Jewish–Hungarian Conflicts and Strategies in the Béla Kun Regime, a Review-Essay of “When Israel is King” (Part 5 of 5)

Go to Part 1.

Go to Part 2.

Go to Part 3.

Go to Part 4.

5118 words.

The casualty figures of dictatorships, political systems, or simply certain policies and views, play a significant role in historiography and mainstream political activism. There is a reason the mere lowering of the number of victims of what we know as the “Jewish Holocaust” is a crime in Hungary and many other countries. While the number of alleged or real victims of the Holocaust is protected by law, the questioning of Jewish responsibility is also “incitement against a community”—according to the Jewish Tett és Védelem Foundation (TEV), as already mentioned. While revisionism of any tragedy is academically legitimate, if the results of research give it foundation, we will see below that in the case of the victims and perpetrators of Bolshevism, a philosemitic slant dominates mainstream historiography.

Returning to the leitmotif of our study, in When Israel is King, the Tharaud brothers inevitably discuss the activities of the Lenin Boys. They mention that Bela Kun “sent [József Cserny] to Moscow to study terrorist organization. Cserny returned in a very short time, having been initiated in the right methods, and bringing with him eighty professional executioners for the further instruction of the Hungarians. A Russian Jew, Boris Grunblatt, and a Serbian burglar, Azeriovitch by name, were told off [sic] to recruit men for him in Budapest” (Tharauds, 2024, 123–124).

Regarding the number of victims of the red terror, publishing in the newspaper Népszava, Péter Csunderlik (2022) cites the official 1923 number of 590, which he claims is “relatively low compared to other countries” (note that we are talking about “only” 133 days), while also claiming that some of the victims were “killed in firefights or [were] common-law criminals executed for committing a crime,” revising the number to “380–365” (he adds that this might still seem high today, but “[i]n 1918–1920, the World War in Central and Eastern Europe was not essentially over yet”).

If they come for you and you let them kill you, this historian will generously consider you a victim—if you fight back, you are not even worth having your death be part of a list of martyrs. You are just a dead militant, apparently. Reasonably, dying while protecting yourself, your family and community, from illegally formed terror groups, would render one a victim—and a hero—but Csunderlik shrugs and lowers the number. That he accepts the claims of executions for crimes, made by a regime that sent terror groups to travel around the country, executing people based merely on suspicions, extrajudicially, might also raise concerns here about the author’s historiographical standards. We might wonder if Csunderlik would apply this kind of rigor to the number of victims of the so-called Jewish Holocaust’s official narrative (which, unlike our topic at hand, is actually protected from critique by law), and whether he would exclude large numbers of Jews from the list of those shot by, for instance, the Einsatzgruppen for partisan activities—or perhaps because they “did not have a Jewish identity” — as partisans, they were likely “internationalists,” after all.

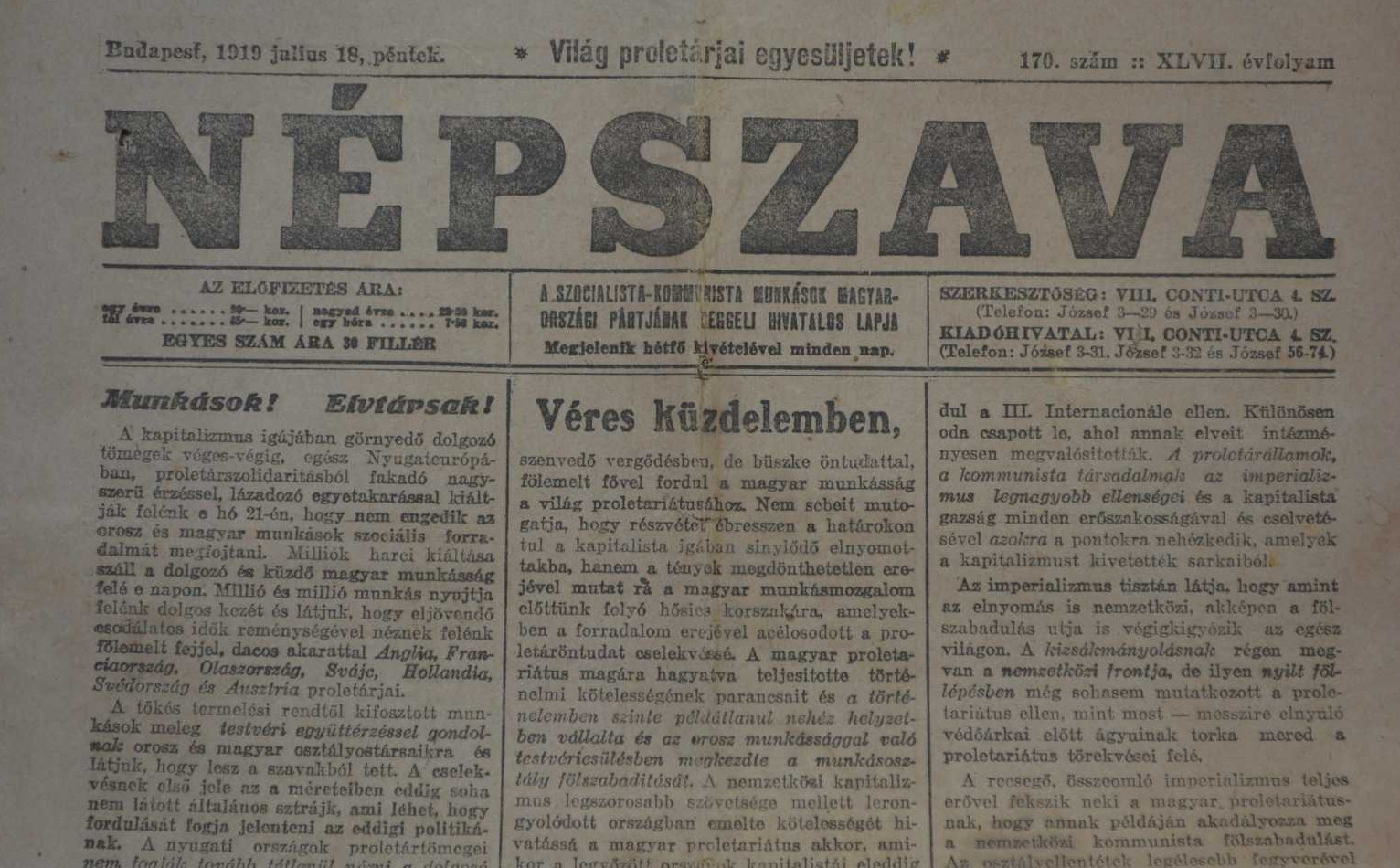

It is worth noting here that, although no longer published by Communists, Népszava back then was the newspaper that published, perhaps with the greatest delight, the writings of Bolshevik leaders of the Kun regime during their reign, along with other propaganda pieces.

