William Barret Travis (“Buck”) is the revolutionary idealist of Davis’s book. The Alamoitself was his shining and penultimate moment as its doomed leader who refused to yield his position, thus dying in defense of it. As soon as the fighting began, Travis reportedly rushed out to the North wall and, leaning over the parapet, began blasting away with a double barreled shotgun. Almost instantly, he received a bullet through the forehead in response. He died without dropping his weapon. His final words were “Come on Boys, the Mexicans are upon us, and we’ll give them Hell!”(560).

His five years in Texas locate him at the vanguard of the revolutionary movement, going from lawyer all the way to lieutenant-colonel of a cavalry command that he never got to fully outfit (505). In fact, he had just been commissioned when he was sent to reinforce the Alamo command under J.C. Neill in January of 1836. He arrived with only 30 men and resented the assignment and the difficulty of soliciting volunteers until Neill left on February 11 due to a family illness and put Travis in charge. At that point, “he dropped all pressure to be relieved” (518).

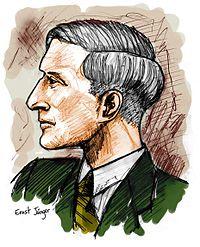

Travis was the youngest of the three men, dying at the age of 26. He also had the best education, furnishing him with the wherewithal to promote the cause of Texas independence through his pen well before he took up the sword. His repeated passionate calls for reinforcements between February 24 and March 5 give us an eloquent and tragic glimpse into the heart of the conflict as well as a striking example of self-sacrificial bravery.

His road to Texasled directly from Claiborne, Alabamawhere he had failed in his initial professional pursuits. After being publicly humiliated by his mentor, James Dellet, in court in early 1831 for debts owed and quite possibly threatened with imprisonment by his creditors, Travis abandoned his wife and two children and headed to Texas, seeking a better fortune and promising to follow through for his family (204–5). He was only twenty years old at the time. Despite the fact that he had passed the bar after only one year of study, at the age of nineteen, had published his own newspaper, The Claiborne Herald, and by all accounts was a very hard worker and an honest man, he was unable to make a living there.Davis suggests that it may’ve just been a combination of a difficult economy and basic maturity issues (206). Alabama, at that time, may also just not have been a large enough stage. A friend commented that “he hungered and thirsted for fame — not the kind of fame which satisfies the ambition of the duelist and desperado, but the exalted fame which crowns the doer of great deeds in a good cause” (205). Read more