Jews and the Left by Philip Mendes: Review, Part 3

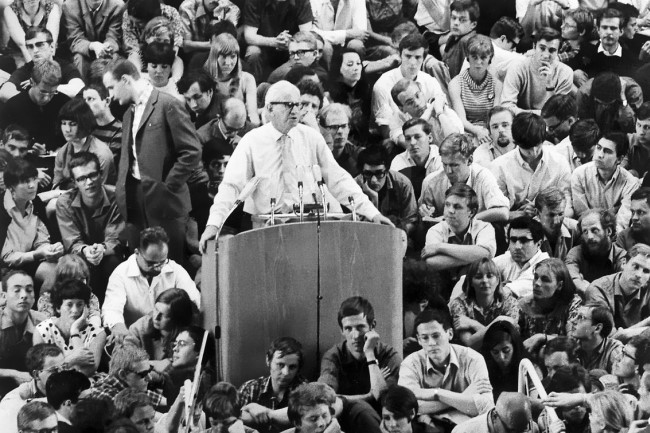

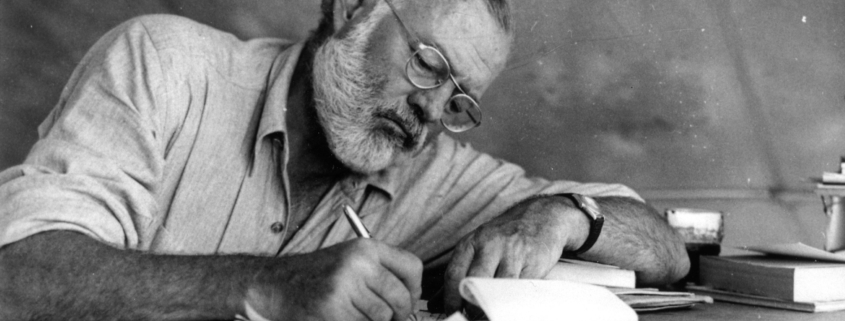

Herbert Marcuse addressing American students in 1968

Jewish involvement in the New Left

In Jews and the Left, Mendes recounts the disproportionate Jewish involvement in the New Left—a political movement that began in the early 1960s when students travelled to the southern states to support the emerging “civil rights” movement. In the mid-1960s, the movement switched to northern campuses to advocate student rights, free speech and opposition to the Vietnam War. This was the time when the ideas of Frankfurt School intellectuals like Erich Fromm and Herbert Marcuse began to displace orthodox Marxism in leftist movements throughout the West. Mendes notes that:

Jews contributed significantly to the theoretical underpinning of the New Left. From 30 to 50 per cent of the founders and editorial boards of such New Left journals as Studies on the Left, New University Thought, and Root and Branch (later Ramparts) were of Jewish origin. Radical academic bodies and think tanks such as the Caucus for a New Politics, the Union of Radical Political Economists and the Institute for Policy Studies were overwhelmingly Jewish. A number of the key intellectual gurus of the New Left such as Paul Goodman, Noam Chomsky, Howard Zinn, and Herbert Marcuse were also Jewish.[i]

The Jews who flooded the ranks of the New Left in the early-to-mid 1960s “appear to have been largely assimilated third-generation Jews from Old Left backgrounds [i.e., “red diaper babies”], although some had participated in Labor Zionist Groups.” Studies of American Jewish New Left activists reveal many had grown up in highly politicized left-wing family environments. Jews made up around two-thirds of the White Freedom Riders who went south in 1961, and about one-third to one-half of committed New Left activists in the USA, including key leaders such as Abbie Hoffmann and Jerry Rubin. In 1964 they represented from one-half to two-thirds of the volunteers who flooded Mississippi to help register black voters. At Berkeley in 1964, around one-third of the leaders of the Free Speech Movement (FSM) demonstrators were Jewish, as were over half of the movement’s steering committee, including Bettina Aptheker, Suzanne Goldberg, Steve Weisman, and Jack Weinberg who coined the famous phrase “You can’t trust anyone over thirty.[ii] Moreover:

In 1965 at the University of Chicago, 45 per cent of the protestors against the university’s collaboration with the Selective Service System were Jews. At Columbia University in 1968 one-third of the protestors were of Jewish origin, and three of the four student demonstrators killed at Kent State in 1970 were Jewish. Jews comprised a large proportion of the leaders and activists within Students for a Democratic Society (SDS). Some of the key leaders included the founder Al Haber, Todd Gitlin and Mark Rudd. Approximately 30 to 50 per cent of the SDS membership in the early–mid 1960s were Jewish.[iii] At one point in the late 1960s, SDS presidents on the campuses of Columbia University, University of California at Berkeley, University of Wisconsin (Madison), North Western University, and Michigan University were all Jews. Jewish participation in SDS was particularly high at Pennsylvania University and the State University of New York. There was also a number of Jews in the violent Weathermen group.[iv]

“Why not make the Jew a bounder in literature as well as in life? Do Jews always have to be so splendid in writing?”

“Why not make the Jew a bounder in literature as well as in life? Do Jews always have to be so splendid in writing?”