A Népszava article glorifies the “heroic” Kun regime (July 18, 1919)

A Népszava article glorifies the “heroic” Kun regime (July 18, 1919)

Csunderlik (2023) does not only lower the “relatively low” number of victims—aside from denying the Jewish role—but is also in the habit of dismissing eyewitness reports with a mere wave of his hand—unlikely in the case of Jews claiming to be eyewitnesses to the Holocaust. In yet another piece regurgitating the exact same points we have already familiarized ourselves with earlier (sometimes for extended segments, word-for-word, with only minor additions), he accuses Cécile Tormay of spreading “lots of fake news, scare stories and untrue rumors” (ibid., 22, 23), and claims that her work is “full of verifiably fictional stories” (ibid.), without illustrating his claim with a single example, calling the book a “horror novel.”

As a Holocaust fact-checking revisionist myself, I am acutely aware of the tendency of emotionally involved—and perhaps traumatized—witnesses to be unreliable, and thus I apply that principle to Tormay’s work (or that of the Tharauds), as any reasonable person would. It is possible that some of the stories and details are inaccurate or untrue, and Tormay goes out of her way to underline that some of these things are things that she was told.

Csunderlik then mocks Tormay for thinking that the Galileo Circle was able to influence the war effort, leading to defeat, because of a segment of her book related to the Circle spreading anti-military flyers, calling it “laughable” that this could have had any influence (ignoring the fact that members of the movement were at the forefront of both the Aster Revolution and the Kun regime: their influence was significant). Csunderlik even fabricates a quote from her when he says that for Tormay “the domestic agents of the imagined ’Judeo-Bolshevik world-conspiracy’ were the atheist-materialist student association, the Galileo Circle, which produced anti-war pamphlets” (ibid.). Putting aside that the group did way more than just spreading flyers, nowhere in her work does the quoted text appear; it is presented as a direct quote in the Hungarian. But it is Csunderlik’s fixa idea to debunk this “world-conspiracy” theme by emphasizing how non-religious these Jews were, making anything “Judeo” self-evidently absurd in his presentation, attempting to keep Jewishness within a religious framework, conveniently—something we have already addressed. (That some members of the Circle, incidentally, literally worked with Soviet Bolshevik agents, making themselves “agents,” has also been shown earlier from Russian archival material.)

In Hungary “[p]ublic denial of the crimes of the National Socialist and Communist regimes” is a crime: according to the 1978. IV. law (modified in 2010): “Anyone who denies, doubts or trivializes the fact of genocide and other acts against humanity” in public, committed by these regimes, “commits a crime and is liable to up to three years’ imprisonment” (269/C. §). Note that this crime relates only to “the Holocaust”: if one publicly “violates the dignity of a Holocaust victim in public by denying, casting doubt on, or trivializing” the official story. Applying the extremely low standard for what counts as “Holocaust denial” in the country, Csunderlik might just be “trivializ[ing]” the Kun regime’s “acts against humanity” while violating the dignity of victims he doesn’t even consider victims. Of course, it is well-known that nobody actually gets in trouble in Hungary for trivializing or denying Communist crimes, nor for displaying their symbols publicly (NJSZ, 2023) — another supposedly illegal act (269/B. §). (On the anniversary of the Kun regime’s proclamation, a small group of Bolsheviks publicly commemorated the event, protected by police when a group of Nationalists showed up.)

Of course, the criminalization of research does not advance the truthful analysis of the past; the above is only to illustrate why the mainstream discourse still maintains that the Jewish role is taboo in such a biased system, since—if such regulation exists at all—instead of the author facing legal problems, Csunderlik’s article was funded with a grant from the state-funded Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Given that the young historian does not believe “that ’the truth’ of history can be known” because of the inherent biases of researchers (noting also that “if there is a ’truth’ at all, since postmodern historical theory denies it”), he has no reason to worry within a neoliberal, postmodernist establishment. With this attitude, his career will most likely continue to develop—something he surely knows already.

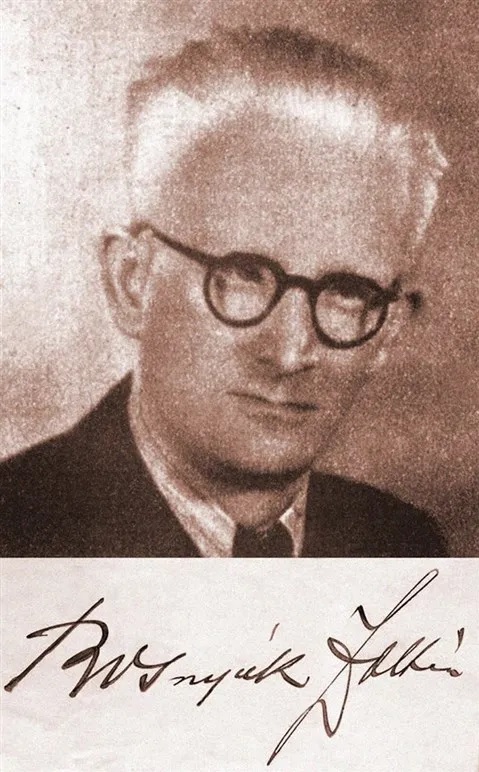

Péter Csunderlik (source: hirklikk.hu)

Péter Csunderlik (source: hirklikk.hu)

It can be added to the above, that according to Csunderlik, for example, we cannot even speak of a Hungarian nation from the period before the French Revolution (including the Árpád era), because modern nations were created only after the Revolution—which, in the light of the above, I believe, is a typical act of logical manipulation, and again, deriving from a predictable worldview. Of course, our ancestors are our ancestors, and how much we have to do with them is not changed by the French Revolution in any way. The understanding of nationhood does change somewhat over a thousand years, but our ancient codex-type gesta books, both the twelfth-century Gesta Hungarorum and Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum, emphasize the importance of common ancestry, which is the basis of the natio; i.e., the same stock of blood. These works are, in fact, national epics. (Hungarians are genetically related to their ancestors, see my earlier study introducing some of the genetic research on this topic: Csonthegyi, 2023). Gyula Kristó (1990, 430–431), a researcher of the Árpád-era Hungarians, states that “from the turn of the 11th–12th centuries onwards, the Hungarian [national] consciousness was—we can conclude with great certainty—established, based on the common (Hungarian) language and the tradition of common origin,” and then he mentions measures aimed at the protection of the “Hungarian” ethnic group, separate from others.

So we have learned from the above that the Jewish group is not a Jewish group because it is atheistic, and the history of Hungarians is not Hungarian because the modern concept of nation was developed at a later point in time. And if another interpretation becomes dominant next year, we may also learn that Hungarians were not Hungarians this year, either. Whether the historian will also explain to the Jews that they have nothing to do with their own past is unlikely—such semantic misrepresentation is presumably used for other purposes. According to Pew Research (2013, 54–55), for the vast majority of Jews today, “remembering the Holocaust is an essential part of what being Jewish means”—that is, modern Jewish identity is a post-Holocaust identity that Jews before the Holocaust could not have had: can we even talk about “Jewish” victims if the Jewish self-image today is somewhat different from that back then, following strictly Csunderlik’s logic? In any case, if this historian is in the habit of reducing victim numbers, and if atheism and internationalism, or the lack of professed Jewish identity, mean that a Jew is not a Jew, his task could be to subtract those from the magical “six million” number—based on the principles of ethics and logical consistency.

