In Clown They Trust: The Farce and Foulness of Clown World

The Jewish genius Hannah Arendt was wrong about “the banality of evil.” Evil is often entertaining and interesting, combining both farce and foulness. That’s why the term “Clown World” was invented. It’s used by thought-criminals like Vox Day to describe governments, corporations, and churches in the modern West. We’re ruled by Jew-designed ideologies – black supremacism, transgenderism, feminism – whose elite enforcers are as evil and arrogant as they are incompetent and inept. In other words, they’re evil clowns. Among much else, the evil elite clowns are determined to tear down the borders that maintain society and civilization. For example, transgenderism is about elite clowns tearing down the border between male and female so that perverted men can indulge their fetishes by pretending to be women.

Elite clowns in America: Joe Biden is a puppet of Jewish power

For an excellent example of that broken border and a trans-clown in action, take a Scottish criminal who has just hit the headlines in Britain. Dressed as a woman, a “transitioning” pedophile called Andrew Miller, also known as Amy George, went cruising for prey and tricked a pre-teen schoolgirl into his car. He then drove her to his home, confined her to his bedroom, and sexually assaulted her over 27 hours. In between sexual assaults, he refreshed his libido by watching porn and fetish videos on TV. He rejected the girl’s repeated pleas for freedom and told her that she was now his “new family.”

Silicone villainy

Then, understandably tired out by his transgender activism, he fell asleep. The girl was able to escape the bedroom, find a phone, and ring the police. When the police arrived, they found Miller still asleep and wearing “a bra, silicone breasts, female pants and tights.” In a subsequent interview, Miller told the police that he had been trying to “help” the girl. She looked “freezing,” he said, and tricking her into his car had been the “motherly thing” to do. And he had “put her in bed with me to warm up.” The transphobic police didn’t believe him. He was charged with abduction, sexual assault, and “intentionally causing a child under the age of 13 to look at a sexual image.” And with possession of “242 indecent images of children.” He later pleaded guilty to all charges.

Trans-clown Amy George, a.k.a Andrew Miller

That’s Clown World at its funniest and foulest. But it’s possible that stories like that help the transgender cause rather than harm it. I’ve argued in the article “Dykes Are Dull!” that leftists’ adolescent desire for novelty and entertainment is a big part of their support for translunacy. Unlike boring lesbians, “transwomen” are very entertaining. Like Jonathan Yaniv in Canada, Andrew Miller in Scotland is one of the many trans-clowns who have invaded female territory to indulge their sexual perversions. However, the left view such trans-clowns not with disgust, but as a misunderstood and marginalized minority. And because the evil of transgenderism is entertaining, it’s even more attractive to the left. Applying their core principle of “Preach Equality, Practice Hierarchy,” leftists have placed trans-clowns far above lesbians, let alone the straight women who don’t want trans-clowns in female toilets and dressing-rooms, or competing in female sports.

Importing non-White psychopaths

So don’t assume Miller’s farcical crimes will harm the transgender cause. They may do the exact opposite. Leftists are drawn to evil and want to be entertained. Trans-clowns like Miller satisfy both leftist needs. But I’m not a leftist and when I read about his crimes, I was reminded of another Scottish schoolchild who suffered even worse things because of Clown World’s war on borders. The schoolgirl abducted by Andrew Miller pleaded with him for freedom. He must have seen her fear and distress, but he rejected her pleas. Luckily for her, she got out alive. The Scottish schoolboy Kriss Donald wasn’t so lucky after he was abducted by a gang of vicious Pakistani criminals in 2004. The Pakistanis were in Scotland because elite clowns had opened Britain’s borders to violent and corrupt non-Whites. Kriss Donald too pleaded for freedom, but his abductors were unmoved by his fear and distress. They had abducted him at random because he was White and they murdered him in horrific fashion because he was White. Kriss Donald was doused in gasoline, set alight, then stabbed repeatedly and left to die in agony.

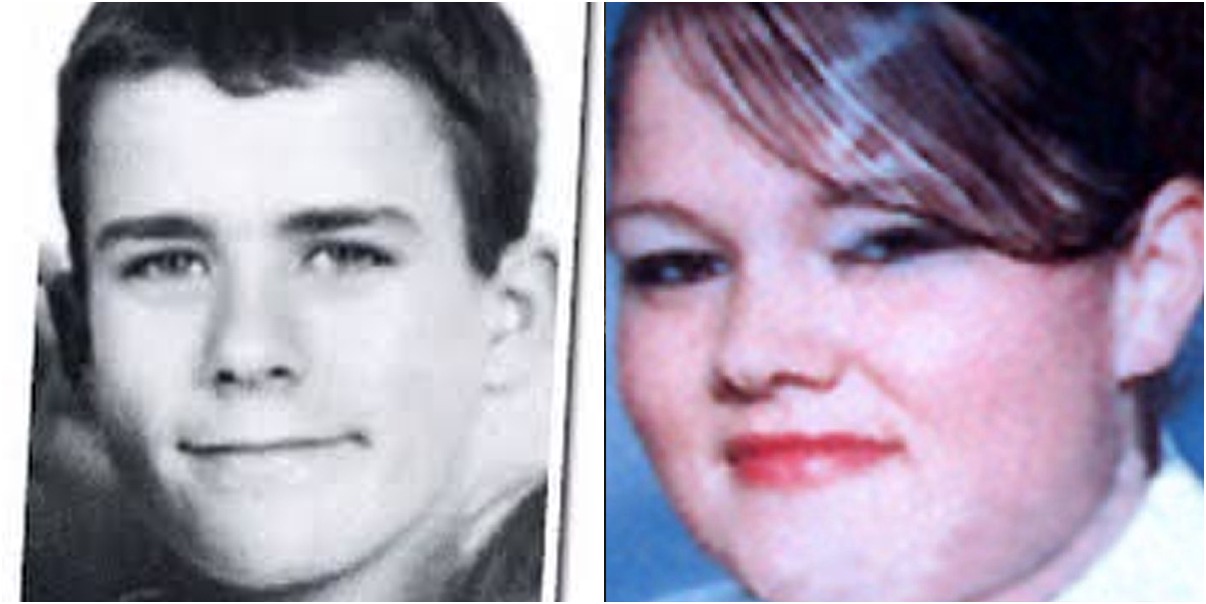

Kriss Donald and Mary-Ann Leneghan, two young white victims of Clown World

Kriss Donald and Mary-Ann Leneghan, two young white victims of Clown World

The following year, in 2005, a White schoolgirl called Mary-Ann Leneghan was abducted by a Black gang in England, raped and tortured over hours, then stabbed to death as she too pleaded for mercy. Again, the Blacks were here because elite clowns had opened Britain’s borders to non-Whites. But while White schoolchildren are victims of the war being waged on the West by elite clowns, non-White schoolchildren are trainee footsoldiers in that war. Take the great English county of Yorkshire. It’s still famous for the toughness and enterprise of its White natives, the grandeur of its landscapes, and the strength of its devotion to cricket. Now it’s also infamous for its Pakistani rape-gangs. But not as infamous as it should be. Clown World tried but failed to hide the horrors being inflicted on working-class White girls in the small Yorkshire town of Rotherham. Even worse has gone on in bigger places. We got a glimpse of that when more Pakistani rape-gangs preying on White girls were exposed in the Yorkshire town of Huddersfield in 2018, as I described in “Huddersfield Horrorshow.” In April 2023 Huddersfield is back in the news for its vibrancy:

Two stupid, violent and impulsive Blacks who have enriched Yorkshire courtesy of Clown World

Two teenage cousins who stabbed a 15-year-old boy to death as he walked home from school in West Yorkshire have been jailed for life. Jovani Harriott, 17, and Jakele Pusey, 15, murdered Khayri McLean after ambushing him outside North Huddersfield Trust School last year.

The judge, Mrs Justice Farbey, said the cousins had seen Khayri as their “enemy” and may have killed him in “revenge” for sharing a video online about a broken window at Harriott’s mother’s house. Det Supt Marc Bowes, of West Yorkshire Police, said it “will be hard for many of us to comprehend” how a “low-level dispute” ended with two boys “stabbing a fellow student to death at the end of an otherwise ordinary school day”.

Prosecutor Jonathan Sandiford KC said Khayri was killed in a “well-planned” attack on 21 September. Dressed in black and wearing balaclavas, the defendants waited in an alleyway before ambushing him as he walked along Woodhouse Hill with friends after school. Pusey shouted Khayri’s name while “jumping into the air” and stabbing him in the heart with a 30cm blade, the court heard. His cousin, who was 16 at the time of the attack, then knifed Khayri in the leg.

Khayri was pulled to his feet by his friends and tried to run away but collapsed. He died later in hospital. Harriott, who was 16 at the time of the attack, was convicted of murder in March while Pusey pleaded guilty to murder at an earlier hearing.

Mr Sandiford told the court Pusey had admitted murdering Khayri in a recording covertly obtained while he was in detention. During the conversation, the boy said he felt “no remorse” and claimed to have “slept better” since the killing, the prosecutor said. His lawyer Richard Wright KC, in mitigation, said Pusey – who was in a gang called the Fartown Boys – had been exploited and “drawn into a life” in which “he felt he belonged, was protected and accepted”.

The court heard the boy had told probation officers he was shot by masked men in a “gang incident” when he was 12 and had dealt drugs since he was 13. Det Supt Bowes, who led the police investigation into Khayri’s murder, said the “appalling attack” had “rightly shocked people across the country” and “highlighted the dreadful consequences of knife crime and the culture of carrying such weapons”. (Khayri Mclean: Huddersfield teens jailed for life over schoolboy stabbing, BBC News, 18th April 2023)

Note that Detective Superintendant Marc Bowes was playing a role often assigned to police officers in Clown World. They express incredulity about the way stupid, violent, and impulsive non-Whites can’t and won’t conform to White standards of behavior. But they don’t put it like that, of course. Bowes said that it “will be hard for many of us to comprehend” the savagery of the two Black boys in question. He was wrong. It isn’t hard to understand at all. Blacks evolved in the distinct environments of sub-Saharan Africa, where natural selection favored aggression and impulsivity over intelligence and self-control. Clown World favors the same anti-civic behavior in its Black footsoldiers. In America, the Black minority are the chief practitioners and victims of gun-crime. In Britain, the Black minority are the chief practitioners and victims of knife-crime.

Jew-puppet Joe Biden

The weapons differ, but the genetically mediated Black behavior is the same. So is the way that Clown World blames Black pathologies on White racism in both countries. For example, the evil and stupid movement known as Black Lives Matter (BLM) was invented by clowns in America and taken up eagerly by clowns in Britain. As Steve Sailer has tirelessly and irrefutably demonstrated, BLM has been responsible for a big increase in the number of Blacks murdered and maimed by other Blacks. And also in Blacks killed by dangerous Black driving. The evil elite clowns don’t care, because those elite clowns don’t genuinely care about the welfare of Blacks and other non-Whites. No, they genuinely care about only one thing: destroying the White West.

That’s why they wage war on borders, allowing trans-perverts to invade female territory and non-White savages to invade White territory. When the Jew-puppet Joe Biden said that “white supremacy” is “the most dangerous terrorist threat” to America, he meant that Whites are the biggest obstacle to the triumph of Clown World. But only if Whites wake up to how the elite clowns hate them and want to destroy their lives, their future, and their civilization. Fortunately, the arrogance and incompetence of Clown World will ensure that Whites wake up by the million. As the trillion-dollar farce of Afghanistan proved, clowns can easily start wars but they can’t ever win them.