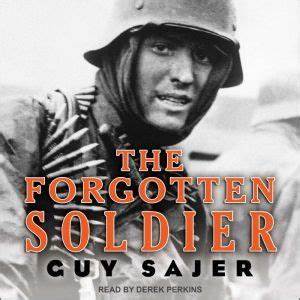

Review of “The Forgotten Soldier” by Guy Sajer, Part 3 of 3

Part Four (Winter 1943 — Summer 1944)

Following Sajer’s evacuation to the west bank of the Dnieper River, the anticipated German camp where they will be refitted and allowed to rest and recover proves to be an illusion. The chaos that reigned along the east bank is mitigated on the west bank but not eliminated. For men used to German exactitude within the Wehrmacht, the disorder was disconcerting. They are left in the open and then interrogated by military police who seem to view them as cowards if not outright traitors for their retreat. It is a jarring sequence; we know the hell that Sajer and the other survivors endured just to make it to the west bank — their courage and almost-superhuman will to live was beyond doubt. Yet, the retreating men were treated with derision. And the hope that the mighty Dnieper River would stall the Soviet onslaught also proved to be illusory — desperate fighting takes place along the entire front with Kiev being the Soviet focal point. It is at this point that the sheer advantage of Soviet matériel became overwhelming and they appeared to gain almost complete air superiority — to say nothing of the seemingly inexhaustible supply of Soviet soldiers.

From the Dnieper, the new German front largely broke, although not without fierce fighting. The Germans were hurled back again in a chaotic and sanguinary retreat through Ukraine. Sajer was, at this point, very sick — and indeed he was sick for seemingly much of the latter half of the book. He developed dysentery and recounted how, in what must have been excruciating, he soiled himself on a moving truck while in acute abdominal pain. He was mortified by the time he finally made it to something like a field hospital — filthy and disgusting in every sense of the term. He was promised leave to rehabilitate but it was cancelled as the situation continued to deteriorate. He is forced to man the line while his illness was still raging. He did this several times. When he and his fellow soldiers were reunited with Hauptmann Wesreidau a few weeks later, Wesreidau asked him if he recovered during his leave to which he responded that he never was able to take it. Wesreidau, as a father figure to Sajer, expressed that enormous sacrifices were expected from all of them. To Sajer’s surprise, his Großdeutschland regiment was fully equipped and supplied with the best of what the Wehrmacht had left and was used as a mobile force sent to weak points in the German lines. While the entire German front continued to collapse, the regiment was moved from one emergency to the next. But at least during this brief period, Sajer tasted victory over the Soviets as opposed to continual retreat. The mobile unit harried the Soviets in offensive action in an otherwise defensive German posture, which was followed inevitably by another retreat. Later, the irony of his “mobile” unit was that it would still be called a “mobile” unit long after it was reduced, either from want of fuel or machines, to being solely on foot.

Throughout the book, and it doesn’t matter when, Sajer describes combat in excruciating detail. The horror and fear are palpable in virtually every combat setting. One description of engagement suffices to convey Sajer’s ability to communicate what he experienced with the caveat that there are many more just like it:

What happened next? I retain nothing from those terrible minutes except indistinct memories which flash into my mind with sudden brutality, like apparitions, among bursts and scenes and visions that are scarcely imaginable. It is difficult even to try to remember moments during which nothing is considered, foreseen, or understood, when there is nothing under a steel helmet but an astonishingly empty head and a pair of eyes which translate nothing more than would the eyes of an animal facing mortal danger. There is nothing but the rhythm of explosions, more or less distant, more or less violent, and the cries of madmen, to be classified later, according to the outcome of the battle, as the cries of heroes or of murderers. And there are the cries of the wounded, of the agonizingly dying, shrieking as they stare at a part of their body reduced to pulp, the cries of men touched by the shock of battle before everybody else, who run in any and every direction, howling like banshees. There are the tragic, unbelievable visions, which carry from one moment of nausea to another: guts splattered across the rubble and sprayed from one dying man to another; tightly riveted machines ripped like the belly of a cow which has just been sliced open, flaming and groaning; trees broken into tiny fragments; gaping windows pouring out torrents of billowing dust, dispersing into oblivion all that remains of a comfortable parlor.

In the long retreat through Ukraine, Sajer introduced a new enemy in the guise of newly emboldened “partisans” whom Sajer and the other soldiers despised. Despite the relative successes of Sajer’s unit, the German lines continued to deteriorate across the southern front. There is then a book within a book in which Sajer detailed a war against the partisans during the German withdrawal, which added a new layer of anxiety and trauma for the soldiers. He notes how the same Ukrainian villages that welcomed the Germans as liberators from the Soviet yoke were now crawling with partisans and the unexpected violence that they brought to bear on the retreating Germans. The partisans also exacted a toll on the native population who were suspected of aiding the Germans and made otherwise friendly people wary and unhelpful. It was during this long retreat through Ukraine that Sajer witnessed the death of Hauptmann Wesreidau, who was killed when his car leading the caravan was destroyed by a partisan mine. The death of Wesreidau was a seminal moment for Sajer and the book — the war may have been lost by any measure at that point, but the death of Wesreidau seems to mark the defeat for his men. Collectively, they could not process his death even though they had seen, as a group, thousands of bloodied and disemboweled corpses strewn across the Russian Steppe. At least with Wesreidau, they had a commander who would shepherd them through the worst of what was to come; without him, they were like children without a father.