Victims and Perpetrators

In a desperate attempt to downplay the role of the Jews, Géza Komoróczy also manipulates the data in the usual, infantile way (e.g., Jewish Communists were not Jews because they were Communists, etc.); for example, he emphatically notes that the “not (!) Jewish” József Cserny was the commander of the Lenin Boys (Komoróczy, 2012, 361), presumably because of his Hungarian origin, so apparently no sealed and notarized proof stating ethnic identity is required, and mere origin is sufficient to classify persons as part of ethnic groups—unless the Jewishness of Jews is to be obfuscated.

Komoróczy (2012, 363) then attempts to emphasize Jewish victimhood, by presenting two sets of data: the first set is the more well-known 590 number, of which 44 are considered Jewish; the second set is the number 626, of which 32 were supposedly Jewish. Additionally, he mentions a monument, erected in 1936 on Kossuth Square (Budapest), and the 497 names featured on it, of which 32 are Jewish. If we take the data presented by this philosemitic, Hebraist author as our foundation, then the Jewish victims of the Bolsheviks can be concluded as being 7.4 percent, 5.1 percent, and 6.4 percent, respectively. This is proportionate to their share in society at the time; as is known, in 1910, Jews constituted 5 percent of the total population. However, since Jews had a heavy overrepresentation among the bourgeoisie, the researcher would expect that a dictatorship of the proletariat would produce more victims from this demographic. But according to this, that was not the case (instead, the regime primarily targeted poor rural Hungarians). In contrast to this, for the dictatorship itself, Jews were overwhelmingly responsible, thus, downplaying their role by pointing the finger at their victims, is a rather shameful tactic.

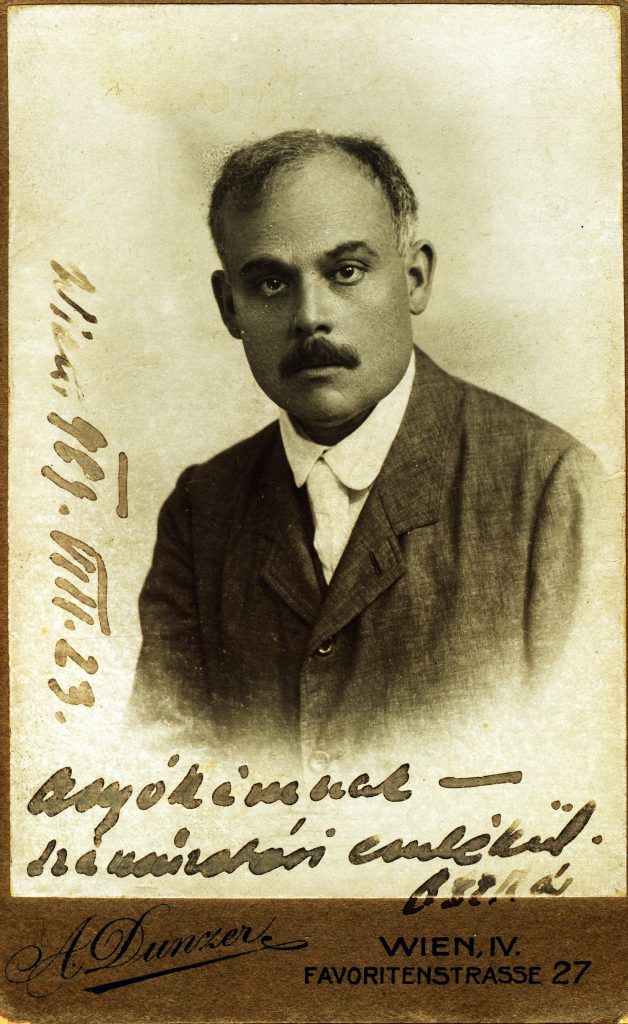

In his thorough study on Jews in Hungary—their numbers, influence, and prospects—Zoltán Bosnyák (1905–1952), one of the most prominent scholars of the Jewish question at the time, presented demographic data in general, but also of only “Torn-Hungary” (Csonka-Magyarország, i.e., present-day Hungary, after territorial losses) where Jews consisted 6.2 percent of the population in 1910 (Bosnyák, 1937, 10). The Kun regime mainly focused on this territory, making this number the most relevant for us. His data on the “upper ten thousand,” which is to say, in contemporary language, “the 1%” of society (supposedly the main enemy of the “proletarian” dictatorship) is heavily Jewish. In Bosnyák’s estimation “[o]ne third of the top ten thousand are Jews (plutocracy), the second third are related to Jews by blood (aristocracy), and the last third are pro-Jewish because they are dependent on and indebted to Jews (intellectual aristocracy)” (ibid., 80). According to this, we see again, that Jews were proportionately represented among the victims—until we take their share in the upper classes into account, which will render this proportion actually underrepresented. Bosnyák concluded that “one of the most important prerequisites for the final solution of the Jewish Question is the formation of a new, self-confident, racially conscious, Jew-free, leadership-oriented Hungarian middle and upper class” (ibid.). It is deeply tragic that the same Jewry, whose acquisition of power Bosnyák so passionately warned about, returned to power after 1945—and this Jewry sentenced him to death for that very warning. He was executed on October 4, 1952, by the newer Jewish dictatorship of Rákosi-Rosenfeld Mátyás, Farkas-Lőwy Mihály, Gerő-Singer Ernő, Révai-Lederer József, and their associates…

Zoltán Bosnyák

Zoltán Bosnyák

If we look at data about the Lenin Boys, we find what we could predict at this point: according to the research of historian Gergely Bödők (2018, 134): “Catholics, approaching 58 percent, are close to the national average (67 percent) for the whole population, making them the largest religious group. In ’second place,’ the Jewish denomination accounted for 21 percent, while 5–6 percent of the total population, and among the ’Lenin Boys’ they were nearly four times as much, making them the most over-represented. However, this is still far below the proportion of People’s Commissars of Jewish origin, which is estimated at 60–70%.” This tells us that Catholics were underrepresented (his Table 1 actually says 57 percent, not 58), but compared to victims, Jews were at least four times as likely to be the murderers, and 12–14 times as likely to be Commissars who were running the regime (not to mention that the Lenin Boys were commanded exclusively by Jews, as noted above). There were also 13 percent Reformed, 4 percent Evangelicals, 3 percent Greek Catholics, and 1 percent Orthodox and Unitarians, respectively, while 129 had no religion registered. This is only based on religious data, however, which is not the best, considering how, generally speaking, these young men tended to be atheists, and we must also remember that many Jews officially converted to Christianity in those decades, which helped them with social mobility. In other words, the ratio is likely higher still.

A well-known symbol of the so-called Jewish Holocaust in Hungary is the monument “Shoes on the Danube Bank,” and the story of the “Danube shootings.” It is less well-known that the method of execution using the Danube was first used by the Lenin Boys. The Tharaud brothers also describe the story of Sándor Hollán (1846–1919) and his son, Sándor Hollán, Jr. (1873–1919):

1. Hollan and his son, the one a former undersecretary for state, the other a railway director, were denounced by their concierge as being suspected of anti-Bolshevist tendencies, and their names appeared on the list of hostages drawn up by the sinister Otto Klein-Corvin. One night a motor lorry, driven by Red Guards, drew up at their door. “I am going to make it hot for these two,” declared a certain Andre Lazar, who was directing the expedition, and for whom the elder Hollan had once refused to sign a request asking that he should be dispensed from military service. The terrorists went into the Hollans’ house, arrested them, and forced them into the motor. (Tharauds, 2024, 126).

