Editor’s note: This is the first few paragraphs of an article from Instauration, February, 1979. It is a fascinating portrait of an elite American shortly before the Fall — extreme cowardice on race and Jewish issues combined with a veneer of hyper-masculinity. Even in the 1930s he had withdrawn from the real battles:

At that time, the milieu in which Hemingway moved was the insider’s world of New York, Hollywood, and Paris; and if he had followed the dictum that a writer is supposed to write about what he knows, he would have written about that world. But that would have entailed facing some very unpleasant truths, so he funked it and wrote about Spanish peasants instead.

His real attitudes were expressed behind closed doors:

“I guess I can say spic in my own house,” he said.

“What would Eleanor Roosevelt say to that?” someone shouted.

He made an obscene gesture and smirked. But the joke really was, I suppose, that he would never have dared make it to her in person.

by Cholly Bilderberger

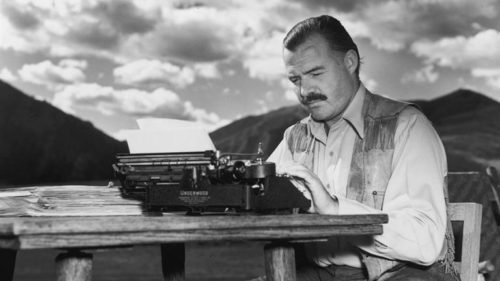

THE MENTION of Ernest Hemingway (pictured) in the December Instaurationtriggered a flood of memories, ranging from amusing to grotesque. He cultivated the rich and powerful assiduously, and our paths crossed often. I ran into him in East Africa, hunting with Winston Guest; bellied up to the bar at the Ritz with Leland Hayward; lunching at 21 with Marlene Dietrich; playing king to the whole world in Havana.

Pertinently enough, he embodied every strain of racism from pitiless clarity to utter confusion. And in him the spectrum was doubly pertinent because he was a national phenomenon, like Byron in his day and Jack Kennedy in his, acting out the fantasies of an entire nation, boozing and womanizing and generally living the American male dreams up to the hilt. His alcoholism, brutality and battiness were ignored and covered over by friends and enemies alike, where those traits in other famous figures were broadcast in detail. He had, again like Jack Kennedy, a strange power over his countrymen — a sort of blackmail in which he said, by implication, “If you dare to tell the truth about me, I’ll tell the truth about you, which is the same truth.” And, yet again like Jack Kennedy, he was the perfect chicken American male, the capon talking in terms of action but perfectly passive (or absent) when it came to going against established interests.

The only people he couldn’t bully were those in positions of power, and to them he was exceedingly deferential. He was always quite polite and pleasant with me, and I enjoyed his company. Oblique and cunning in everything, he nevertheless let you know his exact feelings one way or another.

Read the rest of the article at the National Vanguard site.

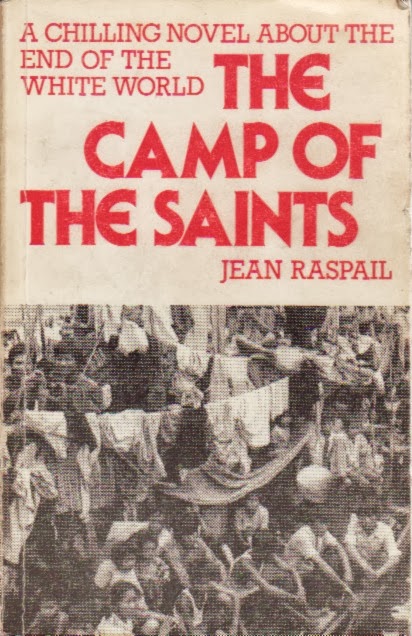

The walls have come tumblin’ down. The Germans and Austrians have thrown their borders wide open. Syrian migrants in their tens of thousands are pouring in. Soon there will be almost a million of them, with an endless queue forming behind them. Word will get out to Africans and Asians: “The West is weak. They have given up. Their resistance is broken. Pick up your bags and let’s join the stream.” Jean Raspail’s Camp of the Saints nightmare has come to pass.

The walls have come tumblin’ down. The Germans and Austrians have thrown their borders wide open. Syrian migrants in their tens of thousands are pouring in. Soon there will be almost a million of them, with an endless queue forming behind them. Word will get out to Africans and Asians: “The West is weak. They have given up. Their resistance is broken. Pick up your bags and let’s join the stream.” Jean Raspail’s Camp of the Saints nightmare has come to pass.