The partisan aggression grew fiercer as they were supplied by the Soviets with more and more sophisticated weaponry and tactics. Sajer notes another partisan engagement in which he was personally involved with the firefight that left virtually all of the partisans dead — partisans who had derailed a train going back to the front and killed more than a hundred weary German soldiers. Commanded by a group of the S.S., Sajer and other soldiers successfully attacked the partisan stronghold, and in the melee that ensued, Sajer killed his first partisan at very close quarters. A few of the partisans are captured and executed. The S.S. commander justified his actions because the “laws of war condemned them to death automatically, without trial.” Writing twenty years after the war, Sajer drips with anger towards the partisans. He viewed them as something like snakes who violated the rules of war that even the Soviets understood. He also agreed ultimately with the harsh justice meted out to partisans, noting without objection that, “partisans were not eligible for the consideration due to a man in uniform. The laws of war condemned them to death automatically, without trial.”

Part Five (Autumn, 1944 — Spring, 1945)

The German army was pushed from Ukraine. For Sajer and his compatriots, the escape was through Romania into Poland. Like similar retreats, this one was completely disorganized and marked by hunger and desperation. The men traveled back in packs and found a disabled German truck filled with provisions — they glutted themselves after weeks of starvation but only to have two of their group arrested by the military police on the route back and subsequently hanged as thieves. Sajer’s group was eventually organized with other retreating elements and a march back to Poland commenced. Once in Poland, and notwithstanding seemingly complete Soviet air superiority, the men were reorganized again. A theme that runs throughout the book: each successive retreat, which was costly in terms of men and matériel, forced the reorganization of the remaining forces into either a reconstituted version of their earlier units or scratch units altogether. Sajer, Lensen, Hals, and others were greeted again by the rigors of military discipline, which after their ordeal during the last several months was unwelcome. They were placed under the command of Hauptmann Wollers and sent to Lodz where they were resupplied. Sajer notes that many replacements were old men or virtual children; he wondered how these troops would be useful in combat. The Veteran rejoined the group where the division was regrouped and recounted recuperation in Germany; observing that German cities had been bombed into rubble. His ear was also missing. The Veteran explained to the group that this was total war.

The reorganized unit moved to relieve the German soldiers fighting on the northern front and they traversed on foot a new nightmare of endless miles without water or any available provisions. Some have complained that Sajer exaggerated the lack of food during the war but his refrain regarding hunger took center stage very late in the war. Considering that the Wehrmacht had a short supply of trucks, fuel, railcars, and men over a collapsing front the length of Russia, it does not strike me as surprising that the remaining troops would have been lacking food — even for days and weeks. Days of grinding hunger and fatigue blended with the endless and flat terrain in what can only be described as something otherworldly and wretched. It is at this point we wonder, perhaps more globally, what prompted Sajer and his fellow soldiers to survive under these impossible conditions — without food or support — and maintain their fighting prowess. Sajer writes:

Faced with the Russian hurricane, we ran whenever we could. … We no longer fought for Hitler, or for National Socialism, or for the Third Reich — or even for our fiancées or mothers or families trapped in bomb-ravaged towns. We fought from simple fear, which was our motivating power. The idea of death, even when we accepted it, made us howl with powerless rage.

On their way to the new front, they met with a completely disorganized group of German soldiers in flight. When Wollers attempted to reorganize them, he was greeted with derision as if the last marks of order within the Wehrmacht had broken down. If there is one passage that marks the end of the war, and there are probably many, it was this sorry scene. These retreating troops were more like starved and crazed refugees than a professional army. They insist that they are the men that were to be relieved and all that waits for Wollers and his relief force at the front is death. The entire sweep of the German soldier’s distress is put into stark relief here — the extreme cold, hunger, fatigue, and filth of the battlefield that existed alongside the disorder and lack of supplies. Their lives had become unbearable. He recalled that in late 1944 that “food was our most difficult problem. For a long time now we had received no supplies. … We became hunters and trappers and nest robbers.” As to the starving troops they encountered in flight, he noted that extreme hunger produced “a curious frame of mind. It is impossible to imagine dying of hunger. Our stomachs digested substances which would kill a comfortable bourgeoisie … in a few weeks.” He said that the situation got so bad that “men… no longer distinguished between enemies and friends … [and] were ready to commit murder for less than a quarter of a meal. … These martyrs to hunger massacred two villages to carry off their supplies of food.”