Then they were taken to the Széchenyi Chain Bridge, where they were shot from the back, into the Danube, or at least shot and then their bodies were thrown into it by the red terrorists. (There is no information on whether they resisted, so even Csunderlik-types are forced to count them among the victims.)

The sentencing and execution of József Papp by the Lenin Boys in Sátoraljaújhely (a city in the North-East of Hungary), April 22, 1919 (Hungarian National Museum)

The sentencing and execution of József Papp by the Lenin Boys in Sátoraljaújhely (a city in the North-East of Hungary), April 22, 1919 (Hungarian National Museum)

Blinkens, Böhm, and the Bolsheviks

The narratives outlined earlier are, of course, propagated by the Open Society Archive (OSA), part of the Jewish George Soros-affiliated Central European University, which has been renamed the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archive after a major donation—the donors here being the father (and his wife, both Jewish), of US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken. According to the OSA, the over-representation of Jews can also be explained by the fact that at the time there was a “rigid political system that effectively excluded them from the political sphere,” so Jews were attracted to a new system (which is itself a Jewish motivation, but this may not be obvious to the OSA). The concept of Judeo-Bolshevism is sought to be debunked by claiming that the system had Jewish victims (just as German National Socialists had German victims, yet no one disputes that they were driven by German interests and identity), and by arguing that there were patriots among the Jews who, for example, opposed the loss of territories. They mention Vilmos Böhm, the Berinkey government’s Minister of War, as an example of this, but fail to add that Böhm, among others, was one of the facilitators of the Bolshevik takeover by collaborating with them, and he later became commander-in-chief of the Red Army. In this role, to portray him as patriotic, while part of the Bolshevik transformation of the country, is disgraceful.

As far as Böhm’s seemingly patriotic statements are concerned, it is worth recalling that in his 1923 book Két forradalom tüzében (In the Fire of Two Revolutions) he clearly states how the new regime feared the thousands of Szekler (Transylvanian Hungarian) troops, and therefore, instead of accepting losses of territory, they wanted to push the Hungarians closer to the Soviets, by agitating against the Western powers. After realizing that “the adoption of the [Vix] Note will create a storm in the country which will destroy any government which complies with the demands of the Note,” they decided that “the whole country must be called to armed defense, the Western orientation must be replaced by an Eastern orientation towards Russia,” and the Social Democrats “must agree with the Communist Party to establish an alliance with the Russian Soviet troops on the northern border of old Austria” (Böhm, 1923, 240–241, emphasis in the original).

As the reports made it clear that “the Szekler troops and officers would not leave their positions without a fight under any circumstances, would not retreat” (ibid.), Böhm says: “We had to take into consideration the mood and determination of these troops. If the government, without consulting them, simply orders them back from the frontier, thus sealing their fate and foregoing the possibility of liberating their country, in that case, this desperate armed force, under the influence of nationalist agitation, will undoubtedly turn against the government and the revolution, and its victory will lead to the victory of a bloody counter-revolution.” (Ibid.) Böhm’s Hungarian Wikipedia article even quotes from his patriotic speech to the Szeklers, but the above motivation is not explained there either. It is also noted in the article that “from the excessive pacifism of the Aster Revolution, by March 1919, he had come to the idea of armed defense of the homeland”—in words, at least, but then he handed the levers of power over to the Bolsheviks only days later, and instead of protecting the borders of the homeland, he turned the armed forces—under the red flag this time—against Hungarians themselves. Nevertheless, he is the positive example of Jewish patriotism in the Jewish Blinken OSA Archive.

As for the so-called northern campaign, it was also aimed at spreading Bolshevism, rather than regaining territory, which soon became clear indeed. As a result, the soldiers’ enthusiasm waned, and the forces collapsed—the Slovak Soviet Republic did not even last a month. The Jewish Zoltán Szántó, regimental commander of the Red Army, in his article The Role of the 1st International Red Army Regiment in the Northern Campaign, describes the titular event as “the sacrifice made by internationalists for the survival of Hungarian Soviet power…”—so not for territorial defense (quoted in Chishova & Józsa, 1973, 274).

Counter-Revolution and Red Collapse

While we are on the subject of victims, it is worth pointing out that the Hungarians did not just passively tolerate the Bolshevik terror but resisted it time and again. Relevant literature is the book of Lénárd Endre Magyar (2020) on the history of the counter-revolutionary events in Szentendre and the collection of notes by Pál Prónay’s (1963)—perhaps the most prominent counter-revolutionary. When Bolshevik power collapsed with the advance of the Romanian troops, this counter-revolutionary momentum was no longer contained by the hordes of Lenin Boys. This is how Lajos Marschalkó recalled the mobilization of the Hungarian resistance:

By the time the train of the People’s Commissars, loaded with treasures, left Hungary, the nucleus of the Hungarian National Army, which had been formed in Szeged under French occupation, mainly through the organizational work of Captain General Gyula Gömbös, was ready three months earlier to call Rear Admiral Miklós Horthy to lead it. When he arrives in Szeged at the end of April 1919, Gyula Gömbös prophesies of a new world. (Marschalkó, 1975, 193)

According to the Tharauds (2024, 154), Béla Kun “also firmly believed that a general revolution would break out simultaneously on the same day, July 20th, in Germany, England, Italy, and France. So he chose that date to launch his offensive. But that catastrophic day, July 20th, 1919, was a most peaceable one throughout Europe. The world revolution in which Bela Kun believed as naively as Karolyi had done a short time before did not take place. And to crown his humiliation he was very soon made to realize that his soldiers were useless.” Some of the leaders then fled to Russia, others, like Ottó Korvin, were captured and executed, while Tibor Szamuely did not wait his turn: he committed suicide at the Austrian border. As Dávid Ligeti (2019, 35) reminds us, “[t]he majority of politicians who then lived in the Soviet Union in the 1930s were victims of Stalinist purges, i.e. they were executed on the orders of the Bolshevik dictator—besides Béla Kun, we can also mention the cases of József Pogány and Béla Vágó.”

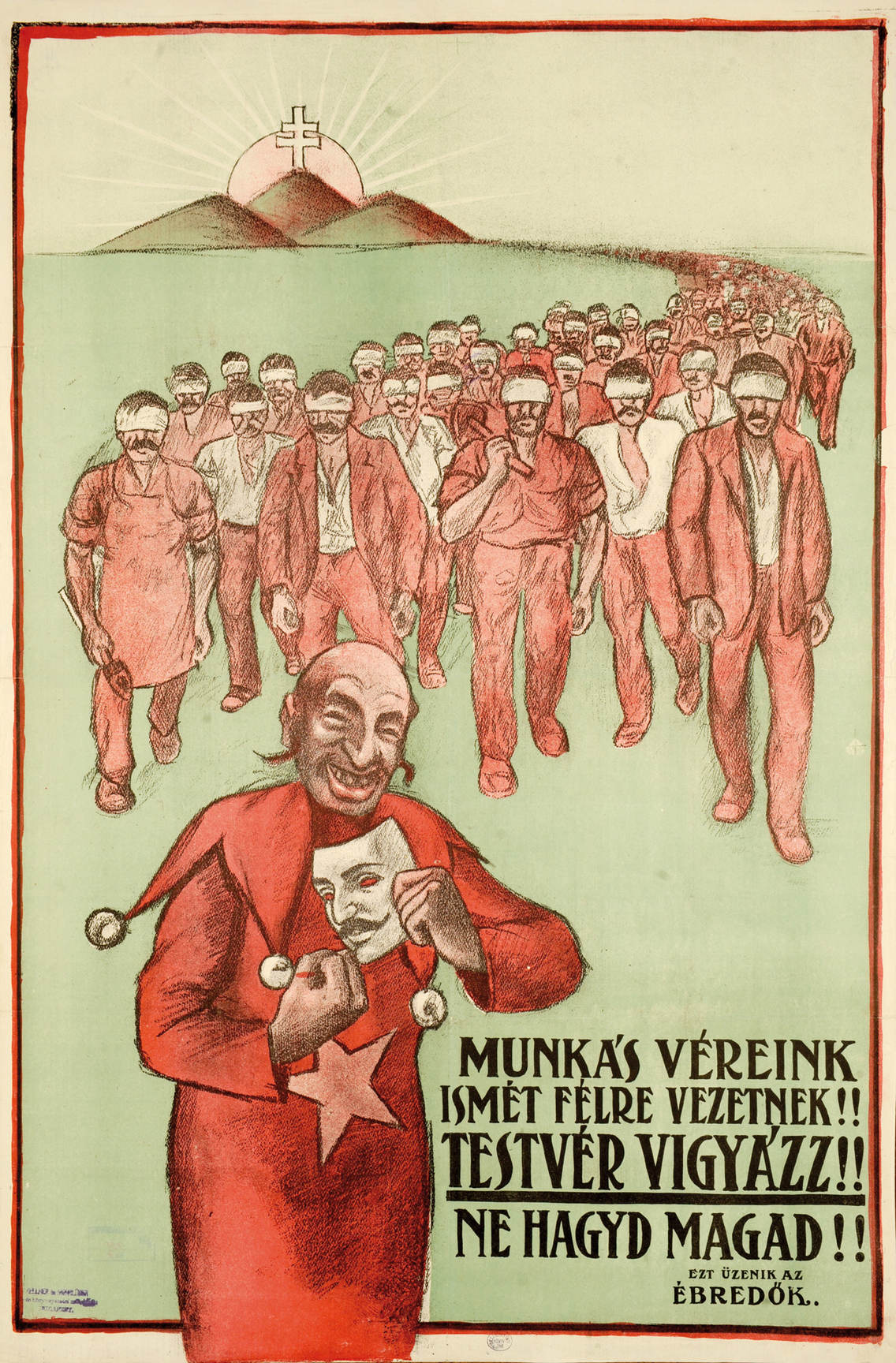

“Our worker brothers, you are being deceived again!! Watch out, brother!! Don’t let them!!”—poster of the Awakening Hungarians (Ébredő Magyarok) group warning after the fall of the Kun regime that Jewish influence did not disappear

“Our worker brothers, you are being deceived again!! Watch out, brother!! Don’t let them!!”—poster of the Awakening Hungarians (Ébredő Magyarok) group warning after the fall of the Kun regime that Jewish influence did not disappear

Towards the end of their work as chroniclers, the Tharaud brothers sum up the depressing mood after the storm, with poignant sympathy:

These brutal scenes no longer take place today, but the Jewish question remains. All Hungary has risen up to suppress the Jews. They wish to expel the five hundred thousand Galician Jews who arrived in the country during the war. The number of Jews admitted to the university has been limited so as to diminish their position in the liberal professions; the Masonic lodges, which had become almost completely Jewish, have been closed; everywhere Christian banks and cooperative societies are being established to replace the Hebrew middleman. Publishing houses and newspapers are being created whose mission it is to defend the national intellectuality. A violent struggle has been entered upon between two spirits and two races. (Tharauds, 2024, 160)

It was treachery, or—if we insist on being polite—a mistake on the part of those who were responsible for the Hungarian nation in the decades, or rather, centuries, preceding all this, to allow this group conflict to reach this point. The new Hungarian State of 1849, which had already planned the emancipation of the Jews, and the disastrous emancipation of 1867—the law, which was introduced by Prime Minister Gyula Andrássy (1823–1890) and was widely accepted by both the House of Representatives and the House of Lords—had already set the stage. There could be no excuse for not foreseeing where all this would lead—Győző Istóczy saw it clearly, as did those who helped him into Parliament, to represent this growing concern. The evisceration of rural Hungarians, the cultural and intellectual corrosion, and then the bloody mass murders, were all attributable to this—but only after a lost war, to be followed by yet another Jewish regime, from which Hungarians rebelled against again in 1956, for a few days at least. And the cycle continues to this day, with taxpayer-funded sectarian Jews filing criminal reports on Hungarians, for daring to ask for self-reflection over their past sins, or forcing Hungarians into hiding under pseudonyms in their own homeland, if they dare to question their mythical role as victims—since only Jews can be victims in this dynamic, and the perpetrators are Hungarians whose “identity” no philosemite sets extreme standards for by saying thay they don’t know whether Hungarians are Hungarians just because they were born one. If these ancestors had no excuse a century and a half ago, we really have none at all today. Istóczy tried to spur his compatriots to action just a decade before the Jewish terror:

And let those who can, do something for the cause, if for no other reason, then because we, the present generation, will somehow manage to get along with the issue as long as we live; but what fate awaits our children and grandchildren if things continue to go on as they have been going on, is another matter. (Istóczy, 1906, 20.)

It would, therefore, be worth listening to those, who foresaw where things were going: the Istóczys, the Bosnyáks, the Tormays, the Marschalkós, and many other truth-telling Hungarians who feared for their nation—or Frenchmen, like the Tharaud brothers, in this case. It’s been going on for thousands of years, time to draw the obvious conclusion, pleasant or not. The work of the French brothers is an old-new addition to this process.

Bibliography

Bosnyák Zoltán. Magyarország elzsidósodása. Budapest, 1937.

Bödők Gergely. Vörös- és fehérterror Magyarországon (1919–1921). Doktori értekezés, Eszterházy Károly Egyetem. Eger, 2018.

Böhm Vilmos. Két forradalom tüzében: Októberi forradalom, proletárdiktatúra, ellenforradalom. Munich: Verlag für Kulturpolitik, 1923.

Chishova, Lyudmila; Józsa Antal (eds.). Orosz internacionalisták a magyar Tanácsköztársaságért. Budapest: Kossuth Könyvkiadó, 1973.

Csonthegyi Szilárd. Konzervatív nemzetárulás a „vendégmunkás” migránsbetelepítés fényében (III. rész): genetikai érdekeink számokban. [Conservative Treason of the Nation in the Light of “Guestworker” Resettlement (Part 3): Our Genetic Interests in Numbers.] Kuruc.info, August 26, 2023. https://kuruc.info/r/9/263576/ (Accessed April 10, 2024)

Csunderlik Péter. A 133 napos „vörös farsang” – Mi volt a Tanácsköztársaság? Népszava, 2022. március 27.

Csunderlik Péter. “A Tanácsköztársaság és a »judeobolsevik összeesküvés« mítosza.” BBC History: A Világtörténelmi Magazin 2023.10 (2023): 19–23.

Donáth Péter. A Cserny-különítmény rémtettei „Mozdony-utcai laktanyájukban” 1919 júliusában. Fery Oszkár és tiszttársai halálának körülményei, következményei, utóélete. Donáth Péter szerk.: Sorsfordító mozzanatok a magyarországi kisgyermekkori nevelőképzés, a Budapesti Tanítóképző Főiskola, az ELTE TÓK és épülete történetéből. Budapest, Trezor Kiadó (2012): 144–254.

Istóczy Győző. A magyar antiszemitapárt megsemmisitése s ennek következményei. 2. bőv. kiad. Budapest, 1906.

Jérôme Tharaud, Jean Tharaud. When Israel is King. Antelope Hill Publishing, 2024.

Komoróczy Géza. A zsidók története Magyarországon. II. 1849-től a jelenkorig. Pozsony: Kalligram, 2012.

Konok Péter. “Az erőszak kérdései 1919–1920-ban. Vörösterror–fehérterror.” Múltunk – Politikatörténeti Folyóirat 55.3 (2010): 72–91.

Kristó Gyula. “Magyar öntudat és idegenellenesség az Árpád-kori Magyarországon. L’idée de la Pureté et de L’antagonisme Ethniques dans la Mentalité Hongroise Médiévale.” Irodalomtörténeti Közlemények. A magyar tudományos akadémia irodalomtudományi intézetének folyóirata 94.4 (1990): 425–443.

Ligeti Dávid. “Hazánk első totális diktatúrája: a Tanácsköztársaság a centenárium fényében.” Somogy 47.2 (2019): 30–35.

Magyar Endre Lénárd. „A rémuralom készséges szolgája kívánt lenni”? Perjessy Sándor és a Tanácsköztársaság elleni felkelés Szentendrén (1919. június 24–25.). Budapest, Clio Intézet, 2020.

Marschalkó Lajos. Országhódítók. Munich: Mikes Kelemen Kör, 1975.

NJSZ: Határozott, kettős mércétől mentes és törvényes rendőri fellépést az 1945-ös budavári kitörésre megemlékezőkre támadó vörös csillagos, egyre agresszívabb antifák ellen! Nemzeti Jogvédő Szolgálat közleménye, 2023. február 11., www.njsz.hu.

Pew Research Center. “A portrait of Jewish Americans: Findings from a Pew Research Center Survey of U.S. Jews.” Washington, DC: Pew Research Center (2013).

Prónay Pál; Szabó Ágnes, Pamlényi Ervin (eds.). “A határban a halál kaszál: fejezetek Prónay Pál feljegyzéseiből.” Budapest: Kossuth, 1963.

Werth, N. (1999). “A State against Its People: Violence, Repression, and Terror in the Soviet Union.” In Courtois, S., Werth, N., Panné, J., Paczkowski, A., Bartosek K., & Margolin, J. (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, trans. J. Murphy & M. Kramer. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Wolin, S., & Slusser, R. M. (1957). The Soviet Secret Police. New York: Praeger.

Oszkár Jászi (source: szevi.hu)

Oszkár Jászi (source: szevi.hu) Some members of Po’alei Zion in Łowicz, 1917

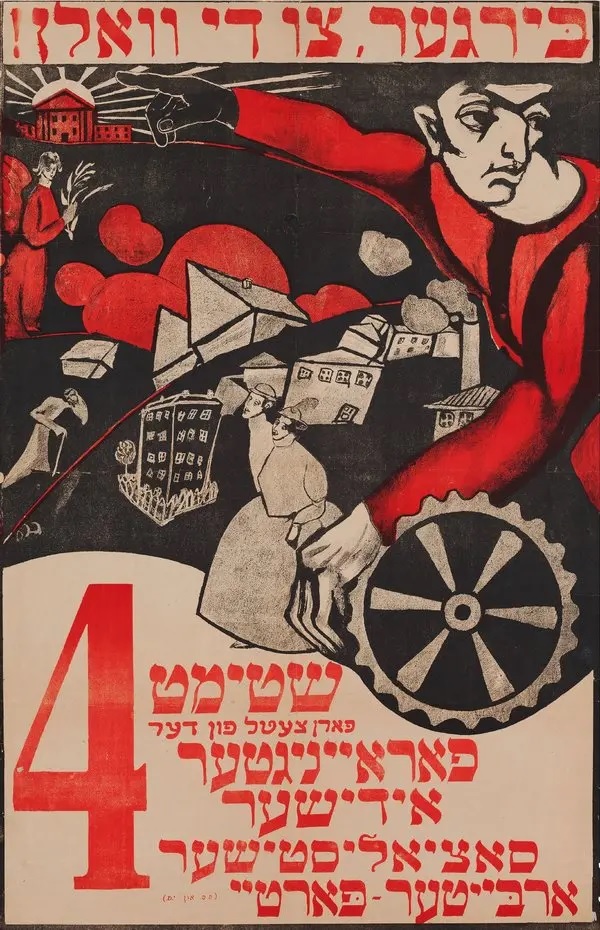

Some members of Po’alei Zion in Łowicz, 1917 “Vote for the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party” – Ukrainian election poster in Yiddish from 1917 (Ne Boltai Collection)

“Vote for the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party” – Ukrainian election poster in Yiddish from 1917 (Ne Boltai Collection)

Bjöeb Hoecke (center)

Bjöeb Hoecke (center) Béla Kun (front) with Tibor Szamuely (back, left)

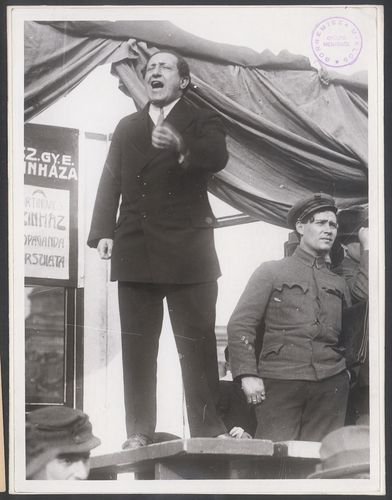

Béla Kun (front) with Tibor Szamuely (back, left) József Pogány-Schwartz, People’s Commissar, speaks at a recruitment meeting in Heroes’ Square, April 6, 1919.

József Pogány-Schwartz, People’s Commissar, speaks at a recruitment meeting in Heroes’ Square, April 6, 1919. Celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Bund in Warsaw, 1927 (source: yivoarchives.org)

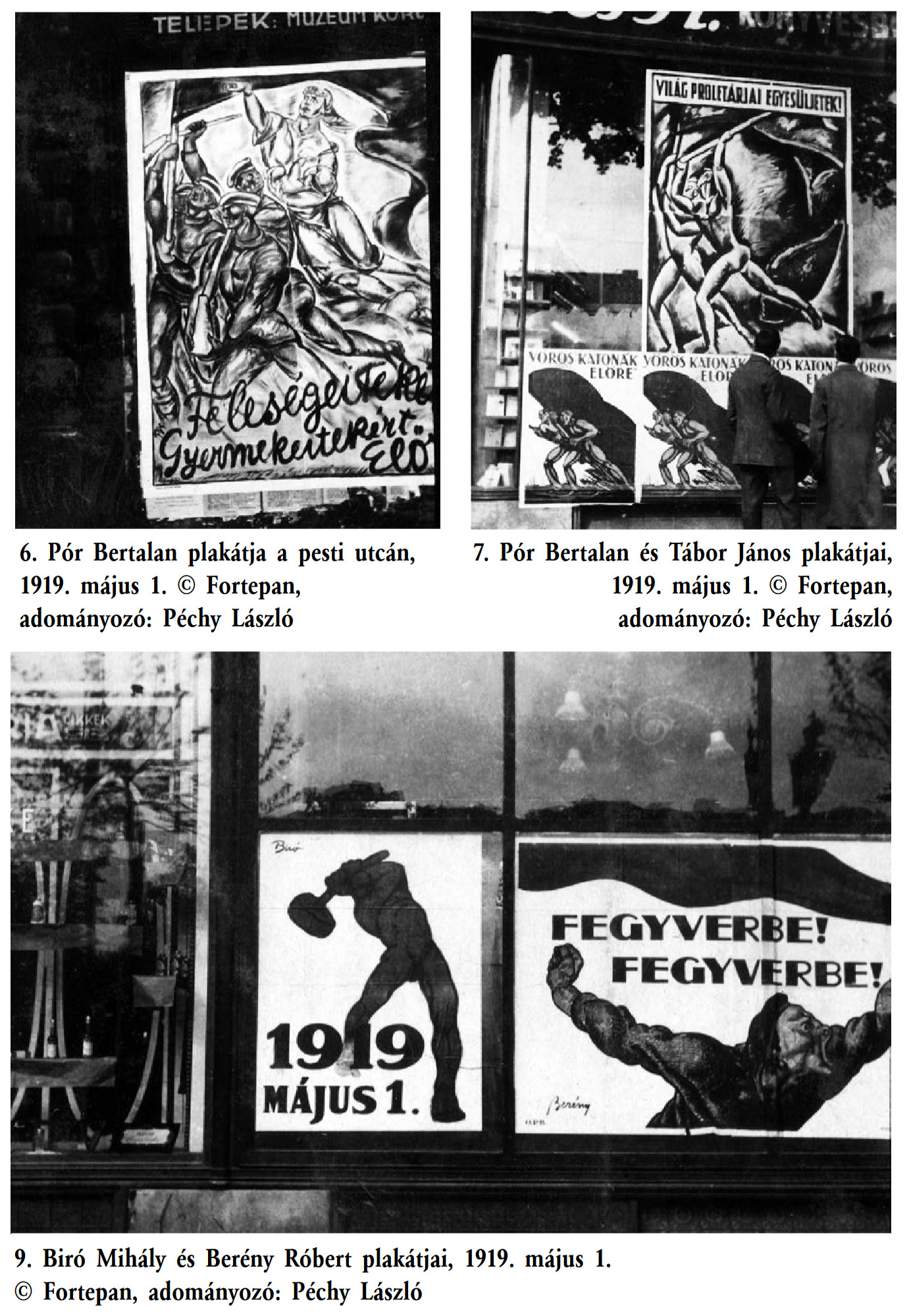

Celebrating the 30th anniversary of the Bund in Warsaw, 1927 (source: yivoarchives.org) Posters of Bertalan Pór-Pollacsek, János Tábor-Taupert, Mihály Bíró-Weinberger and Róbert Berény-Bakofen for the Soviet Republic on May 1, 1919. (Published in Rockenbauer, 2018)

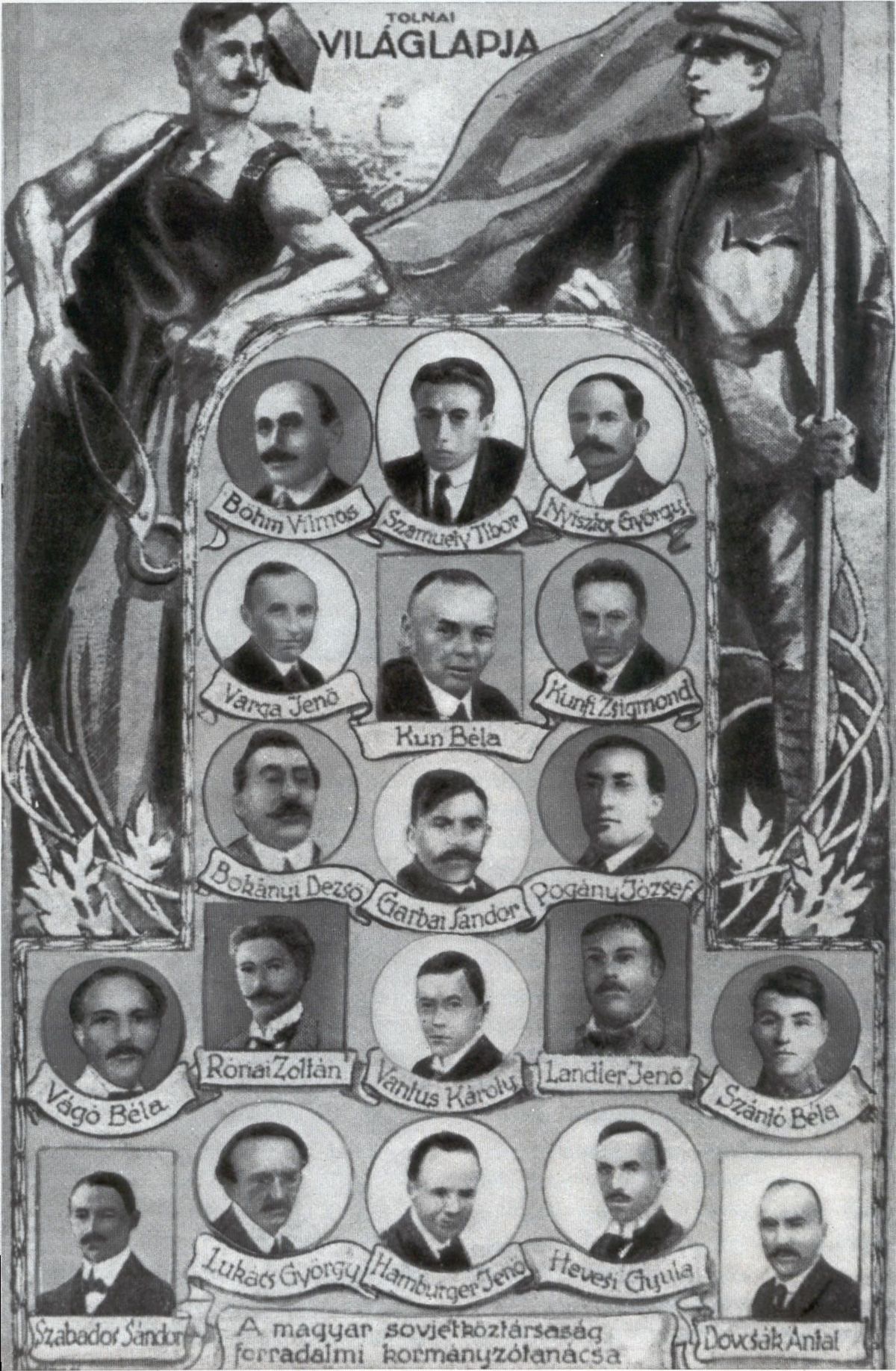

Posters of Bertalan Pór-Pollacsek, János Tábor-Taupert, Mihály Bíró-Weinberger and Róbert Berény-Bakofen for the Soviet Republic on May 1, 1919. (Published in Rockenbauer, 2018) A newspaper celebrates the new “Hungarian” Bolshevik government, whose personnel kept changing, but in this installation, 14 of the 19 are Jews – 73.6% (gentiles: Garbai, Nyisztor, Vantus, Dovcsák, Bokányi)

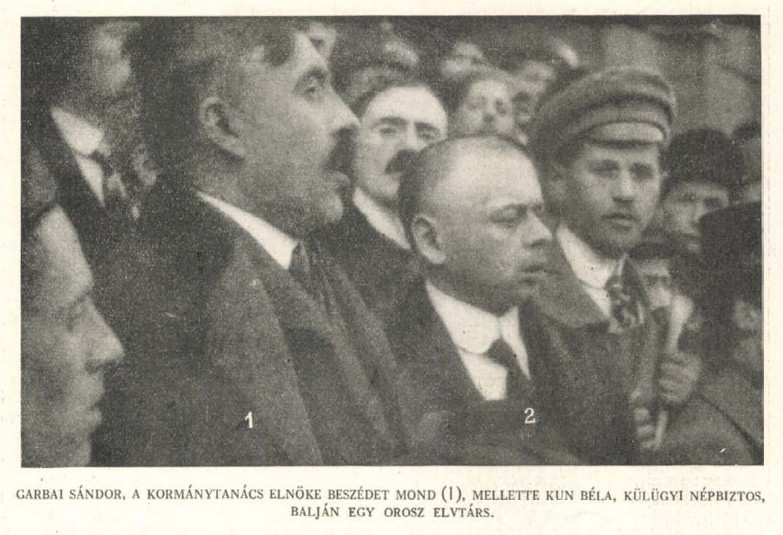

A newspaper celebrates the new “Hungarian” Bolshevik government, whose personnel kept changing, but in this installation, 14 of the 19 are Jews – 73.6% (gentiles: Garbai, Nyisztor, Vantus, Dovcsák, Bokányi) Sándor Garbai (1) with Béla Kun (2) on March 23, 1919.

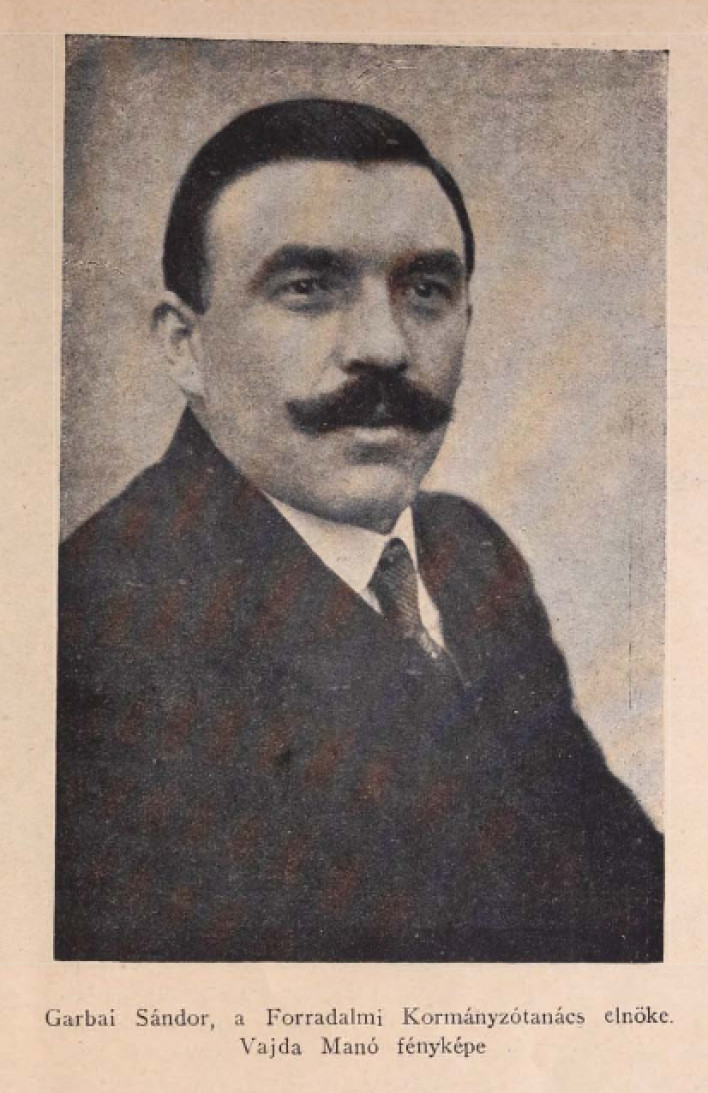

Sándor Garbai (1) with Béla Kun (2) on March 23, 1919. Sándor Garbai

Sándor Garbai Tibor Szamuely speaks on recruitment day in Heroes’ Square

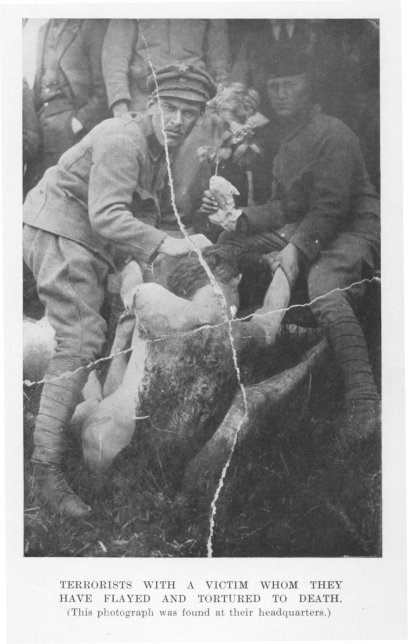

Tibor Szamuely speaks on recruitment day in Heroes’ Square Photograph ripped to pieces and thrown away at a headquarters portraying some of the Lenin Boys with their victim (source: Tormay, 1923)

Photograph ripped to pieces and thrown away at a headquarters portraying some of the Lenin Boys with their victim (source: Tormay, 1923)