Contra Camera: On Photography, Film and TV as Engines of the Anti-Human, Unenchanted and Immoral

Ich habe meinen Tod gesehen! That’s one of the most plaintive and poignant things I’ve ever read. Ironically enough, it’s also one of the most penetrating. In English it goes: “I’ve seen my death!” That’s what Anna Bertha Röntgen, wife of the German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen, reportedly said in 1895 after she saw an X-ray photograph he had taken of her left hand. The bones were clearly visible, you see, and so she foresaw herself as a soul-less, lifeless skeleton. And you can see her bones, because this is the photograph, still here long after the death it foretold to her:

A hand and a horror: the first medical X-ray (image from Wikipedia)

A hand and a horror: the first medical X-ray (image from Wikipedia)

Anna Bertha cried out against technocentric modernity in its early days, when technology was only just beginning to perform marvels like that. For her the marvel of X-rays was also a horror. And she was right in some very important sense, although it’s hard for us to recapture her emotion, when such images have been routine for many decades. Indeed, countless people today would find her reaction amusing. They’d like to be able to photograph or film her distressed face for LOLs or lulz. I call that kind of photographic sadism gelotography (from Greek γέλωτο-, gelōto-, “laughter”).

Gelotography is a much younger cousin of pornography, an anti-human genre that began almost as soon as photography itself did. Where one pursues the dopamine-dump of orgasm at any expense, the other pursues the dopamine-dump of laughter.[1] Accordingly, pornography and gelotography are part of why I’d say the camera is a wonderful evil, one of the two great unenchanting engines of technocentric modernity. The other great engine of unenchantment and evil is the car, which the conservative writer Russell Kirk once described as “the mechanical Jacobin,” as “a revolutionary the more powerful for being insensate. From courting customs to public architecture, the automobile tears the old order apart.”

Language as lightning

“Mechanical Jacobin” is a wise and wonderful phrase, a lightning-like metaphor that links cars with the arrogant, mass-murdering, tradition-trashing, society-smashing Jacobins of the French Revolution. And yes, cars and the infrastructure that serves them have been like Jacobins: transforming and tyrannizing cities and landscapes, assaulting the eye and ear and nose with metal, tarmac and concrete, with engine-noise, tyre-rumble and exhaust-fumes. And ironically enough, Kirk’s phrase illustrates one of the themes of this essay: the superiority of language over imagery, of words over pictures. I say “ironically enough,” because how would you illustrate that phrase? How would you convey Kirk’s meaning in pictures? On the printed or pixelated page, you understand it in an instant: “mechanical Jacobin.” Putting it into pictures would be much more difficult and time-consuming.

But the difficulty of illustrating an idea or capturing a scene has its salutary side when you compare illustration by hand with taking a photo. One of the charges I want to lay against photography is that it has cheapened reality, giving us too much with too little effort. With a camera, you can capture all the detail and depth of an entire landscape in an instant. And thereby you diminish the depth and denigrate the detail. That doesn’t happen when you try to paint or draw a landscape. Or paint or draw something much smaller and simpler, like a cup or a flower or a face. When you learn to paint or draw, the true richness, complexity and depth of the world are brought clearly before you in a way that simply doesn’t happen with a camera.

The Watcher Watched

So I’d echo Kirk’s anathema against cars by saying that cameras are mechanistic Jacobins. They cheapen reality and they corrupt morality. In Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), George Orwell presented a nightmare society where “You had to live — did live, from habit that became instinct — in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinized.” But that was the state invading privacy with cameras and microphones. Now the mechanistic invasion of privacy has been privatized:

“We had sex in a Chinese hotel, then found we had been broadcast to thousands”

One night in 2023, Eric was scrolling on a social media channel he regularly browsed for porn. Seconds into a video, he froze. He realised the couple he was watching — entering the room, setting down their bags, and later, having sex — was himself and his girlfriend. Three weeks earlier, they had spent the night in a hotel in Shenzhen, southern China, unaware that they were not alone.

