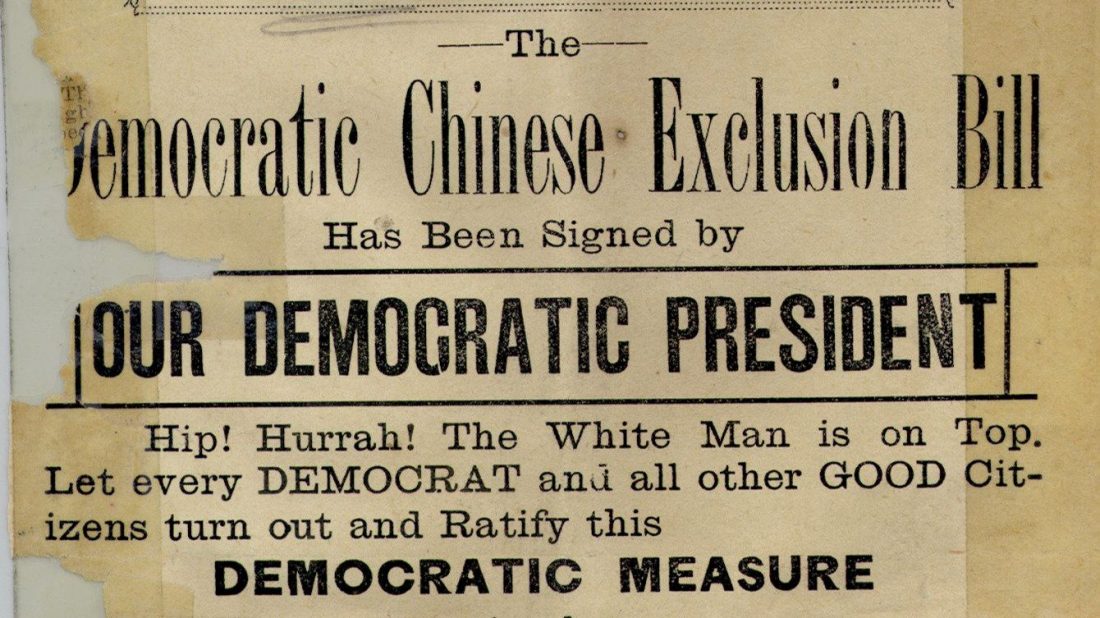

To drive home the absurdity of claims to the contrary, four years prior to the the statue’s dedication, America had passed the Chinese Exclusion act thereby barring an entire racial bloc from immigrating.

Shortly before being assassinated in 1865, Lincoln, the great emancipator, had told General Benjamin Butler:

“I can hardly believe that the South and North can live in peace, unless we can get rid of the negroes…I believe that it would be better to export them all to some fertile country…” [6]

In the 1880s, race riots were common. Most Americans continued to share Lincoln’s sentiments and saw ex-slaves as an unresolved problem with many politicians and private citizens continuing to argue for them to be repatriated to Africa.

The Cleveland Gazette, an African American newspaper wrote the following regarding the Statue of Liberty’s dedication:

“Liberty enlightening the world,” indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders. [7]

Such language is often highlighted to assert that America was failing to live up to its supposed ideals, but the reality is that America’s first naturalization act in 1790, in no uncertain terms dictated that citizenship was reserved for “free white person[s]…of good character.” When Thomas Jefferson said in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” he was speaking in a political sense to King George, a monarch, and not a literal sense to mankind as a whole.

Other contemporary state documents remove the ambiguity for the modern reader, such as that of Virginia’s Declaration of Rights in 1776:

“…all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights…”

None of the sentiments outlined in any of our founding documents sought to convey that all men, regardless of racial background or national origin, were equal and interchangeable in a literal sense commensurate with modern notions of “diversity, equity and inclusion.”

Thomas Jefferson, despite being a slave owner himself, did support emancipation, but he qualified this in his Notes on the State of Virginia:

“Among the Romans emancipation required but one effort. The slave, when made free, might mix with, without staining the blood of his master. But with us a second is necessary, unknown to history. When freed, he is to be removed beyond the reach of mixture.” [8]

Of note here is that the definition of “Civil Rights” has changed substantially over time. In 1866 when the first Civil Rights Act was passed, John Wilson, a member of the Radical Republicans, described what the legislation was intended to encompass when he presented it before congress:

It provides for the equality of citizens of the United States in the enjoyment of “civil rights and immunities.” What do these terms mean? Do they mean that in all things civil, social, political, all citizens, without distinction of race or color, shall be equal? By no means can they be so construed. Do they mean that all citizens shall vote in the several States? No; for suffrage is a political right which has been left under the control of the several States, subject to the action of Congress only when it becomes necessary to enforce the guarantee of a republican form of government (protection against a monarchy). Nor do they mean that all citizens shall sit on the juries, or that their children shall attend the same schools. [9]

Let’s return to Emma Lazarus’s poem, The New Colossus. It’s quite short so let’s read it:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

In her biography of Emma Lazarus, a fellow Jewess, Esther Schor, considers the meaning that can be gleaned from these lines:

Perhaps, too, these words issue a mild command that a new-world statue must embody a new ideal. But before her vision takes shape, she pauses to smash an idol of the Old World: Helios, the sun god, a figure of imperial conquest, “astride from land to land.” Given that Bartholdi’s statue was intended to ennoble enlightenment, her reference to Helios’s lust for domination is indecorous, to say the least.

