False Gods: The Jerusalem Memoirs[1]

Adolph Eichmann

Black House Publishing, 2015

From the Amazon blurb:

In False Gods Eichmann states: “I shall describe the genocide of the Jews, how it happened and give, in addition, my thoughts of the past and of today. For not only did I have to see with my own eyes the fields of death, the battlefields on which life died away, I saw much worse. I saw how, through a few words, through the mere concise order of an individual to whom the state gave authority, such fields for the extinction of life were created. I saw the machinery of death. Grasping cogs within cogs, like clockwork. I saw those who observed the process of the work; and during the process. I saw them always repeating the work and they looked at the seconds-hand, which hurried; hurried like life to death. The greatest and cruellest dance of death of all time. That I saw. And I prepare to describe it, as a warning”. Adolf Eichmann

Adolf Eichmann (1906–1962) was born in Solingen in Germany to Adolf Karl Eichmann[2] and Maria Eichmann, née Schefferling. After his mother died in 1914, his family moved to Linz in Austria. Eichmann began working in his father’s mining company in 1923 and, from 1925 to 1927, worked as a sales clerk for the Oberösterreichische Elektobau company. He also served as district agent in the Vacuum Oil Company.

As a young man, Eichmann joined the German Austrian Young Frontline Soldiers’ Association, which was the youth wing of the paramilitary Frontline Soldiers’ Association of Hermann Hiltl. On the advice of his family friend Ernst Kaltenbrunner, he joined the Austrian branch of the NSDAP and was enlisted as an SS man in 1932. Shortly after the seizure of power of the NSDAP in January1933, Eichmann was dismissed from the oil company, and as a result he devoted all his time to working with the National Socialist party. He was promoted to SS Scharführer in November 1933 and served in the administrative staff of the Dachau concentration camp. In 1934 he moved to the Security Service and, after briefly working in the Freemasonry department, moved to the Jewish department in Berlin in November 1934.

In 1937, he travelled with his superior Herbert Hagen to the British Mandate territory of Palestine to assess the possibility of Jewish emigration from Germany to Palestine. In 1938, after the Anschluss, Eichmann was posted in Vienna and was entrusted with the establishment of a Central Office for Jewish Emigration In the course of this assignment Eichmann developed numerous contacts with Jewish authorities who helped him speed up the emigration of Jews from Austria. In December 1939, he was made head of division IV B 4 of the newly formed Reich Security Head Office (RSHA) and worked, under Heinrich Müller, on Jewish matters. By 1941 Eichmann had been promoted to SS Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) and was entrusted with the organisation of the deportation of the European Jews to various concentration camps in the Greater German Reich.

Although arrested at the end of the war by the U.S. army, Eichmann succeeded in escaping from U.S. custody early in 1946 and lived unnoticed in Germany and Austria until 1950, when he travelled to Argentina, through Italy, under the false name of Ricardo Klement. For the next ten years he worked at mechanical jobs in Buenos Aires and, in 1952, brought his family over to Argentina from Germany. However, in 1953, Simon Wiesenthal obtained a letter to an Austrian, Baron Heinrich Mast, from a German officer in Argentina who reported that he had met Eichmann, who was working at that time in a power plant near Buenos Aires.[3] Although this information was conveyed to the Israeli consul in Vienna as well as to Dr. Nahum Goldmann of the World Jewish Congress in New York, it was 1957 before the Mossad was involved in the search for Eichmann. Walter Eyan of the Israeli Foreign Ministry was informed by the German public prosecutor Fritz Bauer that Eichmann was living in Argentina and he then relayed this information to Isser Harel,[4] the head of Mossad, whose agents succeeded in tracing Eichmann to Argentina and capturing him, three years later, on May 11, 1960. On May 21 he was flown to Israel, where he was tried by the Israeli Court in 1961,[5] found guilty and hanged on May 31, 1962.

* * *

During his stay in Argentina as well as during his internment in Israel, Eichmann dictated and wrote many versions of his memoirs.[6] In Argentina, from 1951 until 1959, he made a series of tape-recorded interviews with the former SS Dutchman Willem Sassen. The transcript of these interviews was obtained in 1991 by the historian David Irving, who then deposited it in the federal archives at Koblenz.[7] Irmtrud Wojak, who has studied these records, has established that seven reels of tape of the Sassen interviews have still to be transcribed. When the Israeli prosecutor Gideon Hausner wished to have the full Sassen transcripts admitted into evidence during Eichmann’s trial in 1961, Eichmann opposed this claiming that this record was mere “pub talk” since he had been drinking red wine during the interview and Sassen had constantly encouraged him to embellish his accounts for journalistic sensation and had even falsely transcribed the interview.

