Doused and Denounced

Orwellian–screenshot from academic data bases holding Prof. Wolters’ un-PC AHR review https://t.co/ZRz47T4Vb0 pic.twitter.com/Z2N2ympePp

— Virginia Dare (@vdare) June 6, 2017

A cold civil war has been brewing within academe, a war between “biologians” and “culturists.” Many modern biologists, genomic scientists, and physical anthropologists are biologians. They think evolutionary adaptations are partly responsible for some racial disparities. On the other hand, most historians, social scientists, public leaders, and mainstream journalists are culturists. They minimize the importance of biology and evolution and say that history and culture explain the variations in the distribution of human characteristics.

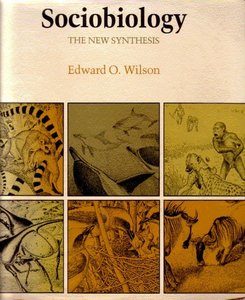

One of the landmark events in this academic civil war occurred in 1975, when E. O. Wilson, a biology professor at Harvard, published Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Professor Wilson presented a mountain of evidence to establish that biology influenced many forms of social behavior in the animal kingdom. Then, in the last chapter of the book, Professor Wilson maintained that this was also true for human beings.

Among biologists, the initial reaction to Sociobiology was overwhelmingly favorable. The response of many historians and social scientists, however, was quite critical. This was not surprising, for most historians and social scientists regard human nature as relatively unaffected by our evolutionary past, as something that is shaped by social forces. Some scholars, especially those with Marxist beliefs, have emphasized the special importance of economic forces that are extraneous to human biology.

As it happened, a Marxist group at Harvard, Science for the People, responded to Sociobiology with printed leaflets and teach-ins that were harshly critical of Professor Wilson. For a few days a protester in Harvard Square used a bullhorn to demand that the university fire Professor Wilson, and on one occasion two students invaded the professor’s class on evolutionary biology to shout slogans and deliver anti-sociobiology monologues. To make matters worse, Professor Wilson received little support from his colleagues on the Harvard faculty, and to avoid embarrassment he stayed away from department meetings for an entire year.

Professor Wilson considered offers to move to other universities, but he decided to stay at Harvard. “The pressure was tolerable,” he has written, “since I was a senior professor with tenure . . . and could not bear to leave Harvard’s ant collection, the world’s largest and best.”

The opposition reached something of a climax in 1979, when Professor Wilson was scheduled to speak at a meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. As he sat at a table near the lectern, a young man from the audience grabbed the microphone and harangued the assembled scholars. A young woman then poured a pitcher of water over Professor Wilson’s head and demonstrators chanted, “Wilson, you’re all wet,” and “Racist Wilson, you can’t hide. We charge you with genocide.”

Despite the vilification he received in the 1970s, things eventually turned out well for Professor Wilson. By the turn of the twenty-first century, he was widely celebrated as the pioneering founder of two new academic fields, the evolutionary biology of humans and evolutionary psychology. He was the author of two Pulitzer Prize-winning books, and he received many academic awards. When Harvard University Press published a twenty-fifth anniversary edition of Sociobiology in 2000, it was evident that Professor Wilson’s theory appealed to many of the best minds in science. By then Amazon.com listed 416 titles under “sociobiology” and 1, 218 under “human evolution.”

Nevertheless, as I have recently learned the hard way, many historians know little or nothing about sociobiology, evolutionary biology, or evolutionary psychology.

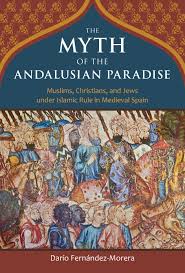

The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise:

The Myth of the Andalusian Paradise: