Evil Genius: Constructing Wagner as Moral Pariah—PART 3

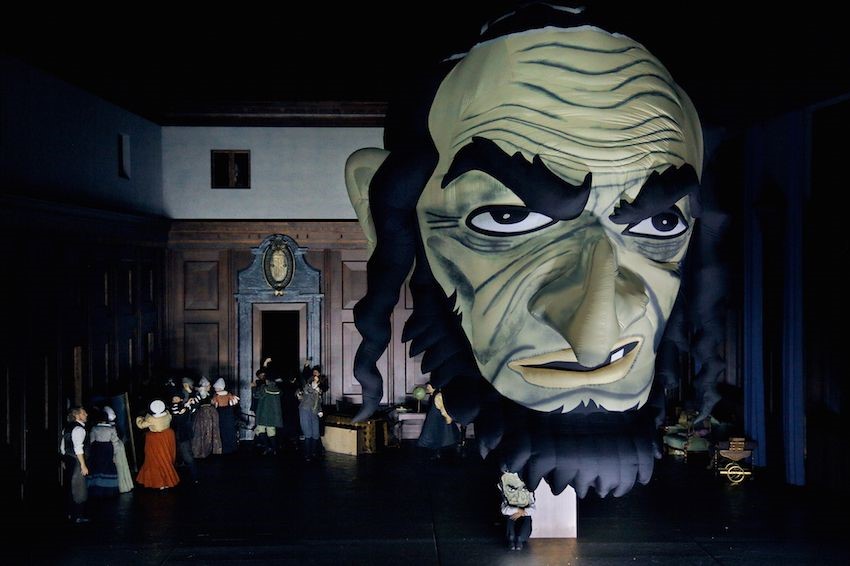

Scene from Barrie Kosky’s 2017 Bayreuth production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg with an outsize image of Beckmesser, the putative Jew

Wagner’s Music Dramas as Coded Anti-Semitism

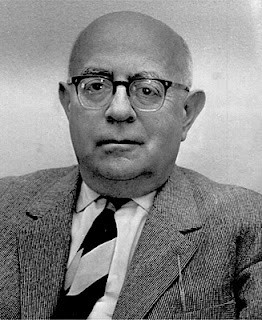

T.W. Adorno and Wagner biographer Robert Gutman began a modern Jewish intellectual tradition when they proposed that Wagner’s antipathy to Jews was not limited to articles like Judaism in Music, but included hidden anti-Semitic and racist messages embedded in his operas. Numerous Jewish writers have taken up this theme and encouraged audiences to retrospectively read into Wagner’s operas latent signs of anti-Semitism. The gold-loving Nibelung lord Alberich in Siegfried is, for instance, supposedly a symbol of Jewish materialism. Solomon writes that Alberich is clearly “the greedy merchant Jew, who becomes the power-crazed goblin-demon lusting after Aryan maidens, attempting to contaminate their blood, and who sacrifices his lust in order to acquire the gold…”[1]

Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (originally written in 1845), is frequently touted as his most anti-Semitic opera. The character Beckmesser, who is incapable of original work and resorts to stealing the work of others, is said to symbolize the lack of Jewish originality that Wagner highlighted in Judaism in Music. According to Gutman, Beckmesser was modeled after Eduard Hanslick, the powerful half-Jewish music critic who constantly disparaged Wagner. Beckmesser purportedly draws directly on a common fund of nineteenth-century anti-Semitic stereotypes: he shuffles and blinks, is scheming and argumentative, and is not to be trusted. He slinks up the alley behind the night watchman in Act II, and limps and stumbles about the stage in Act III, blinking with embarrassment when Eva turns away from his ingratiating bow at the song contest. Furthermore, when he sings, he wrongly accents certain syllables and sings with disjointed rhythms, parodying the Jewish cantorial style. For British musicologist Barry Millington, the fact that Wagner invested Beckmesser with such traits “is a startling fact that almost of itself provides proof of Wagner’s anti-Semitic intent in Die Meistersinger.”

At the 2017 Bayreuth Festival, Barrie Kosky—the first Jewish director to stage a work at the festival—played up such notions, portraying Beckmesser with stereotypical Jewish features (see the lead photograph). In the production, Kosky embedded the opera’s setting of Nuremberg in the twentieth century as the birthplace of the race laws enacted by the National Socialists, the setting of the NSDAP’s giant torch-lit rallies, and the scene for the postwar show trials of Hitler’s henchmen. Kosky’s “edgy” production won rapturous applause from an audience that included Chancellor Angela Merkel. Spiegel Online called the production “chillingly relevant” in using Wagner’s anti-Semitism to take on “hatred of Jews” in today’s Europe. Die Welt said Wagner’s “toxic ideology” had always been an “elephant in the room” which Kosky had ingeniously opted to make “the actual subject of his staging.”

Jewish Opera director Barrie Kosky

Jewish Opera director Barrie Kosky

Like Beckmesser, the characters of Mime in the Ring and Klingsor in Parsifal are also widely identified as Jewish stereotypes, although none of these were actually identified as Jews by Wagner in the libretto. Mime is, for Solomon, depicted by Wagner “as a stinking ghetto Jew” while “Siegfried represents the conscience-free, fearless Teuton, he feels no remorse. … He is glorified as the warrior hero of the Ring, the archetypal proto-Nazi.”[2] Unconcerned at the lack of any real evidence for his thesis, Solomon maintains that virulent racism “permeates all aspects of his music dramas through metaphorical suggestion. Wagner is always just a step away from actually calling his evil characters ‘Jews,’ even though it was obvious to his contemporaries.” He claims that Wagner was too clever to identify Jews in his music dramas, especially after the critical reactions he received to his essay Judaism in Music. “His intent was far more artful and covert, but nevertheless still political: to reach his audience on an emotional, subliminal level, bypassing their critical faculties.” In the final analysis, Wagner’s operas are, for Solomon, “tools of racist, proto-Nazi hate propaganda, written for the purpose of redeeming the German race from Jewish contamination, and for expelling the Jews from Germany.” Moreover, the malign influence of Wagner continues insofar as “the subtext of racist metaphors has not diminished in Wagner’s operas, so they will continue to exert a subliminal influence.”[3]

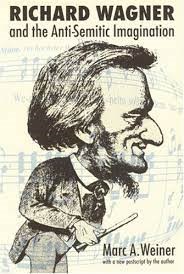

In his book Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination (1997), Marc A. Weiner likewise argued that Wagner deliberately used the characters in his operas to promote his sociological theories of a pure Germany purged of Jewish influence. According to Weiner:

Wagner’s anti-Semitism is integral to an understanding of his mature music dramas. … I have analyzed the corporeal images in his dramatic works against the background of 19th-century racist imagery. By examining such bodily images as the elevated, nasal voice, the “foetor judaicus” (Jewish stench), the hobbling gait, the ashen skin color, and deviant sexuality associated with Jews in the 19th century, it’s become clear to me that the images of Alberich, Mime, and Hagen [in the Ring cycle], Beckmesser [in Die Meistersinger], and Klingsor [in Parsifal], were drawn from stock anti-Semitic clichés of Wagner’s time.[4]

For Weiner, Wagner’s anti-Semitic caricatures can be readily identified from their manner of speech, their singing, their roles, and their body language. “All of the stereotypical cardboard, cookie-cutter features of a Jew … show up all over the place in his musical dramas.” Under Weiner’s deconstruction of Wagner’s characters it emerges that his Teutonic heroes are “invariably clear-eyed, deep-voiced, straight-featured and sure-footed. The Jewish anti-heroes have dripping eyes, high voices, bent, crooked bodies and a hobbling, awkward step, with these embodied metaphors all serving to reinforce the ideology of racism.”[5] In response to Weiner’s critique, one is reminded of the aptness of Goldwin Smith’s remark that the “critics of Judaism are accused of bigotry of race, as well as bigotry of religion. This accusation comes strangely from those who style themselves the Chosen People, make race a religion, and treat all races except their own as Gentile and unclean.”[6]

Viktor Chernomortsev, left, as Alberich and Vasliy Gorshkov as Mime in the Kirov Opera production of Wagner’s “Siegfried” at the Orange County Performing Arts Center in 2006.

Numerous Jewish commentators cite Wagner’s Parsifal, the last of his music dramas, as his most racist opera. Gutman, for example, labels it “a brooding nightmare of Aryan anxiety.” According to Jewish academic Paul Lawrence Rose in his book Wagner, Race and Revolution, Wagner intended Parsifal to be

a profound religious parable about how the whole essence of European humanity had been poisoned by alien, inhuman, Jewish values. It is an allegory of the Judaization of Christianity and of Germany—and of purifying redemption. In place of theological purity, the secularized religion of Parsifal preached the new doctrine of racial purity, which was reflected in the moral, and indeed religious, purity of Parsifal himself. In Wagner’s mind, this redeeming purity was infringed by Jews, just as devils and witches infringed the purity of traditional Christianity. In this scheme, it is axiomatic that compassion and redemption have no application to the inexorably damned Judaized Klingsor and hence the Jews.[7]

This theory sits rather incongruously alongside the fact that when the National Socialists came to power in 1933, Parsifal was condemned as “ideologically unacceptable” and unofficially banned throughout Germany after 1939.[8] In his diaries Goebbels dismissed the opera as “too pious.”[9] If Parsifal truly is the racist opera that Rose alleges, one might have expected it to have been given a place of prominence in the Third Reich.

In Wagner, Race and Revolution, Rose claims the philosophical revolution brought about by Kant in the late eighteenth century was a response to the Jewish Question, with Kant’s transcendental idealism intended as liberation from the shackles of Jewish ways of looking at the world. The corollary of this, for Rose, is that Schopenhauer’s philosophy (with its heavy debt to Kant) is thoroughly infused with anti-Semitism, and, consequently, Wagner’s Schopenhauerian opera Tristan and Isolde is deeply anti-Semitic. Rose proposes that: “Such is the most fundamental anti-Jewish message that underlies the apparently ‘non-social’ and ‘non-realistic’ opera composed in Wagner’s Schopenhauerian phase, Tristan.”[10] Magee trenchantly observes that:

We are no longer surprised when he goes on to tell us that “Hatred of Jewishness is the hidden agenda of virtually all the operas.” It is no good Wagner trying to slip this past Professor Rose by making no mention of it: Rose is not to be so easily fooled. … Rose often sees the omission of any mention of Jews or Jewishness as being due to anti-Semitism, and this enables him throughout his book to expose anti-Semitism in undreamt-of places, in fact in all forms of art and ideas that are not either Jewish or about Jews. … Writers like Professor Rose can be endlessly resourceful in arguing that the apparent absence of something is proof of its presence. … Such a procedure is intellectually fraudulent from beginning to end.[11]

Jewish music critics and intellectuals, like those cited above, have enthusiastically seized upon Wagner’s great-grandson Gottfried for having backed their various theories about the inherently anti-Semitic nature of Wagner’s operas, and Wagner’s firm standing as a moral pariah. Gottfried Wagner has made a virtual career out of attacking his ancestors—constantly denouncing his great-grandfather and other family members as evil anti-Semites. In his book The Wagner Legacy, he declares: “Richard Wagner, through his inflammatory and anti-Semitic writings, was co-responsible for the transition from Bayreuth to Auschwitz.”[12] In writing his Twilight of the Wagners: The Unveiling of a Family’s Legacy, Gottfried Wagner had, according to Solomon, “in an act of self-imposed moral obligation and great personal sacrifice, restored to his roots the conscience that Wagner and Hitler took away.”[13] Gottfried Wagner appeared at a symposium at the American Jewish University in 2010 where he continued “to set the record straight today. Always on the side of the Jews, he stopped off on Shabbos to mingle with congregants at a local temple.”[14]

Despite all the claims made about the allegedly anti-Semitic nature of Wagner’s operas, Strahan points out that it is equally possible to point to cultural references in Wagner’s work that are sympathetic to the Jewish place in European culture. For Strahan, “the hero of the early opera The Flying Dutchman is synonymous with the ‘Wandering Jew,’ the Dutchman’s endless journeying analogous to that symbol of the Jewish Diaspora.”[15] Wagner himself referred to his eminently non-Jewish personification of redemption through love, the Flying Dutchman, as an “Ahasverus of the Ocean.” Despite this, Rose argues that Wagner’s making the Wandering Jew a Dutchman was itself an anti-Semitic act, claiming that: “Wagner’s use of this universalized figure of a wanderer has a profoundly anti-Semitic implication; for Wagner’s heroes—and especially the Dutchman—are able to achieve redemption precisely because they are not Jewish.”[16]

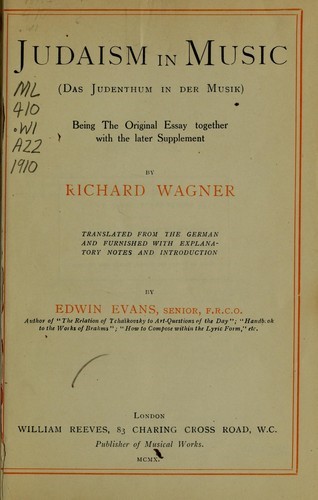

Wagner explicitly states in Judaism in Music that what makes Jews such unsatisfactory characters in real life also makes them unsuitable for representation in art, including dramatic art. He writes:

In ordinary life the Jew, who as we know possesses a God of his own, strikes us first by his outward appearance which, whatever European nationality we belong to, has something unpleasantly foreign to that nationality. We instinctively feel we have nothing in common with a man who looks like that. … Ignoring the moral aspect of this unpleasant freak of nature, and considering only the aesthetic, we will merely point out that to us this exterior could never be acceptable as a subject for a painting; if a portrait painter has to portray a Jew, he usually takes his model from his imagination, and wisely transforms or else completely omits everything that in real life characterizes the Jew’s appearance. One never sees a Jew on the stage: the exceptions are so rare that they serve to confirm this rule. We can conceive of no character, historical or modern, hero or lover, being played by a Jew, without instinctively feeling the absurdity of such an idea. This is very important: a race whose general appearance we cannot consider suitable for aesthetic purposes is by the same token incapable of any artistic presentation of its nature.[17]

In this passage (first published in 1850 and then again unchanged in 1869), Wagner totally rejects the idea of Jews playing characters and characters playing Jews on stage, stating categorically that the Jewish race is “incapable of any artistic presentation of his nature,” and leading into the statement with the words: “This is very important.” Magee notes that here Wagner “positively and actively repudiates the idea of trying to present Jews on the stage; and if we seek an explanation of why he never did so, here we have it.” Wagner would not, contrary to the wishes of many of his friends, have gone out of his way to publish this again in 1869 if, as alleged, he had just done the opposite and made Beckmesser a Jewish character in Die Meistersinger which had premiered the previous year.[18]

Wagner produced thousands of pages of written material analyzing every aspect of himself, his operas, and his views on Jews (as well as many other topics); and yet the purportedly “Jewish” characterizations identified by Adorno, Gutman and countless others are never mentioned—nor are there any references to them in Cosima Wagner’s copious diaries. It can hardly be argued that Wagner was hiding his true feelings for he took great pride in speaking out fearlessly and vociferously on the subject of Jews, and did not worry about offending anyone. None of Wagner’s supposedly obvious characterizations were ever used in the propaganda of the Third Reich. To identify such characters as Beckmesser, Alberich, Mime, Klingsor and Kundry as Jews is, therefore, entirely speculative.

The Jewish pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim makes the point that: “Whoever wants to see a repulsive attack on Jews in Wagner’s operas can of course do so. But is it really justified? Beckmesser, for example, who might be suspected of being a Jewish parody, was a state scribe in the year 1500, a position that was unavailable to Jews.”[19] Barenboim is also quick to point out that Wagner’s anti-Semitism did not prevent his music from being performed by Jews even after Hitler came to power. In Tel Aviv in 1936, for example, the Palestine Symphony Orchestra—precursor to today’s Israel Philharmonic—performed the prelude to Act 1 and Act 3 of Lohengrin under the baton of Arturo Toscanini. “Nobody had a word to say about it,” Barenboim observes. “Nobody criticised [Toscanini]; the orchestra was very happy to play it.”

Arturo Toscanini with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra

Arturo Toscanini with the Palestine Symphony Orchestra

Even Nietzsche, who attacked Wagner on numerous occasions for his personal anti-Semitism, never alleged there was anti-Semitism in the operas. Moreover, the audiences that flocked to Wagner’s works all over the world did not seem to perceive their supposedly obvious anti-Semitic subtexts for, as Magee points out, “in the huge literature we have on the subject, unpublished as well as published, the question arises rarely until the middle of the twentieth century.”[20] For Magee, a great many writers (especially Jewish writers) are simply “swept forward by the momentum of their own anger” into alleging the omnipresence of anti-Semitism in Wagner’s operas. “To a number of them it comes easily anyway, for they are adept at finding anti-Semitism in places where no one had detected it before. … At the root of it all is an unforgiving rage at the mega-outrage of anti-Semitism—and at the root of that in the modern world is the Holocaust.”[21]

“Sarcasm and Satire Run Riot on the Stage”

Even when not overtly propagandistic like Kosky’s 2017 production of Die Meistersinger or the 2013 Düsseldorf production of Tannhäuser which depicted people dying in gas chambers, productions of Wagner’s operas in the modern era almost invariably seek to satirize the drama in order to subvert the message Wagner attempts to convey. Scruton observes that, notwithstanding the increasingly tiresome preoccupation with dissecting The Ring for anti-Jewish and proto-fascistic themes and images (and counteracting them), Wagner’s celebrated tetralogy is also, on a more basic level, problematic for opera producers because its “world of sacred passions and heroic actions offends against the skeptical and cynical temper of our times. The fault, however, lies not in Wagner’s tetralogy, but in the closed imagination of those who are so often invited to produce it.”1203

The template for modern productions was set with the Bayreuth production of 1976, when Pierre Boulez sanitized the music, and Patrice Chereau satirized the text. Scruton notes that:

Since that ground-breaking venture, The Ring has been regarded as an opportunity to deconstruct not only Wagner but the whole conception of the human condition that glows so warmly in his music. The Ring is deliberately stripped of its legendary atmosphere and primordial setting, and everything is brought down to the quotidian level, jettisoning the mythical aspect of the story, so as to give us only half of what it means. The symbols of cosmic agency—spear, sword, ring—when wielded by scruffy humans on abandoned city lots, appear like toys in the hands of lunatics. The opera-goer will therefore very seldom be granted the full experience of Wagner’s masterpiece.

This certainly describes the Ring I attended in Melbourne in 2016. While the soloists and the orchestra were excellent, the postmodernist, Eurotrash-inspired production detracted from the power of the music and drama. Following established precedent, much of the action was set in a space akin to an industrial wasteland. Siegfried’s heroic forging scene was lampooned by being set it in a tawdry apartment replete with fluorescent lighting, microwave, bar fridge and bunk beds. Fafner (meant to have transformed himself into a dragon) was depicted as a transvestite-like figure smearing make-up on his face and appearing naked on the stage.

Productions like these deliberately sabotage Wagner’s attempt to engage his audiences at the emotional level of religion. They let “sarcasm and satire run riot on the stage, not because they have anything to prove or say in the shadow of this unsurpassably noble music, but because nobility has become intolerable. The producer strives to distract the audience from Wagner’s message, and to mock every heroic gesture, lest the point of the drama should finally come home.”

