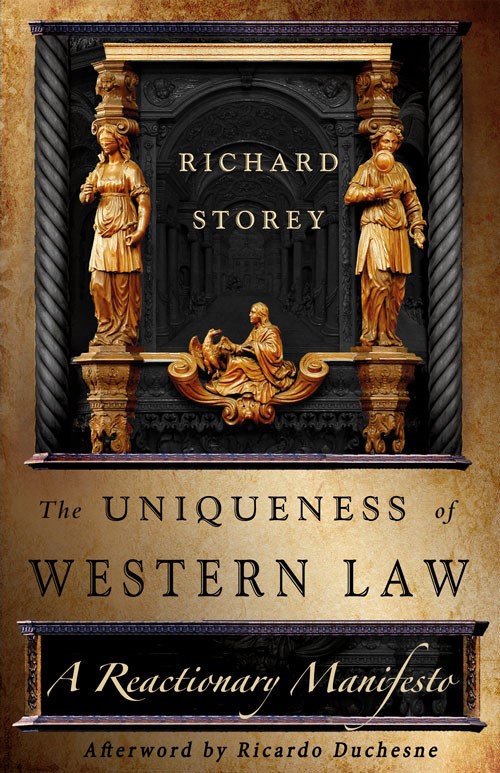

Review: of Richard Storey’s The Uniqueness of Western Law

The Uniqueness of Western Law: A Reactionary Manifesto

Richard Storey

Arktos, 2019

With Washington Summit taking a hiatus and Counter-Currents more or less capitulating in the face of a rapid sequence of Amazon bans, Arktos has emerged as one of the most prolific and stable of the Alt-Right’s publishing brands. Some of this success and stability may be due to the brand’s ability to secure translations of works by familiar names like Alain de Benoist and Julius Evola, as well as bring forward work from new, innovative, and fresh young thinkers like Richard Houck. But I think another, and possibly more important, element contributing to the brand’s ongoing growth and development is consistency — consistency in leadership, editorial standards, production values, and manuscript selection. Over the last couple of years, as a voracious reader of content on numerous topics from multiple sources, I’ve come to appreciate the consistency offered by Arktos in all of these areas. I recently acquired a number of their new titles covering a range of subjects, some of which I expected to agree with wholeheartedly, and others that I thought might challenge me or broaden my understanding in certain areas. Of these, Richard Storey’s self-described “Reactionary Manifesto” fell somewhere in the middle of these expectations. Marketed as “an original interpretation of libertarian theory,” the book was guaranteed to pique my curiosity.

I am not a libertarian, nor have I ever embraced any such political identity or affiliation. My thinking regarding the broader trajectory of libertarian thinking is absolutely in line with that laid out by my TOO/TOQ colleague Brenton Sanderson in his landmark essay “Free to Lose: Jews, Whites & Libertarianism” (TOQ, vol. 11, no., 3; Fall, 2011) For Sanderson, the Jewish intellectual origins of economic libertarianism are explained by the fact that

free markets advance the interests of Jews through imposing an impersonal economic discipline on non-Jews through which their ethnocentricity and anti-Semitic prejudice can be circumvented. … Jews have indeed prospered under the conditions of free market capitalism among often hostile majority European-derived populations. … Jews, even in the freest of markets, are notorious for developing and using ethnic monopolies. … Accordingly, the free-market libertarian agenda, when promoted in the context of a society that is multi-racial, and where some racial groups exceed Whites in the degree of their ethnocentricity, may not promote the group evolutionary interests of Whites in enhancing their access to resources and reproductive success.

Sanderson continues:

It seems evident from the foregoing that the only time that Whites will be acting in their own evolutionary self-interest in embracing the free-market libertarian agenda will be when they either live in a racially homogeneous society where their group interests are not imperiled by the utility-maximizing behavior of individuals; or in a multi-racial society where competing racial groups do not exceed Whites in their ethnocentrism, or exceed Whites in their ethnocentrism but lack the native endowment of intellect to capitalize on this by effectively employing altruistic group strategies in competition with individualistic Whites. … It would seem that libertarian ideas are particularly hazardous to the collective interests of White people because we are naturally attracted to them. As MacDonald notes, our evolutionary history makes us prone to individualism in the first place. You then get a negative feedback loop where libertarian ideology intensifies this innate individualism to encourage ever greater individualism among Whites, and an ever greater aversion to manifestations of White ethnocentrism. Thus, where the spirit of free market libertarian individualism reigns, Whites willingly maximize their individual self-interest at the expense of the group evolutionary interests of the White community — with disastrous long-term consequences.

In terms of analysis, this simply can’t be improved upon. Sanderson’s essay serves as a devastating critique of libertarianism from the standpoint of White ethnic interests, and it has been, and remains, very influential on my thinking about the topic. Thus, even before I opened Richard Storey’s text, I thought that its success would be determined to a large extent by the manner in which it addressed the core issues of ethnic interests and how it grappled with the fact Whites seem uniquely susceptible to individualistic and atomizing ideologies. The fact that Storey is known to frame his thinking in an outwardly Catholic fashion also raised possible doubts as to its potential for wider appeal. Fortunately, this short but remarkably efficient volume rose to the challenge. Read more