Review: View from The Right: A Critical Anthology of Contemporary Ideas, Volume I

/33 Comments/in European New Right, Featured Articles/by Andrew Joyce, Ph.D.

View from The Right: A Critical Anthology of Contemporary Ideas, Volume I: Heritage and Foundations

Alain de Benoist (Ed.), trans. Robert Lindgren

Arktos, 2017; orig. published, 1977, with an updated preface (2001) by de Benoist

After 40 years, and following translations into Italian and Portuguese (1981), German (1984), and Romanian (1998), we finally have an English translation of Alain de Benoist’s 650-page magnum opus. Vu de Droite: Anthologie critique des idées contemporaines was first published in 1977 when de Benoist’s GRECE (Research and Study Group for European Civilisation) think-tank was at the height of its influence. It took the French political and intellectual worlds by storm, receiving widespread attention in the mainstream press and winning the Grand Essay Prize from l’Académie française in June 1978.

It is little short of remarkable that we should have to wait four decades for an English translation of a text with such critical acclaim and intellectual pedigree. Credit for bringing about the English translation (published in three handsomely designed volumes and with an updated 2001 Preface) is due to Arktos Media, founded in part in 2010 with the goal of bringing the works of de Benoist to an anglophone readership. A final push to ensure translation of Vu de Droite was initiated in 2016, when seventy-three backers contributed a combined total of around $10,000 via kickstarter.com to bring the project to completion. The dedication and generosity of all involved was not in vain. Although we eagerly await the imminent publication of Volumes Two and Three, the first volume (published in late 2017) is an invaluable work in its own right. Intellectually thorough yet written with admirable economy and agility, View from The Right Volume I: Heritage and Foundations is a useful tool, an invaluable point of reference, and a resounding call to action which has lost none of its relevance or vitality in the decades since its first printing.

The central purpose of View from The Right is to break the taboo on the assertion of right-wing ideas and to present clearly defined intellectual positions (or pathways to positions) on a wide range of subjects as they pertain to right-wing thought. In Volume I, these positions pertain to matters of European racial and cultural heritage, and the broader foundations of contemporary right-wing ideologies. The author describes (ix) his intention to “prepare a portrait of the intellectual and cultural landscape of the moment, to establish the state of affairs, to signal the tendencies, to open the pathways and provide benchmarks to aid (and incite) the task of thinking in a world that is already in the process of considerable change.” For the most part, this effort takes the structural form of powerful and succinct essay summaries of the state of current mainstream scholarship on a number of crucial and fascinating topics. These summaries are then supplemented with commentary from de Benoist and developed still further in his very generous footnotes. Translator Robert Lindgren also deftly assists the reader by occasionally including his own useful commentary on the text, along with a number of very helpful translations and updates of de Benoist’s scholarly citations. Read more

Review of Thomas Goodrich’s “Summer, 1945—Germany, Japan and the Harvest of Hate”

/34 Comments/in Featured Articles/by Thor Magnusson

Sometimes a book comes along that changes the way we think. Sometimes a book comes along that changes the way we act. Sometimes a book comes along that changes the way we think and the way we act. Such a book was Hellstorm—The Death of Nazi Germany, 1944–1947. That masterpiece by Thomas Goodrich changed forever not only how we would view World War Two, but it changed how we would view the world itself. For the first time since it happened, because of one bold and breath-taking book, the scales fell from our eyes and we were finally able to see free and unfettered what the abomination called World War Two was really all about. Swept forever into a dark, dirty corner was the filth and disease of seventy years of Jewish propaganda, seventy years of Jewish lies about the so-called “Good War” and the so-called “Greatest Generation,” seventy years of Jewish mendacity about who was bad and who was good. Suddenly, overnight, replacing those lies was an honest, impartial, unbiased, but driving, relentless, and utterly merciless account of the fate that befell Germany in 1945.

As incredible as Hellstorm was, is, and will always remain, we now know it was only half the story. While the bloody obscenity that was World War Two was being acted out against a largely helpless German population by as evil a cast of creatures as ever haunted any hell anywhere, a similar horror show was taking place on the far side of the globe. And what is revealed in Tom Goodrich’s latest book, Summer, 1945—Germany, Japan and the Harvest of Hate, is a story so savage and sadistic as to numb the senses.

While some of the events described in Summer, 1945 will be familiar to readers of Hellstorm, many will not. Clearly, the author did a vast amount of new research for this new book since much material is previously unknown, especially regarding the contributions of the “Greatest Generation” to its already ghastly list of war crimes against Germany. In fact, what was previously revealed about the Americans in Hellstorm, horrific as it was at the time, was only the faintest foretaste of what was to come in Summer, 1945. For example. . . .

Massive, monstrous, staggering as was the scale of Red Army rape in Germany, it now seems clear that the Americans were not far behind, if behind they were at all. Simply put: No one in control cared. Far from trying to halt the nonstop sexual attacks that their men committed against helpless German females, US officers, like Soviet officers, either ignored them, laughed at them, or actively encouraged them. Upon entering their communities, American officers forced Germans to write the age and sex of all occupants in their homes, then ordered the lists nailed to doors. “The results are not difficult to imagine,” said one horrified priest from a village where women and children were soon staggering to the local hospital after the predictable sexual assaults commenced. Some US generals even blamed the victims themselves for their own gang rape when they dared leave their homes to beg for food. Lt. General Edwin Clarke went further when he announced that the thousands of rape reports in his area were nothing more than a conspiracy by die-hard Nazis to belittle and embarrass his well-behaved and totally innocent troops. Clarke apparently believed that the hundreds of thousands of beaten, bruised and bleeding women and children were all liars with self-inflicted sex wounds. Also, to drive home German defeat, it was noted that GIs were being ordered by their “political officers” to make the gang rapes as public as possible. Although such brutal attacks were already common on streets and sidewalks, in schools and shops, an audience of family members was the preferred crowd for gang rape. Forcing German men to watch was also favored by the Americans, just as it was by their communist comrades. Read more

“Suppressing a Truth of Nature Does Not Make It Go Away”: Guillaume Durocher Interviewed by Hubert Collins

/22 Comments/in Featured Articles, White Racial Consciousness and Advocacy/by Hubert CollinsHubert Collins: You have written a lot—you have nearly 100 posts on Counter Currents alone, plus dozens more spread out across American Renaissance, The Occidental Observer, The Occidental Quarterly, and Radix. In as few words as possible: what motivates it?

Guillaume Durocher: I am thinking out loud, clarifying and systematizing my thoughts, sometimes encapsulating them in a succinct and evocative way. I am also trying to entice others to come down the rabbit hole . . .

Were you a voracious writer before you got involved in the dissident right? What did you write on before your primary focus became race? How did that transition take place?

I wrote about politics and economics. If you are really pursuing the truth and sticking to it, as I like to think I am doing, you’ll fall foul of some dogma sooner or later. In my case, this was the value of the nation. The nation-state is something which the authorities in Europe today openly despise. Raised as a good “end-of-history” democrat, I was appalled that European elites were shifting ever-more power from citizens to unaccountable international bureaucrats and rootless economic forces. In this respect, our leaders are going completely against the republican tradition of the Enlightenment. Rousseau and Jefferson valued sovereignty and autarky. John Jay and Henri Grégoire affirmed the importance of a cohesive national identity to social harmony and civic politics. I was greatly impressed by Raymond Aron, a liberal-conservative Jewish intellectual, who called the homogeneous nation-state “the political masterpiece,” the key to Western nations’ remarkable social organization and dynamism.

When I realized that this identity of Western nations was being almost irreversibly shattered through mass immigration, I went into something of a shock. The rest of the “awakening”—a new understanding of the most taboo topics, namely the Jews, fascism, and race—was very gradual and tortuous. Step by step the assumptions I had been brought up with, which we were all brought up with, were broken down. This was not easy. I try to remember that when I grow impatient with relations and a society still largely in the grip of political correctness.

As anyone familiar with your writing knows, you have spent quite a bit of time in both western Europe, particularly France, and the United States. Which society do you see as more degraded, more unlikely to right its ship? Why?

I’d say we are about equally awful. America tends to obesity, Europe to effeminacy. These are the two poles of postwar democracy, to which each nation gravitates, more or less.

In the short term, a successful national-populist turn, really curbing immigration, seems quite possible on both sides of the Atlantic. As to something more radical . . . we can only speculate. Western Europe is too comfortable. Eastern Europe is too disorganized. Russia may have potential. In America, secession seems like a viable option in the long run. Read more

William Pierce and a Play by George Bernard Shaw

/29 Comments/in Featured Articles, White Racial Consciousness and Advocacy/by Robert S. Griffin, Ph.D.

William Pierce

The only real tragedy in life is being used by personally minded men for purposes you recognize to be base.

All civilization is founded on [man’s] cowardice, on his abject tameness, which he calls his respectability.

Men will never really overcome fear until they imagine they are fighting to further a universal purpose—fighting for an idea.

George Bernard Shaw

In the early part of this century, I published a portrait, as I called it, of the white activist William Pierce, who died shortly thereafter, called The Fame of a Dead Man’s Deeds. I called the book a portrait rather than a biography because it was basically my sense of Pierce after spending a month living in close contact with him on his remote compound in West Virginia.

Pierce was the most remarkable human being I have ever been around. He was incredibly intelligent and enormously committed to doing something of lasting worth with his life. In stark contrast to how his adversaries depicted him, he was a decent and kind person, a gentleman, a gentle man. I’ve never seen anyone work that hard—ten, twelve, fourteen hour days, seven days a week. One of Pierce’s prime traits, he took ideas very seriously and lived in accordance with the ones that gave him direction in his life’s project of living an honorable and meaningful existence in the time he had allotted to him on earth (it turned out to be 68 years). One major source of perspective and guidance for Pierce was a stage play, Man and Superman, by George Bernard Shaw. The following is an excerpt from the Fame book about that play’s impact on him.

“As an undergraduate in college [at Rice University in Texas],” Pierce told me, “I had a nagging worry about whether I was doing the right thing with my life. Did I really want to be a physicist, the route I was taking at that time? What standards best assess the paths in life I might take? I had an awareness of my mortality from a very early age, and it seemed to me that I shouldn’t waste my life doing things that weren’t truly important. I didn’t want to be on my deathbed thinking, ‘I’ve blown it; I had one life to live, and I didn’t do what I should have done.’

“When I got to Oregon State as a professor of physics [in 1962], I started to do more general reading—before, with all my science courses, I hadn’t had the time—and gradually things started to take shape about what was important in my life. It was a process of taking the insights and teachings from what I was reading and refining them and learning how to exemplify them.

“One of the things that helped me find direction was a play I first came upon at Caltech [where he had gotten his doctorate] back in 1955 or so—Man and Superman. Act three of the play was the one that really struck me. It expressed the idea that a man shouldn’t hold himself back. He should completely use himself up in service to the Life Force. I bought a set of phonograph records that just had that act. As I remember, it had Charles Laughton, Charles Boyer, Agnes Moorehead, and Cedric Hardwicke—it was well done.

“Don Juan’s expositions were what resonated with me. I listened to that set of records over and over and let it really sink in. The idea of an evolutionary universe hit me as being true, with the evolution toward higher and higher states of self-consciousness, and the philosopher’s brain being the tool for the cosmos coming to know itself. Over time, I elaborated upon this idea—I came to call it Cosmotheism—and discussed it in a series of talks I gave in the 1970s.” Read more

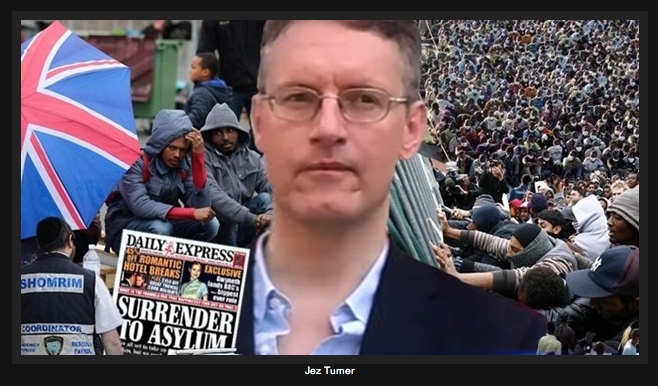

“Let My People Stay!” The Jailing of London Forum’s Jez Turner

/43 Comments/in Featured Articles, White Racial Consciousness and Advocacy/by

https://www.bitchute.com/video/R6isFzdNJfo8/

Despite the Crown Prosecution Service’s hesitation to put on trial an intellectual, a truth teller, an upstanding citizen, a patriot, and a man who was prepared to lay down his life for his country in war, they were forced by the extra-judicial demands of the Sanhedrin to do so, and this modern Cheka managed to squeeze out of a reluctant court one year’s imprisonment for “incitement to racial hatred,” a Talmudic verdict forced on the British legal system by that very group who is insistent in Britain that they are not a race but a religion.

Despite the Crown Prosecution Service’s hesitation to put on trial an intellectual, a truth teller, an upstanding citizen, a patriot, and a man who was prepared to lay down his life for his country in war, they were forced by the extra-judicial demands of the Sanhedrin to do so, and this modern Cheka managed to squeeze out of a reluctant court one year’s imprisonment for “incitement to racial hatred,” a Talmudic verdict forced on the British legal system by that very group who is insistent in Britain that they are not a race but a religion.https://www.bitchute.com/video/8QhnfkhCa6uo/

What the West Can Learn from the Buddha and Gandhi

/34 Comments/in Featured Articles/by Guillaume Durocher

Writing during the Second World War, Julius Evola observed: “If one day normal conditions were to return, few civilizations would seem as odd as the present one, in which every form of power and dominion over material things is sought, while mastery over one’s own mind, one’s own emotions and psychic life in general is entirely overlooked.”[1] He who wishes to change the world should first of all start with himself: the insight may seem trivial, but we should bear this in mind in all our pursuits.

Evola made this comment in a ground-breaking work on Buddhism, a spiritual path which he believed had much to teach the West. Actually, there is nothing particularly Eastern about the ideal of self-mastery through a disciplined daily spiritual life. There are clear Western analogues in the Greco-Roman philosophical tradition to many Buddhist insights and practices. From Socrates onwards, the ancient philosophical tradition recognized that the first good was that of our own soul, the state of one’s psyche. The Stoics in particular seem similar to the Buddhists, emphasizing our relative impotence over the world’s constant flux, and that the only thing we should rightly seek to control is our own mind.

The French academic Pierre Hadot has emphasized that ancient Greco-Roman philosophy, unlike its modern Western counterpart, was not a purely intellectual or theoretical enterprise. Rather, the ancient philosophers practiced spiritual exercises and a particular way of life in order to train and transform their minds, and to prepare themselves for the acquisition of wisdom. Typical practices included physical austerities, a frugal lifestyle, contempt for material possessions, living in a community of like-minded philosophers, disinterested dialogue, mathematical abstraction, prolonged meditation, and the contemplation of death. Many of the basic insights and practices of late Hellenistic philosophy would be codified by and live on in Christianity.

Today however, Buddhism has an enormous advantage over Greco-Roman philosophy: it is a living spiritual tradition, rather than reduced to dusty books, however valuable they might be. There’s no comparing fossil bones with a live-and-kicking dinosaur. The teaching and law given by the mysterious Prince Siddhārtha Gautama, the Buddha, some 2,500 years ago has stood the test of time. Buddhism, unlike Greco-Roman philosophy, was institutionalized in a large monastic community, the sangha, which explicitly and systematically enjoined a particular spiritual way of life. Through the practice of contemplating the workings of the mind and the world in a spirit of detachment, the Buddha claimed we could learn to see existence as it truly is.

Ethics and politics, if they are to be lasting and healthy, must be grounded in an accurate conception of the way things are, and in particular of human nature, which is grounded in biology. Any political order, such as communism or multiculturalism, which is grounded in a false conception of human nature, is bound to collapse. The current liberal-egalitarian order is based on false assumptions about the genetic component of human biological nature, radically underestimating the importance of inborn qualities and of the differences in inborn qualities both between individuals and between populations. I do not need to tell the readers of The Occidental Observer that this leads to tremendous negative social consequences, particularly for the European peoples. In the long run, these false ideas make liberal-egalitarianism unsustainable. Read more