Their most intimate moments had been captured by a camera hidden in their hotel room, and the footage made available to thousands of strangers who had logged in to the channel Eric himself used to access pornography. Eric (not his real name) was no longer just a consumer of China’s spy-cam porn industry, but a victim.

Warning: This story contains some offensive language

So-called spy-cam porn has existed in China for at least a decade, despite the fact that producing and distributing porn is illegal in the country. But in the past couple of years the issue has become a regular talking point on social media, with people — particularly women — swapping tips on how to spot cameras as small as a pencil eraser. Some have even resorted to pitching tents inside hotel rooms to avoid being filmed.

Last April, new government regulations attempted to stem this epidemic — requiring hotel owners to check regularly for hidden cameras. But the threat of being secretly filmed in the privacy of a hotel room has not gone away. The BBC World Service has found thousands of recent spy-cam videos filmed in hotel rooms and sold as porn, on multiple sites. […]

Eric, from Hong Kong, began watching secretly filmed videos as a teenager, attracted by how “raw” the footage was. “What drew me in is the fact that the people don’t know they’re being filmed,” says Eric, now in his 30s. “I think traditional porn feels very staged, very fake.”

But he experienced what it feels like to be at the opposite end of the supply chain when he found the video of himself and his girlfriend “Emily” — and he no longer finds gratification in this content. (“We had sex in a Chinese hotel, then found we had been broadcast to thousands,” BBC News, 6 February 2026)

So the biter was bit, the watcher was watched, the wanker wanked over. And feminists no doubt wish this biter-being-bit could happen more often to voyeuristic males invading the privacy of vulnerable females. Stories like that have been appearing for a long time at leftist outlets like the BBC and Guardian. But some of the leftists who decry the invasion of privacy for pornographic ends do not decry the invasion of privacy for political ends. For example, what about when someone is captured on camera in a private setting being racist or transphobic? “Ah, that’s different!” some leftists would say. As a racist and transphobe myself, I obviously don’t agree. And I can use my opposition to pornographic privacy-invasion to support my transphobia. Why should so-called “transwomen” not be allowed to enter female spaces like dressing-rooms and toilets? Well, one good reason is that the male perverts in question won’t be able to plant spy-cameras there.

No female Mozart

Real women do that sort of thing much less often, which is why I was puzzled by this headline back in March 2025: “Woman jailed for recording hundreds of men using the toilet in Aldi.” In fact, it wasn’t a woman but a “transwoman,” that is, a male pervert called John Leslie Graham. And it isn’t a coincidence that men are both corrupted by cameras and creators of cameras. That is, it’s men who invent the technology that other men use for voyeurism and privacy-invasion. As the provocateur Camille Paglia once put it: “There is no female Mozart because there is no female Jack the Ripper.”

Men break boundaries criminally, creatively and cognitively in ways that women don’t. Recall the story at the beginning of this essay. It’s impossible to imagine the sexes in that story reversed, with a female physicist called Anna Bertha Röntgen creating X-ray photography and her husband Wilhelm crying “Ich habe meinen Tod gesehen!” Women don’t invent like that and men don’t emote like that. That cry was authentically female, the lament of an utterly ordinary and unexceptional woman at the cleverness and skill of her husband, who’s still famous and still celebrated as the discoverer of X-rays. And yes, we can certainly agree that the husband was far more intelligent and inventive than the wife. But we might also agree that he had far less wisdom.

Breaking the white light

And that story of a technophilic man and a technophobic woman reminds me of another story about a clever technophile and a wise technophobe. It’s a story in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, when the wizard Gandalf is describing how he sought the aid of the wizard Saruman against the Dark Lord Sauron. Saruman’s name means “Man of Skill” or “Man of Cunning,” because he is skilled at molding and manipulating matter to his own ends, as Gandalf sees again during their dialog:

“The Nine have come forth again,” I answered [Saruman]. “They have crossed the River. So Radagast said to me.”