The group collectively retreated towards East Prussia, which was considered as much Germany then as Berlin or Munich are today. They were reorganized yet again for the defense, but this time of German soil. Lensen, who was the most strident patriot of the group, was East Prussian and excoriated his fellows for their defeatism in light of the pending invasion of Germany by the Soviets. Lensen was by far the most complicated of Sajer’s comrades in the Wehrmacht. Despite Sajer’s loyalty to France and his limited knowledge of the German language, many of his closest comrades still accepted him as a fellow German soldier, but there were a few instances in which Sajer faced abuse for his mixed ancestry. Much earlier in the book, in one of the more significant encounters between Lensen and Sajer, while they were drinking during a lull in the fighting, Lensen began criticizing France after Sajer had sung a French song, and Lensen’s drunken harangue made Sajer question himself and his toughness. He wrote then that “[he] found the war almost totally paralyzing — probably because of my soft French blood.” Sajer concluded that his poor soldiery was the result of his ethnicity and upbringing. However, despite the occasional abuse attributed to his French origins, Sajer felt particular pride at being a soldier in the Wehrmacht, especially after his service in the Großdeutschland in which he promised to “serve Germany and the Fuhrer until victory or death” and expressed his eagerness to “convert the Bolsheviks, like so many Christian knights by the walls of Jerusalem”. Notwithstanding his sometimes-strained relationship with Lensen, he still considered him his friend. Sajer described Lensen’s horrific death under the tracks of a Soviet T-34, which he found fitting, at least in terms of where it took place, ergo, he died in defense of his ancestral home. In Sajer’s accounting, there was no bitterness towards the proud Prussian. It was also during this fighting in East Prussia that Sajer introduced the civilian problem in terms of their pell-mell flight from the Soviets, which complicated the military preparedness to meet them.

Sajer and his compatriots continued to fight a rearguard action and were pushed back in horrific fighting to Memel (now Klaipėda) where they were organized as a defensive barrier to allow the terrified civilian population to escape by ship through Memel’s port on the Baltic Sea. Memel, while not the last battle in which Sajer fought, was the most defining for him. The scene he paints is one of terror. The civilians and the soldiers alike knew what the Soviets would do to them if they were captured — tales of the indiscriminate torture, murders, and rapes (such as the Nemmersdorf massacre by Red Army soldiers in October 1944) were already circulating throughout the civilian populace seeking to flee the Soviet menace.

If they only knew how bad it would be. Some two million Germans lived in East Prussia and had been there for more than six hundred years since the age of the Teutonic Knights — in cities such as Danzig, Königsberg, and Memel — and the entirety of their history, homes, and heritage would be wiped out after the Second World War. Most of the German inhabitants, which then consisted primarily of women, children, and old men, managed to escape the Red Army as part of the largest exodus of people in human history: a population that had stood at 2.2 million in 1940 was reduced to 193,000 at the end of May 1945

After holding the Russians back in vicious and heroic fighting — long enough for almost all the civilians to escape — Sajer, Hals, and a few others made for the docks. It was then under constant aerial bombardment and the Soviets had breached parts of the city. Sajer and the others embarked in a makeshift raft into the icy Baltic, where they were picked up by a passing ship. They made their way to yet another East Prussian town just north of Danzig. There the soldiers experienced a few days of relative recovery but another siege, like that of Memel, was imminent and the evacuation of civilians continued as it had in Memel. Here, Sajer and his group meet the last officer that will demand military rigor of them — and instead of frustration at his insistence, the group was heartened by a relative return to military decorum and order. The evacuation here, however, happened by foot over the frozen Baltic Sea and intermittent isthmus. Civilians and troops marched about twenty-five miles to Danzig over the frozen sea while Soviet bombers dropped bombs to break up the ice to drown them. Once in Danzig, they expected another round of defense and a fight to the death protecting the evacuation, but they received orders to depart to the west. Still fighting until the very end in Danzig, Sajer, Hals and those remaining alive in the Großdeutschland depart for occupied Denmark.

When they landed during the spring of 1945, they are shocked to learn, after making their harrowing seaborne escape, that the Americans and British — and the French — are moving through Germany in a western assault. While the reasoning behind Sajer’s enlistment into the German army was not made explicit, it was cemented and justified by his belief that France would eventually join the Germans in their fight against the Soviets. He believed that Germany was protecting Western Europe by attacking the Soviet Union. At the beginning of Sajer’s long march back to Germany from southern Russia, he continually believed that the French “were already on their way. … The first legionnaires had already set out” to assist them from the mounting Russian onslaught. Sajer thought that Germany and France had established a collaborative government such that the French would be used in the fight against the Soviets. And while thousands of French enlisted to help the Germans, Vichy France remained aloof. He felt as if he had been “betrayed” by France, but the thought of possibly having to kill his fellow countrymen seemed unimaginable to him.

