Chapter 10 of “Our Vision for America — Common Sense Revisited”: Immigration/Race

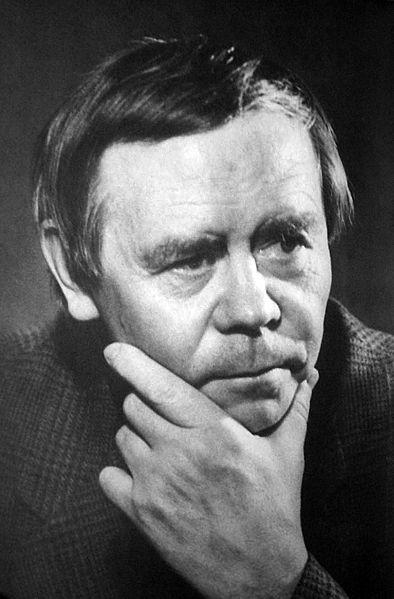

Our Vision for America: Common Sense Revisited is a book-length position statement by Merlin Miller, presidential candidate for the American Third Position Party; Adrian Krieg, Board Member of the American Third Position, is co-author. The book may be ordered for $9.95 here (see also below). The A3P is currently recruiting activists to work on the campaign. Chapter 10, “Immigration and Race,” is reprinted here by permission.

“…those who acquire the rights of citizenship, without adding to the strength or wealth of the community; are not the people we are in want of.” James Madison

Immigration. Enough is enough.

Both political parties have been kicking the can of immigration down the street for years. All they have done is to propose amnesty for 24 million illegal aliens, which costs our nation, as well as individual states, billions of dollars. Additionally, we have over 50,000 illegal aliens who are convicted felons, and cannot be located.

During the 1960’s, our immigration system was transformed to favor persons from Third World countries incapable of assimilating into any European homeland. If current demographic trends continue, our people will become a minority in America within only a few decades. The vast majority of immigrants, both legal and illegal, come from nations in Latin America, Asia and Africa lacking in education, science, art, law, governance or industrial achievements in any way comparable to ours. Numerous studies have confirmed that there is no net economic benefit to the U.S. economy from Third World immigration due to the added costs of education, infrastructure, health care, welfare programs and law enforcement.

I view controlling global elites as spoiled, cruel children, rather than as the Gods they think themselves to be. An elite child might look at America, as one might an ant farm, containing a large homogenous colony. With self-absorbed malignancy, this child might throw in a large quantity of another ant species to compete for the farm’s limited resources. He adds another and then another, watching with cruel intent as the ants begin to fight. The global elites, through policy control and media, are doing this to America and we must now be alert for racial “false flags” – as this child prepares to “shake the ant farm”. Let us break the glass and allow the ants to repair to their natural colonies.

A3P’s will implement sensible immigration policies, which respect what is best for America and our native citizens and not what the UN dictates to our State Department in their advocacy of massive 3rd world immigration. We will not tolerate the continued demographic destruction of America, while our politicians and media encourage and lie about it – which they have done since at least 1965…

First, our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. Under the proposed bill, the present level of immigration remains substantially the same…. Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset…. Contrary to the charges in some quarters, [the bill] will not inundate America with immigrants from any one country or area, or the most populated and deprived nations of Africa and Asia…. In the final analysis, the ethnic pattern of immigration under the proposed measure is not expected to change as sharply as the critics seem to think…. The bill will not flood our cities with immigrants. It will not upset the ethnic mix of our society. It will not relax the standards of admission. It will not cause American workers to lose their jobs.

-Senator Ted Kennedy, speaking to the Senate regarding the introduction of the Immigration Act of 1965 Read more