Lists

In our wild youth, we used to say that people were “on the list” if we had a bone to pick with them. Unfortunately, we didn’t have such a list, as it would have been far too long and unwieldy. Today, I would probably keep positive lists instead. Unfortunately, that would be more manageable!

However, there are other lists that are far more dangerous – and which rarely attract the attention of the general public. One such list is the EU sanctions list. It recently attracted new attention when sanctions were imposed on the Swiss author, analyst, and commentator Colonel Jaques Baud. Mr. Baud is a retired colonel in the Swiss intelligence service specializing in the Warsaw Pact countries. He has also been affiliated with the UN and, as an expert on Africa, has been sent to several of the continent’s hot spots as a mediator, etc. His entire impressive career is documented on English Wikipedia. Now he has been added to the EU’s sanctions list because his analyses of the war in Ukraine do not correspond with the EU’s established policy. He is accused of allegedly spreading misinformation and conspiracy theories. Have we heard these terms before? Yes, they are meaningless words in themselves, because they presuppose that there is a recognized authority that can determine exactly what is true and what is false. And, of course, no such authority exists. In the exact sciences, there are of course things that cannot be debated – for example, that there are only two sexes – but when it comes to political analysis, it is not quite so simple. That is why we have analysts – and they do not always agree, of course, and they naturally form their own opinions based on their general knowledge of the issues. Most Western politicians, including EU and NATO leaders, lie – deliberately – every time they open their mouths and talk about the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. They always begin with the phrase “Putin’s unprovoked aggression,” and they always forget to mention the real root causes of the conflict. If they claim that they are not deliberately lying, it only proves that their intelligence and general knowledge leave a lot to be desired. In any case, they spread misinformation and conspiracy theories about Putin, Russia, and Ukraine. But they are not on any sanctions list for that reason. Jacques Baud’s analyses are inconvenient, however, because they expose politicians’ web of lies – or at least cast doubt on their self-assured opinions. And that is what democracy and freedom of expression are all about…

Among Baud’s crimes is that in 2016 he stated that there was no evidence that Osama bin Laden had played any role in the attacks of September 11, 2001. He did not say that bin Laden had played no role – he simply saw no evidence. And then he is blamed for quoting Oleksiy Arestovych, who was an adviser to the Ukrainian president, as saying that Ukraine provoked the Russian attack in an attempt to involve NATO. He has said that Putin is not out to conquer all of Ukraine, but to demilitarize it, which is true, but it is classified as “misinformation” because that is what the Kremlin claims, and by definition that is just propaganda. And so on. The list is long.

The bottom line is that there is only one “truth,” and that is the one put forward by the relevant authorities. I have always believed that it was the job of the press and independent analysts to verify such official truths – because if not, we are back in the Soviet Union, where “the truth” could be read every day in Pravda. We must therefore forget all about a free and independent press; we can make do with the Orwellian Ministry of Truth, whose motto is “Ignorance is Strength.” Baud is accused of being paid by the Kremlin, but unlike many other commentators, Baud has deliberately refrained from appearing in the Russian press and on Russian television – but of course he cannot prevent people from quoting him.

The Wikipedia page has a long list of his “crimes.” But even if some of what he says may later turn out to be wrong, that is precisely the right you have in a democratic society. The right to be wrong. Yes, you even have the right to deliberately lie in political debate – at least, people do it diligently. But what should we do about politicians when history shows that they were wrong—or perhaps more accurately, that they deliberately lied? Their incorrect analyses have had consequences—they have impoverished us and destroyed Europe even more than it already was—and they are responsible for the deaths of a few million Ukrainians. In the worst case, they will lead us into a nuclear war. As we know, “conspiracies against peace” were a crime at the Nuremberg Trials. When the current Section 266b of the Criminal Code was introduced, there was also a proposal to make it a criminal offense to agitate for war, but the then Minister of Justice, Knud Thestrup, believed that agitating for Denmark to go to war was hardly a punishable offense… When I listen to the current war rhetoric, I am disgusted, and I beg to differ with Thestrup: They should be punished. But in 1970, it was unimaginable that politicians could be as insane as they are today, but over 50 years of dumbing down and democracy in union have left their mark.

We can summarize it by saying that today you have no freedom of speech if you don’t believe “the right thing” – because ultimately, the core of this is precisely freedom of speech. That is what this is primarily about.

But what does it mean to be on the EU’s sanctions list? Well, it’s worse than going to prison. Your assets are frozen, your bank accounts are closed, you can’t have a credit card, you can’t fly, you can’t travel across borders – in short: you can’t live! The restrictions also apply to your family (what was called Sippenhaft in Hitler’s Germany!), and third parties are prohibited from giving you money.

And Jaques Baud is not the first, he is just the most prominent. The same has previously happened to a large number of German journalists who have written the truth about Russia.

The economic death sentence is handed down by unelected bureaucrats on behalf of unelected politicians. You have no opportunity to defend yourself, there are no avenues of appeal, no opportunities to complain – nothing. Is this what we are to understand by the rule of law? Not in my view! And this is yet another reason why we must not only leave the EU – we must abolish this entire parasitic organization, which is now also shamelessly taking out loans on our behalf. And there must necessarily be a legal reckoning following the same guidelines and with the same penalties and the same legal certainty as in Nuremberg. Perhaps one should invest one’s savings in Daka shares…

However, there are also other lists, such as the US terror list, which includes all the real or non-existent terrorist organizations created by the CIA. Before writing about any organization, one should check whether it is on that list, because if so, one must be careful what one writes, so as not to inadvertently become guilty of supporting or glorifying terrorism in Denmark as well. However, this list also includes individuals, e.g., Syria’s current president, al-Julani, was on the list (reward of USD 10 million). He was accused of single-handedly beheading his opponents. This can probably be classified as terrorism. However, the list also includes Fredrik Vejdeland, the leader of Nordfront, and he is therefore also on the Swedish list. What terrorism has Vejdeland committed? Absolutely none. He has been convicted of violating the section on “incitement against ethnic groups,” which corresponds to the Danish § 266b, but this can hardly be described as terrorism, cf. al-Julani, Osama bin Laden, and other people of that caliber.

But again, there is no possibility of defense, no possibility of appeal, nothing. It is a purely bureaucratic measure. Rule of law? Forget it, it no longer exists! The consequences are largely the same as for Jacques Baud, but Vejdeland cannot have an official job either, because then you need a salary account. And even if he can get a job where he is paid with real money (i.e., under the table), you can’t use cash for much in Sweden—only in grocery stores. They haven’t been abolished, but most businesses refuse to accept them. Sweden is always ahead when it comes to the road to ruin—but we always follow. Be on your guard!

Vejdeland believes that the Swedish government put him on the US terror list in connection with giving the US bases in Sweden. After all, Vejdeland has had nothing whatsoever to do with the US. Something for something! Al-Julani was removed from the terror list just as easily as he was added to it. For Vejdeland, the situation is different…

Fredrik Vejdeland has a sick wife and eight (8) minor children!

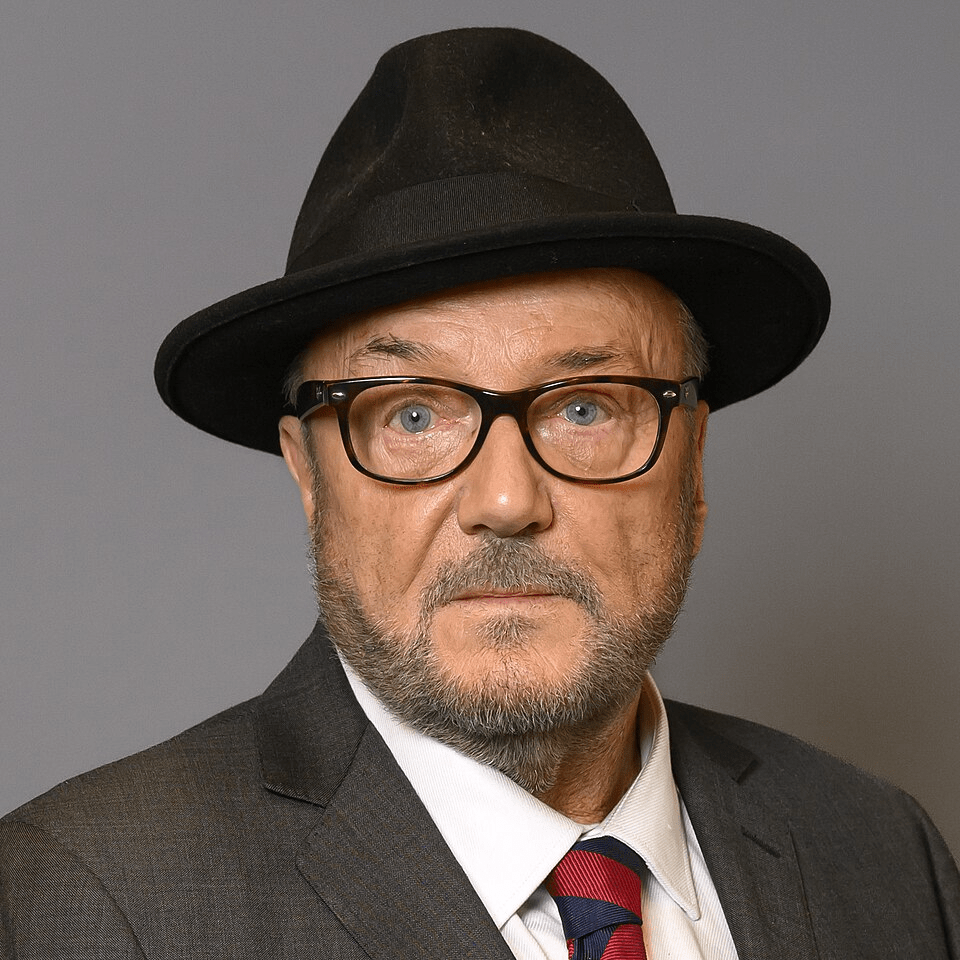

It is also wrong in England. George Galloway, a long-standing member of the British Parliament and leader of the Workers Party of Britain, was detained at the airport with his wife – without being arrested, because that would have given him rights. He was subjected to cross-examination about his political views. When he was released, he left the country, knowing that he was “on the list.” Today, he lives in freedom in Moscow. Listen to him on Mother of All Talkshows (MOATS) on YouTube. If I were younger, I would not hesitate for a moment to join him.

If you are a dissident, you might as well prepare yourself for total war with the system.

Travel video: https://cloud.mail.ru/stock/8mbJ99u6uB1zhcWAVxAsKQhm

Related articles:

Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), Two Lawyers Conversing

Honoré Daumier (1808–1879), Two Lawyers Conversing

How to end anti-Semitism for ever

How to end anti-Semitism for ever Semitic synergy: how Jews use and abuse Muslims to benefit themselves

Semitic synergy: how Jews use and abuse Muslims to benefit themselves The great David Irving speaks the truth about World War Two

The great David Irving speaks the truth about World War Two