Introduction

Weak-willed Anglo-Protestants in Canada meekly acquiesced in official recognition by their federal government of Jewish political theology in the form of the Holocaust mythos. This is hardly surprising in light of their failure a few years earlier to resist repeal of a milquetoast Criminal Code provision prohibiting only the most egregiously vulgar displays of blasphemous libel.[i] Having already surrendered the historical theological hegemony of Protestant Christianity in English Canada, Anglo-Protestants hardly seem likely to resurrect the ethnoreligious mythos which inspired the Old English church of their medieval ancestors. Such Protestant pusillanimity stands in stark contrast to the aggressively ethnocentric political theology of organized Jewry, not just in Canada, but across the entire Anglosphere. If contemporary WASPs had any self-respect, they would rush to remedy the absence of a spiritually compelling, bioculturally adaptive, Anglican/Anglo-Protestant ethnotheology.

Optimism on that score is probably unwarranted, however. Few WASPs know or care much about their ethnoreligious origins. Even most members of the Anglican church believe that it came into being with the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation. It was then that Henry VIII formally broke with Rome for reasons of state. Before then, the ecclesia Anglicana had been absorbed within the institutional framework of a papal monarchy asserting universal jurisdiction. Allied with a French-speaking, Anglo-Norman ruling class, the Roman Catholic papacy had no reason to preserve the explicitly ethnoreligious character of the Old English Church. Nor did the break with the papacy precipitate an Anglo-Saxon ethnoreligious revival; beyond replacing the Pope with the King as the formal head of the Church of England, the new state religion retained its traditional commitment to the catholicity of the Three Creeds enshrined in the Thirty-Nine Articles. But, whatever the intentions of those who set the Protestant Reformation in motion, over the next few centuries, the combined impact of English and American Protestantism deformed beyond recognition the very idea of Christian nationhood.

As James Kurth writes, the doctrinal base of the Anglo-Protestant Reformation “protested against the idea that the believer achieves salvation through a hierarchy or a community, or even the two in combination.” Of course, the reformed Church of England “accepted hierarchy and community for certain purposes, such as church governance and collective undertakings [but] they rejected them for the most important of purposes, reaching the state of salvation.” Protestant reformers held that “the believer receives salvation through an act of grace by God.” It is divine grace that “produces in its recipient the faith in God and salvation that converts him into a believer.” Hence, “reformers placed great emphasis on the Word, as revealed in the written words of the Bible.” They denied that only a priestly hierarchy could deliver the right interpretation of the Bible to individual believers. Indeed, authoritative hierarchies were more likely to impede the work of divine grace upon individual believers seeking a direct relationship with God through personal study of the Holy Scriptures.[ii]

The initial “Protestant rejection of hierarchy and community in regard to salvation spread to their rejection in regard to other domains of life as well.” From the beginning, “some Protestant churches rejected hierarchy and community in regard to church governance and local undertakings.” Nowhere were such anti-institutional tendencies more pronounced than “in the new United States, where the conjunction of the open frontier and the disestablishment of churches in the several states enabled the flourishing of new unstructured and unconstrained denominations.”[iii]

Over the past five-hundred years, the Protestant faith gradually lost its spiritual intensity, a process which began when salvation by grace was replaced by the “half-way covenant” in which grace could be evidenced by works.[iv] Then, even “the idea of the necessity of grace began to fade.” Once “work in the world was no longer seen as a sign of grace but as a good in itself,” good works offered the promise of personal salvation. The transformation of religious experience into a personal relationship to God was an early expression of Anglo-Protestant individualism. In our own time, the transformation of religion into a personal and private matter has culminated in the recognition of universal human rights as the sacred birthright of every individual. According to Kurth, “this means that human rights are applicable to any individual, anywhere in the world.”

Thus, “the ultima ratio of the secularization of the Protestant religion” has become an “expressive individualism” in which the imperial self is free to express his/her/its “contempt for and protest against all hierarchies, communities, traditions, and customs.” In other words, Kurth writes, “the long declension of the Protestant Reformation has reached its end point in the Protestant Deformation,” producing a religion without God, “a reformation against all forms.”[v]

Expressive individualism in America was inspired by the romantic-humanistic ethic prevalent among Progressive reformers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most of whom were middle-class WASPs. But it was the massive wave of immigration from southern and central Europe which provided the raw material enabling the WASP clerisy to manufacture the cosmopolitan spirit characteristic of urban America during the Progressive Era.

Confronted with the tightly-packed masses of immigrants in New York and Chicago, middle-class reformers learned “to interpret Protestant Christianity in a very peculiar, almost secular way.” In adapting “the tenets of egalitarian humanism to their polyglot, culturally-charged context,” the reform movement established “settlement houses” to assist alien newcomers in adjusting to life in America. Anglo-Protestant reformers such as Jane Addams and John Dewey led the campaign to recognize and accept immigrant cultures “as a ‘gift’ to the American amalgam.” They implored the American nation “to shed its Anglo-Saxon ethnic core and develop a culture of cosmopolitan humanism, a harbinger of impending global solidarity.”[vi] Other Anglo-Protestant reformers such as William James urged their fellow WASPs to embrace a pragmatic approach to religious experience, choosing whichever “type of religion is going to work better in the long run.” It did not matter much whether God was dead, so long as “we form at any rate an ethical republic here below.”[vii]

An American century later, Kurth notes that, by then, almost every nation with a Protestant religious tradition has “by now adopted some version of the human rights ideology.”[viii] One might add that the many manifestations of Anglo-Protestant humanism in various corners of the Anglosphere do not always maintain logical consistency. In Canada, for example, the offence of blasphemous libel was removed from the Criminal Code in the name of the universal human right to free expression just four years before the decision to criminalize anyone who condones, denies, or downplays the Jewish Holocaust.[ix] No-one should be surprised to learn that organized Jewry overwhelmingly approved both pieces of legislation. After all, Jews are now held up as exemplary victims of those who would deny or abuse human rights. At the same time, however, neither measure appears to have encountered any serious opposition from Anglo-Canadian Protestants, even though both (especially taken together) would have been interpreted as deformations of Christian nationhood by earlier generations of Protestants in English Canada. Almost everywhere in the Anglosphere, such Protestant deformations of traditional Christian mores have been consecrated, sooner or later, by globalist churches with the full support of the Holocaust industry.

All too often, either the Church of England or its Anglican successors in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States have been in the vanguard of that moral declension. We need to understand the historical roots of such dysgenic institutional behavior. Unfortunately, even the recent rise to prominence of “Christian nationalism” in the USA is unlikely to reverse the Protestant Deformation.

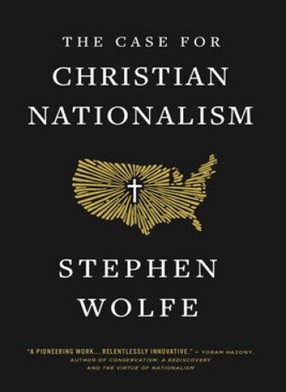

Christian Nationalism, American-Style

A recent book by Stephen Wolfe making The Case for Christian Nationalism has much to recommend it.[x] As an unapologetic paleoconservative, the author blames the postwar Global American Empire (GAE) for undermining Christian nationhood at home in the USA, perhaps terminally. “In the New America,” he observes, “the ground of patriotic sentiment is away from the Old America. Thus, civic holidays, national heroes, memorials, and patriotic events are all colored according to the grand narrative of progress.” Even mainstream conservatives are committed to the progressivist narrative of US history, so much so that they are the staunchest supporters of the military which, they believe, fights to defend “the American way of life.” But, despite his experience as a West Point graduate serving in the U.S. army in the world-wide “fight for democracy,” Wolfe now advises young men not to get “blown up in the name of liberal imperialism; shed blood to open up markets for Netflix and Pornhub; [or to] make the world safe for dudes in dresses.”[xi]

He holds the GAE responsible for undermining the moral and cultural foundations of Christian nationhood. Not only has the imperial regime imposed homosexual marriage upon all the states by judicial fiat, it also steeps young minds in critical race theory and gender-bending ideology. Meanwhile, the floodgates have been opened to a tidal wave of non-Western immigration, further eroding the once-dominant Anglo-Protestant character of American national identity. Nevertheless, in opposition to the relentless onslaught of nihilistic disenchantment, Wolfe holds out the hope that Christian nationalism could inspire a “true revolt against the modern world.” He believes in the possibility of “the pursuit of higher life—both the life to come and a life on earth that images that life to come.” Indeed, he insists that Christians can still regard the world as their “inheritance in Christ.” With undisguised passion, Wolfe presents Christian nationalism as “a collective will for Christian dominion in the world.”[xii]

But what prevents Christians from exercising the biblical mandate to exercise dominion over this world? The problem, as Wolfe sees it, is essentially psychological. American Christians “have been so conditioned to affirm what we feel to be good that the feeling determines for us what is true. Conversely, we deny any thought that we feel is bad.” Some beliefs, notably Christian nationalism, are psychologically more difficult for churchgoers to entertain than others.[xiii]

Most Anglo-American Protestants, for example, have long been conditioned, by both church and state, to regard religion as a private and personal matter. Wolfe’s vision of Christian nationalism cuts across the grain of those habits of religious privatism. For example, Wolfe calls upon civil government to protect and preserve the exclusively Christian identity of the nation by penalizing “open blasphemy and irreverence in the interest of public peace and Christian peoplehood.” Few mainstream Christians will be “comfortable” with his argument that “Sabbath laws are just, because they remove distractions for holy worship.”[xiv]

Similarly, Wolfe’s case for upholding the legitimacy of traditional gender hierarchies has already attracted accusations of “misogyny.” On this issue, however, Wolfe pulls no punches. He declares that Americans “live under a gynocracy—a rule of women.” He concedes that this “may not be apparent on the surface, since men still run many things. But the governing virtues of America are feminine vices, associated with certain feminine virtues, such as empathy, fairness, and equality.” Any such defense of “toxic masculinity” runs contrary to feminist norms eagerly enforced by the established secularist regime. But Wolfe remains unrepentant, declaring flatly that the “rise of Christian nationalism necessitates the fall of gynocracy.”[xv]

Inevitably, therefore, the very idea of Christian nationalism represents an existential threat to the Woke liberal regime. Wolfe bluntly characterizes “the secularist ruling class” as “the enemies of the church and, as such, enemies of the human race.”[xvi] At the same time, he recognizes that to resist the moral and political consensus enforced by a godless regime, Christians must summon the hitherto absent strength of will necessary to affirm what is true even when it causes them enormous psychological discomfort.

To his credit, Wolfe admits that many Christian leaders deliberately undermine political action in opposition to the secularist regime. Instead, they “advance a sort of Stockholm syndrome theology” which excludes “Christians from public institutions” but requires them “to affirm the language of universal dignity, tolerance, human rights, anti-nationalism, anti-nativism, multiculturalism, social justice, and equality.” Wolfe deplores the fact that any Christian who “deviates from these dogmas” faces exclusion from the ranks of respectable churchgoers.[xvii] What, then, is to be done? Wolfe turns to Christian political theory in search of an answer. Unfortunately, the result, even for many of his Christian readers, leaves much to be desired.

Nationalism and Christianity

Wolfe’s book has attracted wide interest in a multitude of online reviews and podcast discussions. Understood as a political program, Wolfe’s conception of Christian nationalism is often pronounced DOA, dead on arrival. For example, Neema Parvini, author of The Populist Delusion, dismisses Christian Nationalism as a “political fantasy.”[xviii] In fairness, however, Wolfe himself readily agrees that, on the national level at least, the idea has little chance of success. He does not present the book as a viable “action plan.”[xix] Instead, he sets out the principles that should guide any Christian nation. Wolfe’s preferred model of Christian nationalism is grounded in a Reformed Presbyterian version of two-kingdoms theology which distinguishes between God’s redemptive work of salvation and his providential governance of earthly affairs.

Accordingly, he defines Christian nationalism in the following manner:

Christian nationalism is a totality of national action, consisting of civil laws and social customs, conducted by a Christian nation as a Christian nation, in order to procure for itself both earthly and heavenly good in Christ.[xx]

In other words, “Christian nationalism is nationalism modified by Christianity” which is to say that “the Gospel does not supersede, abrogate, eliminate, or fundamentally alter generic nationalism, it assumes and completes it.” Apart from Christianity, therefore:

Nationalism refers to a totality of national action, consisting of civil laws and social customs, conducted by a nation as a nation, in order to procure for itself both earthly and heavenly good. [xxi]

According to Wolfe, “the specific difference between generic nationalism and Christian nationalism is that, for the latter, Christ is essential to obtaining the complete good.” The ordering of people to heavenly life would have been “a natural end for even the generic nation” but for the fall. “Had Adam not fallen, the nations of his progeny would have ordered themselves to heavenly life.” Following the advent of Christ as the Redeemer, “the Gospel is now the sole means to heavenly life.” If nations are to achieve their “complete good,” even “earthly goods ought to be ordered to Christ.” Without Christ, pagan and secularist nations may be “true nations but they are incomplete nations. Only the Christian nation is a complete nation.”[xxii]

Wolfe situates all nations and nationalisms, Christian or otherwise, within a Reformed Presbyterian vision of salvation history. Wolfe describes his argument as a “Christian political theory” rather than a “political theology” grounded in his own biblical exegesis. His understanding of Scripture relies instead upon the work of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Reformed theologians. That Reformed tradition developed within a metanarrative framework established by Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD). Augustine and the later Reformed tradition posit a fundamental metaphysical distinction between the City of Man and the City of God. Both interpret Scripture through the lens of a Hellenistic hermeneutic envisioning the creation ex nihilo and future destruction of the earthly world as the appearance and foreordained disappearance of corruptible material existence following the Day of Judgement.[xxiii]

Augustine’s neo-Platonic cosmology presupposed the absolute dependence of both mankind and the material world itself upon an omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent God. Following in Augustine’s footsteps, Wolfe believes that modern Americans seduced by the delights of mortal life in Mammon have wandered far from heavenly goods, thereby losing sight of “the invisible things of God.” Given the inherent difficulty mortal beings experience in apprehending such invisible divine “objects,” Wolfe, too, recognizes our spiritual debt to the revealed Word of God. He holds fast to the Augustinian doctrine that, guided by the light of the Gospel, Christian nations should view their entire existence as a journey towards the unchangeable heavenly life, and their affections should be entirely fixed upon that.[xxiv]

It follows that “politics” in every Christian nation must be understood as “the art of establishing and cultivating necessary conditions for social life for the good of man.” The point of a Christian political life comes from God; it must aim to create civil governments capable of shoring up the social order “for man’s complete good.” In other words, the difference between generic nationalism and Christian nationalism is that the latter “expresses a Christian nation’s will for heavenly good in Christ and that all lesser goods are oriented to the higher good.” [xxv]

Presented in such universalistic, all-encompassing terms, Wolfe’s “Christian political theory” transforms “politics” into “public administration.” Civil government, he says, must aim to identify the most effective earthly means within any given society to realize a heavenly destiny common to faithful believers in every Christian nation.

Action versus Behavior in Political Theory

In this context, the “totality of national action” is better understood as a socially ordered system of behavior premised upon the existence of one common interest, i.e., the interest of every Christian society not just in its own earthly survival and collective vitality but also in the heavenly salvation of every believer. Public administration, as distinguished from politics, may become detached from natural persons and lodged instead in a social life-process which requires that human behavior conform to the developmental needs (both spiritual and material) of society. Wolfe seems unaware that “politics,” strictly speaking, originally required the institutionalization of a realm of freedom in which civic action became possible.

The distinction between “action” and “behavior” was central to Hannah Arendt’s political theory. In her view, “action” was the means by which the individual could distinguish himself from others in the public realm. For a citizen to leave the private sphere of the household “to devote one’s life to the affairs of the city demanded courage” because entry into the “political realm had first to be ready to risk his life, and too great a love for life obstructed freedom, was a sure sign of slavishness.” With the administrative victory of society over the public realm, the possibility of individual action gives way to the statistical regularities of human behavior, while the equality of men possessed of the acknowledged right to reveal themselves in their own distinctive public persona becomes degraded into conformism to the assumed common interest of society as a whole.[xxvi]

Not only does Wolfe’s “Christian political theory” fail to offer an “action plan,” it fails even to recognize the existential need for a public realm. It is only in such a res publica that individuals, families, tribes, and nations are able to distinguish themselves, one from the other, through exemplary modes of civic action. Such recognition of the distinctive character of political life has been the exception rather than the rule in human affairs. Arendt may have been concerned primarily with the phenomenology of politics, but she well understood that the unique character of a civic mode of action was first discovered in ancient Greece, most famously in the Athenian polis.[xxvii] To fully understand the early experience of politics and its decline in the totally administered societies characteristic of the modern transnational corporate welfare state, it is necessary to study, not just its biocultural preconditions but their historical development and the history of theological-political subversion. Unfortunately, Wolfe’s argument treats Christianity, nationalism, politics, and civil government in generic, free-floating terms altogether detached from the biocultural history and theological presuppositions of any particular Christian nation.

Christian Meier observes that “ever since the Renaissance it has been possible to use the word politics to designate any action of which the state is capable.” Wolfe simply assumes that this modern sense of the term effectively delimits its meaning, past, present, and future. In classical Athenian democracy, however, the polis became identical with its citizens and “the majority of citizens gained supreme authority (with the help of those nobles who placed themselves in their service).” For Aristotle, the word political meant “appropriate to the polis.” His concept of politics denoted it as “the science of the highest good attainable through human action.” Politics presupposed the unity of the citizenry as a whole: “the general civic interest…transcended all particularist interests.” As a consequence, “there was no way in which anything resembling a state could establish centralized power or state institutions that were divorced from society.”[xxviii]

This great experiment in participatory politics rested on the “importance of familial and religious piety in Athenian democracy.” Indeed, “those who failed in their familial, religious, or military duties” could be excluded from the polis. The civic unity of the polis “was founded on family, patriarchy, community, military courage, common ancestry, and an intense patriotism.” Indeed, it has been said that Athenian democracy was based upon a prototype of “racial citizenship.” In contrast to other Greeks, “Athenians claimed to be racially pure…having supposedly sprung from the Attic soil as true autochtones.” Bolstered by that myth of autochthony, the direct democratic politics associated with Athenian citizenship “was grounded in strong racial identity and pride in one’s lineage.” In short, Athens was “a spirited and nativist democracy” in which even prominent residents not of Athenian blood (such as Aristotle) were excluded from citizenship.[xxix]

There was also an important geopolitical dimension to the character of the Athenian polity. This can be seen in the contrast between Athens and Sparta. In the eyes of an imperial power such as the mighty, multinational, military monarchy of Persia, Athens and Sparta represented a Greek power which “was that of patriotic, fractious little republics, defined by civic freedom.” The particular forms of civic power in each city-state emerged out of very different geopolitical circumstances. Sparta was a land power characterized by autarchy, hierarchy, community, and a rigorous military discipline organized to guard against the danger of rebellion by an enslaved population of helots. Athens was a sea power in which international trade and a strong navy encouraged a commercial culture, democracy, individualism, and technology.[xxx]

Guillaume Durocher suggests that “Athens embodied the long-term superiority of dynamic commercial, democratic-individualist, and technologically advanced systems over static, austere, hierarchical-communitarian, and primitive ones.” Like the modern, Anglo-Saxon thalassocracies in Great Britain and the United States, Athens was “dynamic and expansive in peacetime” while “able to adopt sufficiently hierarchical-communitarian characteristics in wartime.”[xxxi]

At the same time, the high level of social solidarity in both polities and its vital contribution to their respective war-fighting abilities gave the Greeks a sophisticated and distinctive understanding of the friend-enemy distinction. A bright-line distinction was drawn between one’s enemies inside the polis and outsiders threatening society as a whole. The modern German jurist Carl Schmitt identified the difference between friend and foe as the existential essence of politics. He took note of the gradations in the Greek understanding of enmity encoded in the koine dialect of ancient Greek and later carried over into the New Testament. Unfortunately, the linguistic precision of the Greek original was lost when translated into English or German. As we have seen, Wolfe relies upon English versions of Reform theology for his rare forays into biblical exegesis. He may never have recognized, therefore, that the (mis)translation of Matthew 5:43-44 conceals a fundamental fault line between idealist and realist political theologies.

When Jesus enjoined his followers to “love your enemies,” he was not laying the moral foundation of Christian pacifism. Wolfe is no pacifist, however; he vigorously defends the martial virtues “as a necessary feature of masculine excellence.”[xxxii] Nevertheless, like most Christians, Wolfe strenuously resists the temptation to build our identities by discriminating between “us” and “them.” Having internalized the anti-discrimination ethos of the civil rights revolution, many Christians mistakenly believe that Jesus asked his followers to “love” their persecutors. As a matter of fact, he merely urged them to “pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you” (Matt.5:44). Carl Schmitt took a more realistic view of the Sermon on the Mount. He tackled the translation issue, clarifying what Jesus meant when asking his audience to love their “enemies.” In the Greek original, Jesus uses the word echthroi to denote persons who might be “private” or “personal” enemies of their fellow citizens (or, in this context, fellow Jews engaged alongside him in a spiritual battle to fulfill the law of Old Covenant Israel). He was not talking about the “public” or “alien” enemies (polemoi) of the Jewish people as a whole.[xxxiii]

Unless one keeps that distinction in mind, Christian charity can easily degenerate into a pathological altruism incapable of addressing existential threats to one’s nation as such. Christian nationalism should be based upon a realist political theology which, in turn, should ground itself in a multi-dimensional understanding of the history and biocultural foundations of every Christian nation.

The Origins and Ends of Mankind in History and Christian Mythology

History can be understood as an intellectual discipline providing narrative or analytical accounts of past events based upon the empirical investigation of more or less reliable sources. It is worth noting that “scientific” history in this sense was the product of two Greeks writing in the fifth century BC. According to R.G. Collingwood, Herodotus and Thucydides “quite clearly recognized both that history is, or can be, a science and that it has to do with human actions.” Their histories were not legends; they were research. They were “an attempt to get answers to definite questions about matters of which one recognizes that one is ignorant.”[xxxiv] Nothing could be further from this methodology than Wolfe’s universal, one size fits all, and thoroughly unscientific schema of salvation history.

Needless to say, the study of human biocultures is also a scientific enterprise which relies upon the empirical study of interactions between biological and cultural phenomena as they have evolved within various population groups. By contrast, Wolfe’s account of Christian nationalism simply presupposes a neo-Augustinian vision of the divinely-ordained stages of the salvation history of mankind, a generic “Christian narrative of creation, fall, redemption, and glorification.”[xxxv] This story presents the past, present, and future of humanity in general as it unfolds in four stages: a state of integrity; a state of sin; a state of grace; and, finally, the state of glory.

Wolfe’s speculative account of the prelapsarian state of integrity is truly breathtaking in what one critic describes as its intellectual irresponsibility. He spends an entire chapter describing the sort of “civil fellowship” that Adam’s progeny would have arranged but for the fall. As Bob Stevenson observes, Wolfe’s vision of the prelapsarian world rests on the biblical account found in

61 verses, comprised of 1,253 words describing the world before our first parents saw the goodness of the forbidden fruit, took and ate. If we only include the parts where humanity exists—and thereby human society, sociability, diversity of gifts, normative roles etc.—that number is reduced to 36 verses, consisting of 764 words.[xxxvi]

It is impossible to construct an account of what a counter-factual prelapsarian world would look like on the basis of those 764 words. Wolfe’s uses his own reason and imagination to reconstruct the structure of the unfallen world that might have been. Wolfe contends that families, tribes, nations, and cultural diversity would all have been natural in the original state of integrity. So, too, would have been hierarchy and the need for the masculine leadership and the martial virtues essential to self-preservation. Wolfe’s portrait of the state of integrity calls to mind the image of the sinless noble savage and is equally devoid of evidence grounded in physical or cultural paleo-anthropology. Wolfe appears to be one of those Christians for whom it has long been “standard doctrine that every member of the human race is descended from the biblical Adam.” How interesting, therefore, that it was a seventeenth-century “Calvinist of Portuguese Jewish origin from Bordeaux” who challenged Christian orthodoxy with the “beguilingly simple” claim “the human beings existed before the biblical Adam.”[xxxvii]

The impact of Isaac La Peyrère (1596–1676) on theological hermeneutics was such that many modern Christian scholars now accept that, in Hebrew hermeneutics, Adam need not be, and probably was not conceived as the first human being (see also Andrew Joyce’s comments, here and here). On that reading, sin was in the world well before Adam. Adam’s story was not about universal human origins but rather about the origins of Israel. Having been created at the exodus and brought to the promised land of Canaan, Israel was bound by a law which it disobeys, suffering exile as a consequence. In this way, “Israel’s drama—its struggles over the land and failure to follow God’s law—is placed into primordial time.”[xxxviii] In other words, the biblical Adam is better understood in mythical terms as proto-Israel.

In any case, after the fall, according to Wolfe’s rendition of the orthodox Reformed hermeneutic, the world becomes subject for the first time to sin, creating the need to augment the powers of civil government to suppress sin and maintain civil order. With the advent of Christ, however, the redemption of mankind becomes possible and “Christians take up the task of true and complete humanity.” Wolfe contends that “restorative grace sets the redeemed apart on earth—constituting a redeemed humanity on earth—and, on that basis, Christians can and ought to exercise dominion in the name of God.” In that way, “grace perfects nature.” Christians “are perfected for heavenly life but also restored in their perfection for obedience in earthly life.”[xxxix] Wolfe never considers the possibility that the mission of the historical Jesus was limited in scope: i.e., the redemption of Old Covenant Israel, not humanity at large.

[i] Few people were ever prosecuted for blasphemous libel in Canada, the last in 1935. This was probably a consequence of the giant loophole in s. 296(3) of the Criminal Code: “No person shall be convicted of an offence under this section for expressing in good faith and in decent language, or attempting to establish by argument used in good faith and conveyed in decent language, an opinion on a religious subject.” There is a similar exemption [see, s. 319(3)(1)(c)] in the recently enacted law prohibiting denial, downplaying, or condoning of the Holocaust. One might reasonably expect more vigorous efforts to be pursued by organized Jewry in contesting the application of that exemption clause whenever cases of public skepticism or outright denial of the Holocaust are deemed threatening to their theopolitical interests.

[ii] James Kurth, “The Protestant Deformation and American Foreign Policy,” (1998) 42(2) Orbis 221, at 225-226.

[iii] Ibid., 227.

[iv] Perry Miller, “The Half-Way Covenant,” (1933) 6(4) New England Quarterly 676.

[v] Kurth, “Protestant Deformation,” 229, 236.

[vi] Eric P. Kaufmann, The Rise and Fall of Anglo-America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 95-98.

[vii] Eugen McCarraher, Christian Critics: Religion and the Impasse in Modern American Social Thought (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000), 15.

[viii] Kurth, “Protestant Deformation,” 237.

[ix] For the common law background to s.296 of the Criminal Code (as it then was) and an illustration of the liberal conventional wisdom successfully calling for its repeal ten years later, see Jeremy Patrick, “Not Dead, Just Sleeping: Canada’s Prohibition on Blasphemous Libel as a Case Study in Obsolete Legislation,” (2008) 41 University of British Columbia Law Review 193.

[x] Stephen Wolfe, The Case for Christian Nationalism (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2022).

[xi] Ibid., 435-438.

[xii] Ibid., 443, 447-448.

[xiii] Ibid., 454-455.

[xiv] Ibid., 31.

[xv] Ibid., 448, 454.

[xvi] Ibid., 455-456.

[xvii] Ibid., 4-5.

[xviii] Neema Parvini, “Christian Nationalism Is a Political Fantasy” December 1, 2022 https://chroniclesmagazine.org/view/christian-nationalism-is-a-political-fantasy/; see also, The Populist Delusion (Perth: Imperium Press, 2022).

[xix] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 433.

[xx] Ibid., 9.

[xxi] Ibid., 11.

[xxii] Ibid., 15.

[xxiii] Augustine, City of God Against the Pagans, ed. And trans. R.W. Dyson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), bk. XX, ch.1, 965.

[xxiv] Cf., Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, (Radford, VA: Wilder Publications, 2013), 12-14, 22.

[xxv] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 89, 180.

[xxvi] Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958), 36, 40-44; see also, Hanna Fenichel Pitkin, The Attack of the Blob: Hannah Arendt’s Concept of the Social (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

[xxvii] Christian Meier, The Greek Discovery of Politics trans. David McLintock (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

[xxviii] Ibid., 14, 20-21.

[xxix] Guillaume Durocher, “Athens: A Spirited and Nativist Democracy,” (Fall 2018) 18(3) The Occidental Quarterly, 74-75, 78; See also, Susan Lape, Race and Citizen Identity in the Classical Athenian Democracy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), ix, 59.

[xxx] Ibid., 72.

[xxxi] Ibid., 73, 80.

[xxxii] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 76.

[xxxiii] Cf. Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political trans. George Schwab (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1976), 28-29.

[xxxiv] R.G. Collingwood, The Idea of History (London: Oxford University Press, 1961), 17-18.

[xxxv] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 41.

[xxxvi] Bob Stevenson, “The Case for Christian Nationalism: A Review (Part Two).” https://bobstevenson.net/the-case-for-christian-nationalism-a-review-part-ii-84384e87eab1

[xxxvii] David N. Livingstone, Adam’s Ancestors: Race, Religion, and the Politics of Human Origins (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 5, 26,33.

[xxxviii] Peter Enns, The Evolution of Adam: What the Bible Does and Doesn’t Say About Human Origins (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2012), 65-66.

[xxxix] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 100, 101, 110-111.

I was sympathetic to the project. Contemporary man has no idea how unusual his moral notions appear within a broad historical context. This characteristically modern form of ignorance has been called the “provincialism of time,” and one of the purposes of education is overcoming it to some degree. Browsing such an anthology might even have therapeutic value for some of our contemporaries.

I was sympathetic to the project. Contemporary man has no idea how unusual his moral notions appear within a broad historical context. This characteristically modern form of ignorance has been called the “provincialism of time,” and one of the purposes of education is overcoming it to some degree. Browsing such an anthology might even have therapeutic value for some of our contemporaries.

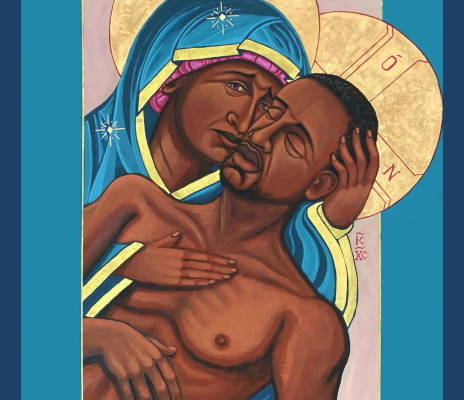

Blatant blasphemy: The violent criminal George Floyd is portrayed as Christ

Blatant blasphemy: The violent criminal George Floyd is portrayed as Christ  Justin Welby, a

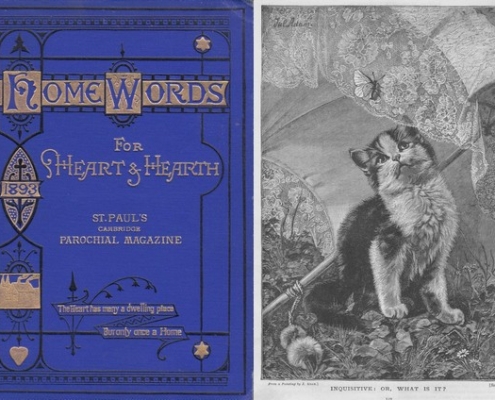

Justin Welby, a  Race-blind universalism from the Church of England in 1893

Race-blind universalism from the Church of England in 1893 Whites are susceptible to sentimentality: a kitten from Home Words for Heart and Heath

Whites are susceptible to sentimentality: a kitten from Home Words for Heart and Heath