Mark Rothko, Abstract Expressionism and the Decline of Western Art, Part 3

Abstract Expressionism and the Culture of Critique

Abstract Expressionism was disproportionately a Jewish cultural phenomenon. It was a movement populated by legions of Jewish artists, intellectuals and critics. Prominent non-Jewish artists within the movement like Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell married Jewish women (Lee Krasner and Helen Frankenthaler). Willem de Kooning defied the trend, although he generally had to ingratiate himself with the overwhelmingly Jewish intellectual and cultural elite focused around the journal Partisan Review which was ‘dominated by editors and contributors with a Jewish ethnic identity and a deep alienation from American cultural and political institutions.’[i]

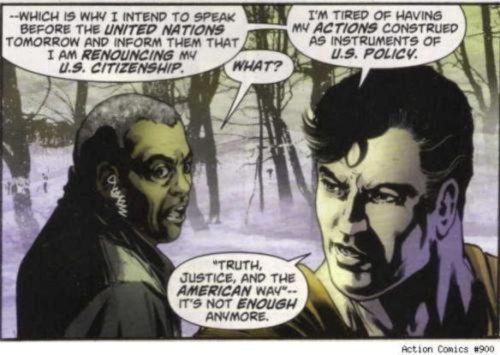

It was an art movement where the culture of critique of Jewish artists and intellectuals, frustrated that the post-war American prosperity based on Keynesian foundations had prevented the coming of socialism, turned inward and instead “proposed individualistic modes of liberation.” This mirrored the ideological shift that occurred among the New York Intellectuals generally who had “gradually evolved away from advocacy of socialist revolution toward a shared commitment to anti-nationalism and cosmopolitanism, ‘a broad and inclusive culture’ in which cultural differences were esteemed.”[ii] Doss notes how this ideological shift manifested itself among the post-war artists who became the Abstract Expressionists:

As full employment returned, New Deal programs were terminated — including federal support for the arts — the reformist spirit that had flourished in the 1930s dissipated. Corporate liberalism triumphed: together, big government and big business forged a planned economy and engineered a new social contract based on free market expansion… With New Deal dreams of reform in ruins, and the better “tomorrow” prophesied at the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair having seemingly led only to the carnage of World War II, it is not surprising that post-war artists largely abandoned the art styles and political cultures associated with the Great Depression.[iii]

The avant-garde artists of the New York School instead embraced an “inherently ambiguous and unresolved, an open-ended modern art … which encouraged liberation through personal, autonomous ‘acts’ of expression.” The works of the Abstract Expressionists were “revolutionary attempts” to liberate the larger American culture “from the alienating conformity and pathological fears [especially of communism] that permeated the post-war era.”[iv] Rothko claimed that “after the Holocaust and the Atom Bomb you couldn’t paint figures without mutilating them.” His friend Barnett Newman remarked that if people only read his paintings properly “it would mean the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism.”[v] Read more