In “Progress and Poverty,” she had already impugned the lit lamp of Science for being complicit with exploitation. Now, renaming Liberty Enlightening the World “Mother of Exiles,” she relieves this giant female form of a heavy inheritance of tyranny. At the same time, she places a new burden upon her, asking that she nurture and protect conquest’s victims.

The “imprisoned lightning” of her flame, an emblem of captive, not liberating light, insists that true enlightenment must wait on freedom. Until then, all light glows against a scrim of darkness, the same darkness in which the ignorant slaves of “Progress and Poverty” toiled. [10]

Esther Schor seemingly acknowledges that Emma profaned Bartholdi’s original intent and yet embraces Emma’s view as the more legitimate one anyway. She continues:

Defying the “storied pomp” of antiquity, precedent, and ceremony, the statue speaks not in the new language of reason and light but in the divine language of lovingkindness. To worldly power, she sounds a dire tattoo: “Keep, ancient lands”; “Give me your tired.” To the abject, she offers the silent salute of her lamp. What it illuminates are shapes of human suffering, the “huddled masses,” the wretched refusés on the Old World’s “teeming shore.” Emma Lazarus had finally arrived, from a glimpse of the “undistinguished multitudes” in her elegy to Garfield, at a more radical, embracing vision of American society, and she had been led there by her Jewish commitment to repair a broken world. She knew well that for these homeless throngs, becoming individuals—becoming free Americans—would not be easy. But it was their destiny. In time, the Mother of Exiles assures them, that is what they would grow to become. [11]

Putting aside that the base inspiration of the Statue of Liberty was the Roman goddess Libertas and that Helios wasn’t really associated with conquest, the Colossus of Rhodes, was literally built using the siege equipment left by the Macedonians after their failed attempt to take the city, and, like its modern female counterpart, was a monument to continued independence.

Now, one could make the case that Esther Schor, is anachronistically imbuing Emma with 21st-century interpretations of tikkun olam, but it seems fairly obvious that Emma was driven, at least in part, by a kind of Jewish ethnocentrism, and a resentment of Western society and her place in it as a Jew.

Again, Emma didn’t write about the plight of blacks in the South, nor did she spend her time protesting the Chinese Exclusion act. Before the term Zionism had even been coined, Emma was traveling around Europe advocating for a Jewish ethnostate in Palestine. Her line “keep ancient lands your storied pomp” in defiance of European antiquity, precedent and ceremony is ironic since a great deal of her other literary works focused on exalting Jewish antiquity, precedent and ceremony. In fact, Emma is considered by many to be the archetypical American Zionist. Oddly enough, Esther Schor admits as much in the preface of her book:

These days, Lazarus’s dictum that “Until we are all free, we are none of us free” is widely taken to be a universalist credo; similar statements are attributed to Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. In fact, Lazarus addressed this comment expressly to the privileged, emancipated Jews of the West, taking them to task for “not [being] ‘tribal’ enough”—that is, for failing to recognize the persecuted Jews of Russia as their brothers and sisters. [12]

But in the same preface, she asserts that Emma’s behavior was more or less a proto-universalist movement gearing up to include all of humanity.

For Emma Lazarus, being Jewish meant acknowledging one’s bonds to people distant in both place and time. Being a free Jew, in a world where Jews were being persecuted and expelled by the thousands, sometimes even killed and raped, was to incur the obligation to bring freedom to others. It was Lazarus’s genius to understand that the obligations of freedom pertained not only to Jewish Americans, but to all Americans. [13]

Needless to say, I find this highly disingenuous and self-serving. If we look deeper into Emma’s family history, such notions of her being some proto-archetypal form of modern “diversity, equity, and inclusion” becomes somewhat absurd. Her family was among the original twenty-three Portuguese Jews who moved to New York in 1654 when it was still called New Amsterdam and was controlled by the Dutch. [14]

They were fleeing the return of the Inquisition in their settlement of Recife, Brazil. So yes, her family was fleeing persecution, but Recife, Brazil was one of the most important colonies in the New World in terms of establishing the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the infamous Middle Passage.

According to Jewish author Herbert Bloom:

The Christian inhabitants of Brazil were envious because the Jews owned some of the best plantations in the river valley of Pernambuco and were among the leading slave-holders and slave traders in the colony. [15]

In reference to slave colonies in Brazil and the West Indies, Jewish historian Marc Lee Raphael wrote that:

Jews also took an active part in the Dutch colonial slave trade; indeed, the bylaws of the Recife and Mauricia congregations (1648) included an imposta (Jewish tax) of five soldos for each Negro slave a Brazilian Jew purchased from the West Indies Company. Slave auctions were postponed if they fell on a Jewish holiday. In Curacao in the seventeenth century, as well as in the British colonies of Barbados and Jamaica in the eighteenth century, Jewish merchants played a major role in the slave trade. In fact, in all the American colonies, whether French, British, or Dutch, Jewish merchants frequently dominated. [16]