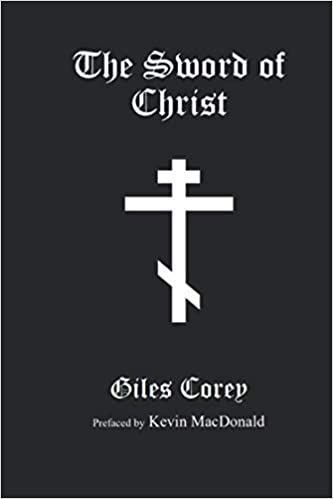

Kevin MacDonald’s Preface to Giles Corey’s The Sword of Christ

Note: Giles Corey’s new book, The Sword of Christ, may be purchased here. Get it before it’s banned!

Giles Corey has written a book that should be read by all Christians as well as White advocates of all theoretical perspectives, including especially those who are seeking a spiritual foundation that is deeply embedded in the history and culture of Europeans. This is excellent scholarship combined with a very fluid writing style. He has thought deeply about all the issues confronting the peoples and cultures of the West.

Corey is well aware that contemporary Christianity has been massively corrupted. Mainline Protestant and Catholic Churches have become little more than appendages for the various social justice movements of the left, avidly promoting the colonization of the West by other races and cultures, even as religious fervor and attendance dwindle and Christianity itself becomes ever more irrelevant to the national dialogue. On the other hand, Evangelicals, a group that remains vigorously Christian, have been massively duped by the theology of Christian Zionism, their main focus being to promote Israel.

Until the twentieth century, Christianity served the West well. One need only think of the long history of Christians battling to prevent Muslims from establishing a caliphate throughout the West—Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours, the Spanish Reconquista, the defeat of the Turks at the gates of Vienna. The era of Western expansion was accomplished by Christian explorers and colonists. Until quite recently, the flourishing of science, technology, and art occurred entirely within a Christian context.

Much of my scholarly interest has been to attempt to understand the people and culture of the West, resulting in my book Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition: Evolutionary Origins, History, and Prospects for the Future. As I argue there, individualism lends itself to moral and ethical universalism which led to the religiously based eradication of slavery long before the rise of an elite hostile to Christianity itself. And White intellectuals in the nineteenth century attempting to understand their own moral universalism often attributed it to their racial origins.

Such individualism was not disastrously self-destructive. As Corey notes, “Christian universalism historically posed little to no danger to White survival because it was preached by Whites living in a world ruled by Whites; it was only in the multicultural Egalitarian Regime inseminated in the mid-twentieth century that Christian sacrifice was transformed into a call for racial suicide.” The individualist, Christian West was thus highly adaptive—until the rise of a hostile, Jewish-dominated elite bent on corrupting adaptive forms of Christian individualism in favor of a completely deracinated individualism, now accompanied by powerful religious, media, and academic voices preaching White guilt, often from a Christian perspective.

Instead, Corey advocates a revitalization of Medieval Germanic Christianity based on, in the words of Samuel Francis, “social hierarchy, loyalty to tribe and place (blood and soil), world-acceptance rather than world-rejection, and an ethic that values heroism and military sacrifice.” This medieval Christianity preserved the aristocratic, fundamentally Indo-European culture of the Germanic tribes. This was an adaptive Christianity, a Christianity that was compatible with Western expansion, to the point that by the end of the nineteenth century, the West dominated the planet. Christianity per se is certainly not the problem.

The decline of adaptive Christianity coincides with the post-Enlightenment rise of the Jews throughout the West as an anti-Christian elite, and Corey has a great deal of very interesting material on traditional Christian views of Judaism. Traditional Christian theology viewed the Church as having superseded the Old Testament and that, by rejecting the Church, the Jews had not only rejected God, they were responsible for murdering Christ. My view, developed in Chapter 3 of Separation and Its Discontents: Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism is that traditional Christian theology was fundamentally anti-Jewish and was developed as a weapon which was used to lessen Jewish economic and political power in the Roman Empire. Here Corey describes the writings of the fourth-century figure, St. John Chrysostom, who has a chapel dedicated to him inside St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome as well as a statue outside the building. His writings on Jews are nothing less than scathing and reflect long-term tensions between Jews and Greeks in Antioch. And Chrysostom was far from alone in his hatred. For example, St. Gregory of Nyssa, also writing in the fourth century: “ [Jews are] murderers of the Lord, assassins of the prophets, rebels against God, God haters, . . . advocates of the devil, race of vipers, slanderers, calumniators, dark-minded people, leaven of the Pharisees, sanhedrin of demons, sinners, wicked men, stoners, and haters of righteousness.” The traditional Church was certainly far from friendly toward Jews.

And although Protestantism was generally far more amenable to Jewish interests even before its current malaise, there certainly are exceptions. Here Corey emphasizes Martin Luther’s writings on Jews. Luther emphasizes Jewish hatred toward Christianity and their sense of superiority vis-à-vis Christians, seeing the latter as “not human; in fact, we hardly deserve to be considered poor worms by them.” But he is also concerned about Jewish economic exploitation and domination of Germans via usury—certainly the biggest complaint about Jews in traditional Europe. And he is repulsed by Talmudic ethics which promote very different moral codes for Jews and non-Jews.

However, much has changed since the origins of Christianity. In the contemporary United States, Christian Zionism has had a very large influence on Evangelical Protestantism whose theology departs radically from traditional Christianity, particularly with respect to the Jews. Corey has an excellent section on how Jews helped shape this new theology; it should be required reading for Christian Zionists because it would open their eyes to the sordid history of the movement. The result of such thinking is that Zionism has often become a vehicle of moral idealism in the minds of a great many gentiles, from Lloyd George to the present, who believe that the restoration of Israel is far more important than the fate of their own people.

Jews have not stood by idly on this but have actively supported the Christian Zionism movement. I noted in a 2010 article on the delusional Pastor John Hagee:

Beginning in 1978, the Likud Party in Israel has taken the lead in organizing this force for Israel, and they have been joined by the neocons. For example, in 2002 the Israeli embassy organized a prayer breakfast with the major Christian Zionists. The main organizations are the Unity Coalition for Israel which is run by Esther Levens and Christians United for Israel, run by David Brog. The Unity Coalition for Israel consists of ~200 Christian and Jewish organizations and has strong connections to neocon think tanks such as the Center for Security Policy, headed by Frank Gaffney, pro-Israel activist organizations the Zionist Organization of America, the Likud Party and the Israeli government. This organization claims to provide material for 1,700 religious radio stations, 245 Christian TV stations, and 120 Christian newspapers.[1]

Corey notes that Hagee’s organization, A Night to Honor Israel, has donated over $100 million to right-wing causes in Israel over the years. He has been well rewarded financially for his efforts and is the recipient of numerous awards from Zionist organizations.

Christian Zionism is a fitting reminder of how humans, unlike animals, can be motivated by ideas, including ideas that are completely unrelated to believers’ real interests. These ideas may be disseminated by people who are only doing so for selfish reasons, such as the dishonorable Cyrus Scofield, whose annotated Bible has become central to Christian Zionism. Maladaptive ideas may also be disseminated by people who are utterly opposed to the legitimate interests of believers or even hate Christianity and the West in general. Here Corey discusses the role of Felix Untermeyer, a wealthy Jew, in promoting Scofield and his Bible. It was a religious ideology “with a new worship icon—the modern state of Israel,” and Corey does an excellent job showing how Christian Zionism is a radical departure from traditional Christian theology. I found the following passage quite stunning:

The heresy of Christian Zionism, using an arbitrary and self-contradictory literalist and futurist hermeneutic, contends that the Jews remain God’s chosen people, separate from and superior to the Church; indeed, they believe that earthly Jewish Israel will replace the Church, and that as such, “Christians, and indeed whole nations, will be blessed through their association with, and support of, Israel.”

Although Christian Zionism is far less influential than the Israel Lobby in furthering Jewish interests in the United States, it has certainly had some influence and creates a ready-made cheering section for wars in the Middle East on behalf of Israel. After all, other attitudes typical of Christian Zionists, such as opposition to abortion or pornography, have had much less traction with the current left-oriented establishment despite their powerful commitment to the state of Israel.

Religious thinking is by its nature unbounded—it is infinitely malleable. It is a dangerous sword that can be used to further legitimate interests of believers, or it can become a lethal weapon whereby believers adopt attitudes that are obviously maladaptive. One need only think of religiously based suicide cults, such as People’s Temple (Jonestown), Solar Temple and Heaven’s Gate. Mainstream Christianity from traditional Catholicism to mainstream Protestantism was fundamentally adaptive in terms of creating a healthy family life. It was compatible with a culture characterized by extraordinary scientific and technological creativity and standards of living that have been much envied by the rest of the world.

Corey has great material on Jewish perceptions of Christianity in the Talmud and on negative Jewish influences on culture in the present West, including pornography and the sexual revolution generally. As is so often the case with Jewish activism, the pornography movement has been motivated not solely by money but by hatred toward Christian morality and Christian family functioning. The results have been devastating: huge increases since the 1960s—the breakthrough decade of Jewish power—in all the markers of family dysfunction and poor child outcomes: lower marriage rates, higher births out of wedlock, higher rates of teenage pregnancy, precocious sexuality, high divorce rates, and unstable pair bonds. In other words, the Western family pattern of monogamous nuclear families based on strong husband-wife pair bonds has been under attack from Jewish dominated movements, the most noteworthy of which was psychoanalysis promising an idyllic future if only people would jettison traditional Christian constraints on sexuality. These negative trends in family functioning have been most pronounced among the lower social classes and thus have much less effect on high-IQ middle- and upper-income groups, including Jews as a relatively high-IQ group. The disaster in family patterns has fallen far more severely on the White working class.

Corey’s has an extended treatment of the corrosive effects of pornography, now extended to child pornography and legalized pedophilia as the “final frontier” in the sexual revolution. As in other areas, this starts out by advocating language that makes the activity more or less acceptable depending on the interests of advocates. In the case of pedophilia, the first step is to label them “minor attracted persons,” whereas in the area of free speech, we find labels like “hate speech”—even for speech that is reasonable and fact-based. If issues related to free speech are any guide, there will soon be articles in law journals arguing that pedophilia is normal and should not be punished, and eventually courts will begin to adopt this logic in particular cases. Already Supreme Court justices like Elena Kagan have signaled a willingness to curtail speech on diversity issues,[2] and this would be joined by the other liberals, which would mean that curtailing free speech on race is at most one Supreme Court appointment away. And when that happens, it won’t be long before it is embraced by conservatives. As Corey notes in the case of pedophilia, “We are presumably one Supreme Court ruling away from the National Review cocktail ‘conservative’ crowd celebrating pederasty as the next great achievement of individual liberty.”

Given the exhaustive summary of the negative effects of pornography—including neurological impairments related to impulsivity and lessened interest in familial relationships of love and nurturance—it is horrifying indeed that “sixty percent of boys and thirty percent of girls were exposed to pornography in early adolescence, including ‘bondage, rape, and child pornography’, and another which concludes that children under ten years old now account for over twenty percent of online pornographic consumption.” This definitely was not happening when I was growing up in the 1950s, prior to the deluge. I agree with Corey’s conclusion, “We have conclusively established that Jewish leadership and participation was instrumental in and a necessary condition of the pornographic war that has struck at the most sacred foundation of the West, the family.” As Freud famously said, “we are bringing them the plague.”

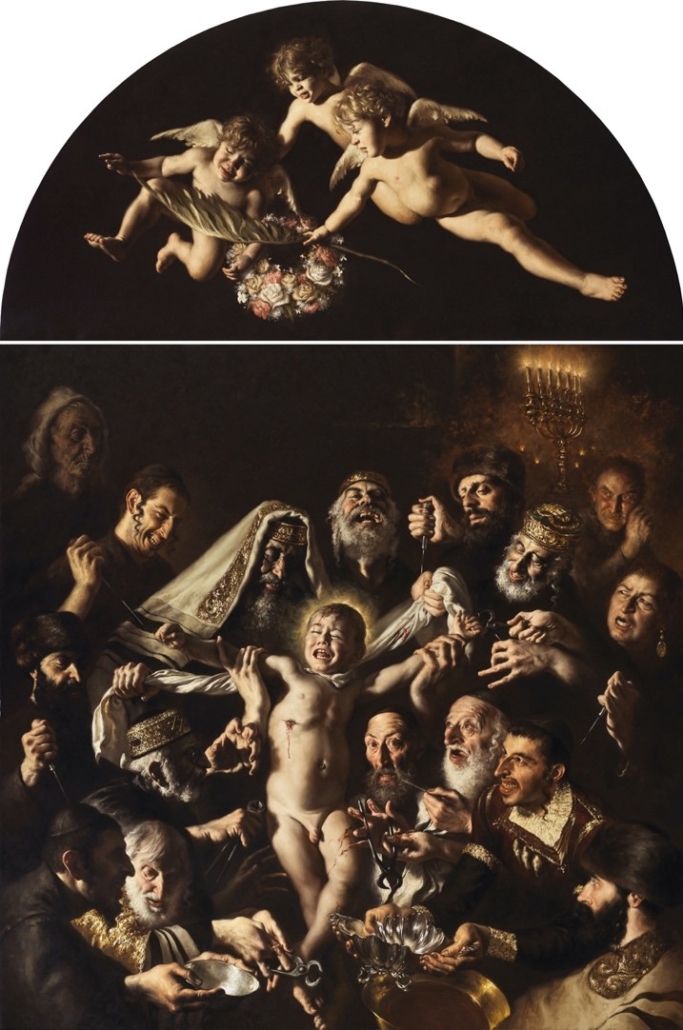

Corey has an excellent and exhaustive section on Jewish ritual murder—an absolutely convincing presentation on a topic that, like so much of Jewish history, is a minefield for serious scholars. As he notes, “There are … hundreds of accusations and cases of Jewish ritual murder, each just as sadistically depraved as the last, involving barrels of nails, crucifixion, decapitation, spit-roasting, stoning, and a litany of other barbaric evils; we could fill entire volumes with the accounts of each of these innocent lives so cruelly taken from this world.”

This is a topic that I have never written about, although I was somewhat familiar with Blood Passover, Ariel Toaff’s book on the topic. As to be expected, Toaff’s book was condemned by the activist Jewish community and he was pressured into publishing an apology, promising to prevent distribution of his book, etc. However, we should not be surprised to find that such practices occurred. Ritual murder is an extreme manifestation of normative Jewish hostility toward the surrounding society which is an important facet of the entire subject. The eighteenth-century English historian Edward Gibbon was struck by the fanatical hatred of Jews in the ancient world:

From the reign of Nero to that of Antoninus Pius, the Jews discovered a fierce impatience of the dominion of Rome, which repeatedly broke out in the most furious massacres and insurrections. Humanity is shocked at the recital of the horrid cruelties which they committed in the cities of Egypt, of Cyprus, and of Cyrene, where they dwelt in treacherous friendship with the unsuspecting natives; and we are tempted to applaud the severe retaliation which was exercised by the arms of the legions against a race of fanatics, whose dire and credulous superstition seemed to render them the implacable enemies not only of the Roman government, but of human kind.[3]

The nineteenth-century Spanish historian José Amador de los Rios wrote of the Spanish Jews who assisted the Muslim conquest of Spain that “without any love for the soil where they lived, without any of those affections that ennoble a people, and finally without sentiments of generosity, they aspired only to feed their avarice and to accomplish the ruin of the Goths; taking the opportunity to manifest their rancor, and boasting of the hatreds that they had hoarded up so many centuries.”[4]

As I noted in an article titled “Stalin’s Willing Executioners: Jews as a Hostile Elite in the Soviet Union,” “Hatred toward the peoples and cultures of non-Jews and the image of enslaved ancestors as victims of anti-Semitism have been the Jewish norm throughout history—much commented on, from Tacitus (“they regard the rest of mankind with all the hatred of enemies”[5]) to the present.”[6] Toaff brings out the revenge motive: “In their collective mentality, the Passover Seder had long since transformed itself into a celebration in which the wish for the forthcoming redemption of the people of Israel moved from aspiration to revenge, and then to cursing their Christian persecutors, the current heirs to the wicked Pharaoh of Egypt.”

Hatred and revenge were clearly on display in the early decades of the Soviet Union, a period in which around 20 million people were murdered. From “Stalin’s Willing Executioners,” a review of Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century:

There can be little doubt that Lenin’s contempt for “the thick-skulled, boorish, inert, and bearishly savage Russian or Ukrainian peasant” was shared by the vast majority of shtetl Jews prior to the Revolution and after it. Those Jews who defiled the holy places of traditional Russian culture and published anti-Christian periodicals doubtless reveled in their tasks for entirely Jewish reasons, and, as Gorky worried, their activities not unreasonably stoked the anti-Semitism of the period. Given the anti-Christian attitudes of traditional shtetl Jews, it is very difficult to believe that the Jews engaged in campaigns against Christianity did not have a sense of revenge against the old culture that they held in such contempt. …

Slezkine seems comfortable with revenge as a Jewish motive, but he does not consider traditional Jewish culture itself to be a contributor to Jewish attitudes toward traditional Russia, even though he notes that a very traditional part of Jewish culture was to despise the Russians and their culture. (Even the Jewish literati despised all of traditional Russian culture, apart from Pushkin and a few literary icons.) Indeed, one wonders what would motivate the Jewish commissars to revenge apart from motives related to their Jewish identity. …

Slezkine’s argument that Jews were critically involved in destroying traditional Russian institutions, liquidating Russian nationalists, murdering the tsar and his family, dispossessing and murdering the kulaks, and destroying the Orthodox Church has been made by many other writers over the years. …

The situation prompts reflection on what might have happened in the United States had American Communists and their sympathizers assumed power. The “red diaper babies” came from Jewish families which “around the breakfast table, day after day, in Scarsdale, Newton, Great Neck, and Beverly Hills have discussed what an awful, corrupt, immoral, undemocratic, racist society the United States is.”[7] … It is easy to imagine which sectors of American society would have been deemed overly backward and religious and therefore worthy of mass murder by the American counterparts of the Jewish elite in the Soviet Union—the ones who journeyed to Ellis Island instead of Moscow. The descendants of these overly backward and religious people now loom large among the “red state” voters who have been so important in recent national elections. Jewish animosity toward the Christian culture that is so deeply ingrained in much of America is legendary. As Joel Kotkin points out, “for generations, [American] Jews have viewed religious conservatives with a combination of fear and disdain.” And as Elliott Abrams notes, the American Jewish community “clings to what is at bottom a dark vision of America, as a land permeated with anti-Semitism and always on the verge of anti-Semitic outbursts.”

As the quote from neocon Elliott Abrams—and much else—indicate, this fear and loathing continues into the present. Consistent with what we know of the psychology of ethnocentrism, a fundamental motivation of Jewish intellectuals and activists involved in social criticism has simply been hatred of the non-Jewish power structure perceived as anti-Jewish and deeply immoral—Susan Sontag’s “the white race is the cancer of human history,” which was published in Partisan Review, a prominent literary journal associated with the New York Intellectuals (a Jewish intellectual movement), is emblematic.

As I write this in the summer of 2020, we are experiencing what feels like the end game in the Jewish conquest of White America. Because Jews have become a hostile elite with a powerful position in the media and educational system, Jewish attitudes in the 1950s that the U.S. is an “awful, corrupt, immoral, undemocratic, racist society” are now entirely mainstream and the cancel culture that we see now is indeed directed most of all toward White red state voters, particularly in the South. Cancel culture started with toppling Confederate monuments, but of course it didn’t stop there, so now statues of the Founding Fathers are being destroyed and there are demands that statues dedicated to Christian religious figures be removed. Jews in particular have demanded the removal of a statue of King Louis IX of France because of his attempt to curb Jewish moneylending in the interests of his people and for burning 12000 copies of the Talmud.

The Cathedral of Notre Dame burning, April 15, 2019. Much of the cathedral was built during the reign of St. Louis.

This hatred won’t end if and when Whites become a minority. Jews were responsible for the 1965 immigration law that opened up the United States to immigration from all over the world, and they have energetically worked to make alliances with these immigrant groups who are encouraged to hate White America and often adopt anti-White rhetoric almost as soon as they arrive because they can see the political advantages of doing so.

This won’t end well. As I concluded in my recent book, Individualism and the Western Liberal Tradition:

I agree with Enoch Powell: “as I look ahead, I am filled with foreboding; like the Roman, I seem to see ‘the River Tiber foaming with much blood.’”[8] All the utopias dreamed up by the Left inevitably lead to bloodshed—because they conflict with human nature. The classical Marxist Utopian vision of a classless society in the USSR self-destructed, but only after murdering millions of its own people. Now the multicultural utopian version that has become dominant throughout the West is showing signs of producing intense opposition and irreconcilable polarization.

Given the very large Jewish involvement in these projects consequent to the Jewish rise to elite status throughout the West, the big picture is that the thrust of Jewish power has been to create societies envisioned as being good for Jews, inevitably advertised in idealistic, morally uplifting, humanitarian terms [to appeal to the evolutionary psychology of individualism where social ties are based on belong to moral communities rather than communities based on kinship ties]. Historically, such projects have typically not ended well and have resulted in massive social upheavals. It would thus not be surprising if current social divisions result in a movement characterized by anti-Jewish overtones. …

All of the measures of White representation in the forces of social control will continue to decline in the coming years given the continued deterioration of the demographic situation. At this point, even stopping immigration completely and deporting illegals would not be enough to preserve a White America long term.

The left and its big business allies have created a monster. Whites have to realize that if they do nothing, they will be increasingly victimized and vilified in the coming decades as the monster continues to gain power. Better that any blood be shed sooner rather than later.

What happened in the early decades of the Soviet Union is a chilling reminder of what can happen when an alien hostile elite seizes control of a country.

I agree entirely with Corey’s conclusions and recommendations for a revival centered around the adaptive aspects of Christianity—the aspects that produced Western expansion, innovation, discovery, individual freedom, economic prosperity, and strong family bonds. A Christianity that is adaptive in the evolutionary sense of survival and reproduction and fundamentally cognizant of the mistakes of the past.

We must not tolerate subversion. Liberalism must go; we cannot afford to repeat the mistakes of the Enlightenment. We cannot afford to countenance any further anti-American, anti-family, anti-White speech, and this should be reflected in a new Constitution. Just as conservatism was not enough, the United States Constitution was not enough, with gaps that left it gaping wide for judicial “interpretation.” For another thing, we must circle the wagons and inculcate the männerbund, restraining our individualism at least for the time being. For another, we must return to our Lord and Savior. A nation without faith can have no guiding light, no purpose, no drive, no Mission. Izaak Walton, writing of his friend John Donne’s last days, described the body “which was once a temple of the Holy Ghost and is now become a small quantity of Christian dust.” His last line: “But I shall see it reanimated.”

Kevin MacDonald, August 9, 2020

[1] Kevin MacDonald, “Christian Zionism,” The Occidental Observer (March 12, 2010).

https://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/2010/03/12/kevin-macdonald-christian-zionism/

[2] Kevin MacDonald, “Elena Kagan: Jewish Ethnic Networking Eases the Path of a Liberal/Leftist to the Supreme Court, The Occidental Observer (May 20, 2009).

https://www.theoccidentalobserver.net/2009/05/20/elena-kagan/

[3] Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol.1, ed. J. B. Bury (London: Methuen, 1909), 78.

[4] Quoted in W. T. Walsh, Isabella of Spain: The Last Crusader (New York: Robert M. McBride, 1930), 196.

[5] Tacitus, The History 5, 4, 659.

[6] Kevin MacDonald, “Stalin’s Willing Executioners: Jews as a Hostile Elite in the USSR.” Review of Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. The Occidental Quarterly, 5(3), 65–100, 93–94.

[7] This quote comes from Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique, Chapter 3.

[8] “Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ Speech,” The Telegraph (November 6, 2007).

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/comment/3643823/Enoch-Powells-Rivers-of-Blood-speech.html