“What’s Up, Dr. Mack?” Martians Go Home and the Ordeal of Civility

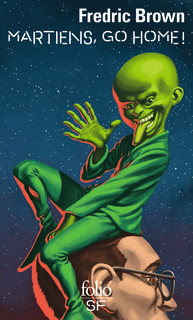

Martians, Go Home

by Fredric Brown

Dutton, 1955; Bantam, 1956

Ballantine Del Rey, 1976

Gateway Essentials, 2011

“But wherever they arrived and however they were received, to say that they caused trouble and confusion is to make the understatement of the century.”

Many a science fiction book or film has a theme, or a debate therein, dealing with the question of whether “aliens” who are advanced enough to master space travel would, ipso facto, “come in peace.”[1] Are they like E.T., or Klaatu, or more like the Martians of the Wars of the Worlds of Wells and Welles?[2]

Many a science fiction book or film has a theme, or a debate therein, dealing with the question of whether “aliens” who are advanced enough to master space travel would, ipso facto, “come in peace.”[1] Are they like E.T., or Klaatu, or more like the Martians of the Wars of the Worlds of Wells and Welles?[2]

But what if they were smart, and indeed not warlike, but instead, just really, really annoying?

Such is the premise of this pulpy little novel by Fredric Brown,[3] whose alien visitors are described by Wikipedia thus:

The story begins on 26 March 1964. Luke Deveraux, the protagonist, is a 37-year-old sci-fi writer who is being divorced by his wife. Deveraux holes himself up in a desert cabin with the intention of writing a new novel (and forgetting the painful failure of his marriage). Drunk, he considers writing a story about Martians, when, all of a sudden, someone knocks on the door. Deveraux opens it to find a little green man, a Martian. The Martian turns out to be very discourteous; he insists on calling Luke ‘Mack,’ and has little in mind other than the desire to insult and humiliate Luke. The Martian, who is intangible, proves to be able to disappear at will and to see through opaque materials. Luke leaves his cabin by car, thinking to himself that the alien was but a drunken hallucination. He realizes that he is wrong when he sees that a billion Martians have come to Earth.

And here’s some more very suggestive details about these alien visitors:

They consider the human race inferior and are both interested and amused by human behaviour. Unlike most fictional Martian invaders, the Martians that Brown writes of don’t intend to invade Earth by violence; instead, they spend their wakeful hours calling everyone ‘Mack’ or ‘Toots’ (or some regional variation thereof), revealing embarrassing secrets, heckling theatre productions, lampooning political speeches, even providing cynical colour commentary to honeymooners’ frustrated attempts at consummating their marriage. This nonstop acerbic criticism stops most human activity and renders many people insane, including Luke, whose stress-induced inability to see the little green maligners divides opinion on whether he should be considered mad or blessed.

If this seems somewhat familiar, you may have had the misfortune of seeing the 1990 film, directed by David Odell and “starring” Randy Quaid and Margaret Colin — a movie so bad it hasn’t seen a Region One DVD release.[4]

But let’s stay with the book. Again, it may seem somewhat familiar, but for another reason: read with a Certain Eye, there are plenty of clues that these Martians are rather Semitic. Read more

In this humorous film about Hitler’s return to modern-day Berlin, Er ist Wieder Da (English title: Look Who’s Back), Germans are caught on camera saying true things about Germany that are not what our elites want to hear. And it happens in the current year. They are so desperate to speak the truth that they are even willing to do so to an actor playing Hitler, Oliver Masucci (Italian and German heritage). This is remarkable, and it speaks to the desperation of German society. There must be such an infinite longing when one cannot dare utter the most commonsensical social observation, without reasonable fear of prosecution or at least censorship; and then to proclaim it for a film crew! It is ironic, and yet also somehow poetic. One cannot whisper the truth, yet one may broadcast it for millions, so long as they are willing to be cast as the fool in a masque of Cultural Marxism; a fool in the Shakespearean sense, which is to say, one who utters unspeakable truisms to an otherwise intolerant authority.

In this humorous film about Hitler’s return to modern-day Berlin, Er ist Wieder Da (English title: Look Who’s Back), Germans are caught on camera saying true things about Germany that are not what our elites want to hear. And it happens in the current year. They are so desperate to speak the truth that they are even willing to do so to an actor playing Hitler, Oliver Masucci (Italian and German heritage). This is remarkable, and it speaks to the desperation of German society. There must be such an infinite longing when one cannot dare utter the most commonsensical social observation, without reasonable fear of prosecution or at least censorship; and then to proclaim it for a film crew! It is ironic, and yet also somehow poetic. One cannot whisper the truth, yet one may broadcast it for millions, so long as they are willing to be cast as the fool in a masque of Cultural Marxism; a fool in the Shakespearean sense, which is to say, one who utters unspeakable truisms to an otherwise intolerant authority.