Culture of Critique Expanded and Updated

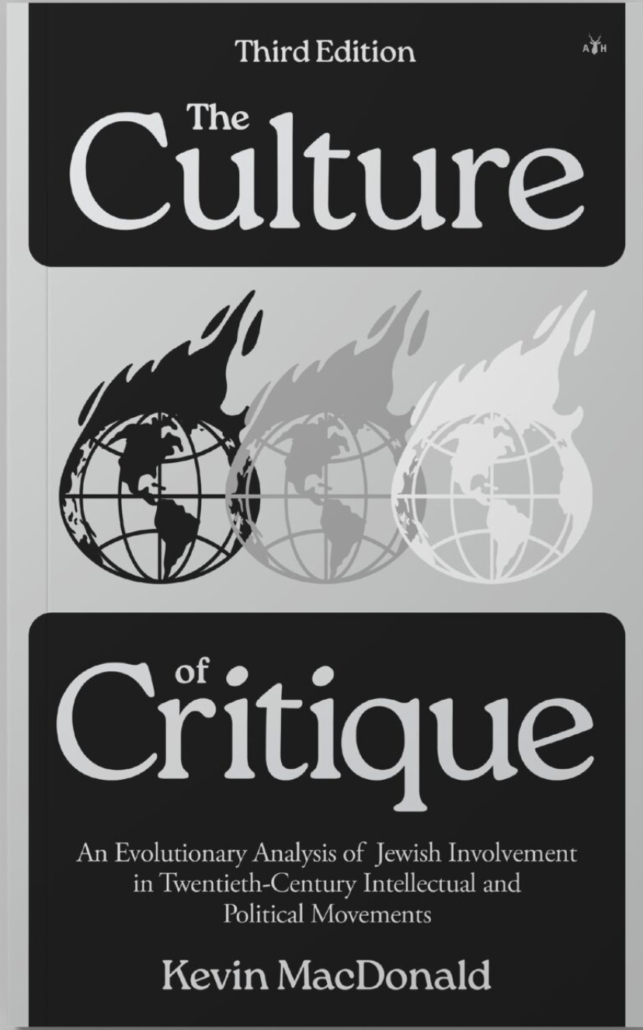

The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements, 3rd edition

The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements, 3rd edition

Kevin MacDonald

Antelope Hill Publishing, 2025 (recently banned on Amazon)

666+c pages, $39.89 paperback

In the later half of the twentieth century, the United States of America—hitherto the world’s most powerful and prosperous country—opened its borders to hostile foreign multitudes, lost its will to enforce civilized standards of behavior upon blacks and other “minority groups,” began enforcing novel “antidiscrimination” laws in a manner clearly discriminatory against its own founding European stock, repurposed its institutions of higher education for the inculcation of radical politics and maladaptive behavior upon the young, and submitted its foreign and military policy to the interests of a belligerent little country half way around the world. In the process, we destroyed our inherited republican institutions, wasted vast amounts of blood and treasure, and left a trail of blighted lives in a country which had formerly taken for granted that each rising generation would be better off than the last. One-quarter of the way into the twenty-first century, the continued existence of anything deserving the name “United States of America” would seem very much in doubt. What on earth happened?

While there is plenty of blame to go around, including some that rightfully belongs with America’s own founding stock, the full story cannot be honestly told without paying considerable attention to the rise of Eastern European Jews to elite status.

This population is characterized by a number of positive traits, including high verbal intelligence and an overall average IQ of 111. They typically have stable marriages, practice high-investment parenting, and enjoy high levels of social trust within their own community. In their European homelands they lived for many centuries in shtetls, closed townships composed exclusively of Jews, carefully maintaining social and (especially) genetic separation from the surrounding, usually Slavic population. This was in accord with an ancient Jewish custom going back at least to the Biblical Book of Numbers, in which the prophet Balaam tells the children of Israel “you shall be a people that shall dwell alone.”

If one wants to preserve social and genetic separation, few methods are more reliable than the cultivation of negative affect toward outsiders. This is what was done in such traditional, religiously organized Jewish communities: gentiles were considered treif, or ritually unclean, and Jewish children were encouraged to think of them as violent drunkards best avoided apart from occasional self-interested economic transactions.

Following the enlightenment and the French Revolution, Jews were “emancipated” from previous legal disabilities, but ancient habits of mind are not changed as easily as laws. One consequence was the attraction of many newly-emancipated Jews to radical politics. Radicals by definition believe there is something fundamentally wrong and unjust about the societies in which they live, which disposes them to form small, tightly-knit groups of like-minded comrades united in opposition to an outside world conceived as both hostile and morally inferior. In other words, radicalism fosters a social and mental environment similar to a shtetl. It is not really such a big step as first appears from rejecting a society because its members are ritually unclean and putative idolaters to rejecting it for being exploitative, capitalist, racist, and anti-Semitic. Jews themselves have often been conscious of this congruence between radicalism and traditional Jewish life: the late American neoconservative David Horowitz, e.g., wrote in his memoir Radical Son: “What my parents had done in joining the Communist Party and moving to Sunnyside was to return to the ghetto.”

By the end of the nineteenth century, the Eastern European Jewish population had grown beyond the capacity of traditional forms of Jewish economic activity to support it, resulting in widespread and sometimes dire poverty. Many turned to fanatical messianic movements of a religious or political character. Then, beginning in the 1890s, an increasing number of these impoverished and disaffected Jews started migrating to the United States. Contrary to a widespread legend, the great majority were not “fleeing pogroms”—they were looking for economic opportunity.

Even so, many Jews brought their radicalism and hostility to gentile society with them to their new homeland, and these persisted even in the absence of legal restrictions upon them and long after they had overcome their initial poverty. Jewish sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset has written colorfully of the countless wealthy and successful American Jewish “families which around the breakfast table, day after day, in Scarsdale, Newton, Great Neck, and Beverly Hills have discussed what an awful, corrupt, immoral, undemocratic, racist society the United States is.”

Over the course of the twentieth century, these smart, ambitious, and ethnically well-networked Eastern European Jews rose to elite status in the academy, the communications media, law, business, and politics. By the 1960s, they had succeeded in replacing the old Protestant ruling class with an alliance between themselves, other “minorities” with grudges against the American majority, and a sizeable dose of loyalty-free White sociopaths on the make. Unlike the old elite it replaced, the new rulers were at best suspicious of—and often actually hostile toward—the people they came to govern, and we have already enumerated some of the most disastrous consequences of their rule in our opening paragraph.

Kevin MacDonald’s The Culture of Critique describes several influential movements created and promoted by Jews during the twentieth century in the course of their rise. It is the best book you will find on the Jewish role in America’s decline. First published by Praeger in 1998, a second paperback edition augmented with a new Preface appeared in 2002. Now, twenty-three years later, he has brought out a third edition of the work through Antelope Hill Publishing. In addition to expanding the earlier editions’ accounts of Boasian Anthropology, Freudian Psychoanalysis, various Marxist or quasi-Marxist forms of radicalism, and Jewish immigration activism, he has added an entirely new chapter on neoconservatism. As he explains:

I argue that these movements are attempts to alter Western societies in a manner that would neutralize or end anti-Semitism and enhance the prospects for Jewish group continuity and upward mobility. At a theoretical level, these movements are viewed as the outcome of conflicts of interest between Jews and non-Jews in the construction of culture and in various public policy issues.

This edition is fully 40 percent longer than its predecessor, yet a detailed table of contents makes it easier for readers to navigate.

* * *

We shall have a detailed look at the chapter on “The Boasian School of Anthropology and the Decline of Darwinism in the Social Sciences,” since it is both representative of the work as a whole and significantly augmented over the version in previous editions.

Anthropology was still a relatively new discipline in America at the beginning of the Twentieth Century, but it enjoyed a promising theoretical foundation in Darwinian natural selection and the rapidly developing science of genetics. Darwinists and Mendelians, however, were opposed by Lamarckians who believed that acquired characteristics could be inherited: e.g., that if a man spent every day practicing the piano and then fathered a son, his son might have an inborn advantage in learning the piano. This idea was scientifically discredited by the 1930s, but long remained popular among Jewish intellectuals for nonscientific reasons, as a writer cited by MacDonald testifies:

Lenz cites an “extremely characteristic” statement of a Jewish intellectual: “The denial of the racial importance of acquired characters favours race hatred.” The obvious interpretation of such sentiments is that Jewish intellectuals opposed the theory of natural selection because of its negative political implications.

In one famous case a Jewish researcher committed suicide when the fraudulent nature of his study in support of Lamarckism was exposed.

Franz Boas was among the Jewish intellectuals to cling to Lamarckism long after its discrediting. He had what Derek Freeman describes as an “obscurantist antipathy to genetics” that extended even to opposing genetic research. This attitude was bound up with what Carl Degler called his “life-long assault on the idea that race was a primary source of the differences to be found in the mental or social capabilities of human groups.” He did not arrive at this position as a result of disinterested scientific inquiry. Rather, as Degler explains, he thought racial explanations “undesirable for society” and had “a persistent interest in pressing his social values upon the profession and the public.”

Boas appeared to wear his Jewishness lightly; MacDonald remarks that he “sought to be identified foremost as a German and as little as possible as a Jew.” Anthropologist and historian Leonard B. Glick wrote:

He did not acknowledge a specifically Jewish cultural or ethnic identity. . . . To the extent that Jews were possessed of a culture, it was . . . strictly a matter of religious adherence. . . . He was determined . . . not to be classified as a member of any group.

Yet such surface appearances can be misleading. From a very early age, Boas was deeply concerned with anti-Semitism and felt alienated from the Germany of his time. These appear to have been the motives for his emigration to America. He also maintained close associations with the Jewish activist community in his new homeland. Especially in his early years at Columbia, most of his students were Jewish, and of the nine whom Leslie White singles out as his most important protegés, six were Jews. According to David S. Koffman: “these Jews tended to marry other Jews, be buried in Jewish cemeteries, and socialize with fellow Jews, all core features of Jewish ethnicity, though they conceived of themselves as agents of science and enlightenment, not Jewish activists.”

