William Gayley Simpson on Christianity and the West

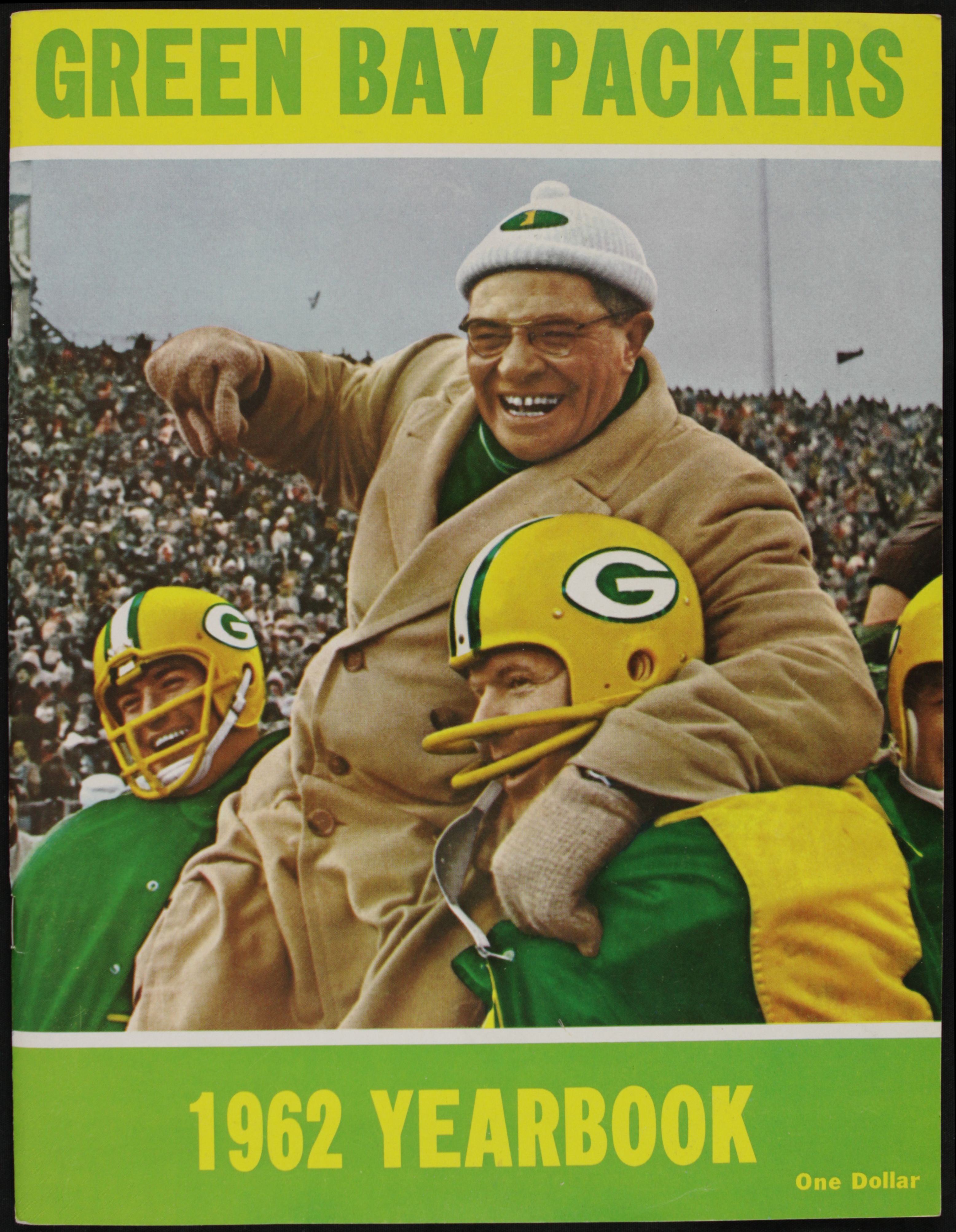

William Gayley Simpson in the early 1940s

The following is adapted from a book I wrote based on interviews with the late white activist William Pierce, The Fame of a Dead Man’s Deeds.

“Someone else you might want to include in this [book] project,” Pierce called out to me as I was leaving his office at the end of one of our evening talks, “is William Gayley Simpson. Do you know about him?”

Very little. All I knew about Simpson was that he had written a book called Which Way Western Man? (free pdf) and that Pierce had published it under his own imprint, National Vanguard Books. I hadn’t read the book.

“Simpson was born in 1892, the same year as my father,” Pierce continued, “so he was a generation ahead of me. In the ’30s he was interacting with the public in a big way, speaking at a lot of universities, mostly about peace issues, how we must never get into another world war and that sort of thing, and at one time he taught Latin, mathematics, and history at a boarding school around where he lived in New York state. Somehow, he had gotten hold of something I had written—this must have been around 1975—and he wrote me about it. At that time, he was over 80-years-old [he died in 1991 at 99].

“We started corresponding. I found Simpson to be a deep, sensitive, and serious man. He invited me to visit him up at his farm. He had built a farmhouse with his own hands, a really nice house, and he had a shop and outbuildings. He did some planting, but mostly he just lived there and thought and wrote and maintained contact [letters in those days] with people from all over the world. I stayed with him a few days and visited him a couple more times after that.

“Simpson told me about a book he was finishing up, which turned out to be Which Way Western Man? I read it and was very impressed and published it. We sold that printing, and then we did two more printings, about seven thousand copies, and sold out on those. Let me get you a copy of Which Way Western Man?”

Pierce stood up from his desk, turned to his left, took a couple of steps, and turned left again through an open door into his library. I followed. It was dark in there—I could barely make out the titles of the books. It was a good-sized room, about fifteen-by-twenty feet. It reminded me of the stacks in a university library, the same kind of metal shelving. Rows of shelves tightly packed from floor to ceiling with books spanned the room’s interior. Pierce had labels taped onto the shelves categorizing his collection, so he knew right where to find the Simpson book. I stood behind him and took in this tall grey-haired man standing in this gloomy library as he turned a few pages of the Simpson book, his eyes just a few inches from the print as he had very poor sight.

Pierce handed me the bulky, dark blue paperback. My hand gave way a bit from the weight of what I later learned was a 758-page volume.

I thanked Pierce for the book and told him I would spend the rest of that evening and the next day looking it over, and that if I could get my thoughts organized I’d talk to him the next evening about what Simpson had written. Read more