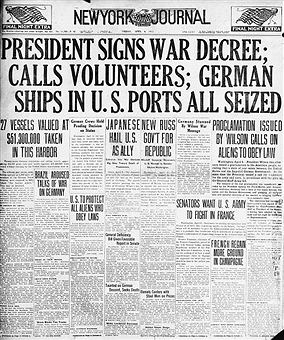

The War to End All Peace

/76 Comments/in Featured Articles/by F. Roger Devlin and Stephen J. Rosse

Today, 6 April 2017, marks the one hundredth anniversary of America’s entry into the First World War, probably the decisive factor in the eventual outcome of that war a year and a half later. Most schoolchildren, if they are taught anything at all about this event, hear it attributed to the German sinking of the Lusitania with American passengers aboard. Many do not know that the Lusitania was a British ship, that its sinking occurred nearly two years before our entry into the war, and that it was carrying a substantial amount of munitions, making it fair game under the laws of war. The existence of the munitions was only publicly acknowledged in 1982 after a salvage operation was announced; the British government finally admitted the truth, citing fear that explosives still inside the wreck might claim a few lives even yet.

Anti-German propaganda made much of the fact that the Lusitania was not a warship, but failed to mention that Britain had commonly disguised its warships to look like merchant ships and even to fly the flags of neutral nations. It was in response to such illegal practices that the German navy adopted a policy of treating any and all ships heading for Britain as potential enemy combatants. In the case of the Lusitania, the German Embassy in Washington even issued public warnings to potential travelers that if they sailed on any ships headed for Britain, they did so at their own risk.

Why the Syrian Gas Attack Is Probably Fake

/91 Comments/in Featured Articles/by Colin LiddellDirty tricks are like favourite records: play them too much and they get jaded. We haven’t heard about gas attacks in Syria for some time, but now, once again, the media — and, sadly, the Trump administration — is in overdrive about what is claimed to be a gas attack on the Syrian town of Khan Sheikoun by the Assad government.

First of all, the use of gas should not be regarded as particularly “evil” in a war that has also seen bombing and shelling of civilian areas as a matter of course, not to mention all the refinements to cruelty that ISIS and their like have introduced. But it is. We get it. Gas is “evil,” and you’re very, very bad if you use it. OK? So, stop!

But this means that gas attacks are also an extremely useful means of propaganda — but only if your opponents are seen to do them. In fact, this negative propaganda effect totally outweighs gas’s military benefits. And, yes, using gas may have military benefits, although in this case it’s hard to see how any possible benefits could outweigh the costs in terms of increasing the level of Western hostility.

An important precedent is the major gas attack, apparently by sarin rockets, that took place in the Damascus suburb of Ghouta in 2013 in which from between 350 and 1,400 people died.

Now, horrific as the attack was, there was a certain logic in it that made blaming the Syrian government plausible. The Syrian army was fighting street-to-street, house-to-house, trying to recapture urban territory, which any professional soldier can tell you is a nightmare for soldiers and civilian population alike. A way round this would be to use gas to clear out nests of entrenched opposition to make advances and pacification possible. Not ideal, obviously, but a way to break the deadlock and get a result. So, when the Ghouta attacks happened they at least made sense in a basic military tactical sense.

But any gains in this respect — and there weren’t many, as four years later Ghouta is still held by anti-Assad rebels — were soon outweighed by the negative international and diplomatic backlash, with the Obama and Cameron governments using the “propaganda” value of the attacks to push for military intervention. Read more

The Roman Variant of Indo-European Social Organization: Militarization, Aristocratic Government, and Openness to Conquered Peoples. Part 2

/14 Comments/in Featured Articles, Western Civilization, Western Culture/by Kevin MacDonald

Part 1 here.

The Openness of Roman Society: Social Mobility and Incorporating Different Peoples

Indo-European social structure was based on talent and ability.[1] Upward mobility was possible, and I-E groups in Europe tended to have only weak, permeable barriers between conquerors and conquered peoples — barriers that could be breached by the talented. This was also true on Rome. Social mobility was possible for the talented, and downward social mobility always a possibility:

From early times until la serrata del patriziato [the forming of an exclusive patriciate in the late fifth century BC], the Roman aristocracy was socially fluid and receptive to outsiders, including Latins, Sabines, and Etruscans” (163).

Support for this comes from the example of Appius Claudius who came to Rome from Sabine territory in 509 BC and became a member of the patriciate. Another example is L. Fulvius Curvus, from Tusculum, who became consul 60 years after Rome conquered Tusculum in 381 BC. Indeed, “The consular fasti of the early third century B.C. demonstrate the success of the Roman state in absorbing new elements from outside Rome into its aristocracy” (343). Consulships from 293–280 include 6 new clans, with 2 more by 264 BC; at least five of these were non-Roman in origin, the others Plebeian.