Once in the West, yet another reorganized group of soldiers was formed to resist the Allies, but they were soon captured without any resistance. Each soldier was interrogated, and Sajer’s particular case caused consternation because he was initially deemed a traitor to France but then he was simply allowed to walk away as a liberated French citizen. How or why the Allies changed their minds is never explained. He left the prison yard in a jumble of emotion — so much the more that he did not get to say goodbye to Hals or his other compatriots. His journey home was surreal. His family, after many months of no contact, could not believe that their son had arrived home. As if they understood, Sajer did not speak of the war, nor did his family ask him of it. He joined the French army to rehabilitate his legal standing but was discharged after ten months due to illness. The book ends poignantly enough — in attending a “victory” parade in Paris as a now-French soldier — Sajer recounts silently to himself the memorial of all of the German dead that he had known. To these, he adds one more name — that of Guy Sajer — who too must die as if he lost his life on the Russian Steppe. With no apology or equivocation, he concludes his story.

Reception

It is a mistake to use intense words without carefully weighing and measuring them, or they will have already been used when one needs them later. It’s a mistake, for instance, to use the word ‘frightful’ to describe a few broken-up companions mixed into the ground: but it’s a mistake which might be forgiven. I should perhaps end my account here, because my powers are inadequate for what I have to tell.

The Forgotten Soldier is universally considered one of the best accounts available of the German experience on the eastern front. Sajer’s description of the conflict captures its brutality and its harshness — all in a visceral and authentic voice. He is fearless in what he recounts — documenting the summary execution of partisans and Russian POWs as well as the fear and disorder on the German side. He captures the war in the east in an almost completely unvarnished way — with virtually no effort to sanitize the conflict. Its believability and realism are augmented by his mode of relating the conflict. He hides nothing from his reader — including his refusal to apologize for his involvement. It must be that any soldier’s story, such as this one, endears the reader to the side that the soldier fought on — maybe that is why, more than anything else, this book is hated by some. What is more, Sajer, or at least it seems to me, did not write a book with an agenda beyond telling the story of the men with whom he fought, suffered, and died. His agenda is the story — so that it can be known, and their valor and sacrifice are accorded the recognition that is almost always deprived of the losers in war. In that way, The Forgotten Soldier is a living memorial etched in words to a forgotten generation of men who gave everything for their country — and then some.

While it has similarities to All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque in that All Quiet captured the brutality and horror of mechanized modern warfare from the perspective of a young German soldier on the losing side, Remarque wrote his book soon after the war and appeared to have an anti-war agenda in writing it. Sajer’s book is worse — more horrible and more gut-wrenching — and yet even though Sajer is appalled by what happened to him and his fellow soldiers, there is no anti-war agenda per se. All of it is still too raw for him as if he was still shellshocked twenty years after to think in those terms. And if his account was even half-true, his shellshock was well deserved. He seems to want nothing more than for us to listen to him relating what happened. His book humanizes the man and simply does not permit us to “otherize” the German soldier as something less than human. For all of the conjecture that the German soldier was more machine than man, Sajer is proof positive that this idea is nonsense. They lived and died like anyone else; they dreamed of seeing their parents and their sweetheart like anyone else; they bled and cried like anyone else; they were hungry and cold like everyone else; they prayed for victory like everyone else; and they were bewildered and crestfallen in defeat like anyone else.

The Forgotten Soldier is also compelling because it is a coming-of-age story in a context that few can imagine. He developed from a naive youth to a hardened combat veteran through his experience in uniform over the war. During his first few weeks, Sajer’s “knees trembled, and [he] dissolved in tears. [He] could no longer grasp anything that was happening to [him].” By the end of the war, he was a rugged veteran who fought for survival like a wild beast. He survived, in part by luck, but also because, “[w]e fought for reasons which are perhaps shameful, but are, in the end, stronger than any doctrine. We fought for ourselves.” I have always wondered what the German retreat from the highwater mark of the German occupation of Russia must have been like. Through Sajer, I feel like I have a very good idea and it is more terrible than anything I ever imagined.

There are so many other themes and motifs that I could touch upon that are related to what is essentially a survival tale of epic proportions. The will to live, which far deeper than we can imagine; the loss of innocence of a sixteen-year-old boy in a way that is different from moral failings but just as tragic; the destructive futility and inhumanity of modern warfare; the sheer terror of fear; the despair of facing imminent death and surviving only by blind chance; the vacillation between cowardice and heroism; the cold, the hunger, and the exhaustion of the Russian front and the limits of the human body; Russia herself — her endless steppe that stretches beyond the horizon in a treeless mirage of desolation and expanse; and the meaning of the German defeat for the world that we all now take for granted. All of these themes are present in this book — all of the themes could be unpacked over a lifetime.

* * * *

Only happy people have nightmares, from overeating. For those who live a nightmare reality, sleep is a black hole, lost in time, like death.

