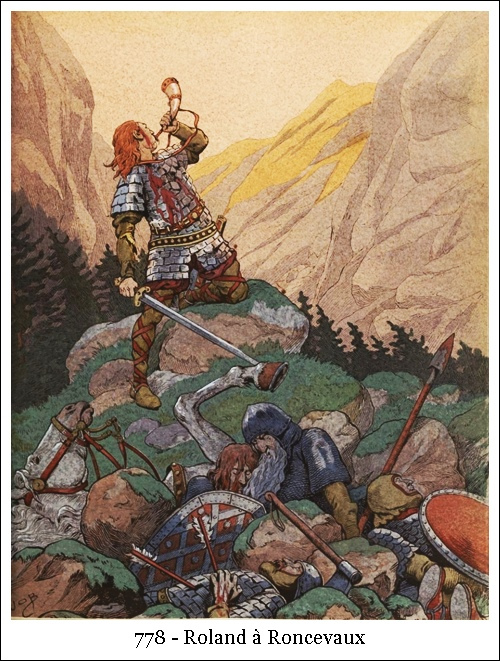

“The Mightier Our Blows, the Greater Our Emperor’s Love”: The Crusader Ideology of Germanized Christianity in the Song of Roland

There is a mysterious quality to the first literature of any ancient nation. The earliest recorded poems are those produced right at the edge between the forceful spontaneity of barbarism and the dead letter of civilization. They almost invariably reflect a primordial and manly mindset very different from that of our own time. They express the psychology and values of conquering peoples, heeding closely to the law of life, by which nations prosper or die. So it is with the Iliad of ancient Greece,the Beowulf of the Anglo-Saxons, and the Song of Roland of the French.

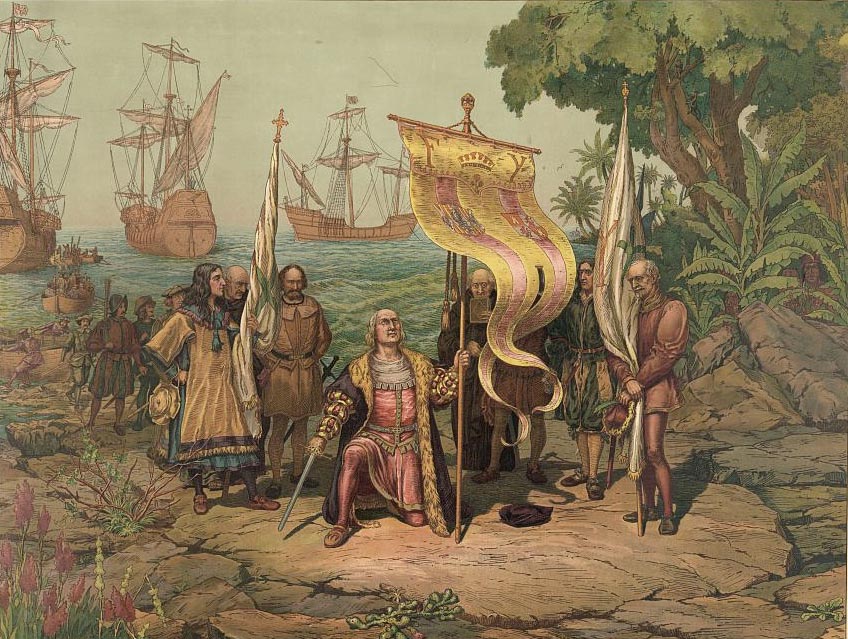

The Song of Roland is the French national epic and the first great piece of French literature, emerging in the eleventh century, on the back of the First Crusade to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims. The poem’s author is even more mysterious than Homer, for we do not even know his name. The Song is a vivid and powerful expression of the values of medieval European chivalry and indeed of the centuries-long clash of civilizations between Christianity and Islam, dating back to the Muslim conquests of Roman Christian Levant and North Africa.

In contrast with later criticisms of Christianity as embodying a universalist “slave-morality,” in the Song we find Christian values perfectly fused, and perhaps subordinated to, the essentially Germanic warrior ethos of the French knightly aristocracy in the form of a novel crusader ideology. The Song presents a perfect case-study of what James C. Russell called the “Germanization of early medieval Christianity” or what William Pierce called “Aryanized” Christianity.[1] The heroes of the poem are obsessed with honor, family, nation, religion, and service to the emperor. I shall present the historical Charlemagne and the values of the Song of Roland. These can help us understand both the emergence and defense of European identity in past centuries. Read more

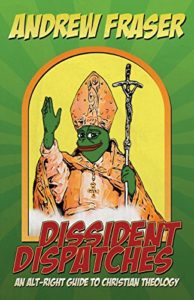

Dissident Dispatches: An Alt-Right Guide to Christian Theology

Dissident Dispatches: An Alt-Right Guide to Christian Theology