Another indication of openness is that the elites of conquered peoples were often allowed to retain their status:

Like other relatively flexible communities of central Tyrrhenian Italy, Roman society during the late seventh, sixth, and early fifth centuries B.C. is likely to have been open to horizontal social mobility [retaining a similar social status after being conquered by Rome (164)] and even to some degree of vertical social mobility. Consequently, the membership of the early senate is likely to have been characterized by a certain social fluidity. (109)

Thus rather than completely destroying the elites of conquered peoples, they were often absorbed within the Roman system, beginning with partial citizenship and ultimately with full citizenship rights. The result was to bind “the diverse Italian peoples into a single nation” (290). Whereas the Latin states were given complete citizenship, other areas were given citizenship sine suffragio, but they were forced to provide manpower for future wars, allowing Rome to continuously engage in warfare. If a person from these areas moved to Rome, he would receive full citizenship. New tribes were continually created from conquered groups, reaching 31 in 332 BC. Read more

The Roman Variant of Indo-European Social Organization: Militarization, Aristocratic Government, and Openness to Conquered Peoples. Part 1

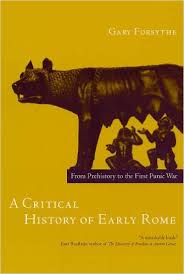

/10 Comments/in Featured Articles, Western Civilization, Western Culture/by Kevin MacDonaldA Critical History of Early Rome: From Prehistory to the First Punic War

Gary Forsythe

Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005

Gary Forsythe, associate professor of history at Texas Tech University, has written a critical history of the early Roman republic — critical in the sense that he casts grave doubts about a considerable amount of the received wisdom of the period. Nevertheless, the picture that remains provides a most welcome portrait of a critically important variant of the Indo-European legacy that is so central to understanding the West. The picture presented is of Rome of the republic as intensely militarized, with a non-despotic aristocratic government. Roman society during this period (509BC–264BC) permitted upward mobility and was open to incorporating recently conquered peoples into the system, with full citizenship rights. This openness continued into the later republic and the empire.

Gary Forsythe, associate professor of history at Texas Tech University, has written a critical history of the early Roman republic — critical in the sense that he casts grave doubts about a considerable amount of the received wisdom of the period. Nevertheless, the picture that remains provides a most welcome portrait of a critically important variant of the Indo-European legacy that is so central to understanding the West. The picture presented is of Rome of the republic as intensely militarized, with a non-despotic aristocratic government. Roman society during this period (509BC–264BC) permitted upward mobility and was open to incorporating recently conquered peoples into the system, with full citizenship rights. This openness continued into the later republic and the empire.

Indo-European Roots of Roman Civilization: The Military Ethos of Rome

Forsythe is well aware of the Indo-European roots of Roman culture. Essentially, the Mediterranean city-states established by I-E peoples were more settled, organized versions of basic I-E social organization based on mannerbunde. He describes “war bands” as common throughout the Greek, Roman, Celtic, and Germanic world, dedicated to raiding and fighting neighbors (i.e., the mannerbunde) (199). Leadership was based on military ability, followers sworn to fight to the death. In the early republic, aristocratic clans may well have been mannerbunde in the classic sense: the “current view,” which Forsythe is skeptical of, is that the battle of Cremera in 478 BC (a major Roman defeat at the hand of Veii, an Etruscan city, that occurred 30 years after the founding of the republic) was essentially undertaken by an aristocratic clan (the Fabians, who held consulships during the period) prior to the complete takeover by the state in organizing for war (200). In other words, at that time during the early republic, these clans operated with some independence from the Roman state.

Presumably reflecting this mannerbunde organization, patron-client relationships were very typical, with less wealthy people tied via reciprocal obligations to wealthy, powerful individuals. This is likely a holdover from Indo-European culture where war lords and their followers had mutual obligations. Forsythe notes that this mitigated social and economic disparities (216). One could be patron to another but also client to a wealthier individual. “Thus later Roman society was loosely bound together by a vast interlocking network of such relationships (216). Reflecting the non-despotic nature of Roman society (see below), patrons could be “accursed” for injustice against clients and thus either killed or ostracized.

A hallmark of Indo-European culture is that military glory is prized above all else. Thus Forsythe notes that around 311 BC, “Rome was a young and vigorous state headed by ambitious and energetic aristocrats, who were eager to utilize the state’s growing strength to enhance their own personal prestige and to further Rome’s influence and power” (307).