Portions of the Sassen interview were sold by Sassen to Life magazine, which published them in December 1960 (Life, Vol.49, no. 22, November 28, 1960 and no. 23, December 5, 1960), that is, after Eichmann had already been taken to Israel.

Another set of transcriptions of these interviews was taken by Eichmann’s widow Veronika to the Nuremberg defence lawyer, Dr. Rudolf Aschenauer,[8] whom she commissioned to edit the transcripts for publication. This edition by Dr. Aschenauer — which I have also translated[9] — was published by Druffel Verlag in 1980 as Ich, Adolf Eichmann: Ein historischer Zeugenbericht (I, Adolf Eichmann: A historic Testimony), a title suggested to the press by David Irving.[10] In the Foreword and Preface to this edition, Eichmann declares that this is indeed the only testimony that he wishes to be considered as genuine and not dictated under duress. However, this version does not contain certain episodes that the complete Sassen records include such as the accounts of his having witnessed a mass shooting in Minsk in late 1941 or a gassing operation in Chelmno in late 1941/early 1942.[11] It is not clear if these omissions were due to Eichmann’s widow’s wishes or to Dr. Aschenauer himself, who asseverates in his foreword merely that “Where a few cuts have been made, this occurred without any loss in the testimony” However, Dr. Aschenauer did provide, in a supplement to his edition, several original documents from the Reich which detail the frightful severity of the reprisal measures undertaken against Jews and partisans during the war.

During his detention and trial in Jerusalem, Eichmann wrote two further memoirs. The first was begun during his pretrial interrogations with Avner Less and comprised a 127–page handwritten testimony which he called “Meine Memoiren” (My Memoirs). These were later published in Germany by Die Welt between August 12 and September 14, 1999.[12]

After the conclusion of his courtroom testimony and before the delivery of his verdict in December 1961, Eichmann wrote, in August of that year, another handwritten autobiography that he wished to call “Götzen” (False Idols) or “Gnothi Seauton” (Know thyself), which ran to some 500 pages plus another 100 pages of notes and concluded with a long philosophical meditation. This record was guarded in the Israeli State Archives for nearly forty years and was released only during the Irving-Lipstadt trial in London in 2000.[13]

These final memoirs of Adolf Eichmann are more concise than the Argentina account edited by Dr. Aschenauer although they follow the same plan of an initial biographical sketch followed by a record of the deportations he conducted by country.[14] Like the earlier memoirs, the last also presents a detailed account of his career in the SS and Gestapo as the divisional head in charge of the numerous deportations of the European Jews. Through a perusal of Eichmann’s memoirs, the reader will undoubtedly be able to ascertain the scope of the anti-Jewish measures undertaken in the Third Reich. What is especially noteworthy in this account is the enormous organisational framework of this undertaking involving hundreds of political, military and police officials, and their states, across the continent. At the same time, Eichmann highlights his own constant efforts to help the Jews find an independent home territory — even, indeed, during his last posting in Hungary towards the end of the war.

However, compared to the Argentinian memoirs, the present memoirs reveal an extremely sharp disillusionment with the National Socialist goals he championed during the Reich as well as a greater sympathy with the post-war attempts to establish a non-nationalistic one-world order. Although he had joined the NSDAP in order to defend Germany from the humiliation of Versailles, incidents such as the Reich Night of Broken Glass caused him early in his career to realise that he had followed “false idols”, a suspicion that was confirmed by his visits to Lublin and Auschwitz to witness mass killings of Jews. It is interesting also, in this context, that he is, in this version of his memoirs, more honest in his account of certain events such as, for example, the development of the ghetto in Theresienstadt. For, whereas in the Argentinian memoirs[15] he had suggested that it was actually a model old-age home that he himself had done much to develop, he now admits that it was not really meant by Himmler to be an exemplary ghetto but was rather a “camouflage” to deceive the outside world on the manner in which the Reich was dealing with its Jewish problem.[16]

In his Argentinian memoirs, besides, Eichmann had pointed to the contrary effects of the post-war democratic propaganda and re-education on former National Socialists in a derisory manner:

Twelve years of re-education propaganda and occupation-dictatorship have made people who would be considered as witnesses for the defence, if they are not dead or have not been killed, so afraid that they do not wish to know anything at all, or remember about anything any more. Very many would have been, in 1945 and 1946, still ready for a clear statement even under the pressure from the occupation powers, for every pressure releases a counter-reaction. But, today, that option is no longer available. For, the good life and “democratic re-education” have borne fruits, so that today, as a defendant, I would not know which witnesses for the defence would actually be pertinent. In 1945, I would, as a defendant, have had all my colleagues; today, I am no longer sure of that; one part of them will not come into question at all as witnesses for the defence because they are concerned for their survival. And another part has had to lead such a hard life in the meantime that they curse the past and the “stupidity” of having been a National Socialist.[17]

Now, in the present memoirs, Eichmann himself shows very little sympathy for the National Socialist world-view, which he now considers to have been “something half-baked, something cobbled together from all possible ideas and imaginations” and held together as a totalitarian “collective” system through the military principles of command and obedience. In the Argentinian memoirs he had indeed expressed a strong sympathy for Zionist ideals as a mirror-image of National Socialist ones:

Generally, Ben Gurion follows nothing but what the SS Reichsführer also did; the Jewish “Pioneers” root themselves in the soil and have, next to the plough, their gun ready at hand; they are the Israeli translation of our idea of “soldier peasants”. The National Socialist ancestral farm legislation represented similar norms as the “Jewish Development League”, for example, the inalienability of farming land. The organised youth presents a similar image as our National Socialist youth and is likewise the youth of a people in a state of emergency. So I often said to the Jewish representatives well known to me: “If I were a Jew, then I would be the most committed Zionist that you could imagine.” Already as the specialist in the SDHA on the World Zionist Organisation I recognised the parallels between the goals of the SS with its blood and soil ideas and Zionism; in this goal SS and Zionism are siblings.[18]

Now, he abjures nationalism itself as a primitive instinct and considers that

Mutual mistrust, the striving for domination of one over the other, grouping of men according to values and classifications, all this is from now on part of the old rubbish.

He goes so far as to suggests that such ideologies must be totally eradicated:

That is why I said that evil must be extirpated basically, radically. The organisational form that can bring men to such conflicts must be removed. In mutual coexistence man does not have to accommodate himself to the organisational form but the organisational form must be tailored to man. This alone seems to be a practical application based on the bleak experiences up to now; the other is, I think, heretical nonsense. Good perhaps for inner edification, but what is the use of this when murder and annihilation can continue to be ordered by the state.

The remedy for nationalisation is of course internationalisation: “only an internationalisation of peoples overcomes the existing basic instincts, at least one part of the additional hotbeds artificially created by men through nationalisation.” Eichmann even goes so far as to embrace what we now recognise as the globalist ideal of a world-government:

The task of regional governments, which will then have only a provincial character, will be to make the nations of the earth happier in union with the central authority. And the sooner such a thing is achieved the more the personal security and independence of the individual is provided for, and every oppression of him will be prevented.

This abjuration of National Socialism seems not to be the mere result of the broad public discussion of the events of the Reich during his trial or of his fear of a death sentence. The final part of the memoirs in which he meditates on political and philosophical issues also evokes the serenity that he seems to have discovered in the last days of his extraordinary life. As he states, “I have finally found a world-view for myself which satisfies me”.

Today, having an open mind, no anxious skulking, a lack of prejudice, no envy and no hatred are the most important advantages. Of course, I am still an egoist, but this time not at the cost of others. Now even my fellow human beings take part in this egoism with advantages to themselves.

Whatever his reasons for the aversion that he developed to nationalism between the writing of the Argentinian memoirs and that of his final manuscript, a common strand in both memoirs is Eichmann’s consistent insistence on his absolute freedom from “legal guilt” — even though he may well have had reason to feel personal “moral guilt”. For, — as he repeatedly declares — while he had, in the course of his extraordinary life, been forced to witness “death and the devil”, he had never on any occasion participated more closely in this “hell” than as a mere “recipient of orders”.

[1] Taken from Adolf Eichmann, False Gods: The Jerusalem Memoirs, tr. Alexander Jacob, Black House Publishing, 2015.

[2] This is the name testified by Adolf Eichmann in the Israeli Court. However, in his memoirs written in Israel entitled “Götzen” Eichmann gives his father’s name as ‘Wolf’, which was perhaps a pet name.

[3] See the Simon Wiesenthal website:

http://www.simon-wiesenthal-archiv.at/02_dokuzentrum/02_faelle/e01_eichmann.html

[4] In 1975, Isser Harel published a Hebrew account of the search for Eichmann which was translated into English as The House on Garibaldi Street: The Capture of Adolf Eichmann, London: Deutsch, 1975.

[5] The pre-trial interrogations conducted by Avner Less between May 1960 and early 1961 have been published in two of the Israeli Ministry of Justice’s 9-volume set called The Trial of Adolf Eichmann. The courtroom testimony and cross-examination that took place between June 20 and July 24, 1961 constitute another volume of this work. The entire trial was televised and, in March 2011, the Israeli government put out this recording in 114 ‘sessions’ on Youtube.

[6] For studies of Eichmann’s memoirs, see Irmtrud Wojak, Eichmanns Memoiren: Ein kritischer Essay, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch, 2004, and Christopher Browning, Collected Memories: Holocaust History and Post-war Testimony, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003, Ch.I: ‘Perpetrator Testimony: Another Look at Adolf Eichmann’.

[7] However, David Irving has posted a small part of it on his website: http://www.fpp.co.uk/Auschwitz/Eichmann/Buenos_Aires_MS.html

[8] Dr. Rudolf Aschenauer (1913-1983) served as defense lawyer in several Nuremberg trials and other German trials of war criminals from 1947 to 1968.

[9] Adolf Eichmann, The Eichmann Tapes, tr. Dr. Alexander Jacob, Black House Publishing, 2015.

[10] See the David Irving website: http://www.fpp.co.uk/Auschwitz/Eichmann/Sudholt171079.html Irving may have been influenced in his choice of title by Robert Graves’ novel I, Claudius, which had been adapted by the BBC as a successful television serial in 1976. However, it is quite unsuited since Eichmann repeatedly insists in the course of these memoirs that he was not a ‘Caligula’ as the popular press wished to portray him but a mere “cog in the wheel” of a much larger political machinery.

[11] See Christopher Browning, op.cit., pp.17f.

[12] This is available online at the David Irving site: http://www.fpp.co.uk/Auschwitz/Eichmann/DieWelt0899/serial.htmlhttp://www.fpp.co.uk/Auschwitz/Eichmann/DieWelt0899/serial.html

[13]At the moment of writing, it is available online at sites such as http://www.schoah.org/shoah/eichmann/goetzen-2.htm, http://www.nizkor.org/ftp.cgi/people/e/eichmann.adolf/memoire/Eichmann.txt and

ftp://nsl-lager.com/pub/Schriftdateien/Revisionismus/Eichmann,%20Adolf%20-%20Goetzen-Tagebuecher.pdf

[14] Cf. Chapter III of Adolf Eichmann, The Eichmann Tapes: My role in the Final Solution, tr. Alexander Jacob, Black House Publishing, 2015:

‘III: The deportations from abroad

- Serbia

- Romania

- Bulgaria

- Greece

- The Baltic lands

- Croatia

- Italy

- Norway

- Finland

- Denmark

- The Netherlands

- Belgium

- France

- Hungary’

[15] See “Theresienstadt as a model example of ghetto formation”, in Adolf Eichmann, The Aschenauer Memoirs,

[16] All references are to the present edition.

[17]See: “If I were a public prosecutor or defence counsel, whose responsibility would I examine today?” in Adolf Eichmann, op.cit.,

[18] See: “Unity of Jewry in the world?”, in Adolf Eichmann, op.cit.,

“

“ “Hear and obey, goyim!” Jewish judge David Bean overturns a pro-White injunction (