Notwithstanding my praise for this book — mine and many others — there are still more who hate it. For my part, the disrepute that some have lobbed at The Forgotten Soldier has more to do with ideologies today than it does Germany during WWII. The first is obvious — it is unapologetic of the Wehrmacht, and, to a lesser extent, it is conspicuously silent on Hitler and the Third Reich. Sajer treats the German army and the Third Reich no different than any other losing army and nation in history. There is no odium attached to any of it — other than the senseless carnage that is war. More than that, there is a sense of pride in Germany — a genuine affinity on the part of the author for Germany, its people, and the honor of its fighting men during World War II. Sajer epitomizes a pan-European consciousness even if he never articulates it as such. He grasped that, even as a French citizen, he was part of a broader European civilization. His actions on the field of battle were the greatest proof of that hidden conviction. While it is far from propaganda, the book feels like propaganda for a generation that has been taught to demonize Germany.

In other words, his non-demonization feels like exultant praise. Throughout, even if there is not an explicit defense of the German cause per se, there is a defense of the German soldier almost without equivocation. It is as if he wanted to avenge himself upon every sleight and calumny ever lodged at the rank-and-file soldiers of the Wehrmacht. He writes: “throughout the war, one of the biggest mistakes was to treat German soldiers even worse than prisoners, instead of allowing us to rape and steal — crimes which we were condemned for in the end anyway.” The implication here is obviously that the German soldiers did not rape, steal, and murder with impunity — at least in any systematic way similar to what the Red Army did across eastern and central Europe. Considering that a wide swath of the public believes — and is taught to believe — that German soldiers were active extensions of genocide and slaughter, this defense of Wehrmacht must be like nails on a chalkboard for certain types of modern intellectuals.

The second is also obvious — the Jews are virtually never mentioned. Twenty years after the war, the author must have known about the atrocities committed against the Jews but there is no mention at all of the Holocaust. Nor is there any mention of the racism of the Nazis. The closest Sajer comes to acknowledging the Jews at all is rather oblique: he mentions sightseeing in Poland during his initial training and writes, “[o]ur detachment goes sightseeing in the city, including the famous ghetto — or rather, what’s left of it. We return to the station in small groups. We are all smiling. The Poles smile back, especially the girls.” It could be — and I think this is the most probable explanation — that Sajer’s experience did not overlap with the Jews in any meaningful way, and he never witnessed any atrocities against them. But if one wants the story to be one unrelenting narrative about the Jews, the omission of them is especially galling because, after all, most now think that World War II was about the Jews. Parenthetically, we tend to think of the U.S. Civil War similarly since it is reduced, almost wholly, to that of slavery. As such, just with the Civil War, we lose sight of the other facts that motivated the Second World War, and we turn people and causes into gross caricatures. The invisibility of the Jews is unforgivable to modern ears, as is the implication that Sajer never witnessed any abuse directed at them by German soldiers. The current gloss, of course, is that the Soviet war was one, long premeditated German pogrom masquerading as an invasion. That Sajer never sees or reports this type of activity is so disconcerting to some that it is to call into question the entire authenticity of his account.

There have been written seemingly hundreds of books about the Holocaust and the suffering of the Jews during World War II; it has become the central defining aspect of modern Judaism. Without debating it, I am reminded of Professor Norman Finkelstein’s controversial work, The Holocaust Industry: Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering. Finkelstein, a Jew and child of concentration camp prisoners noted that the Holocaust has become the predominant theme in American cultural life — one in which the Holocaust now is treated alone in its utter uniqueness as a mystical measure of human suffering and that the Holocaust casts the Jews as always and everywhere as victims of historical antisemitism that reached its climax during World War II. It doesn’t matter that other groups of human beings have suffered similarly throughout history — the Holocaust is a singularity. To write a book that recounts three years in Russia where the Holocaust was, as we have been taught, raging and never mention the Jews is inexplicable to most modern readers.

I do not begrudge anyone writing to document their particular story — or the story of their people. With that same latitude, it seems to me a book that captures the suffering of the German soldier and the German civilian during World War II is something long overdue. Not every book that is written on the fall of the Ottoman Empire during World War I must mention the Armenian genocide; similarly, not every book on World War II must preoccupy itself with the Jews. Sometimes it is OK if another people’s grief and sorrow take center stage even if those people were fallen human beings, like everyone else.