“Radagast the Brown!” laughed Saruman, and he no longer concealed his scorn. “Radagast the Bird-tamer! Radagast the Simple! Radagast the Fool! Yet he had just the wit to play the part that I set him. For you have come, and that was all the purpose of my message. And here you will stay, Gandalf the Grey, and rest from journeys. For I am Saruman the Wise, Saruman Ring-maker, Saruman of Many Colours!”

I looked then and saw that his robes, which had seemed white, were not so, but were woven of all colours. and if he moved they shimmered and changed hue so that the eye was bewildered.

“I liked white better,” I said.

“White!” he sneered. “It serves as a beginning. White cloth may be dyed. The white page can be overwritten; and the white light can be broken.”

“In which case it is no longer white,” said I. “And he that breaks a thing to find out what it is has left the path of wisdom.”

“You need not speak to me as to one of the fools that you take for friends,” said he. “I have not brought you hither to be instructed by you, but to give you a choice.” (The Fellowship of the Ring, 1954, Book II, chapter 2, “The Council of Elrond”)

Gandalf refuses the choice, just as he refuses to be impressed by Saruman’s boast that “the white light can be broken.” There I’d say that Tolkien was making an implicit reference to — and rejection of — the mechanistic, mathematicized world-view of the great English physicist Isaac Newton (1643-1727). It was Newton who explained why white light can be “broken” with a prism into the visible portion of the electromagnetic spectrum (where X-rays would later be found by the German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen). If I’m right, then Saruman is a spokes-wizard for the nihilism of Newtonianism, for the foolish cleverness of science and technology. He has what is later described as “a mind of metal and wheels” and “does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him for the moment.” (The Two Towers, “Treebeard”)

Books are bigger

I haven’t seen that confrontation between Gandalf and Saruman in the very successful film-trilogy of Lord of the Rings. Yes, it would be interesting to see it, but also invasive. Someone else’s images would invade my head and overwhelm the private, personal images I’ve always created when I’ve read and re-read Lord of the Rings. That’s one of my other objections to film and one of my other reasons to elevate literature over film and photography. The potency of the image overwhelms and obliterates the privacy of the imagination. And yet books — those silent, inert rectangular blocks of printed paper — are far bigger than booming, bustling, broad-screen movies, with all their action and activity and energy. Books remind me of the famous saying by the Greek philosopher Heraclitus: Δὶς ἐς τὸν αὐτὸν ποταμὸν οὐκ ἂν ἐμβαίης, Dis es ton auton potamon ouk an embaiēs — “You cannot step twice into the same river.” Readers of Lord of the Rings have never experienced the same book. Viewers of Lord of the Rings have always experienced the same film.[2] In other words, readers cook the book for themselves from the ingredients supplied by Tolkien; viewers consume what was cooked for them by the director Peter Jackson and the many others who created the films.

Film is tyrannical — sense-seizing, attention-appropriating, imagination-obliterating — in a way that literature isn’t. Film is also collectivist where literature is individualist. With Lord of the Rings, what one man created on paper took hundreds or thousands of men and women to put onto film. As the English writer Alan Moore once said: “[T]he written or spoken word is a higher technology than film. I believe it is much more genuinely magical in its effects and much more human. I’m not ignorant or dismissive of cinema. But with the written word, any writer has got exactly 26 characters. Out of the rearrangements of those 26 characters, the writer can create anything.”[3]

Definitely disenchanting

Artificial intelligence has narrowed that gap between the individualism of literature and the collectivism of film. It’s allowing entire films to be created with minimal expense and effort by single individuals. But the tyrannizing, sense-seizing evils of film have remained. And the privacy-stripping, amorality-encouraging evils of film have been encouraged. AI allows any kind of obscenity or extremity that can imagined to be literally turned into images. And so AI becomes part of the disenchantment of technocentric modernity, the Entzauberung der Welt or the stripping of magic and mystery from life named by the German sociologist Max Weber in 1917 from a poem by the German poet Friedrich Schiller. Film and photography disenchant in part because they make definite in a way that language and literature don’t. For example, what did Helen of Troy look like? Language both can and can’t tell us. From the 1590s, the English playwright and poet Christopher Marlowe tells us like this:

Was this the face that launch’d a thousand ships

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium? (Doctor Faustus, Act V, scene 1, lines 161-2)

But Marlowe also doesn’t tell us, because there’s no description of Helen’s face there, nothing about the shape, color, contours and myriad other features of a face which cameras can capture with such ease. And have captured in films about the Trojan War, where real actresses have embodied the literally mythic beauty of Helen of Troy. And where real sets have represented the “topless towers of Ilium.” Or failed to represent them, because how do you represent “topless towers”? The concept works in words, but would be impossible or absurd to convey on film.[4] Marlowe’s words are more wonderful and more powerful than any film or photograph because they are indefinite in a way film and photography can’t be and don’t want to be. Indeed, you could say that Marlowe wrote a kind of meaningful music about Helen’s beauty: all his words have meanings and some refer to material things, but they float in the mind like music, untethered to any particular manifestation of materiality.

Instant over hours

He was writing poetry, of course, but you can say the same of mathematical language. The word “triangle” floats free of materiality too, encompassing all triangles but embodying no particular triangle. Film and photography always want to manifest the particular, so triangles are tethered there. And so are trees and towers. And the face of a mythic beauty like Helen of Troy. Or the face of a historic beauty like Cleopatra. She was embodied by the actress Elizabeth Taylor in the hugely expensive film Cleopatra (1963), with its crew of hundreds and cast of thousands. And let’s suppose that the film had been the masterpiece it aimed to be. Let’s suppose it had been the greatest film ever created. I still think its hours of imagery and action would have been less powerful and less of an art-work than a single second of Cleopatra’s life illustrated by one man with much less advanced technology in the nineteenth century:

The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra (1885), by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (image from Wikipedia)

The Meeting of Antony and Cleopatra (1885), by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (image from Wikipedia)

That’s one of the best paintings by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912), the Anglo-Dutch master who achieved a kind of full-color photographic realism in paint long before photography itself was routinely and realistically in color. Looking at that painting, one can almost feel the heat of the sun, smell the sea-air and the roses, hear the music of the flute, the creaking of the galleys, the splash of the oars. And in the “almost” is the enchantment. Alma-Tadema had to conjure that scene in the viewer’s mind with nothing but paint on canvas. And with his own long-honed, hard-earned skill, of course. The painting invites the imagination in a way that a film of the same scene wouldn’t and couldn’t. When we see the painting, we imagine what happened before and will happen next. A film would show us what did and will happen. And nowadays there would likely be sex. If all art aspires to the condition of music,[5] then perhaps you could say that all film aspires to the condition of pornography: ever more exciting, ever more explicit, ever more extreme, obscene and evil.

But the evil of film lies less in its pornography than in its pseudography, that is, in its ability to convey lies and falsehoods in a convincing, quasi-realistic way. Film and its retarded younger brother television have been peddling lies about racial and sexual differences for decades, portraying Blacks as wise and noble victims of White oppression, presenting women and homosexuals as superior to straight White males, who are thrust on film where leftism wants them to be in reality: at the bottom of all moral, cultural and cognitive hierarchies. And there lies a great irony: the technology created by White men has been used to overthrow White men and elevate their enemies. Photography, film and TV were all created by the cunning hands and clever brains of White men like the French Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), pioneer of photography, the American Thomas Edison (1837–1941), pioneer of cinema, and the Scot John Logie Baird (1888–1946), pioneer of television. What was invented and perfected by White men was then turned against White men.

Toppling giants, elevating dwarves

But part of the camera-driven undermining of White men wasn’t planned and purposive. Why was the Anglo-Dutch master Lawrence Alma-Tadema an artistic hero in the nineteenth century and the Jewish charlatan Mark Rothko an artistic hero in the twentieth? Because the camera mechanized the representation of reality and thereby corrupted art, driving it away from realism and beauty and towards abstraction and ugliness. Alma-Tadema was hugely skilled; Rothko was hugely hyped. Indeed, Rothko and other charlatans were beneficiaries of what the American journalist Tom Wolfe called The Painted Word (1975), whereby art became centered not on the skill and talent of disproportionately White masters, but on the words and theories of disproportionately Jewish scholars and critics.

Rothko wrecks reality, then embraces abstraction (see Brenton Sanderson’s “Mark Rothko, Abstract Expressionism, and the Decline of Western Art” at TOO)

Rothko wrecks reality, then embraces abstraction (see Brenton Sanderson’s “Mark Rothko, Abstract Expressionism, and the Decline of Western Art” at TOO)

The camera indirectly created the Painted Word, toppled artistic giants like Alma-Tadema and elevated artistic dwarves like Rothko. Meanwhile, Jews in Hollywood and New York were turning the White male inventions of film and television against Whites in general and White males in particular. But cameras would have been catastrophic without the K-words. What cars have done to landscapes, cameras have done to mindscapes. And the two inventions collaborated in wreaking havoc on our culture. Cameras and cars have been the two great unenchanting engines of technocentric modernity.

[1] I dislike the modern fashion for referring to or explaining human motives and behavior in reductive, neurochemical ways: “dopamine rush” and so on. It’s crude, cursory and disenchanting. But reductionism seems entirely appropriate for pornography and gelotography.

[2] And a single reader has never read the same book twice.

[3] Alan Moore has also said: “I find film in its modern form to be quite bullying[.] It spoon-feeds us, which has the effect of watering down our collective cultural imagination. It is as if we are freshly hatched birds looking up with our mouths open waiting for Hollywood to feed us more regurgitated worms [..]”

[4] “Topless” can be interpreted as “having no limit in height” or “unexceeded in height.” Either way, it can’t be easily or unabsurdly represented as an image.

[5] Walter Pater said this in The Renaissance: Studies in Art and Poetry (1877): “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music. For while in all other works of art it is possible to distinguish the matter from the form, and the understanding can always make this distinction, yet it is the constant effort of art to obliterate it.” See Gutenberg text.

K.M. Breakey

K.M. Breakey Two thuggish Black criminals, two manufactured martyrs: George Floyd and Sheku Bayoh

Two thuggish Black criminals, two manufactured martyrs: George Floyd and Sheku Bayoh Hannah Lavery (second right) “

Hannah Lavery (second right) “ New poet and true poet: the Black Zimbabwean Tawona Sitholè and the White Scot Rabbie Burns

New poet and true poet: the Black Zimbabwean Tawona Sitholè and the White Scot Rabbie Burns

Winged in a wheelchair: Rosemary Sutcliff and her most famous book

Winged in a wheelchair: Rosemary Sutcliff and her most famous book Nietzsche says “Nein!” to Marx

Nietzsche says “Nein!” to Marx Alien faces, alien races: Rosemary Sutcliff was not writing for non-British children like these (

Alien faces, alien races: Rosemary Sutcliff was not writing for non-British children like these (

Wagner’s grandson and daughter-in-law with Hitler

Wagner’s grandson and daughter-in-law with Hitler Joseph Goebbels attending the Bayreuth Festival in 1937

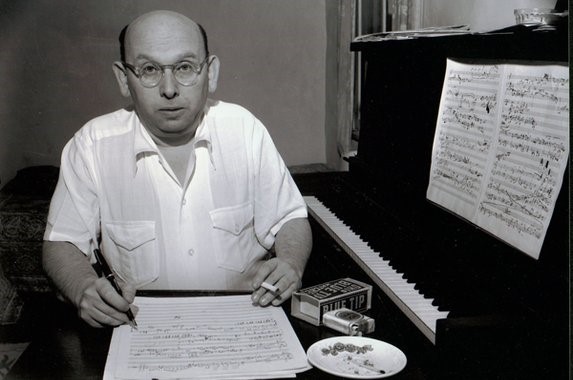

Joseph Goebbels attending the Bayreuth Festival in 1937 Jewish communist composer Hanns Eisler

Jewish communist composer Hanns Eisler