Brenton Sanderson is the author of Battle Lines: Essays on Western Culture, Jewish Influence and Anti-Semitism, banned by Amazon, but available here and here.

[1] Solomon, “Wagner and Hitler,” op. cit.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Mourby, “Can we forgive him?,” op. cit.

[5] Quoted in Lisa Norris, “Jewish Dwarfs and Teutonic Gods,” H-Net Reviews, September 1997. http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=1318

[6] Quoted in MacDonald, Separation and its Discontents, 56.

[7] Paul Lawrence Rose, Wagner, Race and Revolution (Yale University Press, 1998), 166.

[8] Magee, Wagner and Philosophy, 366.

[9] Quoted in Carr, The Wagner Clan, 182.

[10] Magee, Wagner and Philosophy, 373.

[11] Ibid., 373; 377 & 380.

[12] Gottfried Wagner, The Wagner Legacy: An Autobiography (Sanctuary, 2000), 240.

[13] Solomon, “Wagner and Hitler,” op. cit.

[14] Carol Jean Delmar, “Let the Truth be Heard!,” Ring Festival LA Protest Campaign, June 14, 2010. http://ringfestlaprotest.wordpress.com/2010/06/14/gottfried-wagner-at-the-american-jewish-university-june-6-2010/

[15] Strahan, “Was Wagner Jewish: an old question newly revisited,” op. cit.

[16] Magee, Wagner and Philosophy, 373.

[17] Wagner, “Judaism in Music,” trans. by Bryan Magee, In: Wagner and Philosophy (London: Penguin, 2000), 375.

[18] Ibid., 375-6.

[19] Daniel Barenboim, “Wagner, Israel and the Palestinians,” op. cit.

[20] Magee, Wagner and Philosophy, 374.

[21] Ibid., 373; 380.

Ludwig Geyer

Ludwig Geyer

A 1910 English language edition of Judaism in Music

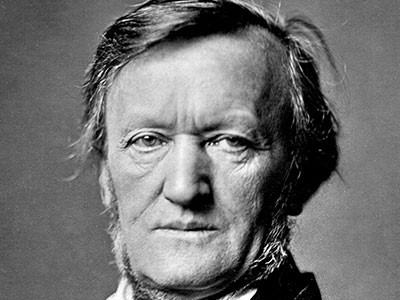

A 1910 English language edition of Judaism in Music Richard Wagner

Richard Wagner

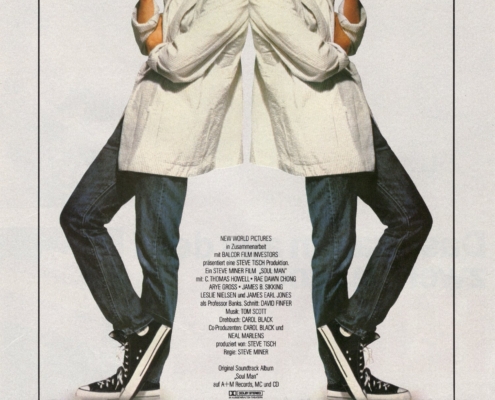

On October 24, 1986 (35 years ago this week), the American comedy

On October 24, 1986 (35 years ago this week), the American comedy

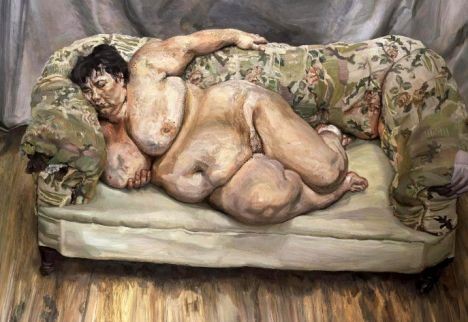

Lucian Freud’s portrait, “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping”

Lucian Freud’s portrait, “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping”