Racial Politics in Latin America: What Race in Another America Tells Us About Our Destiny, Part 2

/15 Comments/in Featured Articles, White Racial Consciousness and Advocacy/by Patrick McDermottRacial Politics

What should we make of this history? Given a chance, the left did eventually rise to power as expected, riding a wave of support from impoverished Brown and Black voters in nations where Whites were usually a minority. But just a few years later, many of these same nations voted the left out of power again. How could this happen? Are race and demography less important than the Dissident Right imagines?

The answer is no, race matters enormously, but election results are the product of several different forces that are pushing in different directions simultaneously. The first of these is the one that is most apparent from this history — pendulum effects that swing elections back and forth depending on the public’s view of the government’s performance. In Latin America’s case, just about every government has struggled with persistent poverty, crime, and corruption, so these pendulum effects tend to work against whoever is in power. The effect is so strong that, unlike the United States, major political parties often come and go, exiting the stage once their brand has become too tarnished.

Beneath these pendulum swings, however, there are strong structural forces at work that continue from election to election. Race-based voting is one of the most important. A close examination of elections held across the region repeatedly shows that leftists rely heavily on support from Browner and Blacker voters who are usually poor, while conservatives rely heavily on Whites and Whiter mestizos (who are typically over half European genetically).

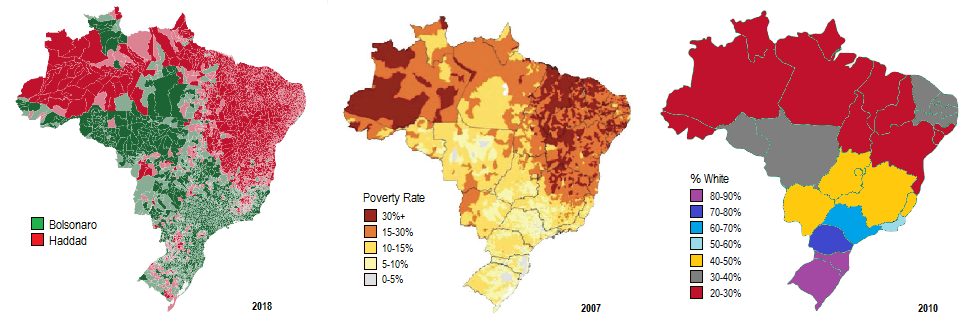

One illustrative example is the 2018 election of Jair Bolsonaro, the new right-wing Brazilian president dubbed the “Trump of the Tropics.” Bolsonaro drew his support from the Whiter southern part of the nation and the socially conservative rural heartland. His leftist opponent did better in the northeast, which is mostly Black and mulatto, and the northwest, which is substantially Indigenous. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Bolsonaro also did better among Whites who live closer to the crime-ridden areas of major cities and a bit worse among Whites who live further south, a safe distance from the mayhem.

These racial patterns repeat themselves throughout the region. Argentina’s conservative president Mauricio Macri won his 2015 election by winning the Whiter heart of Buenos Aires and most of Whiter central Argentina. The conservative Sebastián Piñera won in the Whiter parts of central Chile and Santiago. The conservative Iván Duque Márquez won in Colombia in the Whiter sections of Bogotá and the center of the country.

The leftist Nicolás Maduro won his last competitive election in Venezuela in 2013 in heavily Brown and Black areas of the country, while losing the Whiter areas of the east and west. The leftist Evo Morales consistently wins reelection in Bolivia with the support of his Indigenous base in the Western highlands.

The exception that proves the rule is Uruguay, the Whitest nation on the continent. It has continued to support the Broad Front, a leftist coalition that includes socialists and communists and touts legalized pot, abortion, and same-sex marriage among its policy achievements. Such leftist politics are typical of Whiter nations that have yet to experience the full benefits of diversity.

In most other Latin American nations, these racial voting patterns persist despite the presence of an important moderating influence — a large mixed-race population that seems resistant to explicitly race-based political appeals. Leftist academics bemoan this resistance, usually attributing it to a lack of social awareness and widespread acceptance of the theories of mestizaje and racial democracy, which argue that mixed-race societies do not suffer the same levels of racism and discrimination as other places like the United States.

Surveys of Latin America’s poor do not support this notion. Latin America’s mixed-race populations are well aware of existing racial disparities, they just do not strongly identify with them. This points to a different explanation that is less favored by leftists: genetic similarity theory, which says that people are more altruistic and less hostile to those who are genetically similar. This explanation is borne out by interviews with mixed-race voters.

“Do I value my Blackness? Of course! I take pride in it,” said one Brazilian mulatto in an interview. “But am I only Black? No! I also am descended from Indians and from Europeans. Should I disdain these heritages? Why shouldn’t I value all my heritages? Why should I pretend I only have one heritage when this is just not true?” Read more

Racial Politics in Latin America: What Race in Another America Tells Us About Our Destiny, Part 1

/10 Comments/in Featured Articles/by Patrick McDermott

Rio as seen by helicoptering elites.

Darkness fell over the São Paulo skyline. Like most cities, dusk brings the evening commute, but this one is a little different. One by one, all across the business district, helicopters lifted off buildings and roared into the humid night sky.

São Paulo has one of the largest private helicopter fleets in the world. Usually they are ferrying wealthy businessmen home, but sometimes a trip can include discreet female companionship and a hop to a nearby club. It has been this way for years. When the city still allowed electronic billboards, people said it reminded them of the movie Blade Runner.

“My favorite time to fly is at night, because the sensation is equaled only in movies or in dreams,” said one local businessman. “The lights are everywhere, as if I were flying within a Christmas tree.”

The view is nice, but the real reason is more prosaic. Like the future dystopia of Blade Runner, life is more dangerous on the ground. Criminals make a good living kidnapping business executives or members of their family. Fear has driven a similar business in bullet-proof cars.

The city is no less dangerous for the poor in the favelas, but their lives are worth a lot less. Some say that nearby Rio de Janeiro is using secret sniper teams to take out suspected criminals from afar. Anyone seen carrying a gun is a potential target — shoot to kill.

Such overwhelming disparities of wealth and poverty help define Rio and São Paulo, but it is not much different in the other mega cities like Lima, Buenos Aires, or Mexico City. This is the stark reality of Latin America, but it is also more than that. It is a window on America’s future. Read more

Inducing White Guilt

/51 Comments/in Evolutionary Psychology, Featured Articles, White Pathology/Guilt/by Andrew Joyce, Ph.D.“Group-based guilt is debilitating because it may undermine internal attributions for in-group success and may threaten the in-group’s identity as moral and good.”

Iyer et al. “White Guilt and Racial Compensation,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 2003.[1]

“We’re not sorry! And we’ve stepped over the prospect of being sorry.”

Jonathan Bowden

I am frequently bemused by the mystery of the failure of our ideas to win over those White masses sleepwalking into permanent displacement from their own lands. That which seems self-evident — the demographic projections, the crime figures, the well-documented plans and trends, the bold intentionality of it all — is yet insufficient to break through into the deeper instinctual consciousness. Why? In a recent conversion I had with Kevin MacDonald, it was mentioned that when White people are told they are being slowly replaced, they get angry. And yet it appears a gentle and transient anger, incapable of translation into clear political trajectories and easily muzzled by the poisonous triad of media, entrenched government, and the academy. My recent reading of Ed Dutton’s Race Differences in Ethnocentrism answered some questions, but provoked more. The text is primarily concerned with what might be termed “hard biological” explanations for low ethnocentrism among Europeans, possibly at the cost of placing too little emphasis on cultural and socio-ecological factors. In particular, I felt the text understated the case that present-day low ethnocentrism is something that has been deliberately cultivated over time, and that part of that cultivation has been the widespread dissemination of shaming propaganda carefully designed to threaten and undermine White in-group identity. I am thinking, of course, about the concept of White Guilt.

Discussions about White Guilt are becoming increasingly common on both the Left and Right, and basic distinctions can be made between explanatory theories. One set of theories ascribes to White Guilt a “dishonest and evasive” character, in which White Guilt is on some level a self-serving and self-satisfying charade that enables Whites to continue to patronise and dominate minorities. These theories emanate from the harder, old-school Marxist Left. Another set of theories ascribes to White Guilt an “honest and spontaneous,” character, in which it arises as genuine feelings of regret at alleged historical wrongs or at the holding of a privileged position in society. These theories emanate most commonly from the center-Left of the ideological spectrum. Another set of theories, ascribes to White Guilt an “honest but cultivated” character, in which White Guilt arises as genuine feelings of regret and discomfort at alleged past and present wrongs, and is the product of a debilitating and ceaseless social critique designed to undermine the ability of Whites to see their interests as legitimate and thus the ability to defend and protect those interests. These theories emanate almost exclusively from the dissident Right. The centre-Right appears to stand alone as advancing no position on the matter, much as it has forfeited taking any positions on mass migration or issues of ethnic identity. Read more

National Intelligence and its Consequences

/16 Comments/in Featured Articles, Race Differences in Behavior/by F. Roger Devlin, Ph.D.The Intelligence of Nations

Richard Lynn and David Becker

London: Ulster Institute for Social Research, 2019

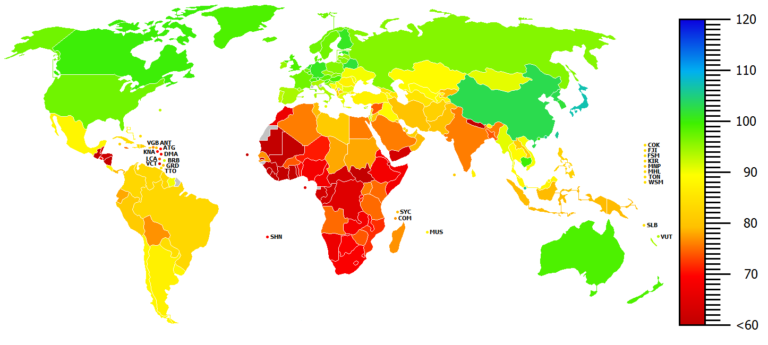

British psychologist Richard Lynn and Finnish political scientist Tatu Vanhanen published their first study of national IQ differences, Intelligence and the Wealth of Nations, in 2002. The book found that a nation’s average IQ correlated at .62 with its per capita income, meaning that IQ explained 38% of variation in wealth (0.38 = 0.62 squared). In addition to the expected opposition from egalitarians, some critics’ skepticism was aroused by shortcomings in the book’s empirical data: the authors had direct IQ measurements for only 81 countries; values for the other 104 were mere estimates based on neighboring countries.

British psychologist Richard Lynn and Finnish political scientist Tatu Vanhanen published their first study of national IQ differences, Intelligence and the Wealth of Nations, in 2002. The book found that a nation’s average IQ correlated at .62 with its per capita income, meaning that IQ explained 38% of variation in wealth (0.38 = 0.62 squared). In addition to the expected opposition from egalitarians, some critics’ skepticism was aroused by shortcomings in the book’s empirical data: the authors had direct IQ measurements for only 81 countries; values for the other 104 were mere estimates based on neighboring countries.

Plenty of international IQ data has accumulated since then, and the authors updated their results first in 2006 (IQ and Global Inequality), and again in 2012 (Intelligence: A Unifying Construct for the Social Sciences, hereafter Lynn & Vanhanen 2012; reviewed in TOQ 12:2, Summer 2012). In this last work, they provided direct data for 161 countries; the correlation between IQ and income rose to .71. Some of the earlier skeptics were won over.

Tatu Vanhanen died in 2015, but progress in the measurement of national IQ has continued. Heiner Rindermann of Chemnitz Technical University in Germany made an important contribution with his book Cognitive Capitalism: Human Capital and the Wellbeing of Nations (2018). Prof. Rindermann found a correlation of .82 between national IQ and per capita income, meaning that intelligence explains no less than two thirds of the variation between nations. He found positive correlations between IQ and many desirable social variables, boldly concluding that “national well-being mainly depends on the cognitive ability level of a society.” Rindermann also demonstrated that the cognitive ability of the most intelligent five percent of a population generally has a greater positive effect on national achievements and other desirable outcomes that the average intelligence of the overall population.

In this new book, Richard Lynn’s first since the loss of his Finnish coauthor, he teams up with David Becker, a younger colleague of Prof. Rindermann in Chemnitz. The authors explain:

The main difference between this study and the previously published studies is with regard to the level of detail provided. Previous studies have been criticised for drawing upon unrepresentative, small or incomparable samples with regard to particular nations. In updating these studies, we endeavour to obviate this problem, so that; this information is as clear as possible to other researchers. The central aim of this revision is to standardize each individual step of the process through which we have reached our estimations and made our calculations. This has the advantage of complete transparency, such that other researchers can refollow our steps should they wish to do.

This aim necessitates a highly technical presentation less adapted to the needs of the general reader than Lynn’s and Vanhanen’s books.

Also new to this study is use of the “National IQ Dataset,” a working file first uploaded to the internet in August, 2018 and continually updated to provide the best current data on IQ around the world. The most recent version can be viewed at http://viewoniq.org/.

The National Premise Revisited

/17 Comments/in Featured Articles, White Racial Consciousness and Advocacy/by Richard McCullochThis is a much shortened and slightly revised version of the author’s article “Visions of the Ethnostate” which was featured in the Fall 2018 issue of The Occidental Quarterly.

* * * *

It is an interesting fact that in the already vast and ever-growing corpus of works, books, essays, articles and videos addressing the racial problem by those who can be, and often are, denoted as “White advocates” there is a glaring lack of actual advocacy. Of the varied aspects of the racial problem, the more obvious ones, including their history and causes, are typically covered in great detail. The less obvious aspects, such as the long-term consequences of the racial problem, admittedly requiring some degree of projection and speculation, receive much less attention. Given the grim prospect of their continued racially destructive course, and the stark either-or choices they present, a reluctance to address or confront these consequences is understandable. To fully confront them, considering the full extent of their effects, would force one to face the logical and much more controversial next step of advocating or proposing possible alternative courses or solutions.

In The Dispossessed Majority in 1972 Wilmot Robertson set a new standard for describing the racial problem, but he didn’t propose a solution for it.1 He addressed this omission in his second book Ventilations in 1974, proposing a solution of territorial racial separation in which the far greater part of the United States would be kept together in what he called “The Utopian States of America,” with minorities concentrated in semi-autonomous enclaves under White hegemony.2 For example, Jews would be concentrated in enclaves in New York, Los Angeles, and Miami Beach. All Blacks outside the south would be concentrated in the twenty largest urban ghettos, which would be enlarged as needed for this purpose, while Blacks in the south would be concentrated in those counties where they were already the majority. The exceptions would be the Latinos who would be ceded a 40-mile deep band along the full length of the Mexican border, and the East Asians who would be given the Hawaiian Islands except for some US military bases.

Soon after reading Ventilations I met Jim Feller. He had also read Robertson’s books and showed me a partition map he had drawn up that was mostly based on Robertson’s proposal but with a different plan for Black separation, and apparently a much wider band for the Latino country than Robertson’s 40 miles. Less than two years later I saw Feller’s map again on the cover of the April 1976 issue of Instauration (Figure 1) illustrating an article by Robertson titled “The National Premise” that proposed a racial partition of the United States.3 With the exception of the change in the location of the Blacks, and making the minority states independent, it was close enough to Robertson’s earlier proposal that he was probably happy to adopt it.

Figure 1: Feller Partition Map

At the end of a sidebar explaining the map Robertson wrote:

If all this sounds impractical, we ask our readers to think of the alternatives. If the races are not separated soon, the Majority [Whites] will have to fight for survival or go completely under. Already we have lost many of our largest cities . . . and if things continue at their present pace, it is quite possible that we may soon be reduced to a formal and permanent state of serfdom. Separation and the surrender of a great deal of our land and property may well be our only means of survival.

That was 43 years ago. Since then we have witnessed the continuing “browning” of America, the ongoing dispossession and replacement of the White population by invasion-levels of non-White immigration, the more than doubling of the non-White (i.e., non-European) proportion of the population from 20% in 1976 to 41% in 2016, non-Whites becoming a majority of the population under the age of ten and projected to become an absolute majority around 2040, the rate of White reproductive intermixture with non-Whites doubling about every twenty years (e.g., per CDC figures, from 5.2% in 1990 to 11.6% in 2010), and cultural changes corresponding to the demographic changes. Read more

Review of Ed Dutton’s Race Differences in Ethnocentrism

/35 Comments/in Ethnic Genetic Interests, Evolutionary Psychology, Featured Articles/by Andrew Joyce, Ph.D. Race Differences in Ethnocentrism

Race Differences in Ethnocentrism

Edward Dutton

Arktos, 2019.

“Those who advocate Multiculturalism seem to have lost an important instinct towards group — and thus genetic — preservation. Once a society, as a whole, espouses Multiculturalism as a dominant ideology then the society is acting against its own genetic interests and will ultimately destroy itself.”

Ed Dutton

Watching his incredibly entertaining Jolly Heretic You Tube channel, it’s easy to forget that Ed Dutton is also an extremely serious, and increasingly prolific, researcher, author, and scientist. The recent publication by Arktos of Dutton’s Race Differences in Ethnocentrism follows closely in the wake of Dutton’s At Our Wits’ End: Why We’re Becoming Less Intelligent and What it Means for the Future (2018), How to Judge People by What They Look Like (2018), J. Phillipe Rushton: A Life History Perspective (2018), and The Silent Rape Epidemic: How The Finns Were Groomed to Love Their Abusers (2019). In Race Differences in Ethnocentrism, Dutton, who has collaborated with Richard Lynn on a number of occasions, builds impressively on the work of the latter and has offered, in this text, one of the most informative, formidable, pressing, intriguing, and poignant monographs I’ve read in years.

Dutton’s book is a work of science underscored by an inescapable sense of social and political urgency, and has been explicitly prompted into being by the need to address two questions “particularly salient during a period of mass migration”: ‘Why are some races more ethnocentric than others?’ and, most urgently of all, ‘Why are Europeans currently so low in ethnocentrism?’ In attempting to answer these questions, Dutton has designed a book that is accessible to readers possessing even the most modest scientific knowledge, without compromising on academic rigor or the use of necessary scientific language. The text is helpfully replete with explanatory commentary and useful rhetorical illustrations, and its opening four chapters are dedicated exclusively to placing the study in context and exploring the nature of the research itself. This is a book that can, and should, be read by everyone.

In the brief first chapter, Dutton explains ethnocentrism or group pride as taking two main forms. The first, positive ethnocentrism, involves “taking pride in your ethnic group or nation and being prepared to make sacrifices for the good of it.” Negative ethnocentrism, on the other hand, “refers to being prejudiced against and hostile to members of other ethnic groups.” Typically, a highly ethnocentric person or group will demonstrate both positive and negative ethnocentrism, although it is very common for people and groups to be high in one aspect of ethnocentrism but not in the other. It is also apparent that some countries and ethnic groups are very high in both forms of ethnocentrism while others are extremely low in the same. The author sets out to explore how and why such variations and differences have occurred, and are still fluctuating. This is clearly a piece of very novel research. Dutton remarks that “there exists no systematic attempt to understand why different ethnic groups may vary in the extent to which they are ethnocentric.” Dutton’s foundation is built on a deep reading of existing literature on the origins and nature of ethnocentrism, pioneered to some extent by R. A. LeVine and D. T. Campbell in the 1970s, and built upon most recently by Australia’s Boris Bizumic. These scholars advanced the argument that ethnocentrism was primarily the result of conflict. Another highly relevant theory in the study of ethnocentrism has been the concept of ‘inclusive fitness,’ which argues that ethnocentrism provides a method for indirectly passing on one’s genes.

Dutton closes his introductory chapter by providing an interesting overview of historical observations of differences in ethnocentrism. During the so-called ‘Age of Discovery,’ Europeans encountered large numbers of different and distant tribes, and many remarked on the reception they received from these groups. Some, such as the natives of Hawaii and the Inuit were noted as being extremely friendly, while the negrito tribes of the Andaman Islands, near India, remain notoriously hostile to outsiders, shoot arrows at passing aircraft, and kill intruding foreigners, including an American missionary in November 2018. The Japanese appear throughout history to have combined a moderate level of negative ethnocentrism with very high levels of positive ethnocentrism, resulting in a society typified by high levels of social harmony and in-group co-operation, and willing sacrifice for the nation in times of war. By contrast, the Yąnomamö tribe of Venezuela are very high in negative ethnocentrism but very low in positive ethnocentrism, resulting in a society riddled with lawlessness, extreme violence, poor social harmony, and an inability to form stable social structures of any kind. Differences in general levels of ethnocentrism are important because, as Dutton points out, those societies most welcoming of outsiders were subsequently colonized and fundamentally and permanently changed by migration. Meanwhile, those societies that displayed extreme hostility to outsiders have remained almost intact, and remain unchanged even centuries after the European ‘Age of Discovery.’ Read more