Boas was also dependent on Jewish patronage. In the 1930s, for instance, he worked to set up a research program to “attack the racial craze” (as he put it). The resulting Council of Research of the Social Sciences was, as Elazar Barkan acknowledges in The Retreat of Scientific Racism (1993) “largely a façade for the work of Boas and his students.” Financial support was principally Jewish, since others declined solicitations. Yet Boas was aware of the desirability of disguising Jewish motivations and involvement publicly, writing to Felix Warburg: “it seemed important to show the general applicability of the results to all races both from the scientific point of view and in order to avoid the impression that this is a purely Jewish undertaking.”

One of Boas’s Jewish students remarked that young Jews of her generation felt they had only three choices in life—go live in Paris, hawk communist newspapers on street corners, or study anthropology at Columbia. The latter option was clearly perceived as a distinctively “Jewish” thing to do. Why is this?

Many Jews have supplemented Jewish advocacy with activism on behalf of “pluralism” and other ethnic “minority groups.” Boas himself, for example, maintained close connections with the NAACP and the Urban League. David S. Lewis has described such activities as an effort to “fight anti-Semitism by remote control.” And anthropology itself as conceived by Boas was not merely a scholarly discipline but an extension of these same concerns.

Much of the actual fieldwork conducted by Boas and his students focused on the American Indian. In a passage new to this edition, MacDonald quotes from David S. Koffman’s The Jews’ Indian (2019) on the Jewish motivations that frequently lay behind their work:

Jewishness shaped the profession’s engagement with its practical object of study, the American Indian. Jews’ efforts—presented as the efforts of science itself—to salvage, collect, and preserve disappearing American Indian culture was a form of ventriloquism. [Yet they] assumed their own Jewishness would remain an invisible and insignificant force in shaping the ideas they would use to shape ideas about others.

Boasian anthropologists did not draw any sharp distinction between their professional and their political concerns:

Political action formed a part of many anthropologists’ sense of the intellectual mission of the field. Their findings, and the framing of distinct cultures, each worthy of careful attention in its own right, mattered to social existence in the United States. Their scholarship on Native American cultures developed alongside their personal and political work on behalf of Jewish causes.

Koffman highlights the case of Boas’s protegé Edward Sapir:

Sapir’s Jewish background continuously influenced and intersected with his scholarship on American Indians. Sapir’s biography shows a fascinating parallel preoccupation with both Native and Jewish social issues. These tracks run side by side, concerned as both were with parallel questions about ethnic survival, adaptability, dignity, cultural autonomy, and ethnicity.

Some Jews from Boas’s circle of influence even went to work for the US government’s Bureau of Indian Affairs, where they “consistently linked Indian uplift with an articulation of minority rights and cultural pluralism.” In this way, writes Koffman, “Jewish enlightened self-interest impacted the course of American Indian life in the middle of the twentieth century.”

Boas had a number of gentile students as well, of course, especially in the later part of his career. Yet some observers have commented upon differences in the thinking and motivations of his Jewish and gentile followers. While the rejection of racial explanations was a moral crusade for many of the Jews, as it was for Boas himself, his gentile students were more inclined to view the matter simply as a theoretical issue. Alfred Kroeber, for example, once impatiently remarked that “our business is to promote anthropology rather than to wage battles on behalf of tolerance.”

Two of Boas’s best known gentile disciples were Margeret Meade and Ruth Benedict, and it may not be an accident that both of these women were lesbians. As Sarich and Miele write in Race: The Reality of Human Difference (2004): “Their sexual preferences are relevant because developing a critique of traditional American values was as much a part of the Boasian program in anthropology as was their attacks on eugenics and nativism.” More generally, they note, “the Boasians felt deeply estranged from American society and the male WASP elites they were displacing in anthropology.” Jewish or not, they saw themselves as a morally superior ingroup engaged in a struggle against a numerically superior outgroup. In this respect, they formed a historical link between the radical cells and shtetls of the old world and the hostile elite ruling America today.

Boas posed as a skeptic and champion of methodological rigor when confronted with theories of cultural evolution or genetic influence on human differences, but as the evolutionary anthropologist Leslie White pointed out, the burden of proof rested lightly on Boas’s own shoulders: his “historical reconstructions are inferences, guesses, and unsupported assertions [ranging] from the possible to the preposterous. Almost none is verifiable.”

MacDonald writes:

An important technique of the Boasian school was to cast doubt on general theories of human evolution . . . by emphasizing the vast diversity and chaotic minutiae of human behavior, as well as the relativism of standards of evaluation. The Boasians argued that general theories of cultural evolution must await a detailed cataloguing of cultural diversity, but in fact no general theories emerged from this body of research in the ensuing half-century of its dominance of the profession. Leslie White, an evolutionary anthropologist whose professional opportunities were limited because of his theoretical orientation, noted that because of its rejection of fundamental scientific activities such as generalization and classification, Boasian anthropology should be classed more as an anti-theory than a theory of human culture.

Boas brooked no dissent from his followers:

Individuals who disagreed with the leader, such as Clark Wissler, were simply excluded from the movement. Wissler was a member of the Galton society, which promoted eugenics, and accepted the theory that there is a gradation of cultures from lowest to highest, with Western civilization at the top.

Among Boas’s most egregious sins against the scientific spirit was a study he produced at the request of the US Immigration Commission called into being by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1907. This was eventually published as Changes in Bodily Form of Descendants of Immigrants. It maintained the extremely implausible thesis that the skulls of the children of immigrants to the US differed significantly from those of their parents—in spite of the influence of heredity, and due entirely to growing up in America. The paper came to be cited countless times by writers of textbooks and anyone who wished to deprecate the importance of heredity or stress that of environment.

Ninety years later, anthropologists Corey S. Sparks and Richard L. Janz reanalyzed Boas’s original data. While they stop short of accusing him of deliberate fraud, they did find that his data fail to support his conclusions. In MacDonald’s words:

Boas made inflated claims about the results: very minor changes in cranial index were described as changes of “type” so that Boas was claiming that within one generation immigrants developed the long-headed type characteristic of northwest Europeans. Several modern studies show that cranial shape is under strong genetic influence. [Sparks and Janz’s] reanalysis of Boas’s data indicated that no more than one percent of the variation between groups could be ascribed to the environmental effects of immigration.

In short, Boas’s study was not disinterested science but propaganda in a political battle over immigration. At a minimum, he was guilty of sloppy work inspired by wishful thinking.

Boas’s actual anthropological studies, such as those on the Kwakiutl Indians of Vancouver Island, contributed little to human knowledge. But this was not where his talent lay: his true achievement was in the realm of academic politics. He built a movement that served as an extension of himself long after his death, capturing and jealously controlling anthropological institutions and publications, and making it difficult for those who dissented from his scientifically groundless views to achieve professional success. As MacDonald writes:

By 1915 his followers controlled the American Anthropological Association and held a two-thirds majority on its executive board. In 1919 Boas could state that “most of the anthropological work done at the present time in the United States” was done by his students at Columbia. By 1926 every major department of anthropology was headed by Boas’s students, the majority of whom were Jewish.

Boas strenuously promoted the work of his disciples, but rarely cited works of people outside his group except to disparage them. A section new to this third edition explains how his influential student Melville Herskovits also blocked from publication and research funding those not indebted to him or not supporting his positions. Margaret Meade’s fairy tale of a sexually liberated Samoa, on the other hand, became the bestselling anthropological work of all time due almost entirely to zealous promotion by her fellow Boasians at prominent American universities.

Among the more obvious biases of anthropological work carried out by Boas’s disciples was a nearly complete ignoring of warfare and violence among the peoples they studied. Their ethnographic studies, such as Ruth Benedict’s account of the Zuni Indians in Patterns of Culture (1934), promoted romantic primitivism as a means of critiquing modern Western civilization. Works like Primitive War (1949) by Harry Holbert Turney-High, which documented the universality and savagery of war, were simply ignored. As MacDonald explains:

The behavior of primitive peoples was bowdlerized while the behavior of European peoples was not only excoriated as uniquely evil but also as responsible for all extant examples of warfare among primitive peoples. From this perspective, it is only the fundamental inadequacy of European culture that prevents an idyllic world free from between-group conflict.

Leslie White wrote that “Boas has all the attributes of the head of a cult, a revered charismatic teacher and master, literally worshiped by disciples whose permanent loyalty has been effectively established.” MacDonald describes his position as closer to that of a Hasidic Rebbe among his followers than to the leader of a genuinely scientific research program—the results of which can never be known in advance.

Due to the success of Boas’s mostly Jewish disciples in gaining control of institutional anthropology, by the middle of the twentieth century it became commonplace for well-read American laymen to refer to human differences in cultural terms. Western Civilization was merely different from, not better than, the ways of headhunters and cannibals. A vague impression was successfully propagated to the public that “science had proven” the equality of the races; few indeed understood that the “proof” consisted in the scientists who thought otherwise having been driven into unemployment. Objective research into race and racial differences largely ceased, and an intellectual atmosphere was created in which many imagined that the opening of America’s borders to the world would make little practical difference.

* * *

Space precludes us from looking in similar detail at all the book’s chapters, but we must give the reader an idea of the material new to this third edition. Some of the most important is found in an 85-page Preface, and concerns the rise of Jews in the American academic world. Boasian anthropology may be seen in hindsight as an early episode in this rise, but Boas died in 1942 and our main story here concerns the postwar period. As MacDonald writes:

The transformation of the faculty was well under way in the 1950s and by the late 1960s was largely complete. It was during this period that the image of the radical leftist professor replaced the image of the ivory tower professor—the unworldly person at home with his books, pipe, and tweed jacket, totally immersed in discussions of Renaissance poetry.

The old academic elite had been better educated than the public at large, of course, but saw themselves as trustees of the same Christian European civilization, and did not desire radical changes to the society in which they lived. Today’s representative professor “almost instinctively loathes the traditional institutions of European-American culture: its religion, customs, manners, and sexual attitudes.”

This matters, because the academy is a crucial locus of moral and intellectual authority:

Contemporary views on issues like race, gender, immigration are manufactured in the academy (especially elite universities), disseminated throughout the media and the lower levels of the educational system, and ultimately consumed by the educated and not-so-educated public. Newspaper articles and television programs on these issues routinely include quotes from academic experts.

By 1968 Jews, who made up less than three percent of the US population, constituted 20 percent of the faculty of elite American colleges and universities, with overrepresentation most pronounced among younger faculty. Studies found Jewish faculty well to the left of other academics, more supportive of student radicals, and more likely to approve relaxing standards in order to recruit non-White faculty and students. By 1974, a study of articles published in the top twenty academic journals found that Jews made up 56 percent of the social scientists and 61 percent of the humanities scholars.

A possibly extreme but telling example of left-wing bias is Jonathan Haidt’s informal 2011 survey at a convention of social psychologists, reputedly the most left-leaning area of academic psychology. Haidt found only three participants out of 1000 willing publicly to label themselves “conservative.” He acknowledges that this discipline has evolved into a “tribal moral community” that shuns and ostracizes political conservatives, with the result that research conflicting with its core political attitudes is either not performed or is likely to be excluded from peer-reviewed journals.

MacDonald devotes considerable attention to a widely discussed 2012 paper “Why Are Professors Liberal?” by Neil Gross and Ethan Fosse. The authors argue that academics are more liberal than the population at large for three reasons. First and most importantly, due to the higher proportion of academics with advanced educational credentials, an effect they consider independent of the role IQ plays in helping obtain such credentials. MacDonald remarks that this liberal shift may be due either to socialization and conditioning in the graduate school environment or to perceived self-interest in adopting liberal views and/or identifying with an officially sanctioned victim group.

Second, Gross and Fosse believe liberalism results from academic’s greater tolerance for controversial ideas. MacDonald is dismissive of this proposal, writing that in his observation such tolerance does not exist outside the professoriate’s self-conception.

Third, they find that liberalism corelates with the larger fraction of the religiously unaffiliated in the academy. MacDonald points out that many of the religiously unaffiliated are probably Jews, and remarks that the study would have been more informative if race and Jewish ethnic background had been included as variables alongside religious affiliation.

Gross and Fosse acknowledge that their data can be interpreted in a number of ways, but their own argument is that

the liberalism of professors . . . is a function . . . of the systematic sorting of young adults who are already liberally—or conservatively—inclined into and out of the academic profession, respectively. We argue that the professoriate, along with a number of other knowledge work fields, has been “politically typed” as appropriate for and welcoming of people with broadly liberal political sensibilities, and as inappropriate for conservatives.

In other words, academic liberalism is the product of a natural sorting process similar to that which has resulted in a career such as nursing being typecast as appropriate for women. It should be emphasized, however, that much of this sorting is done by the academy itself, not by prospective academics: many professors unhesitatingly acknowledge their willingness to discriminate against conservative job candidates.

The Gross and Fosse study also fails to explore the way the meaning of being liberal or left wing has changed over the years. The academy was already considered left-leaning when the White Protestant ascendency was still intact. But in those days being liberal meant supporting labor unions and other institutions aimed at improving the lot of the (predominantly White) working class.

The New Left abandoned the White working class because it was insufficiently radical, desiring incremental improvements of its own situation rather than communist revolution. The large Jewish component of the New Left, typified by the Frankfurt School, was also shaken by Hitler’s success in gaining the support of German labor. So they abandoned orthodox Marxism in a search for aggrieved groups more likely to demand radical change. These they found in ethnic and sexual minority groups such as Blacks, feminists, and homosexuals. They also advocated for massive non-White immigration to dilute the power of the White majority, leave Jews less conspicuous, and recruit new ethnic groups easily persuadable to cultivate grievances against the dwindling White majority.

Today’s academy is a product of the New Left of the 1960s. While it is more “liberal” (in the American sense) than the general public on economic issues, what makes it truly distinctive is its attitudes on social issues: sexual liberation (including homosexuality and abortion), moral relativism, religion, church-state separation, the replacement of patriotism by cosmopolitan ideals, and the whole range of what has been called “expressive individualism.”

Sorting can explain how an existing ideological hegemony within the academy maintains itself, but not how it could have arisen in the first place. To account for the rise of today’s academic left, Gross and Fosse propose a conflict theory of successful intellectual movements. In particular, they cite sociological research indicating that such movements have three key ingredients: 1) they originate with people with high-status positions having complaints against the current environment, resulting in conflict with the status quo; 2) these intellectuals form cohesive and cooperative networks; and 3) this network has access to prestigious institutions and publication outlets.

This fits Kevin MacDonald’s theory of Jewish intellectual movements to a T. Indeed, since the academic left is so heavily Jewish, we are in part dealing with the same subject matter. Even Gross and Fosse show some awareness of this, as MacDonald writes:

Gross and Fosse are at least somewhat cognizant of the importance of Jewish influence. They deem it relevant to point out that Jews entered the academic world in large numbers after World War II and became overrepresented among professors, especially in elite academic departments in the social sciences.

So let us apply the Gross and Fosse three-part scheme to radical Jewish academics. First, Jews do indeed have a complaint against the environment in which they live, or rather two related complaints: the long history of anti-Semitism and the predominance of White Christian culture.