The third is related — his description of the Soviets generally and partisans in particular. If one remembers that most of academia was — and remains — sympathetic to communism, the Soviet Union can never be vilified in the same way that the Third Reich is vilified. True enough, they may concede that it was an experiment that failed on the margins but never in its “laudable” aims, which remain quintessentially moral. Sajer’s description then of Soviet brutality has a mark of inexcusable temerity that is most unwelcome for academics who despise Germany and Nazism. Indeed, Sajer takes it for granted that the Soviet Union was an evil country, which is something, ironically enough, he never does regarding the Third Reich. Sajer, to his credit, does not shrink from describing the cruelty meted out to certain Soviet POWs or captured partisans. Sajer does not claim, however, that such treatment was ordinary or practiced widely. But he describes certain treatments that were understood: for example, Soviet prisoners who stole from the bodies of dead German soldiers were summarily executed. He recounts one such gruesome abuse as follows: “the hands of three [Soviet] prisoners [were tied] to the bars of a gate. … [The German soldier] stuck a grenade into the pocket of one of their coats. … The three Russians, whose guts were blown out, screamed for mercy until the last moment”. This type of despicable activity should make anyone sick and here Sajer shared the sentiment; he wrote that incidents such as these “revolted us so much that violent arguments broke out between us and these criminals every time.” The element within the Wehrmacht that was cruel and “criminal” towards Soviet POWs often claimed that they were giving to the Soviets what the Soviets were giving to German POWs. Sajer rejected those claims categorically, “Russian excesses did not in any way excuse us for the excesses by our own side.”

But the broader point, and I think this is understandable assuming the veracity of the account, Sajer describes the Soviets and the Soviet Union as something barbaric and ugly. The conception of the enemy generally leaks over with the conception of the Russians in particular. I think all wars tend to make soldiers dehumanize the army opposing them and Sajer is unexceptional here. His hatred towards the partisans, which was still simmering many years after he was driven from the Soviet Union, is more difficult to understand and more objectionable to modern readers. After all, even from a quasi-objective point of view, the “partisans” were ordinary people resisting an invading army. That Sajer never mentions the systematic abuse of the Russian populace during the occupation or retreat by the German army is something certain critics cannot stomach — especially when Sajer spills much ink on the systematic abuse by the Red Army of the German populace in East Prussia. Not only does the mention of suffering by “guilty” German civilians rankle some; a corresponding omission of suffering by “innocent” Soviet civilians is unforgivable. Modern critics believe, like an article of faith, that the German army committed atrocity after atrocity in the U.S.S.R. — that Sajer mentions none is something that cannot be believed.

The critics of this book — for many of the reasons just mentioned — have attacked it not so much on moral grounds but on its veracity. I suppose that makes sense: if it were a verifiable account, the only argument against would be, “I don’t like it,” which is not an argument at all. So, some have argued that Sajer made it up — maybe he was in Russia for a time, maybe not, but the experiences recounted are largely the stuff of fiction. I won’t debate that beyond noting that others have responded to the alleged proofs of the fictionalized The Forgotten Soldier and offered counter-narratives why it is more likely than not an authentic story. For his part, Mouminoux contended it was authentic but admitted that it was never meant to be a chronological retelling of his time in Russia. He admitted that he may have gotten some details wrong in his memory. The records of the German army, especially later in the war, are in shambles or non-existent. There is no way to prove the argument one way or the other. That said, it struck me as an authentic story — and German veterans from the eastern front have also said that it struck them as consistent with their experiences.

In that sense, does it matter? If Mouminoux wrote what is, at worst, alleged to be a novel, it is a brilliant historical novel that aligns with the experiences of verifiable veterans who were there. Should it matter to me if Guy Sajer was there? Great Memoirs and novels have the power to move us — either way, The Forgotten Soldier is such a book.

Conclusion

Abandoned by a God in whom many of us believed, we lay prostrate and dazed in our demi-tomb. From time to time, one of us would look over the parapet to stare across the dusty plain into the east, from which death might bear down on us at any moment. We felt like lost souls, who had forgotten that men are made for something else, that time exists, and hope, and sentiments other than anguish; that friendship can be more than ephemeral, that love can sometimes occur, that the earth can be productive, and used for something other than burying the dead.

While I became enraptured by this story for the sake of the men involved, God was never far from me or them. Sajer was wrong: he and his fellows were never abandoned. Christianity, much like the Jews, is not a significant part of The Forgotten Soldier. Besides a lustful Catholic chaplain who carries on with a local girl as almost a stock comical character, there is no prayer to speak of and no mention of Divine Providence, one way or another. Our Lord’s name is used in vain throughout. Religious themes and metaphors from our Lord’s Passion are occasionally used to signify the suffering of the soldiers. It is clear that some of the soldiers that Sajer and his friends know are religious and the reason we know that is the occasional abuse that is showered upon such men when they pray instead of act in a given circumstance. But this book is not particularly interested in God. In that sense, it is a thoroughly modern book.

National and international socialism, i.e., Nazism and Soviet communism, were developments of the modern era that had thoroughly rejected God. The war in the east, ironically enough, was fought between two largely atheistic ideologies by many men who carried with them the simple faiths of their Catholic, Orthodox, or even Protestant families. Patriotism and duty — and lest we forget, state compulsion — were more compelling than Mein Kampf or The Communist Manifesto. The faith passed out of Europe much like it passed out of the Holy Land — and the disappearance of both came because the people were faithless, obstinate, and licentious. By the time World War II began, the faith in Europe had largely disappeared from the agendas and ideologies of secular nation-states. The elites of European society became apostates long before their fellow ordinary citizens ever did. Pockets of faith remain, and they remain today, but Europe, at least in terms of its faith, has been in an accelerating process of religious ossification for a long time. Places of faith have slowly been transformed from central loci of community and spiritual life to museums of a dead cult. The Forgotten Soldier then does not have an agenda per se with God; it simply reflects the accumulated and rotten milieu of several generations of men raised without a sense of public and private faith.

