Wagner Reclaimed: A Review of “The Ring of Truth” by Roger Scruton, Part 2

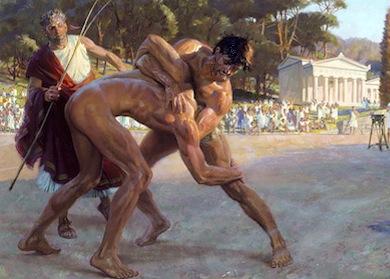

A scene from Neil Armfield’s 2016 Melbourne production of The Ring

“Sarcasm and satire run riot on the stage”

Productions of The Ring in the modern era have invariably sought to satirize the drama to subvert the message Wagner attempts to convey. Scruton observes that, notwithstanding the increasingly tiresome preoccupation with dissecting the tetralogy for anti-Jewish and proto-fascistic themes and images (and counteracting them), The Ring is also, on a more basic level, problematic for opera producers because its “world of sacred passions and heroic actions offends against the sceptical and cynical temper of our times. The fault, however, lies not in Wagner’s tetralogy, but in the closed imagination of those who are so often invited to produce it.”[1]

The template for modern productions was set with the Bayreuth production of 1976, when Pierre Boulez sanitized the music, and Patrice Chereau satirized the text. Scruton notes that:

Since that ground-breaking venture, The Ring has been regarded as an opportunity to deconstruct not only Wagner but the whole conception of the human condition that glows so warmly in his music. The Ring is deliberately stripped of its legendary atmosphere and primordial setting, and everything is brought down to the quotidian level, jettisoning the mythical aspect of the story, so as to give us only half of what it means. The symbols of cosmic agency — spear, sword, ring — when wielded by scruffy humans on abandoned city lots, appear like toys in the hands of lunatics. The opera-goer will therefore very seldom be granted the full experience of Wagner’s masterpiece.[2]

This certainly describes the Ring I attended in Melbourne in 2016. While the soloists and the orchestra were excellent, Neil Armfield’s postmodernist, Eurotrash-inspired production detracted from the power of the music and drama. Following established precedent, Armfield set much of the action in a space akin to an industrial wasteland. He lampooned the heroic forging scene by setting it in a tawdry apartment replete with fluorescent lighting, microwave, bar fridge and bunk beds. Fafner (meant to have transformed himself into a dragon) was depicted as a transvestite-like figure smearing make-up on his face and later appearing naked on the stage (see the lead photograph).

Productions like these deliberately sabotage Wagner’s attempt to engage his audiences at the emotional level of religion. They let “sarcasm and satire run riot on the stage, not because they have anything to prove or say in the shadow of this unsurpassably noble music, but because nobility has become intolerable. The producer strives to distract the audience from Wagner’s message, and to mock every heroic gesture, lest the point of the drama should finally come home.”[3] Read more