Various data … present the picture of a Roman aristocracy self-conscious of their power and that of the Roman state, ambitious for and reveling in military glory, and eager to advertise and catalogue their achievements for their contemporaries and posterity. … [Among aristocratic families, there was] a strong sense of family pride, tradition, and continuity. (340)

The Roman aristocracy was pervaded by a military ethos, according to which the greatest honor was won by victory in war, either by individual feats of valor or by commanding successful military operations. This ethos was not only maintained but even fueled by the competitive rivalry which characterized the Roman elite.. … Many of Rome’s Italian allies likewise possessed a well-established military tradition, so that the profitability of successful warfare (slaves and booty) bound the Roman elite, the Roman adult male population, and Rome’s allies together into a common interest in waging wars. The Roman state was therefore configured to pursue an aggressive foreign policy marked by calculated risk taking, opportunism, and military intervention. Consequently during republican times there were few years in which Roman curule magistrates were not leading armies and conducting military operations. (286).

Are Policies Promoted By Jewish Elites Really “Good For The Jews”?

/76 Comments/in Featured Articles/by Beau AlbrechtToday, Middle America is caught between the vice grips of plutocracy and crazy leftist policies. The two major parties offer us a choice between lukewarm neo-conservatism and cultural Marxist influenced liberalism, and neither cares about the common people. There’s plenty of blame to go around, though it’s well-documented here that a disproportionate amount of it is from the influence of Jewish elites. The details are indelicate but unmistakable.

Still, there’s a great difference between ordinary Jews and their elites. Most of the former are decent people, and most of the latter deserve to be deported and in many cases should be in prison for financial chicanery or treason. Do the policies of their elites really benefit the common Members of the Tribe? Since “Is it good for the Jews?” is the primary consideration, let’s see how well it’s been working out so far. First we’ll explore in a fictional example how that might work out for one of them.

David’s story

1979: David enters college, with ambitions to be a doctor. He also wants to start a large family some day. He soon finds that radical feminism is all the rage on campus. That began with the Second Wave harpies; a movement that just doesn’t know when to shut up. Thus, unpleasant attitudes are common. He supports feminism too – that’s just about equality, right? After David is shot down hard repeatedly, it leaves him terrified of asking anyone out. Eventually he gives up trying to find a girlfriend, reasoning that he’ll have more time to hit the books.

1990: Now a full-fledged doctor, he anticipates a pretty good cash flow. He looks for a house, but finds out there’s no way in hell he can afford one in Los Angeles, especially with the Federal Reserve’s prime rate at 10%. At least it’s not 20% like ten years ago! He gets an apartment in Watts instead. Being a socially conscious liberal, he considers it his life’s work to serve the underprivileged, and at least here he can be near his clientele. He figures he’ll fit right in; after all, as Franz Boas and Ashley Montagu revealed, race is only a social construct, right?

1991: Getting into business was more difficult than he expected. David still struggles with red tape, something with which he has little experience. Figuring out how to make a small business work turned out to be a daunting task. Although the government gives many advantages to big businesses, there’s not much to help a little guy starting out. Further, he’s paying off a whale of a student loan, as well as an exorbitant premium for malpractice insurance. He’s a very careful doctor, but malpractice insurance is a necessity because of all the bottom-feeder lawyers and their clients looking to win the lottery in court. He has to get credit cards to stay afloat, and soon he’s barely able to afford minimum payments. He begins to loathe bankers. He wonders, “If banking is supposedly a Jewish institution, like those anti-Semites say, then why am I getting screwed?” Read more

Born in Britain: Mass Immigration and the Twilight Zone

/44 Comments/in European Invasion, Featured Articles/by Tobias LangdonIf you think that the recent attack by a Black terrorist in London says anything about the harm done by mass immigration, then think again. A great liberal intellectual called Matthew D’Ancona has crushed such racist nonsense with these lines in the world’s greatest newspaper:

As we now know, the attacker, Khalid Masood, was British, born in Kent and brought up as Adrian Russell Elms. His story is one of radicalisation, the question being when and how he embraced extremist Islamist ideology: the path that led him to an act of murderous violence has nothing to do with immigration. (The Brexiteers’ immigration promises are unravelling fast, The Guardian, 27th March 2017)

“Nothing to do with immigration”: A Black terrorist

See? The terrorist was born here. He was 100% British. Immigration had nothing to do with his terrorism. Somehow the concept of second-generation immigrants is far too complex for these intellectuals, so that the ill effects of policies in place for 50+ years can only be discussed within the context of recent immigrants not born in the UK.

Voila! Crime, terrorism and academic failure by second-generation immigrants have nothing to do with immigration. Believing their own propaganda, these intellectuals imply that second-generation immigrants have been entirely shaped by mainstream British culture, so that the cultures immigrants bring with them to the UK are completely irrelevant. It’s the same with personal traits like IQ: Mental ability has nothing to do with the ethnic/racial/religious heritage of immigrants after the first generation. Whatever their performance, it is due to having been born in the UK, with low performance likely due to White racism. It’s like saying that Masood would have been born in the UK even if his parents had stayed overseas. Read more