Leonard Bernstein and the Jewish Cultural Ascendancy – PART 2

Bernstein’s Mahler obsession

I have previously examined the tendency of Jewish intellectuals to use their privileged status as the self-appointed gatekeepers of Western culture to advance their group interests through the way they conceptualize the artistic and intellectual achievements of Jews and Europeans. Jews have long used their cultural dominance to construct “Jewish geniuses” to enhance ethnic pride and group cohesion (think Einstein). In this endeavor, Jewish music critics and intellectuals have transformed the image of the Jewish composer Gustav Mahler from that of a relatively minor figure in the history of classical music at mid-twentieth century, into the cultural icon of today. The tendency among Jewish intellectuals has been to overstate and ethnically-particularize Jewish achievement, thereby making it a locus for ethnic pride. Meanwhile, European achievement is downplayed, or where undeniable, universalized and thus neutralized as a potential basis for White pride and group cohesion.

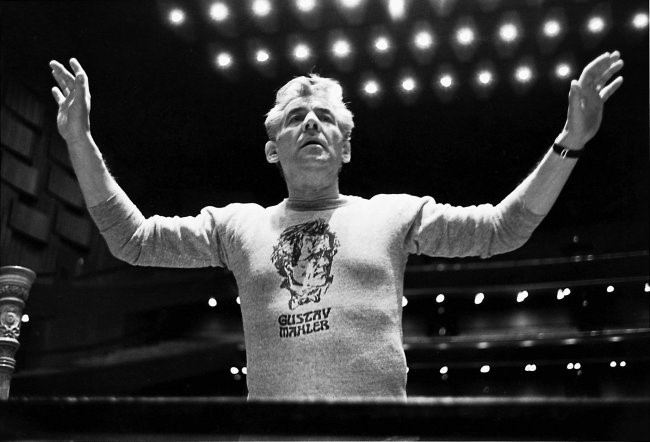

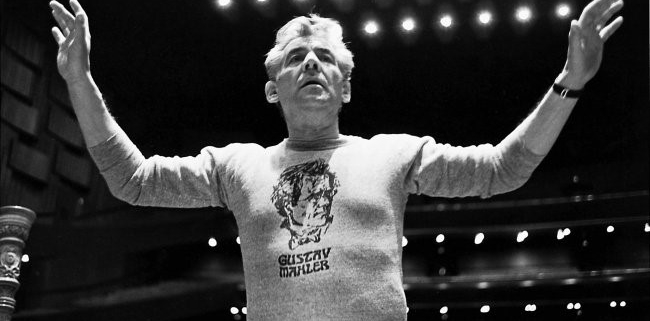

Leonard Bernstein played a leading role in the development of the Mahler cult and the movement of the composer’s music to the center of the classical repertory. The proliferation of performances of Mahler’s music in the United States between 1920 and 1960 can be ascribed to the combined efforts of Bernstein and a coterie of Jewish advocates like Bruno Walter, Arnold Schoenberg, Theodor Adorno, Aaron Copland, and Serge Koussevitzky. Lionizing Mahler as the saintly Jewish victim of European injustice, the Jewish composer Arnold Schoenberg “canonized Mahler as ‘this martyr, this saint’ and in a Prague lecture in March 1912 announced: ‘Rarely has anyone been so badly treated by the world; nobody, perhaps, worse.’”[1] Frankfurt School music theorist Theodor Adorno later took up this theme, affirming that:

Mahler’s tonal chords, plain and unadorned, are the explosive expressions of the pain felt by the individual subject imprisoned in an alienated society. … They are also allegories of the lower depths of the insulted and the socially injured. … Ever since the last of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen Mahler was able to convert his neurosis, or rather the genuine fears of the downtrodden Jew into a vigor of expression whose seriousness surpassed all aesthetic mimesis and all the fictions of the stile rappresentativo.”[2]

Bernstein likewise conceptualized Mahler as a cruelly persecuted and alienated Jew torn apart by dualisms: “composer/conductor, Christian/Jew, sophisticate/naïf, provincial/cosmopolitan — all of which contributed to the musical schizo-dynamics of his texture, and his ambivalent tonal attitudes.”[3] Bernstein advocated for Mahler with missionary zeal, introducing the symphonies to audiences from New York to Vienna. He considered Mahler “the twentieth century’s musical prophet, whose extremes spoke for the times, and thought his symphonies constituted ‘as sacred a bunch of notes as Brahms’s symphonies.’”[4] While all Mahler’s works were available singly on recordings, it was Bernstein who first recorded the complete set of symphonies. Read more

At the heart of the Jewish Question lies an extraordinary level of ethnocentrism. The tremendous capacity of Jews for mutual co-operation and the reinforcement of group identity is one of the behavioral markers that set them apart from most other human populations. This is the case even in comparisons with other populations that, like the Jews, have historically performed roles as ‘middle man minorities.’ Jewish ethnocentrism has thus deservedly been the major focus of attention when scholars or activists have decided to investigate Jewish group behavior. In general these investigations have rested on the obvious expressions of ethnocentrism — clannishness in business, Jewish endogamy, group political strategies, and the manifestation of Jewish group allegiance even in secular cultural contexts (‘Jews without Judaism’).

At the heart of the Jewish Question lies an extraordinary level of ethnocentrism. The tremendous capacity of Jews for mutual co-operation and the reinforcement of group identity is one of the behavioral markers that set them apart from most other human populations. This is the case even in comparisons with other populations that, like the Jews, have historically performed roles as ‘middle man minorities.’ Jewish ethnocentrism has thus deservedly been the major focus of attention when scholars or activists have decided to investigate Jewish group behavior. In general these investigations have rested on the obvious expressions of ethnocentrism — clannishness in business, Jewish endogamy, group political strategies, and the manifestation of Jewish group allegiance even in secular cultural contexts (‘Jews without Judaism’).