As MacDonald notes, “it is common for Jews to hate all manifestations of Christianity.” In his book Why Are Jews Liberals? (2009), Norman Podhoretz formulates this Jewish complaint as follows:

[The Jews] emerged from the Middle Ages knowing for a certainty that—individual exceptions duly noted—the worst enemy they had in the world was Christianity: the churches in which it was embodied—whether Roman Catholic or Russian Orthodox or Protestant—and the people who prayed in and were shaped by them.

Anti-Jewish attitudes, however, by no means depend on Christian belief. In the nineteenth century Jews began to be criticized as an economically successful alien race intent on subverting national cultures. Accordingly, the complaint of many Jews today is no longer merely Christianity but the entire civilization created by Europeans in both its religious and its secular aspects.

From this point it is a very short step to locating the source of anti-Semitism in the nature of European-descended people themselves. The Frankfurt School took this step, and the insurgent Jewish academic left followed them. MacDonald writes:

This explicit or implicit sense that Europeans themselves are the problem is the crux of the Jewish complaint. [It] has resonated powerfully among Jewish intellectuals. Hostility to the people and culture of the West was characteristic of all the Jewish intellectual movements of the left that came to be ensconced in the academic world of the United States and other Western societies.

The second item in Gross and Fosse’s list of the traits of successful intellectual movements is that their partisans form cohesive, cooperative networks. All the Jewish movements studied by Kevin MacDonald have done this, as he has been at pains to emphasize. Group strategies outcompete individualist strategies in the intellectual and academic world just as they do in politics and the broader society. It does not matter that Western science is an individualistic enterprise in which people can defect from any group consensus easily in response to new discoveries or more plausible theories. The Jewish intellectual movements studied by MacDonald are not scientific research programs at all, but “hermeneutic exercise[s] in which any and all events can be interpreted within the context of the theory.” These authoritarian movements thus represent a corruption of the Western scientific ideal, yet that does nothing to prevent them from being effective in the context of academic politics.

Finally, Gross and Fosse note that the most successful intellectual movements are those with access to prestigious institutions and publication outlets. This has clearly been true of the Jewish movements Kevin MacDonald has studied, as he himself notes:

The New York Intellectuals developed ties with elite universities, particularly Harvard, Columbia, the University of Chicago, and the University of California-Berkeley, while psychoanalysis and Boasian anthropology became entrenched throughout academia. The Frankfurt School intellectuals were associated with Columbia and the University of California-Berkeley, and their intellectual descendants are dispersed through the academic world. The neoconservatives are mainly associated with the University of Chicago and Johns Hopkins University, and they were able to get their material published by the academic presses at these universities as well as Cornell University.

The academic world is a top-down system in which the highest levels are rigorously policed to ensure that dissenting ideas cannot benefit from institutional prestige. The panic produced by occasional leaks in the system, as when the University of Chicago’s John Mearsheimer teamed up with Harvard’s Stephen Walt to offer some cautious criticisms of the Israel lobby, demonstrate the importance of obtaining and monopolizing academic prestige.

Moreover, once an institution has been captured by the partisans of a particular intellectual perspective, informal scholarly networks become de facto gatekeeping mechanisms, creating enormous inertia. As MacDonald writes: “there is tremendous psychological pressure to adopt the fundamental assumptions at the center of the power hierarchy of the discipline. It is not surprising that people [are] attracted to these movements because of the prestige associated with them.”

What MacDonald calls the final step in the transformation of the university into a bastion of the anti-White left is the creation since the 1970s of whole programs of study revolving around aggrieved groups:

My former university is typical of academia generally in having departments or programs in American Indian Studies, Africana Studies (formerly Black Studies), American Studies (whose subject matter emphasizes “How do diverse groups within the Americas imagine their identities and their relation to the United States?”), Asian and Asian-American Studies, Chicano and Latino Studies, Jewish Studies, and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies. All of these departments and programs are politically committed to advancing their special grievances against Whites and their culture.

Although it is difficult to specify the exact linkage, the academic triumph of Jewish radicals was followed in short order by the establishment of these other pillars of the cultural left within the university.

As MacDonald notes, women make up an important component of the grievance coalition in academia, and not only in the area of “Women’s Studies.” They make up around 60 percent of PhDs and 80 percent of bachelor’s degrees in ethnic, gender and cultural studies.

Overall, compared to men, women are more in favor of leftist programs to end free speech and censor speech they disagree with. They are more inclined toward activism, and less inclined toward dispassionate inquiry; they are more likely to agree that hate speech is violence, that it’s acceptable to shout down a speaker, that controversial scientific findings should be censored, and that it should be illegal to say offensive things about minorities.

Such differences are likely due to women’s evolutionary selection for empathy and fear. No amount of bravado about “smashing the patriarchy” can conceal women’s tendency to timid conformism, and that is precisely what leads to success in academic grievance studies.

Although MacDonald does not consider feminism a fundamentally Jewish movement, many Jewish women have unquestionably played a prominent role within it, and it is marked by the same disregard of biological realities we observed in Boasian anthropology. The new Preface accordingly offers some brief remarks on Jewish lesbian and academic gender theorist Judith Butler. One of her leading ideas is that gender identity is “performative,” and unconstrained by genetic or hormonal influences. This leaves us free to rebel against the patriarchy by engaging in “subversive performances of various kinds.” Obviously, the contemporary transgender movement would count as an example of such a performance.

Jews have been greatly overrepresented in the student bodies of elite American universities for several decades, to a degree that their intelligence and academic qualifications cannot begin to account for:

Any sign that the enrollment of Jews at elite universities is less than about 20 percent is seen as indicative of anti-Semitism. A 2009 article in The Daily Princetonian cited data from Hillel [a Jewish campus organization] indicating that, with the exception of Princeton and Dartmouth, on average Jews made up 24 percent of Ivy League undergraduates. Princeton had only 13 percent Jews, leading to much anxiety and a drive to recruit more Jewish students. The result was extensive national coverage, including articles in The New York Times and The Chronicle of Higher Education. The rabbi leading the campaign said she “would love 20 percent”—an increase from over six times the Jewish percentage in the population to around ten times.

According to Ron Unz:

These articles included denunciations of Princeton’s long historical legacy of anti-Semitism and quickly led to official apologies, followed by an immediate 30 percent rebound in Jewish numbers. During these same years, non-Jewish white enrollment across the entire Ivy League had dropped by roughly 50 percent, reducing those numbers to far below parity, but this was met with media silence or even occasional congratulations on the further “multicultural” progress of America’s elite education system.

The Preface to this new edition of The Culture of Critique also contains additions on the psychology of media influence and Jewish efforts to censor the internet, along with an updating of information on Jewish ownership and control of major communications media.

Chapter Three on “Jews and the Left” includes a new sixteen-page section “Jews as Elite in the USSR,” as well as shorter additions on Jews and McCarthyism, and even the author’s own reminiscences of Jewish participation in the New Left at the University of Wisconsin in his youth. The additions incorporate material from important works published since the second edition, including Solzhenitsyn’s Two Hundred Years Together (2002), Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century (2004), and Philip Mendes’s Jews and the Left (2014).

Chapter Four on “Neoconservatism as a Jewish Movement” is new to this edition, although its core has already appeared in the author’s previous book Cultural Insurrections (2007) and elsewhere. MacDonald’s account of how the neocons maintained a self-image as a beleaguered and embattled minority even as they determined the destiny of the world’s most powerful country is an impressive testament to the unchanging nature of the Jewish shtetl mindset.

Chapter Five on “Jewish Involvement in the Psychoanalytic Movement” has been expanded with material on Freud’s Hungarian-Jewish disciple Sándor Ferenczi and the Budapest school of psychoanalysis.

Chapter Six on “The Frankfurt School of Social Research and the Pathologization of Gentile Group Allegiances” includes new biographical sketches of the major figures and cites extensively from the recently published private correspondences of Horkheimer and Adorno. A new section on Samuel H. Flowerman (based on the research of Andrew Joyce) throws light on the nexus between the Frankfurt School and influential Jews in the communications media. There is also expanded coverage of Jaques Derrida and the Dada movement.

Chapter Eight on “Jewish Shaping of US Immigration Policy” has been updated and corroborated using more recent scholarship by Daniel Okrent Daniel Tichenor, and Otis Graham, as well as Harry Richardson and Frank Salter’s Anglophobia (2023) on Jewish pro-immigration activism in Australia. MacDonald makes clear that Jewish pro-immigration activism was motivated by fear of an anti-Jewish movement among a homogeneous White Christian society, as occurred in Germany from 1933–1945) Moreover:

Nevertheless, despite its clear importance to the activist Jewish community [and its eventual tranformative effects], the most prominent sponsors of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965,

did their best to downplay the law’s importance in public discourse. National policymakers were well aware that the general public was opposed to increases in either the volume or diversity of immigration to the United States. . . . [However,] in truth the policy departures of the mid-1960s dramatically recast immigration patterns and concomitantly the nation. Annual admissions increased sharply in the years after the law’s passage. (Daniel Tichenor, 2002, p. 218)

The Conclusion, “Whither Judaism and the West?” is heavily updated from the previous version. MacDonald speculates on the possible rise of a new non-Jewish elite that might challenge Jewish hegemony in three key areas: the media, political funding, and the academy. He sees Elon Musk, with his support for Donald Trump’s populism and (relatively) free speech, as a possible harbinger of such an elite. Musk has commented explicitly on Jewish hostility to Whites and taken heat for it.

Regarding the media, MacDonald writes:

If the 2024 election shows anything, it’s that the legacy mainstream media is distrusted more than ever and has been effectively replaced among wide swaths of voters, especially young voters, by alternative media, particularly podcasts and social media. […] The influence of the legacy media, a main power base of the mainstream liberal-left Jewish community, appears to be in terminal decline.

A recent sign of the times was the eviction of the New York Times, National Public Radio, NBC and Politico from their Pentagon offices to make room for outlets such as One America News Network and Breitbart.

Jewish financial clout is still in place, but may be of diminishing importance as well. As of August 2024, twenty-two of the twenty-six top donors to the Trump campaign were gentiles, and only one Jew—Miriam Adelson at $100 million—made the top ten. (Musk eventually contributed around $300 million. The author quotes a description of all the wealthy people in attendance at Trump’s second inaugural, and only one of the six men named was Jewish. MacDonald notes that “most of these tycoons were likely just trying to ingratiate themselves with the new administration, but this is a huge change from the 2017 and suggests that they are quite comfortable with at least some of the sea changes Trump is pursuing.”

The university is the most difficult pillar of Jewish power to challenge, as MacDonald notes, “because hiring is rigorously policed to make sure new faculty and administrators are on the left.” There has recently been a challenge to Jewish interests in the academy by students protesting—or attempting to protest—Israeli actions in the Gaza strip. But Ron Unz vividly describes what can happen to such students:

At UCLA an encampment of peaceful protestors was violently attacked and beaten by a mob of pro-Israel thugs having no university connection but armed with bars, clubs, and fireworks, resulting in some serious injuries. Police stood aside while UCLA students were attacked by outsiders, then arrested some 200 of the former. Most of these students were absolutely stunned. For decades, they had freely protested on a wide range of political causes without ever encountering a sliver of such vicious retaliation. Some student organizations were immediately banned and the future careers of the protestors were harshly threatened.

Protesting Israel is not treated like protesting “heteronormativity.” Two Ivy League presidents were quickly forced to resign for allowing students to express themselves.

Despite this awesome display of continuing Jewish power, anti-White “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion” policies are now under serious attack at American universities. MacDonald also notes that the academy is a less important a power base than either the media or political funding.

The Conclusion has also been updated with a consideration of whether multiculturalism may be backfiring on its Jewish creators as some members of the anti-White coalition turn to anti-Semitism.

It should be acknowledged that the insertion of new material into this updated edition required the deletion of a certain amount of the old. I was sorry to note, e.g., the removal of the table contrasting European and Jewish cultural forms, found on page xxxi of the second edition. So while everyone concerned with the question of Jewish influence should promptly procure this new third edition, I am not ready to part with my copy of the second.

Nathan Cofnas, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the

Nathan Cofnas, who bears an uncanny resemblance to the

To the extent that any ethnographic study of the Jews is less than hagiographic, one can be sure that the long knives will be sharped and the attack on the critic of the Jews writ large will be ruined. In this, I am reminded of Gilad Atzmon’s trenchant observation in his pithy book, The Wandering Who, that, “it is not the idea of being unethical that torments [the Jews] but the idea of being ‘caught out’ as such.” If one keeps this maxim in mind—indeed, if one amplifies this maxim—it serves as a hermeneutic principle to understand why Jews react the way they do to any form of group criticism. Every cognizable group of human beings, no matter the basis of their association, is not beyond group criticism except the Jews—and if there were ever needed a demonstration of the incredible power that Jews possess in Western societies, it is their repeated ability to marginalize and destroy anyone who criticizes the Jews as a group concerning supporting Israel (an apartheid state), questioning the various narratives of Jewish victimology, or offering a counter-narrative of collective Jewish misconduct and abuse of power. This power is amplified since they, the Jews, excoriate other groups as a matter of sport—it is not “group” analysis per se that is the problem, it is a less-than-flattering portrait of the Jews that is objectionable. Conveniently the weapon of choice is prophylactically to brand such opposition, “antisemitism,” and, in this, I am again reminded of Atzmon who noted that, “[w]hile in the past an ‘anti-Semite’ was someone who hates Jews, nowadays it is the other way around, an anti-Semite is someone that the Jews hate.” And there is no one that Jews hate more than someone who dares to critique the Jews as a group.

To the extent that any ethnographic study of the Jews is less than hagiographic, one can be sure that the long knives will be sharped and the attack on the critic of the Jews writ large will be ruined. In this, I am reminded of Gilad Atzmon’s trenchant observation in his pithy book, The Wandering Who, that, “it is not the idea of being unethical that torments [the Jews] but the idea of being ‘caught out’ as such.” If one keeps this maxim in mind—indeed, if one amplifies this maxim—it serves as a hermeneutic principle to understand why Jews react the way they do to any form of group criticism. Every cognizable group of human beings, no matter the basis of their association, is not beyond group criticism except the Jews—and if there were ever needed a demonstration of the incredible power that Jews possess in Western societies, it is their repeated ability to marginalize and destroy anyone who criticizes the Jews as a group concerning supporting Israel (an apartheid state), questioning the various narratives of Jewish victimology, or offering a counter-narrative of collective Jewish misconduct and abuse of power. This power is amplified since they, the Jews, excoriate other groups as a matter of sport—it is not “group” analysis per se that is the problem, it is a less-than-flattering portrait of the Jews that is objectionable. Conveniently the weapon of choice is prophylactically to brand such opposition, “antisemitism,” and, in this, I am again reminded of Atzmon who noted that, “[w]hile in the past an ‘anti-Semite’ was someone who hates Jews, nowadays it is the other way around, an anti-Semite is someone that the Jews hate.” And there is no one that Jews hate more than someone who dares to critique the Jews as a group.