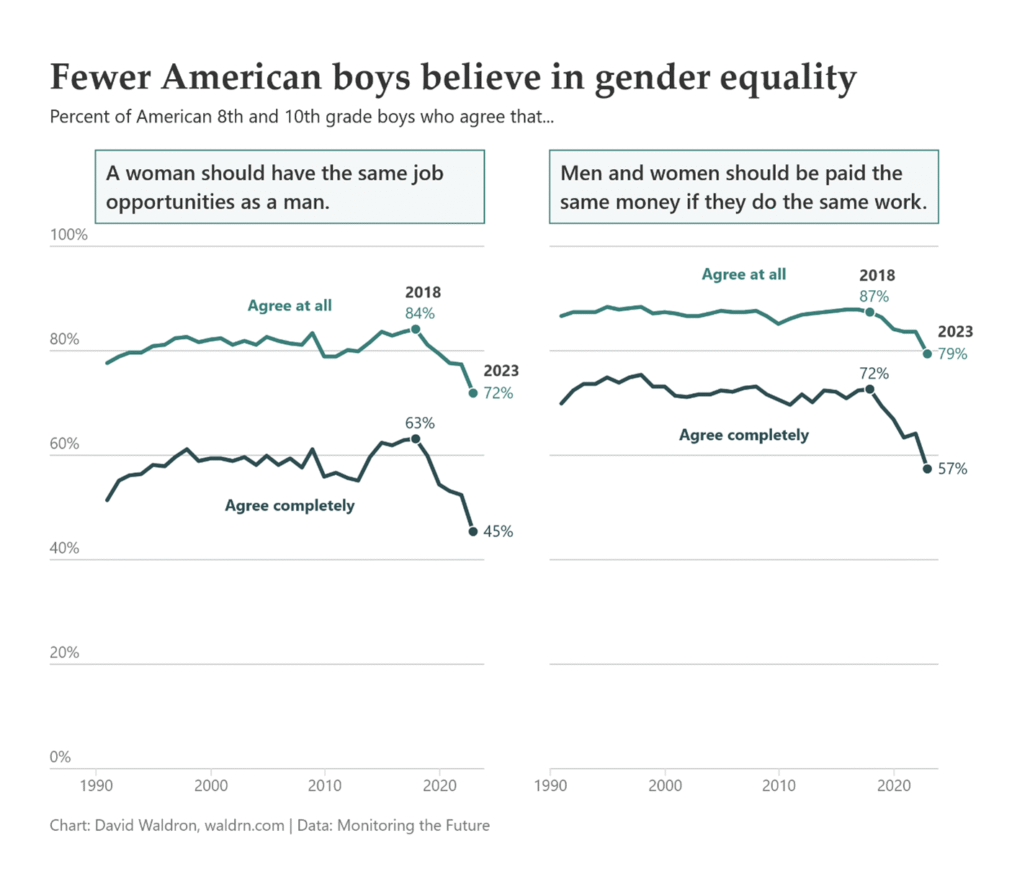

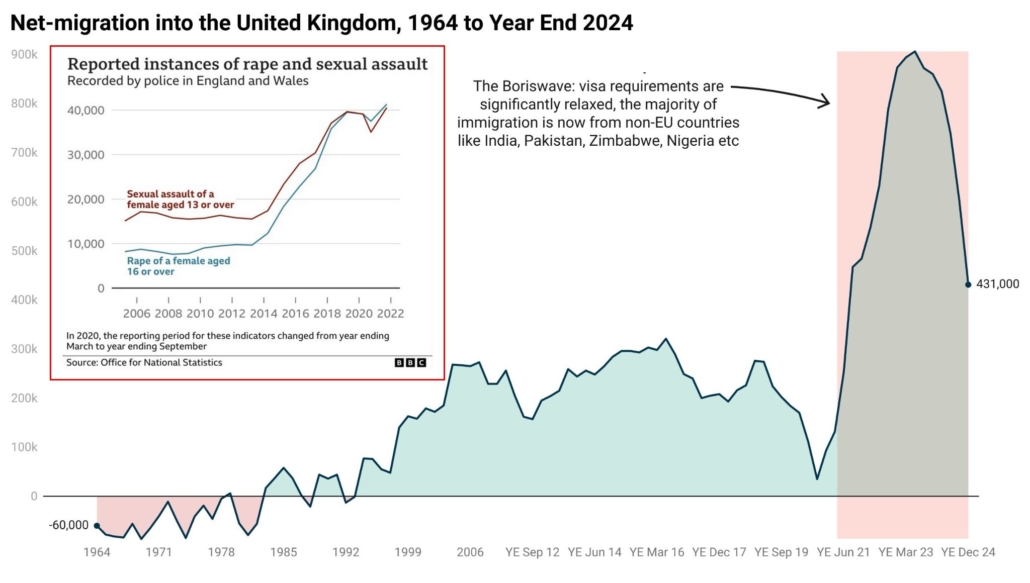

“Hear and obey, goyim!” Jewish judge David Bean overturns a pro-White injunction ( More vibrant migrants = more sexual violence

More vibrant migrants = more sexual violence What’s good for goyim is not good for Jews:

What’s good for goyim is not good for Jews: