Hail the Catholic Church for Forcing Monogamy Upon the Nobility: Chapter 5 of Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition

Prof. Ricardo Duchesne comments on Chapter 5 of Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition.

Since the beginning of his academic career in the early 1980s, Kevin MacDonald has been wondering why only in the West “wealthy, powerful men” have not sought “to control ever larger numbers of women”. Evolutionary biology teaches that male reproductive success benefits greatly from the acquisition of multiple mates. In all societies, except those in which harsh ecological conditions limit the amount of surplus the society can generate, “it is expected that males with wealth and power” will employ their surpluses to “secure as many mates as possible”. This is evolutionary biology 101.

It is also what the historical record shows.

The elite males of all of the traditional civilization around the world, including those of China, India, Muslim societies, the New World civilizations, ancient Egypt, and ancient Israel, often had hundreds and even thousands of concubines.

White elite men were the only ones in history who did not follow this biologically prescribed tendency. We saw in Parts 3 and 4 (of my extended analysis of Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition) MacDonald’s argument that a genetic disposition for monogamy may have evolved among European men back in hunting and gathering times due to harsh environmental conditions in northwest Europe during the last glacial age. In chapter five, “The Church in European History,” which is the subject of this article, MacDonald explains that, while “the Catholic Church cannot be seen as originating monogamy,” this Church was very effective in regulating the sexual behavior of powerful aristocratic men, the ones most inclined to pursue sexual variety.

Many books have been written about how and why Catholicism birthed the modern world. The most popular one is Thomas E. Wood’s How the Catholic Church Built Western Civilization (2012). This book persuasively shows the indispensable role Catholicism played in the creation of universities, the promotion of science and rational law. It asks many interesting questions, such as: “How the Church humanized the West by insisting on the sacredness of all human life?” “How the idea of a rational, orderly universe — fundamental to the Catholic worldview, but absent in non-Christian cultures — made possible the flowering of science in West?”

MacDonald acknowledges the importance of Christian ideas in history. The crucial difference is that he wants to know whether these ideas were actually able “to exert a control function over behavior and evolved predispositions”. What stands out for MacDonald about the Catholic Church was its ability to regulate the sexual behavior of powerful White men in a monogamous direction away from the strong inclination of such men for polygamous relations. Essentially what the Church did was to instill strong religious norms (about mortal sin and punishment in Hell) in the mental processing of the higher brain centers of aristocratic men, damping down the instinctive appetite of the lower parts of the brain for multiple mates.

In this effort, MacDonald pays careful attention to Larry Siedentop’s book, Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism (2014). This book is about the Papal Revolution of the 11th and 12th centuries, which involved the establishment of the supremacy of the papacy over religious affairs, control over the selection of the clergy away from secular aristocrats, the revitalization of Roman law leading to development of Canon law, coupled with the moral restoration and expansion of monasteries manned by a clergy committed to celibacy and the weakening of kinship networks among traditional German aristocratic families. There was a concerted emphasis, this time in the history of the Western family, on marriage based on consent of spouses, prohibition of divorce even if the marriage was infertile, elaboration of rules against consanguineous marriages, and delegitimization of concubinage.

In other words, the Church promoted consensual and egalitarian marriage relations based on the free will of individual men and women. This is what Siedentop means by the Catholic “invention of individualism”. This individualism, according to Siedentop, was rooted both in the Christian notion that humans had individual souls with moral agency and equal value in the eyes of God and in the Greco-Roman idea that one could be a citizen of the polis regardless of tribal identities.

The collapse of Rome, however, and the conquering barbarian Germanic peoples, had resulted in the reinforcement of tribal identities. This is what the Catholic Church set out to undermine. It set out to break down “Germanic tribes organized as kinship groups based on biological relatedness among males,” while simultaneously harnessing their warrior ethos for the spread of Christianity. Codes of honor about one’s kindred and one’s war band, as well as marriage of blood relatives, were still quite strong among Germanic barbarians, notwithstanding their individualist tendencies. MacDonald observes that the prohibition in the sixth century of consanguineous marriages among second cousins was extended by the eleventh century to sixth cousins.

Christian Collectivism Replaces Kin-Based Collectivism

But how can we say that the same medieval age everyone has characterized as “communal” and “collectivist” was the age in which the individualist tendencies of the West were consolidated? MacDonald is quick to point out that the Church itself took on the role of building in the West “a strong sense of group identification and commitment”. The “collectivism of European society in the High Middle Ages was real,” but it was a pan-European ideological-Christian form of collectivism set up against the in-group biological collectivism of smaller kinship groups. It was (if I may express MacDonald’s thesis in unmitigated terms) a collectivism of moral precepts operating at the conscious “higher brain centers located in the cortex” rather than at the instinctive biological levels of the reptilian and mammalian brain. It was a collectivism with its own ambitions for power set up “at the expense” of traditional sources of power — kings and the aristocracy with their persisting kinship networks — with the ability to provide power-seeking Christians incentives to join the expanding and revenue-generating institutional structures of the Church.

It was a collectivism that promoted Western individualism by promoting monogamy, individual choice in marriage outside one’s kinship network, and sexual restraint among powerful aristocratic men. MacDonald goes over other aspects of the Christianized monogamous families of the West, late marriage, relatively high number of unmarried women, celibacy, along with its attendant “low pressure” demographic profile, which lessened consumption of scarce resources and allowed for greater capital accumulation and economic well-being.

But the point I would like to emphasize is the implicit idea in MacDonald that a collective moral identity is consistent with the promotion (or existence) of individualism. Collectivism versus individualism is not the issue. There has never been, and there will never be, a society based on individualism alone. The question is both degree of individualism/collectivism, and the nature of the individualism and collectivism prevailing in a society. As I started arguing in Part 2, weak kinship/tribal ties are not a bad thing, but indeed allow for the rise of broader forms of collective identities, as occurred in ancient Greece when equal citizenship was granted to all native members of the city-state in order to avoid endless tribal conflicts.

Christianity ran against the particular kinship relations and interests of Germanic tribal groupings and aristocratic blood networks, and it did so by cultivating a moral community of believers. Many on the dissident right today blame Christianity for promoting universal values and the equality of human souls across the earth in the eyes of God. MacDonald does not blame Christianity. He does not argue that the Catholic Church created the conditions for the subsequent rise of multicultural collective norms. He is aware, as we will see in future parts, that the same leftists who advocate for the breakdown of biologically-based identities have created powerful moral communities which stand against individual dissent. Instead of calling the West a flat out “individualist” culture, we should rethink very carefully the changing relationships and substantive natures underlying the uniquely Western dialectic between individualism and collectivism.

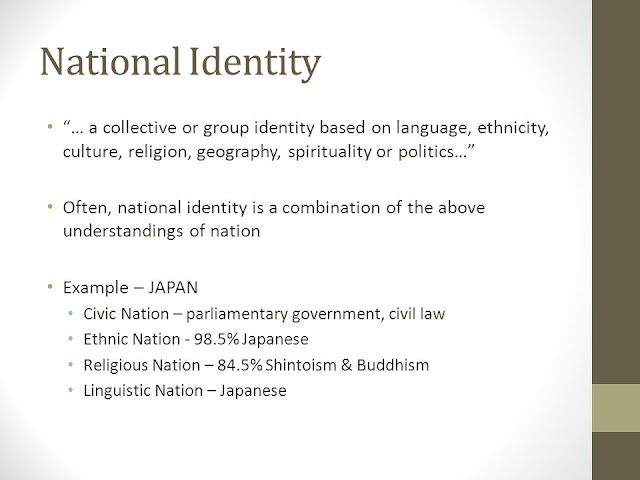

We will see in our examination of chapters 6, 7, 8, and 9 of MacDonald’s Individualism and the Western Tradition that he looks at other intervening stages in the rise of Western individualism, including the way Jewish intellectuals transformed Western individualism into a call for the complete erosion of Western ethnocentric collectivism. One anticipatory question I will allow myself to make now is whether we can look at the rise of Western nationalism in the modern era as a rational strategy by European ethnic groups freed from restrictive tribal identities on the basis of broader territorial ties, historical memories, linguistic similarities, and ethnic lineages.

From their inception, Western national states were heavily ethnic-oriented territories with strict immigration controls up until the 1970s — the most efficient fighting machines and engines of growth created in human history. But increasingly since WWII Whites have been made to believe that the very idea of sovereignty goes against the principle of individual freedom because it “discriminates” against individuals from other nations who have a “human right” to become citizens of Western nations. Europeans need to understand that their individualism can only be fulfilled within a nation state that recognizes the reality of racial and sexual groupings.

There are no chapters in MacDonald’s book on nationalism, and I have never conducted an in depth study of the grand epoch of Western nationalism. But in light of MacDonald’s insights about the peculiar dissolution of Western kinship ties and the rise of individualism, we should start thinking about the dissolution of kinship ties as a process whereby Europeans were trying to generate wider forms of collective identity controllable by the higher brain centers, beyond the lower Darwinian drives that came to prevail in the non-Western world.

This article originally appeared at Eurocanadian.ca.