One hundred and fifty years after the French Revolution and fifty years after Otto von Bismarck’s Kulturkampf against the Catholic Church, is it really surprising that we see German soldiers who reflect irreverence and irreligiosity? And even if I have been sensitive to German civilization and German sufferings throughout this essay, and even if I believe that the Soviet Union was more objectionable than the Third Reich (and I do), the reality is that Nazism was an attempt to reconstruct a neopagan cult of ethnos that failed to honor the True God. While my mind has been changed — and I have been red-pilled, as it were — on the question of ethnic and racial homogeneity and its relationship to stable political order, the reality is that ethnos without some correspondence to a cult — and the True cult — is a half-measure that must inevitably fail.

Setting aside the neo-paganism, before we simply condemn the German aspiration of a Germany peopled and ruled by Germans, as articulated by the National Socialists, we should pause to consider whether we are throwing the baby out with the bathwater. The Nazi Party platform, mentioned above concerning the Treaty of Versailles, endorsed a coextensive political state that corresponded with the “racial” elements of Germans. In other words, the Nazis wanted Germany to be populated by citizens who were German. They were:

- None but members of the nation may be citizens of the state. None but those of German blood, whatever their creed may be. No Jew, therefore, may be a member of the nation.

- Whoever has no citizenship is to be able to live in Germany only as a guest and must be regarded as being subject to foreign laws.

- The right of voting on the state’s government and legislation is to be enjoyed by the citizen of the state alone. We demand therefore that all official appointments, of whatever kind, shall be granted to citizens of the state alone. We oppose the corrupting custom of parliament of filling posts merely with a view to party considerations, and without reference to character or capability.

- We demand that the state be charged first with providing the opportunity for a livelihood and way of life for the citizens. If it is impossible to nourish the total population of the State, then the members of foreign nations (non-citizens) must be excluded from the Reich.

- All immigration of non-Germans must be prevented. We demand that all non-Germans, who have immigrated to Germany since 2 August 1914, be required immediately to leave the Reich.

- All citizens of the state shall be equal as regards rights and obligations.

Contained within this portion of the platform is the idea that ethnic homogeneity, territory, and sovereignty ought to converge in political reality. This type of platform is, of course, anathema to the modern, globalist Americanist ideology today, but, ironically enough, these six planks of the Nazi platform essentially mirror the modern state of Israel’s Jewish political character. In particular, the so-called legal “right of return” for any Jew to acquire Israeli citizenship and the express adoption in 2018 in law that Israel is defined as a nation-state for the Jewish people has a remarkable degree of concurrence with the National Socialist view that Germany ought to be defined as a nation-state for the German people. It is absurd to suggest that this aspiration was per se immoral — the aim of cohesion between state and people politically is only alleged to be immoral when a person of European stock suggests it for their people.

Many would be grievously offended by my comparison of Israel to the Third Reich but my point, and it should be obvious, is that there are countries today that pursue the same type of folkish policies — namely Israel — that tie a land to exclusively to a people. And I agree with that idea more and more, i.e., “blood and soil” has a currency in my life that it never did before. To the extent that it makes me liable to the charge of intellectual Nazism (which is ridiculous), it makes me equally liable to the charge of Zionism. It is no thought crime in the United States to support Zionism as it relates to the Jews in a sliver of land that borders the Mediterranean Sea; likewise, it should not be a thought crime to support the similar idea that European peoples too ought to have a political state tied to the land and their particular people and culture. One cannot be simultaneously a “beyond-the-pale” racist and a wonderful person for espousing the same idea. I refuse to abide by such cognitive dissonance. For my part, however, the ambition to preserve the culture, language, and the stock of a people is reasonable but without Catholicism as its animating soul, it becomes just another idolatry (viz., the idol being the folk themselves). Preserving a people without preserving their souls in the True Faith is a futile project of which I want no part.

And what we see in the suffering of the German soldiers on the eastern front through Sajer is misery and anguish without God and reason. True enough, the ghosts of duty and history animate them. The notion of patriotism motivates them. And the awful specter of fear and death move them. But their suffering is rooted in the dirt of this world — it is materialist and crimped. A man with faith — who fights for faith alongside kith and kin — dies differently than a man merely avoiding death for an idea of this world. Both can be heroic, but the effect of heroism is very different on them. The soldier with faith is immune to cynicism; the soldier without faith becomes overwhelmed by it. Ultimately this is why The Forgotten Soldier is ultimately a secular school of suffering and cynicism that destroys the heart. Suffering for an idol — a false god — is something that eventually destroys man’s natural religious inclinations to look and find the True God. Suffering, which is man’s lot, is either suffered unwillingly and angrily or is suffered willingly and meekly. It is either redemptive if it is fused to the Cross of our Savior or it is destructive if it is fused with anything else. For both, it is always endured reluctantly but only Christianity provides an understanding of this human constant and mystery that makes more than sense — it transforms it. We all suffer. The vital question is how we are shaped by it. The men of The Forgotten Soldier were destroyed by their suffering — in a context of a war that destroyed everything else. Germany is a place, and the Germans are a people, but neither can supply the transcendent reason for suffering adequately. No country or people can.

That I have a different view of World War II — and who its villains and heroes were — does not mean that I condone the idol of race or ethnos. If Germany embraced a racial idol while pursuing otherwise sensible policies of economics, foreign policy, and immigration, I do not condone their racial idol. They failed, at least in my estimation, because of the delta that existed between the principles of their racial idol and the True Faith. For my part, I see the value of homogeneity and the political state but what is more important to me is that the state be true to God. The two need not be mutually exclusive despite the liberal rot within the Church that claims otherwise. It is a false choice between Americanism and Nazism — we Catholics ought to strive for something better. I suppose the difference between my view and that of the conventional demonization of Germany is that I choose to splice the good and the evil from the Third Reich, just as I do the same for the Allies. The “Axis” and the “Allies” are not talismanic terms that confer the magical properties of good and evil. And even if I abhor many policies pursued by the German government during the Nazi era — like, for example, the liquidation of the “useless bread gobblers” or the forced deportation and migration of the Jews and Gypsies which led to their wanton destruction, among many others, that resulted in the deaths of millions — I choose to take a wider view of the historical contest that existed then and exists now. That wider view is what intellectuals do in every other context of history.

* * * *

Peace has brought me many pleasures, but nothing as powerful as that passion for survival in wartime, that faith in love, and that sense of absolutes. It often strikes me with horror that peace is really extremely monotonous. During the terrible moments of war one longs for peace with a passion that is painful to bear. But in peacetime one should never, even for an instant, long for war!

The paradox of an experience, like the one recounted in The Forgotten Soldier, is the dual recognition that life during the crucible was hellish, but, at the same time, it was the only time that such men felt alive. He captures this dilemma well — no one should long for war but there is a vitality of life that throbs when life itself hangs in the balance in a real and unrelenting way. Parenthetically, this is why young men often seek out dangerous activities gratuitously. What makes all of this horrible — what makes it abusively horrible — is that the men of Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS who survived the ordeal of Russia never had a country to which they could return. I am not discussing here things like the aged veterans gathering for the dedication of a war memorial or gathering for drinks at the equivalent of the VFW. No, these men had to endure silence and shame and a refusal to acknowledge their sacrifice. Even if the post-war German bureaucracy accorded some of them pensions for time served, the shame of the war imposed by the Allies created something that made their sacrifice border on dishonorable.

By contrast, the American South, which was similarly smashed as a nation, managed to honor its war dead and surviving veterans as taking part in something honorable even if defeated. It was only until the United States lost its mind — well into the twenty-first century and long after such veterans were dead — that such monuments and memorials were pulled down to satiate an irreverent and evil mob. There was no “lost cause” in Germany and no honor was given to these men who sacrificed enormously. Wesreidau’s comments to his men then proved prophetic when he said, “With our deaths, all the prodigies of heroism which our daily circumstances require of us, and the memory of our comrades, dead and alive, and our communion of spirits, our fears and our hopes, will vanish, and our history will never be told. Future generations will speak only of an idiotic, unqualified sacrifice.” Sajer did what he could to tell their history.

* * * *

I had often thought that if I managed to live through the war I wouldn’t expect too much of life. How could one resent disappointment in love if life itself was continuously in doubt? Since Belgorod, terror had overturned all my preconceptions, and the pace of life had been so intense one no longer knew what elements of ordinary life to abandon in order to maintain some semblance of balance. I was still unresigned to the idea of death, but I had already sworn to myself during moments of intense fear that I would exchange anything — fortune, love, even a limb — if I could simply survive.

Guy Mouminoux may have traded any semblance of a normal life to just survive World War II, but he did something much more. As someone who participated from outside of Germany, he was uniquely able to pay homage to these men. For all of the hatred and bile poured upon Germany for almost the full extent of the twentieth century, Sajer did something that bucked the trend: He said enough and told his story.

Saint Boniface, pray for us.

Stars and trees seen from Luhasoo bog in Estonia (

Stars and trees seen from Luhasoo bog in Estonia ( Small tortoiseshell butterfly on the concrete of a car-park, Dorset, England (

Small tortoiseshell butterfly on the concrete of a car-park, Dorset, England (

Bestial Black Rapist #2:

Bestial Black Rapist #2:  Bestial Black Rapist #3:

Bestial Black Rapist #3: