Les Judéo-Bolcheviks dans les exécutions de masses :

le cas de Rozalia Zemliachka en Crimée en 1920

Karl Nemmersdorf

Introduction

Il est bien connu dans notre mouvance que les Juifs sont à l’origine d’une liste effroyable d’atrocités en Union soviétique. Sa seule échelle dépasse l’entendement. De 1917 à 1953, des millions de Russes ont été victimes d’arrestations, de torture, d’exécutions, des millions sont morts dans les Goulags, et d’autres encore sont morts par millions de famines d’État. Au sommet de l’appareil, des Juifs, on le sait, mais qui, lequel ou laquelle précisément s’est occupé de telle ou telle répression, de telle ou telle campagne de massacre? Ça reste souvent vague [1]. Le but du présent article est justement d’établir un lien précis entre un certain noyau de Juifs et un massacre resté célèbre, celui de Crimée fin 1920. Nous aurons pour fil rouge, c’est le cas de le dire, la trajectoire d’une communiste particulièrement enragée : Rozalia Zemliachka. Tout du long, une carrière sans faille, sans écart, sans faiblesse: elle entre au mouvement en 1896, participe à la révolution de 1905 et de 1917, est nommée commissaire politique des armées durant la guerre civile, puis a fidèlement servi le régime stalinien qui lui allait comme un gant. Elle aura reçu les plus hautes distinctions et s’éteindra naturellement, c’était plutôt rare à l’époque, en 1947. Elle est inhumée sur la place Rouge, comme une grande figure du Parti qu’elle était. C’est elle que Lénine enverra en Crimée à la fin de la guerre civile pour liquider les derniers éléments hostiles à l’établissement sur Terre du communisme. On pense parmi les historiens, que le bilan des massacres s’est élevé en quelques mois à 50 000.

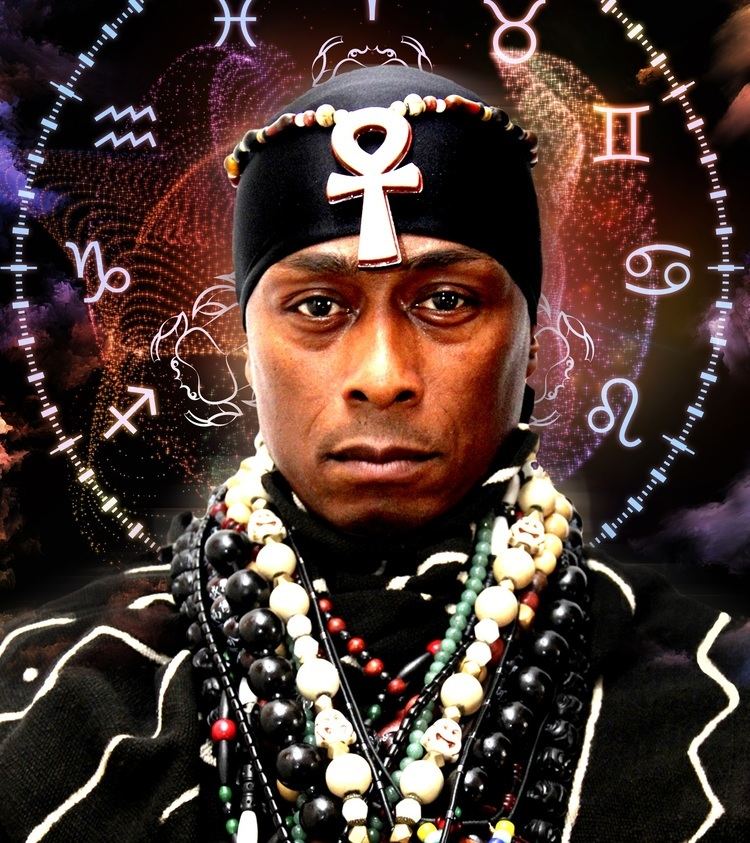

Rozalia Zemlichka

Jeunesse. Rozalia Samoilovna Zalkind, dont le nom de clandestinité était Zemliachka (« compatriote »), est née en 1876 dans une famille juive.[2] Son père, Samuel Markovich Zalkind, était un riche marchand de Kiev, ce qui n’a pas empêché toute la famille, filles et garçons, de se joindre, sans égards pour l’esprit de classe, à un mouvement révolutionnaire décidément très juif dès le départ [3] [4]. Il y avait une Juive parmi les conjurés auteur de l’attentat dont a été victime, en 1881, le Tsar Alexandre II.[5] Non seulement les Zalkind approuvaient l’assassinat, mais il n’est pas exclu que la famille entretenait des liens avec les régicides. Leur maison a en tout cas été perquisitionnée par la police à la recherche de brochures illégales [6] et la petite Rozalia aura vu deux de ses frères se faire embarquer pour activités révolutionnaires.[7]

Rozalia a fait ses études secondaires à Kiev, en sortant diplômée à 15 ans. Déjà révolutionnaire, elle se rattachait à l’époque, sous l’influence de ses frères aînés, au mouvement populiste. Mais elle a vite bifurqué, le populisme se rattachait trop à la culture russe et à la paysannerie. En tant que Juive, elle se sentait un net penchant pour le marxisme, affranchi des nationalismes et des traditions, foncièrement internationaliste et tellement plus “scientifique”. Elle avait aussi vite remarqué que la classe ouvrière était plus à même de provoquer l’effondrement de l’ordre existant que la classe paysanne. [8] Comme Marx et beaucoup d’autres, ce n’est qu’en vertu des impératifs révolutionnaires qu’elle en est venue à s’intéresser au sort de la classe ouvrière et non l’inverse. [9]

Rozalia Zemlichka, comme toujours, l’âge accentue les caractéristiques éthniques

Carrière révolutionnaire

Son père l’avait envoyée à Lyon (!) pour faire médecine, mais en 1896, elle était déjà de retour en Russie, les sources divergent au sujet de savoir si elle est revenue avec un diplôme ou non, mais quoi qu’il en soit, dès lors, elle se consacre corps et âme à la révolution. Pour ses débuts elle prononce lors d’un meeting clandestin un discours sur « le mouvement ouvrier en Europe de l’ouest », ce qui lui vaut d’être arrêtée et jetée en prison. Elle en profite pour se plonger dans la littérature marxiste. La carrière de Zemliachka au sein du Parti Social Démocrate était lancée. [10] (Attention, pas de contresens, le Parti Ouvrier Social Démocrate Russe, c’est le parti qui engendrera, à la suite d’une scission au congrès de Bruxelles, le Parti Bolchevik). Elle fait deux ans de prison (1899–1901), en sort en s’étant forgé une âme de communiste indéfectible, prend un pseudonyme à la mesure de sa personnalité implacable :Tverdokamennaia, « dure comme le roc ». Mais elle ne dédaigne pas non plus de se fait aussi appeler « Démon », ce qui laisse songeur quant à la véritable nature de son affiliation. [11]

Lev Bronshtein, Trotsky pour les intimes, ne tardait pas à signaler Rozalia, son amie, à l’attention de Nadezhda Krupskaya, la femme de Lénine, lui adressant un rapport dithyrambique, y louant son tempérament révolutionnaire et son énergie, sans toutefois manquer de prévenir sur son autoritarisme et un certain manque de tact. Sur ce, Krupskaya, qui assistait son mari dans la direction des opérations du Parti depuis leur exil parisien, envoyait Rozalia prendre la tête de l’antenne clandestine d’Odessa. Rapidement,

Zemliachka s’est imposée dans le rôle. Dès mars 1903, la cellule d’Odessa était fermement aux mains des léninistes qui la désignaient comme déléguée au second congrès du Parti qui approchait. Zemliachka avait fait la preuve de son aptitude à commander, de son énergie et de sa capacité de travail. [12]

L’ami de Zemliachka Lev Bronshtein-Trotsky

Le 30 juillet 1903, Zemliachka assiste à Bruxelles au fatidique Deuxième Congrès du Parti Ouvrier Social Démocrate de Russie. (Le congrès fondateur s’était tenu en 1898 à Minsk, essentiellement sous les auspices du Bund ouvrier juif, de loin la plus grande organisation socialiste en Russie : quatre des neuf délégués de ce congrès étaient juifs.) Des quarante-trois délégués présents au deuxième congrès, vingt étaient juifs. [13] Du moins jusqu’à ce que la police belge ne l’expulse, Zemliachka a pu faire connaissance de Lénine et de Krupskaya, prendre part aux débats à leurs côtés en défendant l’idée – résolument non marxiste – d’un noyau dur devant amener les masses à venir s’abreuver aux sources de la révolution violente. L’intransigeance de Lénine sur ce point conduisait à une rupture avec les Marxistes modérés, plus respectueux de la démocratie, et qu’on allait désormais connaître sous le nom de Mensheviks « les minoritaires ». [14] Lénine profitait du vote pour proclamer sa faction «bolchevik», la majorité. La scission s’avérera définitive et Zemliachka se rangera aux côtés de Lénine, tout comme Joseph Staline, Yakov Sverdlov (Yankel Solomon), et Lev Kamenev (Rosenfeld), trois futures figures majeures. Trotsky s’éloignera un temps du côté des mencheviks, puis fera cavalier seul (il était notoirement arrogant), avant de rejoindre Lénine juste avant la révolution bolchevique de novembre 1917.

À l’issue du congrès, Zemliachka était cooptée par le Comité Central, marquant ainsi la reconnaissance de sa nouvelle prééminence. Elle était l’un des agents les plus actifs de Lénine en Russie. Elle était sur tous les points chauds, à Saint-Pétersbourg, aux meetings en Suisse et à Londres, partout elle s’affirmait avec force dans les débats, prônant les mesures les plus radicales pour renforcer le Parti et accélérer la Révolution, n’hésitant pas à remettre à leur place ses détracteurs. [15]

Pendant ce temps, la révolution de 1905 montait en pression. Après des frictions avec des membres de la cellule de Saint-Pétersbourg, Rozalia s’installe à Moscou et devient la secrétaire du Parti de l’antenne. Elle était contre le soulèvement qu’elle estimait voué à l’échec, mais lorsqu’une grève a dégénéré en émeute en décembre, elle était sur les barricades, tentant d’utiliser les wagons de tramway contre les forces de l’ordre. [16] (Les sources sur l’épisode sont minces et divergentes). [17]

Lors de la répression qui s’en est suivie, Zemliachka a été arrêtée et emprisonnée à Saint-Pétersbourg. Elle y contracte une tuberculose (son mari, Schmuel Berlin, en était mort en 1902) et souffre d’une maladie de cœur ; elle bénéficie d’une libération pour raison médicale. Elle part à l’étranger (1909) jusqu’au déclenchement de la Première Guerre mondiale, séjournant principalement en Suisse. Barbara Evans Clements affirme qu’elle a évité tout contact avec les émigrés révolutionnaires (Ils étaient des milliers en Europe de l’Ouest), mais une autre source affirme qu’elle était en étroite collaboration avec Lénine [18] « L’échec du soulèvement de 1905 l’avait profondément affectée, elle en rejetait la responsabilité sur les camarades, qui, selon elle, avaient laissé passer les opportunités qui s’étaient offertes . . .» [19] Elle ne rentre à Moscou qu’en 1914, reprenant discrètement ses activités militantes.

Après le renversement du Tsar par la révolution de février 1917 (qui n’est pas la révolution Bolechevik de novembre 1917 = Octobre rouge), elle soutient les exigences de Lénine d’un retrait immédiat de la guerre et d’une remise des pleins pouvoirs aux Soviets. À ce moment-là, virtuellement tous les socialistes, y compris une majorité de Bolcheviques, estimaient qu’il s’agissait de soutenir le gouvernement provisoire en attendant la réunion d’une Assemblée Constituante en vue d’une république constitutionnelle. Dans le cadre de la théorie marxiste, cela aurait représenté l’étape obligée de la « révolution bourgeoise» et du développement concomitant du système capitaliste, préalable à l’instauration du communisme suite à la lutte dialectique entre les travailleurs opprimés et les patrons. Cela pouvait durer des dizaines d’années, et Lénine n’était pas disposé à patienter, Trotsky et Zemliachka non plus. Ils se rendaient compte que le gouvernement provisoire était faible et qu’il suffisait de se baisser pour ramasser le pouvoir. La perspective du pouvoir a fait s’évaporer le primat des dogmes marxistes qu’ils avaient eux-mêmes soutenus dans leurs écrits. Au milieu de l’été, Rozalia demandait au comité du parti de Moscou de s’armer en vue de la prise de pouvoir. [20] Lénine et Trotsky tentaient également de convaincre les Bolcheviks réticents de Petrograd à faire de même. Avec succès puisque c’est à Petrograd que Trotsky fait tomber le pouvoir le premier, en novembre, Moscou suit en créant un Comité militaro-révolutionnaire sur le modèle de Petrograd. Le secrétaire du Comité est un certain Arkady Rozengolts, bien sûr un Juif, c’est lui qui joue le rôle prépondérant dans le soulèvement. [21] Zemliachka prend la tête des opérations dans l’un des districts de la ville (à nouveau, on manque de détails). Après quelques jours de combat, les maigres détachements du gouvernement provisoire sont vaincus, et les deux principales villes de Russie tombent aux mains des bolcheviks, en grande partie à l’initiative des Juifs.

Zemliachka dans la Révolution

Durant une grande partie de l’année suivante, Zemliachka continue de travailler pour le comité du Parti à Moscou, c’est une position cardinale puisque Lénine avait transféré la capitale de Petrograd à Moscou en mars, et tout le pouvoir s’y trouvait concentré. Toute l’année était marquée par des défis énormes : la guerre civile couvait sur plusieurs fronts, l’économie était quasiment à l’arrêt, et des troubles éclataient partout. Le peuple avait faim, le peuple était au chômage, le peuple grondait parce qu’il subissait les brimades et les spoliations des commissaires et des Juifs et qu’il n’avait pas peur de le dire. Les plus téméraires criaient à bas Zinoviev (Apfelbaum) lors des meetings de Petrograd dont il était le responsable. [22] Il ne s’agissait pas d’incidents isolés, même Lénine qui tentait d’amadouer la foule a été hué et a dû quitter l’estrade avec Zinoviev aux cris de « à bas les Juifs et les commissaires ». [23] Même des unités de l’Armée rouge se mutinaient, se livraient à des pogroms et exigeaient le départ des Juifs du gouvernement. [24] Les Bolcheviks se sentaient en état de siège, ils n’ont pas tardé, dès l’été, à avoir recours aux exécutions de masse et aux camps de concentration. Plusieurs assassinats d’officiels, souvent Juifs, et une tentative contre Lénine ont poussé le régime à déclencher le bain de sang de la Terreur Rouge à partir de septembre. [25] C’est précisément cette terreur qui sera à l’origine de la guerre civile qui va durer jusqu’à fin 1920.

Zinoviev-Radomyslsky (Apfelbaum), le patron de Petrograd

C’est dans cette atmosphère d’urgence pour le régime que Zemliachka décide de s’engager pour sauver le paradis communiste. Elle exige une affectation au front contre les Armées Blanches. Mais à 42 ans, il n’était pas question qu’elle mène les hommes au combat, et quel rôle pouvait-on confier à une femme ? Celui de commissaire politique, bien sûr. Là, elle pourrait haranguer les soldats, être derrière le dos des officiers, ordonner l’exécution de tous ceux qui ne sont pas contents des commissaires politiques Juifs.

Les commissaires politiques ont été créés pour ça : assurer le contrôle politique de tous ces paysans récalcitrants et de tous ces anciens officiers tsaristes suspects qui composaient l’essentiel de l’Armée Rouge. [26]

Ces commissaires, des hommes de confiance du régime, étaient ainsi incorporés dans toutes les grandes unités pour assurer l’endoctrinement des troupes et le contrôle des officiers. En fait, les opérations ne pouvaient se dérouler qu’avec l’aval des commissaires, qui avaient un rang égal à celui des officiers supérieurs et tous les ordres étaient contresignés d’eux. Est-il besoin de préciser que la plupart étaient Juifs ? [27]

De 1918 à fin 1920, Zemliachka aura ainsi été affectée à la tête, successivement, de la 8e et de la 13e armée, les deux opérant dans le sud de l’Ukraine. À la tête de son escouade politique (une douzaine d’éléments), elle couvrait environ un effectif de 80 000 hommes, pratiquement à l’égal du commandant en chef de l’unité. Elle aura pleinement eu l’occasion d’étaler son fanatisme et son énergie sur ce théâtre d’opération crucial, portant des vêtements d’hommes et une veste en cuir : « maintenant bien dans la quarantaine, le seul vestige de son passé bourgeois, c’était ce ridicule pince-nez qui jurait avec ses cheveux courts, ses bottes, son pantalon et sa veste en cuir ». [28] Travailleuse et efficace, elle avait l’œil à tout, de la rédaction des discours à l’hygiène personnelle. [29] Elle n’avait de cesse que l’annihilation des ennemis du règne rouge. « Nous devons être sans pité, combattre sans relâche les serpents qui se cachent … Nous devons les anéantir avec un balai de fer ». [30] Ce qui faisait écho au tristement célèbre appel de Zinoviev dans son discours public de septembre 1918 : « Sur les cent millions d’habitants que compte la Russie soviétique, nous devons en entraîner derrière nous quatre-vingt-dix millions. Quant au reste, nous n’avons rien à leur dire. Ils doivent être réduits à néant ». [31]

Zemliachka durant la Révolution

Dieu seul sait combien sont morts sur ordre de Zemliachka durant ces deux années au paroxysme de la Terreur Rouge et de la Guerre Civile. La phase véritablement apocalyptique aura été l’entrée en Crimée en 1920, après son évacuation par les Armées Blanches. Alors le monde a eu sous les yeux un exemple sanglant, sanguinaire, de ce qu’il en coûte à une population civile sans défense de refuser la domination juive.

Le Massacre de Crimée

Le Baron Wrangel et l’Évacuation de la Crimée.

À l’automne de 1920, les bolcheviks avaient affermi leur pouvoir; la Guerre Civile était pour ainsi dire gagnée. Seul le Baron Wrangel résistait encore dans son enclave en Crimée. Descendant d’une grande famille de la noblesse germano-balte qui avait servi à la fois la Prusse et la Russie, Peter Wrangel était une figure dominante de l’armée tsariste, un homme capable au caractère bien trempé. [32] Sa petite armée n’avait pas pour ambition de renverser le régime de Moscou, mais de tenir un territoire qui serait à la fois un refuge pour les anti-bolcheviks et un modèle de ce que pourrait être une Russie non communiste. Ils étaient des centaines de milliers, fuyant la Terreur rouge, à venir chercher sa protection en Crimée. Les Bolcheviks, naturellement, n’avaient nullement l’intention de laisser Wrangel créer sa petite république. Profitant de ce que la Guerre Civile s’achevait ailleurs et qu’il était mis un terme à la guerre en Pologne (grâce à l’intervention militaire française), les Rouges tournaient leurs forces contre ce dernier noyau de résistance.

Peter Wrangel, le Baron Noir

C’est le Général Mikhail Frunze, commandant du front sud, qui est chargé de nettoyer la poche de Crimée. Il était lui-même sous la coupe directe de Trotsky, Commissaire à la Guerre depuis mars 1918 et créateur de l’Armée Rouge. À ses côtés, un trio militaro – révolutionnaire dans lequel on retrouve deux Juifs, Béla Kun (Béla Kohn) et Sergei Gusev (Yakov Davidovich Drabkin). (Nous reviendrons plus bas sur ces deux derniers, ce sont eux qui sont à l’origine du bain de sang qui est l’objet de cet article). Frunze aligne 300,000 hommes face aux 70,000 de Wrangel. Les Blancs étaient néanmoins confiants parce que l’entrée en Crimée se fait par un isthme étroit qu’ils avaient lourdement fortifié. Mais c’est la loi du nombre qui allait prévaloir, et, après les deux offensives du 28 octobre et du 7 novembre, les Rouges débouchent dans la péninsule. [33]

Wrangel avait déjà soigneusement planifié l’évacuation, et, via une retraite parsemée de combats de retardement, il dirigeait son armée vers divers ports d’où la plupart, en compagnie de milliers de réfugiés, ont pu être évacués vers Istanbul à bord de tout ce qui pouvait flotter. « C’était la démonstration brillante de la capacité de Wrangel à tenir en main les troupes et les civils que cette évacuation qui s’est déroulée, sous la pression des Rouges, avec un minimum de panique et de heurts ». [34] Près de 150 000 personnes ont pu s’échapper, mais malheureusement — tragiquement — des dizaines de milliers sont restées bloquées. Des scènes navrantes se sont déroulées sur les quais alors que leur dernier espoir disparaissait à l’horizon et que les troupes rouges approchaient.

Bela Kun (à gauche), Trotsky (au centre), Frunze (en arrière plan) et Sergei Gusev (à droite)

Les visages de la terreur juive. Pour comprendre le rôle des Juifs à la tête de la Terreur rouge en Crimée, il nous faut examiner les organes de contrôle politique et militaire mis en place par les bolcheviks. L’organe suprême, c’était le Conseil Révolutionnaire-Militaire de la République, dirigé par Trotsky, avec pour adjoint un médecin juif de 27 ans, efficace et fumeur à la chaîne, Ephraim Sklyansky. Bolchevique à partir de 1913, Sklyansky a participé au coup d’État de novembre à Pétrograd où il a attiré l’attention de Trotsky. Trotsky lui déléguait son autorité, lui laissant toute latitude au centre, tandis que lui-même partait en campagne pour conduire la guerre civile. Quand il ne restait plus que la Crimée, Trotsky et Sklyansky ont suivi ensemble cette dernière bataille. Directement subordonné à ce Conseil, on trouvait le Conseil révolutionnaire-militaire (CRM) du Front Sud, c’est lui qui chapeautait l’Armée rouge en Crimée. Sergei Gusev en a été membre sur toute la durée de l’épisode, tandis que Béla Kun en a démissionné pour jouer un rôle plus direct.

Ephraim Sklyansky

Encore en dessous du CMR, on trouvait l’un de ces Comités Révolutionnaires provisoires mis en place pour assurer la transition entre une administration militaire (sur les arrières immédiats du front) et une administration civile. [35] Béla Kun, justement, avait quitté le CMR du Front Sud pour présider le Comité de Crimée, ce qui en faisait l’homme le plus puissant de la péninsule. Il avait pour adjoint un autre Juif,Samuel Davydovich Vulfson. Certaines sources mentionnent Zemliachka comme membre, mais les plus autorisées, non : je suis ces dernières. Le Comité comptait encore quatre membres – non Juifs.

Il y avait deux autres branches du régime actives en Crimée : le Comité du Parti bolchevique de la Crimée et divers détachements de la Tchéka, la très redoutée police secrète. Des cellules spéciales de la Tchéka étaient directement rattachées à l’Armée rouge, on en trouvait jusqu’à l’échelon divisionnaire. Ces cellules avaient des missions de contre-espionnages et de larges prérogatives en matière de répression des activités contre révolutionnaires : elles seront pour une bonne part dans les massacres à venir. Zemliachka était nommée par Lénine à la tête du Comité de Crimée, ce qui en faisait la plus haute responsable politique. Côté Tchéka on trouvait quelques Juifs, dont Semyon Dukelsky et Ivan Danishevsky, mais ils n’étaient finalement pas les plus nombreux.

Jetons un œil à ces hommes.

Béla Kun. C’est la figure que la plupart des sources s’accordent à désigner comme le principal acteur, avec Zemliachka, de ce sinistre épisode. En 1919, sa prestation à la tête de l’éphémère République Soviétique de Hongrie, une dictature juive, lui avait déjà assuré pour l’histoire une postérité d’infamie. [36] Né en 1886 en Transylvanie dans une famille juive de la classe moyenne inférieure, il rejoint le Parti social-démocrate hongrois avant ses dix-sept ans et commence à écrire pour la presse socialiste. Il poursuit des études de droit, mais sans obtenir de diplôme. Durant la guerre, il est lieutenant dans l’armée austro-hongroise, il est fait prisonnier par les Russes en 1916. Dans les camps, il s’abreuve à la propagande bolchevique, se rend à Moscou, rencontre Lénine et fonde la section hongroise du Parti Bolchevique. Il commande une brigade de l’Armée rouge au début de la Guerre Civile avant que Lénine ne l’envoie avec une centaine de « camarades» en Hongrie où il déclenche la révolution de novembre 1918. Le bacille du communisme juif ayant proliféré en Russie, commençait à se propager à l’étranger. À Budapest, il fonde et dirige le Parti Communiste Hongrois, et, en mars 1919, il intègre une coalition de gouvernement Social-Démocrate /Communiste, qu’il dirige de facto si ce n’est de jure. Commissaire aux Affaires Militaires, il impose une collectivisation à marche forcée, nationalisant tous les biens, tentant de créer des fermes collectives … instaurant un régime de terreur rouge et envahissant la Slovaquie. [37] Cette terreur, qui a fait 500 victimes en quelques semaines, était le fait des « Lénine Boys » avec à leur tête l’inévitable Juif de service : Tibor Szamuely. Le gouvernement perdait rapidement tout support domestique et tombe devant une invasion roumaine le 1er août 1919. Kun réussit à s’enfuir en Russie où il devient commissaire politique de division avant de rejoindre le Comité Militaire Révolutionnaire du Front Sud dont nous parlions plus haut. L’envoyé de Lénine allait pouvoir évacuer sa frustration de Hongrie sur le dos de pauvres Gentils sans défense en Crimée.

Bela Kun-Kohn

Il parvenait à inspirer un dégoût viscéral à Angelica Balabanoff, pourtant elle-même une révolutionnaire juive de classe internationale.

J’avais tellement entendu parler de ses antécédents personnels et politiques douteux, que j’ai été surprise . . . d’apprendre qu’il avait été envoyé en Hongrie pour y faire la révolution. Le simple fait qu’il avait une réputation de drogué me paraissait suffisant pour lui barrer toute responsabilité révolutionnaire. Cette première rencontre avait confirmé mes pires appréhensions. Son apparence même était repoussante. [38]

Victor Serge, autre vétéran de la révolution à avoir beaucoup écrit sur le mouvement, disait de lui qu’il était une personnalité particulièrement odieuse, le type même de l’intellectuellement inapte, irrémédiablement affecté d’un manque de clairvoyance militant, mêlé à un autoritarisme de détraqué mental. [39] Serge rapporte une réunion au cours de laquelle un Lénine furieux de la révolution avortée de 1921, en Allemagne, en rendait responsable Kun, le traitant à plusieurs reprises d’imbécile devant tout le monde. [40] Un imbécile, semble-t-il, bien utile dans les massacres.

Samuel Vulfson. Né en 1879 dans la province de Vilna, il a une formation d’ingénieur chimiste. Au tournant du siècle, il rejoint le mouvement révolutionnaire et adhère presque aussitôt à l’aile léniniste. En Russie, il travaille des années durant dans la clandestinité, écrit, organise, subit l’arrestation et l’exil. Il se met un temps en retrait, mais la révolution de février le galvanise et il reprend du service à Moscou où il aurait collaboré avec Zemliachka. Il sévit en Crimée dès la première phase de l’occupation communiste, réquisitionnant la nourriture en tant que commissaire régional de l’alimentation et du commerce (1919), avant que les Blancs n’expulsent les bolcheviks. Avec la chute de Wrangel, il revient aux côtés de Kun au Comité révolutionnaire et de Zemliachka au Comité du Parti. [41]

Sergei Gusev. Né Yakov Davidovich Drabkin en 1874, c’était une figure bolchevique de premier plan. Il rejoint le mouvement en 1896 à Saint-Pétersbourg, c’est un proche de Lénine. Il croise souvent la route de Zemliachka, la première fois lors du Second Congrès du POSDR en 1903, puis, pour une collaboration régulière à Saint-Pétersbourg et Moscou. Lors de la prise du pouvoir, il était secrétaire du premier comité militaire révolutionnaire de Petrograd, celui à l’origine du coup d’État de novembre. [42] Sa fille Elizaveta était la secrétaire de l’éminent Yakov Sverdlov (Yankel Solomon), Président du Comité Exécutif Central (chef de l’État) jusqu’à sa mort en mars 1919. [43] Un historien hongrois, Georgy Borsanyi, porte sur Gusev un avis favorable : « un intellectuel bolchevik qui avait visité les bibliothèques et les musées d’Europe occidentale, parlait plusieurs langues et avait sa propre opinion sur les questions théoriques et pratiques de la révolution. Il était un chef militaire né, tout comme Kun ». [44] Victor Serge, à l’inverse, écrit: « J’ai entendu Gusev s’exprimer dans les meetings. Grand, légèrement chauve et bien bâti, il tentait d’accaparer l’audience en exerçant sur elle l’hypnotisme un peu vil et facile de la violence systématique. Mais pour faire ça, il faut avoir le charisme et être prêt à ne reculer devant rien … Pas un mot de ses propres convictions ». [45] À l’été 1920, Gusev est nommé au Conseil révolutionnaire-militaire de la République aux côtés de Trotsky et de Sklianski, puis il rejoint le Conseil révolutionnaire-militaire du front du sud, poste à partir duquel il jouerait un rôle dans la tragédie de Crimée, dirigeant l’Armée Rouge dans la conquête et l’occupation de la péninsule. [46]

Sergei Gusev-Drabkin

Semyon Dukelsky. Né en 1892 dans la province de Kherson, il est un membre proéminent de la Tchéka en Crimée à l’automne 1920. Il étudie la musique et joue du piano dans les salles de diverses villes ukrainiennes. Il sert dans l’armée tsariste pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, apparemment en tant que musicien, et rejoint les bolcheviks après la Révolution de février. [47] Malgré un manque de compétences militaires, ses supérieurs l’avaient affecté à l’administration de l’Armée rouge ; Sklyansky, écœuré, n’a pas tardé à s’en débarrasser. D’après certaines sources, il aurait été parachuté, «chef de la Tchéka » en Crimée, mais les diverses cellules de la péninsule n’ont été centralisées qu’au printemps 1921. Une source plus détaillée indique qu’il a servi comme chef ou chef adjoint du département spécial du Front Sud. [48] Ce poste était de nature à lui permettre de contrôler les opérations spéciales de toute la Crimée, mais je n’ai trouvé aucun rapport sur ses activités de l’époque.

Semyon Dukelsky

Ivan Danishevsky. Né en 1897, c’était encore un tchékiste juif haut gradé. Il rejoint le Parti Socialiste Révolutionnaire en 1916. Il se jette dans l’action au moment de la Révolution de février, participant à la création d’une section de Gardes Rouges à Kharkov et combattant à divers titres en Ukraine. Il intègre le Parti bolchevique et la Tchéka en octobre 1919, jouant divers rôles dans le gouvernement communiste d’Ukraine. En septembre 1920, il devient chef du département spécial de la treizième armée, celle qui occupe la Crimée après l’évacuation de l’Armée Blanche. Il était donc le chef de l’une des principales forces responsables des exécutions, et cette fois, nous avons des détails sur le rôle qu’il a joué. Il n’avait que vingt-trois ans. [49]

Donald Rayfield, auteur de Stalin and His Hangmen, cite encore deux Juifs impliqués dans les massacres : Lev Mekhlis, commissaire politique dans l’Armée rouge et ami de Zemliachka, et le Tchékiste de seize ans, Alexander Radzivilovski (prénom Israël), qui est né en 1904 à Simferopol, la capitale de la Crimée. Rayfield ne détaille pas leurs actions, disant simplement que Radvasilovski y a commencé sa carrière et que Mekhlis « a aidé Rozalia Zemliachka à l’exécution des officiers blancs faits prisonniers en Crimée ». [50]

Lev Zakharovich Mekhlis Né en 1889 à Odessa, il a travaillé jeune homme comme enseignant et commis. Après une éruption de violence antisémite à Odessa en octobre 1905, il incorpore une unité d’autodéfense, puis le Poale Zion, un parti révolutionnaire sioniste. Durant la Première Guerre, il est enrôlé dans l’armée tsariste. Après la Révolution, il déserte et rejoint les Bolcheviks; il devient commissaire politique de l’Armée Rouge – une bonne place quand on peut l’avoir — c’est là qu’il travaille avec Kun. [51]

En passant, Donald Rayfield déclare que Zemliachka était la maîtresse de Kun à l’époque, sans donner de source. [52] Kun avait épousé en 1913 une hongroise, Iren Gal, le couple avait deux enfants, le deuxième né au début de 1920.[53 ]Cependant, après sa fuite lors de l’effondrement de sa « République soviétique de Hongrie», il a été séparé de sa famille, qui ne l’a rejoint en Russie qu’à l’automne 1921. [54]

D’autres Juifs ont joué un rôle dans ces événements – la plupart oubliés de l’Histoire ou cachés dans des archives – mais quelques-uns ont fait surface : Moisey Lisovsky, N. Margolin et Israël Dagin. Nous avons quelques informations sur les actions de Lisovsky et Margolin, mais rien pour Dagin. Pour Mekhlis, Radzilovski et Dagin, je n’ai rien trouvé de plus que des déclarations selon lesquelles ils étaient « impliqués ». De deux autres, Dukelsky et Vulfson, nous connaissons les postes qu’ils ont occupés mais n’avons aucun détail relatifs à leurs actions. Voici une liste des Juifs qui ont joué un certain rôle, approximativement classés par ordre d’importance :

Trotsky : Commissaire à la guerre, chef de toutes les forces armées

Sklyansky : Le puissant adjoint de Trotsky

Gusev : membre du CMR Front Sud, supervise l’Armée Rouge en Crimée

Kun : Président du Comité révolutionnaire de Crimée, plus haut fonctionnaire de la région

Vulfson : membre du Comité révolutionnaire de Crimée et du Comité du Parti

Zemliachka : chef du Comité du Parti bolchevique en Crimée

Dukelsky : figure majeure dans la Tchéka

Danishevsky : figure majeure de la Tchéka, des milliers d’exécutions à son compte

Mekhlis : commissaire politique ; actions spécifiques inconnues

Lisovsky : commissaire politique 9e division de fusiliers ; organise des exécutions.

Dagin : Officier de la Tchéka ; actions spécifiques inconnues

Radzivilovski : Officier de la Tchéka ; actions spécifiques inconnues

Margolin : commissaire, a menacé les Blancs de « l’épée impitoyable de la Terreur rouge »

Ce noyau est auréolé d’une réputation méritée de brutalité immonde. Les qualificatifs qui lui sont appliqués par les historiens ou ceux qui ont connu ses membres varient de « atroce », « odieux », « scorpion vicieux », « légendaire par sa cruauté », « sadique », « arrogant », « crétin » à « monstre». Et ce groupe n’était qu’un parmi des douzaines – voire des centaines – similairement composés d’une direction exclusivement ou majoritairement juive, qui ont écumé la Russie de long en large pendant plus de tente ans.

Israël Radzilovski Tchékiste

Lev Mekhlis, sioniste converti bourreau stalinien

Traîtrise Juive: La Fausse Promesse d’Amnistie Avant que Wrangel n’ait achevé son évacuation, Sklyansky avait tendu un piège aux officiers blancs, leur offrant une fausse amnistie afin d’en capturer et d’en tuer le plus possible. Il s’est servi du prestige du général Alexei Brusilov comme appât. Brusilov, l’un des meilleurs généraux russes de la Première Guerre mondiale, était passé chez les bolcheviks, convaincu qu’il était que le régime de Lénine ne tiendrait pas longtemps. Brusilov

avait été approché par Sklyansky . . . qui avançait l’idée qu’un grand nombre d’officiers ne voulaient pas quitter la Russie et pourraient être persuadés de faire défection si Brusilov apposait son nom au bas d’une déclaration leur offrant une amnistie. Sklyansky lui faisait miroiter le commandement d’une nouvelle armée de Crimée formée à partir des restes des forces de Wrangel. Brusilov était séduit par l’idée d’une armée purement russe composée d’officiers patriotes … qui lui permettrait éventuellement de … le moment voulu … disons, dans premier temps, de sauver la vie de beaucoup. Il accepta d’entrer dans ce jeu de dupes. . . Trois jours plus tard, on lui disait que le plan était à l’eau : les officiers de Wrangel, selon Sklyansky, n’avaient finalement exprimé la volonté de faire défection. Brusilov comprit, mais un peu tard, que ce n’était pas vrai. Lors de l’évacuation finale à Sébastopol, les Rouges avaient distribué . . . des milliers de tracts offrant une amnistie au nom de Brusilov. Des centaines d’officiers y avaient cru et sont restés. Ils ont tous été abattus. [55]

Peu après, Sklyansky envoyait un télégramme aux bolcheviks en Crimée, leur enjoignant de poursuivre le massacre : « Que la lutte continue jusqu’à ce qu’il ne reste plus un seul officier blanc vivant sur le sol de Crimée». [56] De son côté, Trotsky faisait savoir à Kun et Zemliachka qu’il ne se rendrait pas en Crimée tant qu’il s’y trouverait encore un « contre-révolutionnaire ». [57] Lénine faisait également connaître son point de vue: «Il faut s’en débarrasser au plus vite . . . sans pitié». [58] Kun et Zemliachka ne pouvaient pas ne pas comprendre ce qu’on attendait d’eux.

Le Massacre Peut Démarrer. Le 17 novembre 1920, l’occupation de la Crimée était complète. La péninsule avait historiquement une population très mélangée ; outre les Russes et les Ukrainiens, il y avait des Tatars (musulmans) turcs, des Allemands, des Grecs et des Arméniens. La population atteignait alors les 800 000 habitants, gonflée par l’afflux des réfugiés politiques et des soldats : environ 50 000 Russes blancs et 200 000 civils. Bela Kun faisait cerner la péninsule et toute la population se retrouvait à sa merci. Les bolcheviques radicaux et la Tchéka investissaient la péninsule, prêts à faire subir les foudres de la Terreur rouge à une population qu’ils détestaient et qu’ils avaient crainte.

Péninsule de Crimée

La première ville traitée a été Simferopol, la capitale, le 12 novembre. Pendant plusieurs jours, des soldats ont saccagé, pillé, violé, fusillé. En une semaine, les unités de l’Armée rouge et de la Tchéka avaient exécuté 1 800 personnes, et en quelques mois, le nombre a dépassé 10 000 dans la ville et ses environs. [59] [FG: on note qu’avec la meilleure volonté du monde, il faut un certain temps pour un massacre, 30 000 en deux jours, ce n’est pas possible] Ils ont procédé par fournées de plusieurs centaines d’officiers et de notables, les entraînant hors de la ville, les forçant à creuser des fosses avant de les abattre. Ils pouvaient aussi se servir des ravins. Le général Danilov, un ancien officier tsariste qui a servi dans la quatrième armée de l’Armée rouge, rapporte que

les alentours de Simferopol étaient empuantis par les cadavres en décomposition . . . qui n’étaient même pas enterrés . . . Les fosses derrière le jardin de Vorontsov et dans le domaine de Krymtaev . . . étaient remplis de cadavres à peine recouverts d’une mince couche de terre . . . Le total de ceux qui ont été fusillés à Simferopol seulement du jour où les Rouges sont entrés en Crimée au 1er avril 1921 atteignait 20 000 . . . [60]

Le 15 novembre, les troupes faisaient route vers Sébastopol « précédées d’une voiture blindée marquée en capitales rouges d’une étoile et de l’inscription « Antéchrist », [61] un diptyque caractéristique des commissaires juifs des premiers jours du règne communiste sur Terre. Le « reliquat des réfugiés se tenaient sur les côtes dans le froid de la bise, lorsque les cavaliers rouges sont apparus au bout de la jetée. Quand ces soldats déguenillés aux pieds nus se sont trouvés en présence de ces gens, ils avaient encore les nerfs à vifs . . . d’avoir subi le crépitement des mitrailleuses. . . . Les troupes . . . ont estimé que cela méritait bien une compensation ». [62] L’auteur ne dit pas en quoi consistait cette « compensation », mais on peut supposer qu’il s’agissait du tarif habituel de la soldatesque. Le viol «avait pris des proportions gigantesques, en particulier dans les . . . régions cosaques de la Crimée en 1920 ». [63]

Les viols ne sont pas restés dans les mémoires à cause de l’échelle monstrueuse des massacres. Selon Sergey Melgunov, un témoin scrupuleux de l’époque, on comptait 8.000 victimes à Sébastopol pour la seule première semaine, les pendaisons étaient monnaie courantes: « La perspective Nakhimovskyt était comme pavoisée de cadavres d’officiers, de soldats et de civils qui, arrêtés au hasard, avaient été exécutés sur place … sans autre forme de procès (témoignage oculaire). [64] Ce n’était pas que sur la perspective Nakhimovskyt que les Rouges avaient pendu leurs victimes, mais partout dans la ville, aux lampadaires, aux poteaux, aux arbres et aux statues. La ville offrait un paysage dantesque, les morts au grand jour, les vivants reclus dans des caves. [65]

Des centaines de malades et de blessés – pas seulement des officiers blancs – ont été sortis des hôpitaux et fusillés. Les infirmières et les médecins y sont passés aussi parce qu’ils avaient soigné des soldats blancs ; les noms de dix-sept infirmières de la Croix-Rouge figurent sur une liste publiée par les bolcheviks. Des centaines de dockers ont été abattus parce qu’ils avaient participé à l’embarquement des hommes de Wrangel. Melgunov estime que les Rouges ont exécuté plus de 20 000 personnes dans la région de Sébastopol. [66] Fin novembre, les autorités de la ville ont publié deux listes de victimes (une pratique occasionnelle de la Tchéka). Ces listes n’ont jamais été données pour complètes, mais rien que celles-ci totalisaient 2 836 noms dont 366 féminins. [67]

À Feodosia, des milliers de soldats Blancs se sont rendus, espérant la clémence:

Après avoir été désarmés, ils ont été nombreux à proposer de rejoindre l’Armée rouge, mais au lieu de ça, des soldats de la 9e division de fusiliers, sous la direction des tchékistes de Nikolaï Bistrih, ont exécuté 420 blessés et réparti le reste dans deux camps de concentration. Comme il s’est avéré, ce n’était que l’acte inaugural d’une campagne de terreur qui devait durer cinq mois. [68]

Le commissaire politique de cette 9e division était un Juif, Moisey Lisovsky. Il a participé à l’action qui vient d’être relatée, ordonnant la fusillade d’une centaine de blessés Blancs à la gare, dans la nuit du 16 novembre. [69] Dieu seul sait combien d’autres il en a fait fusiller dans les mois qui ont suivi, mais on peut s’en faire une idée :

Au départ, on disposait des cadavres en les jetant dans les anciens puits génois ; mais même ces puits ont fini par être pleins, et les condamnés devaient être emmenés hors de la ville. . . . Là on leur faisait creuser des fosses avant que le jour ne faiblisse, on les enfermait dans des hangars une heure ou deux, et, avec la tombée de la nuit, dépouillés de tout à l’exception des petites croix autour de leur cou, ils étaient abattus. À mesure qu’ils étaient abattus, ils tombaient en avant en couches. Et couche après couche, la fosse se remplissait jusqu’à raz-bord. [70]

Beaucoup n’étaient pas tués sur le coup et achevaient d’agoniser enterrés vivants au milieu de cadavres en sang.

À Feodosia, nous trouvons un autre tchékiste juif de haut rang, Ivan Danishevsky. Il dirigeait le département spécial de la 13ème armée, œuvrant à Feodosia et à proximité de Kerch avec une énergie aussi juvénile que démoniaque. En décembre seulement, il a condamné à mort 609 personnes à Kerch et 527 à Feodosia. Les documents existants montrent clairement qu’il était responsable de la mort de plus de 2 000 personnes. Pour le 27 novembre, il rapportait que « 273 prisonniers ont été exécutés dans la journée, dont : 5 généraux, 51 colonels, 10 lieutenant-colonels, 17 capitaines, 23 capitaines d’état-major, 43 lieutenants, 84 sous-lieutenants, 24 fonctionnaires, 12 officiers de police, 4 huissiers ».[71]

À Kertch (et ailleurs), les communistes ont chargé des gens sur des barges, les ont emmenés au large et les ont coulés. Certains accusent Zemliachka d’avoir voulu économiser les balles. C’était une « technique » de la Révolution française qui avait été adoptée par la Tchéka et qui avait été précédemment mise en œuvre, par exemple, par la juive à moitié folle, Rebecca Plastinina-Maizel dans le Grand Nord. [72] (Ce qui ne l’a pas empêché de siéger à la Cour suprême de l’Union soviétique). [73]

Le chef de la Tchéka à Kertch était un certain Joseph Kaminsky [FG : un peu comme Jacques l’éventreur qui s’appelait Aaron Kosminski]. Le nom Kaminsky est courant chez les Russes et les Juifs. Parmi les autres bourreaux à Feodosia/Kerch figurent Zotov, N. Dobrodnitsky, Vronsky, Ostrovsky et I. Shmelev, certains pourraient bien être juifs. [74]

Recensement en vue d’extermination

Au bout de quelques jours, Kun a ordonné aux résidents de Crimée de s’inscrire auprès des autorités. Tous les adultes ont été sommés, sous peine de mort, de

se présenter à la Tchéka locale pour remplir un questionnaire contenant une cinquantaine de questions sur leurs origines sociales, leurs actions passées, leurs revenus et aussi sur leurs . . . opinions au sujet de . . . Wrangel et des Bolcheviks. Sur la base de ces enquêtes, la population a été divisée en trois groupes : ceux à abattre, ceux à envoyer dans des camps de concentration et ceux à épargner. [75]

Le principe d’action, en l’occurrence, avait déjà été énoncé par Martin Latsis, membre de l’organe dirigeant de la Tchéka (le Collège), en novembre 1918 :

Nous sommes là pour détruire la bourgeoisie en tant que classe. Par conséquent, chaque fois qu’un bourgeois nous passe entre les mains, la première chose à faire doit être, non . . . de découvrir des preuves matérielles d’un crime . . . mais de poser au témoin les trois questions : « À quelle classe appartient l’accusé ? » « Quelle est son origine ? » et « Décrivez son éducation, sa formation et sa profession.» C’est uniquement en fonction des réponses à ces trois questions que son sort devra être décidé. Car c’est la raison d’être de la « Terreur rouge ». [76]

On peut se rendre compte des résultats du recensement effectué par les hommes de la 9e Division de fusiliers à Feodosia : « 1100 personnes recensées , 1006 abattues, 79 emprisonnées et seulement 15 libérées». [77] Moisey Lisovsky, le commissaire politique de la division, a certainement joué un rôle dans ce massacre. À Kertch, des patrouilles de la Tchéka ont bouclé la ville pour le recensement, identifié 800 ennemis de classe et les ont abattues. Les habitants pensent que le nombre est beaucoup plus élevé. [78] À Sébastopol, la Tchéka avait transformé un quartier en camp de transit et y avait filtré la population recensée, les heureux élus étant ensuite fusillés hors de la ville, comme on l’a vu plus haut. [79] Dans les principales villes de la Crimée, les Rouges ont procédé à des exécutions de masse suite à ce genre de recensement. Il est apparu que toutes ces éxécutions étaient le fruit d’un ordre direct contresigné par Kun et Zemliachka. [80]

Zemliachka le Démon – L’écrivain russe Ivan Shmelev, qui a personnellement souffert de ces événements – les communistes ayant abattu son fils, lieutenant Blanc – a écrit en souvenir un livre poignant : Le Soleil des morts. Devant le tribunal de Lausanne en 1923, il dresse, par petites touches impressionnistes, un portrait de Zemliachka:

Elle volait de clocher en clocher, cintrée dans son éternelle veste de cuir, son visage était d’une pâleur maladive, sa bouche sans lèvres, ses yeux éteints ; . . . la silhouette menue, le Mauser énorme . . . c’était son heure de gloire. Là, Zemlyachka-Zalkind n’avait pas son pareil. . . . « Feu, Feu, Feu … » répétait-elle sans arrêt, jouissant d’assouvir enfin ses instincts meurtriers si longtemps refrénés. . . . Rozalia Samuilovna s’est montrée en Crimée comme le chien le plus loyal, la voix de son maître, Lénine. Elle n’escomptait aucune récompense, la chair et le sang suffisaient à la combler. Son épopée laissait derrière elle, sur les montagnes et sur la mer, un sillage rouge de sang. [81]

Ce portrait démoniaque trouve un écho chez un haut responsable bolchevik envoyé en Crimée au printemps 1921 pour se rendre compte de la situation. Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev, un responsable du Parti communiste musulman, déclarait ainsi à propos de Zemliachka :

La camarade Samoylova (Zemlyachka) était une femme d’une irritabilité et d’une intransigeance extrême, qui rejetait a priori toute idée d’agir par la persuasion . . . . Un état d’énervement permanent, toujours à hausser le ton avec presque tous les camarades, des exigences extravagantes . . . des répliques coupantes dès qu’on s’avisait d’avoir la témérité d’exprimer une opinion personnelle . . . Quand la camarade Samoylova était en Crimée, littéralement tous les travailleurs tremblaient devant elle, n’osant pas désobéir même aux ordres les plus stupides ou erronés. [82]

Je me suis abstenu de reprendre les descriptions les plus pittoresques de Zemliachka parce qu’elles manquent de sources solides, mais ces deux récits donnent une indication de sa folie homicide. Certains auteurs disent qu’elle a manié les mitrailleuses, torturé des prisonniers ou eu des accès de rage. Peut-être. Une écrivaine moderne russo-juive, Arkady Vaksberg, qui en sait long sur ces Juifs communistes, dit d’elle que c’est « un monstre sadique », sans détails, malheureusement. [83] Nous ne pouvons qu’attendre un travail plus approfondi dans les archives soviétiques.

Pendant ce temps, le massacre se poursuivait, le 5 décembre, un certain N. Margolin publiait un article dans le journal Krasny Krim (« La Crimée rouge ») :

L’épée impitoyable de la Terreur rouge pourfendra toute la Crimée et nous la purifierons de tous les bourreaux et exploiteurs de la classe ouvrière. Mais nous serons plus malins et ne répéterons pas les erreurs du passé ! Nous avons été trop gentils après la révolution d’octobre. L’expérience a été amère, mais cette fois, nous ne serons plus aussi magnanimes. [84]

Il traite les victimes de ce grand massacre de bourreaux ! Était-ce le même N. Margolin que celui que Soljenitsyne nous décrivait en affameur, en commissaire juif impitoyable, célèbre pour avoir fouetté les paysans qui ne fournissaient pas de grain. (Et qui les assassinait par-dessus le marché) ? [85] Ça doit être lui.

La tuerie a duré jusqu’au printemps suivant. En outre, des dizaines de milliers de personnes ont été internées dans des camps de concentration de fortune, avant d’être redirigés vers des camps plus grands hors de Crimée. 50 000 Tatars musulmans ont été expulsés en Turquie ou expédiés dans des camps en Russie. Il y a eu des rapports selon lesquels 37 000 hommes de l’armée de Wrangel languissaient dans des conditions épouvantables dans des camps de la région de Kharkov. [86] Vu ces conditions, il est à craindre que beaucoup de ces hommes soient morts. Lorsque la Tchéka a envoyé une requête à Lénine demandant ce qui pouvait être fait pour améliorer la situation dans les camps, il s’est contenté de noter sur le papier, « aux archives ». [87]

Rappel de Kun et de Zemliachka – Après un mois de cette orgie sanguinaire, les tensions accumulées éclataient au grand jour parmi les tortionnaires. Certains commençaient à exprimer des doutes et des craintes devant cette violence qui proliférait à une allure vertigineuse, au point de menacer de prendre une dynamique propre, totalement indépendante de tout contrôle. Les signes d’indiscipline se multipliaient, avec les escadrons de la mort qui se livraient à toutes les exactions, se livraient au pillage, montaient des harems, tuaient pour des raisons personnelles. On s’inquiétait aussi du degré de fanatisme de Zemliachka et de Kun qui liquidaient toute la classe moyenne, y compris les experts et techniciens dont les bolcheviks auraient besoin pour faire fonctionner la péninsule après la normalisation. L’un des membres du Comité révolutionnaire, Youri Gaven, qui n’était pas Juif, écrivait une lettre à un ami du Comité central à Moscou le 14 décembre, disant que Kun était devenu une sorte de Moloch et que sa place était à l’asile. Gaven, se défendant par avance de toute faiblesse, prenait soin de préciser qu’il était lui-même pour la terreur, mais que trop de personnes utiles étaient tuées. [88] Le même jour, Zemliachka se fendait d’une longue lettre à Moscou, se plaignant des faiblesses et défaillances de certains cadres, qui, disait-elle, la forçaient à faire tout le travail. [89] (Des lettres du même genre, elle en envoyait déjà à Lénine dès 1904. [90]) Elle demandait le rappel à Moscou d’un certain nombre de responsables, dont pas un n’était juif (y compris le frère cadet de Lénine, Dmitry Ulyanov, qui siégeait au comité du parti de Crimée). Il y aurait donc eu une composante ethnique à cette controverse, les non-Juifs prônant une certaine modération, les Juifs étant partisans de la terreur maximale. En l’occurrence, Moscou répondait en rappelant Zemliachka et Kun, début janvier 1921. Ils n’étaient en Crimée que depuis sept semaines.

Zemliachka et Kun ne sont donc pas responsables de la totalité des 50 000 morts, cependant, les sources semblent indiquer que la plupart des décès ont eu lieu alors qu’ils étaient en Crimée. Rien n’indique que Lénine ait réprimandé les deux fous furieux, ni même qu’ils soient tombés en disgrâce. Au contraire Zemliachka était nommée au Comité du Parti à Moscou et Kun au présidium du Komintern. Zemliachka se voyait décerner le drapeau rouge pour son service exemplaire pendant la guerre civile. [91])

On trouve dans l’Encyclopédie juive universelle, publiée à New York dans les années 1940, une notice des activités de Zemliachka pendant la guerre civile. Zemliachka, disait-on, « s’est rendue utile au front.» Un bel exemple d’historiographie juive à encadrer.

Épilogue

Après son arrivée à Constantinople, Wrangel s’est efforcé de maintenir l’ordre et l’unité parmi les exilés. En 1924, il fonde l’Union militaire panrusse pour maintenir l’espoir d’un renversement du régime communiste. En 1927, il déménage à Bruxelles avec sa famille, quasiment réduit à la pauvreté. Il écrit ses mémoires, Always with Honor, qui sont publiées après sa mort. Sa brusque disparition en avril 1928 alimente aussitôt des soupçons d’empoisonnement par des agents bolcheviques. Les deux hommes qui lui ont succédé à la tête de l’Union militaire, les généraux Kutepov et Miller sont eux-mêmes enlevés et tués. [92] Les restes de Wrangel se trouvent à l’église de la Sainte Trinité à Belgrade.

En Crimée, bien que les communistes aient déjà assuré leur emprise, les exécutions se sont poursuivies jusqu’au printemps. D’autres Juifs sont arrivés ; Alexandre Rotenberg prenait le commandement de la Tchéka de la Crimée normalisée en septembre 1921. [93] La famine, qui va souvent de pair avec la domination bolchevique, prenait le relais des massacres. Mirsaid Sultan-Galiev mentionné ci-dessus rapportait au Comité central en avril 1921 :

La situation alimentaire empire chaque jour. Tout le district sud, habité principalement par la population tatare, est littéralement affamé au moment où je vous parle. Le pain n’est distribué qu’aux employés soviétiques, et le reste de la population . . . ne reçoit rien. Des cas de famine sont observés dans les villages tatars. . . . À la conférence régionale. Les délégués tatares ont indiqué que les enfants « tombent comme des mouches ». [94]

La situation en Crimée était catastrophique, mais la principale cause de la famine, qui a tué environ 100 000 personnes, n’était autre que la gestion bolchevique, en particulier la réquisition de nourriture et la collectivisation des terres, avec la création des fermes d’État totalement inefficaces. En mars 1922, la Tchéka de Crimée rapportait que le cannibalisme « devient courant ». Pendant ce temps, des enfants disparaissaient, et « à Karasubazar en avril 1922, un entrepôt contenant 17 cadavres salés, principalement des enfants, était découvert ». [95] Ce n’est qu’en 1923 qu’une certaine normalité est revenue – la normalité toute relative qu’on peut escompter d’un régime communiste.

La prise de contrôle de la Crimée par les Rouges a été un horrible bain de sang qui a plongé la population dans un état de choc et d’horreur et inspiré une haine tenace du régime bolchevique. Une grande partie de la population est passée du côté des Allemands pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, ce qui a déclenché une nouvelle répression et des vagues de déportation lorsque les forces de Staline ont repris la région au printemps 1944.

Passons maintenant à la vie d’après des sanguinaires.

Je n’ai trouvé aucune autre information sur Lisovsky et Margolin. [96]

Alexandre-Israël Radzilovski, le tueur adolescent, a eu une longue carrière dans la Tcheka puis au NKVD, atteignant le grade de major principal de la sécurité d’État (un grade équivalent à celui de général d’armée) et de chef adjoint du NKVD de Moscou, de 1935 à 1937. En 1936, il est député au Soviet suprême, la plus haute instance du régime. Il reçoit l’Ordre de Lénine en 1937, peu avant d’accompagner Lazar Kaganovich à Ivanovo, pour une nouvelle Grande Terreur : « La tornade noire ». [97] (Ici du moins, les victimes étaient communistes) Il est arrêté en septembre 1938, accusé d’espionnage au profit de la Pologne et fusillé en janvier 1940. [98]

Israel Dagin a également poursuivi une longue carrière à la Tchéka et dans les organes de répression. Il atteint un rang encore plus élevé que Radzivanski, commissaire de la sécurité d’État de grade 3, équivalent à commandant de corps. Il a travaillé dans de nombreuses villes, arrêtant, purgeant, tuant – la routine des officiers Tchéka. En 1937, au plus fort de la Grande Terreur,

Dagin et ses hommes devaient . . . . superviser l’une des opérations de terreur de masse les plus notoires. Le 28 juillet 1937, E. G. Evdokimov réunit les dirigeants locaux du Parti [dans le Caucase] et donne des instructions pour la purge massive prévue de longue date. Dagin, en étroite collaboration, a mené l’opération de police proprement dite. . . . Dagin avait depuis longtemps élaboré un plan, avec des listes de noms dans chaque localité. [99]

Rien que dans la première de ces petites régions, la Tchechnie-Ingouchie, « 5 000 prisonniers étaient entassés dans les prisons du N.K.V.D. à Grozny, 5 000 dans le garage principal du Grozny Oil Trust, et des milliers d’autres dans divers . . . bâtiments. Au total, environ 14 000 arrestations, soit environ 3 % de la population. [100] Toutes ces personnes ont été ou fusillées ou envoyées dans des camps. Mêmes auteurs, mêmes tragédies, seules les victimes changent. Dagin a reçu les plus hautes décorations d’État, mais il était également arrêté en novembre 1938 et abattu quelques jours avant Radzizilovski. [101]

Lev Mekhlis a connu une longue carrière sous Staline en tant que secrétaire personnel, rédacteur en chef de la Pravda, député du Soviet suprême et membre du Comité central. (Le Comité central était l’organe dirigeant du Parti communiste ; le Politburo, l’Orgburo et le Secrétariat étaient techniquement des sous-départements en son sein). Il a dirigé diverses purges sur l’ordre de Staline, inspirant la terreur surtout chez les officiers. En 1937, Staline le nomma chef de la direction politique principale de l’armée (le faisant commissaire politique pour toute l’armée), fonction qui lui permit de mener à bien la fameuse grande purge de l’Armée rouge. Il « était capable de trouver des ennemis partout » et aura joué un grand rôle dans les répressions politiques de cette période. [102] Durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Mekhlis a parcouru des milliers de kilomètres sur les fronts, tuant autant de généraux de l’Armée rouge que les Allemands. Sa cruauté était légendaire . . . [103] En septembre 1940, il croisa à nouveau le chemin de son amie Zemliachka et lui succéda comme ministre du contrôle d’État, un organe de surveillance placé au-dessus des bureaux du Parti et du gouvernement. On peut fidèlement résumer Mekhlis en remarquant qu’il était à la fois le serviteur indéfectible de Staline et l’ami cher de Rozalia Zemliachka, deux des personnages les plus maléfiques du vingtième siècle. Mekhlis a pris sa retraite en 1950, titulaire des plus hautes distinctions, et est mort de causes naturelles en février 1953, moins d’un mois avant la mort de son maître, Staline.

Ivan Danishevsky, le juvénile bourreau de la Tchéka, reçut une montre en or pour son « travail » en Crimée. Dans les quelques mois qui suivirent, il fut envoyé dans le Caucase pour une mission similaire, liquidant des personnalités intelligentes et dignes d’intérêt – les ennemies naturelles du régime bolchevique – dans une région nouvellement conquise par les forces rouges. Avant la fin de 1921, le Parti l’affecte à un travail civil dans le commerce et la finance. Dans les années 1930, il est ingénieur, travaillant à des moteurs d’avion à la tête d’une grande usine (les usines industrielles soviétiques étaient gigantesques). Pendant la Grande Terreur, il échappe de justesse à une arrestation en dénonçant parmi son entourage, il est finalement arrêté à son tour en août 1938. Torturé, il avoue de fausses accusations et est condamné à mort. Inexplicablement, il est épargné et envoyé dans les mines d’or de Kolyma où il survit jusqu’en 1955, date à laquelle il est libéré et autorisé à rentrer à Moscou. Il écrit un certain nombre d’ouvrages sur l’histoire soviétique dans lesquels il défend énergiquement la pure doctrine communiste. [104] Il meurt en 1979.

Quant à Semyon Dukelsky, le musicien tueur de la Tchéka, il quittait bientôt la Crimée pour prendre le commandement de la Tchéka à Odessa, remplaçant le juif Max Deich, qui s’était acquis une « réputation de sadique drogué » et avait dû être rappelé. [105] Il a travaillé à divers postes de la Tchéka et du gouvernement – plusieurs fois muté ou réprimandé pour incompétence – en 1938, le Politburo essaiera de le caser responsable du Département cinématographique du Comité central ; son prédécesseur, le juif Boris Shumiatsky, ayant été fusillé. Ceux qui ont travaillé sous lui en gardent un très mauvais souvenir : rigide, excentrique, doctrinaire, arrogant. Mais là encore, il ne tient qu’un an. De 1939 à février 1942, il est commissaire de la marine de guerre (ou de la marine marchande ; les sources ne sont pas claires); puis, jusqu’à sa retraite en 1952, il est vice-commissaire/ministre de la justice. Il se met à émettre des dénonciations de plus en plus invraisemblables, à tel point qu’il est interné en asile psychiatrique. Il meurt en 1960. [106]

Samuel Vulfson, collaborateur de Kun au sein du Comité révolutionnaire de Crimée, est retourné à Moscou en 1921. Il a siégé au comité du parti de Moscou (avec Zemliachka) et, après 1924, il a travaillé dans le commissariat du commerce extérieur et en tant que représentant commercial en Europe occidentale. En 1929, sa tuberculose s’aggravant, il part à l’étranger et décède à Berlin en 1932. [107]

Sergei Gusev – Drabkin a continué à travailler dans l’administration politique de l’Armée rouge, pendant un certain temps en tant que chef du département, avant que Trotsky ne le fasse partir – Gusev était l’homme de Staline. Gusev a ensuite travaillé dans le Parti en tant que membre aspirant du Comité central et secrétaire de la Commission centrale de contrôle (1923), qui était l’organe disciplinaire placé au-dessus du Parti et du gouvernement. Au milieu des années 1920, Staline l’affecte au Komintern, ce qui lui donne l’occasion de se rendre aux États-Unis pour arbitrer un différend au sein du Parti communiste américain, sous le nom de « P. Green ». Gusev participe à la controverse sur la littérature en Russie, arguant (avec Zemliachka et d’autres partisans de la ligne dure) que les écrivains doivent se contenter de propager la pure doctrine communiste, sans égards à leur liberté littéraire. Dans un discours prononcé au quatorzième Congrès du Parti en décembre 1925, il dit : « Lénine nous enseignait que chaque membre du Parti devait être un agent de la Tchéka – c’est-à-dire qu’il devait surveiller et informer », et il concluait que « si nous souffrons d’une chose, c’est bien de ne pas le faire assez ». [108]. Ça fait froid dans le dos. Le principal défenseur de la liberté de création, l’écrivain Alexander Voronsky, tombait en disgrâce et fut fusillé en 1937. Gusev a continué à travailler à des postes élevés du Komintern jusqu’à sa mort en 1933. [109]

Ephraim Sklyansky, le jeune assistant de Trotsky qui avait berné des milliers d’officiers blancs avec une fausse promesse d’amnistie, n’a pas survécu longtemps. En avril 1924, il perdait son poste au sein du Conseil révolutionnaire-militaire à cause de l’hostilité de Staline, qu’il avait fortement critiqué pendant la guerre civile. Il a été muté dans la sphère économique, à la tête d’un conglomérat textile. En 1925, il se rend en Europe et en Amérique pour récolter des informations sur la production industrielle, mais se noie dans un accident de bateau suspect. Arkady Vaksberg, entre autres, accuse Staline:

Sklyansky a été noyé dans un lac lors d’un voyage d’affaires aux États-Unis avec le directeur d’Amtorg (la société de commerce américano-soviétique), Isaïe Khurgin. . . Le meurtre de deux juifs que Staline détestait avait été organisé par deux autres juifs, Kanner et Yagoda. [110]

Grigory Kanner était l’un des secrétaires de Staline ; Genrikh Yagoda était à cette époque chef de de facto l’OGPU, l’organe qui succédait à la Tchéka. Un historien note que Kanner « était chargé des sales coups de Staline contre Trotsky et d’autres », [111] mais il n’y a pas de preuve tangible de la culpabilité de Staline; l’accusation émanait à l’origine de Boris Bazhanov, ancien secrétaire de Staline.

Bela Kun, qui était virtuellement dictateur en Crimée au moment du massacre, est parti directement au Présidium du Komintern (qui était dirigé par Grigori Zinoviev jusqu’à la fin de 1926). Lénine l’a ensuite envoyé, en tant qu’agent du Komintern, en Allemagne, en compagnie d’un autre Juif hongrois, Joseph Pogany (de son vrai nom Schwarz), pour y déclencher la révolution communiste. Les attentes étaient élevées ; Lénine avait toujours considéré que le succès de la révolution en Russie dépendait de l’adhésion de l’Allemagne à la révolution mondiale. Imaginez cette terrifiante perspective : l’association d’une Russie et d’une Allemagne communiste ! Le résultat fut l’Action de mars, un soulèvement très mal préparé qui a rapidement tourné au fiasco. Kun, éreinté par Lénine, est envoyé dans l’Oural, affecté au comité local du Parti, sans toutefois perdre sa place au Komintern. Dans les années 1920, il travaillait sous couverture en tant qu’agent du Komintern en Allemagne, en Autriche et en Tchécoslovaquie, jusqu’à son arrestation à Vienne en 1928, après quoi il est resté en Union soviétique, dirigeant toujours le Parti communiste hongrois en exil. Il a continué à travailler dans les échelons supérieurs du Komintern jusqu’au milieu des années 1930. [112] En juin 1937, c’est son tour d’être dénoncé et arrêté. Ses tortionnaires du NKVD, probablement des voyous juifs, l’ont battu et forcé à rester debout sur un pied pendant près de vingt heures ; quand « il est retourné dans sa cellule après l’interrogatoire, ses jambes étaient gonflées et son visage était si noir qu’il en était méconnaissable ». [113] Il est abattu en août 1938, avec pratiquement tout le contingent d’émigrés communistes hongrois.

Rozalia Zemliachka. Elle avait quarante-quatre ans en 1920, elle a vécu encore vingt-sept ans, servant à des postes variés de la machine soviétique. Stalinienne naturelle, elle était immunisée contre les arrestations – en fait, c’est elle qui purgeait. Elle « avait toujours été le genre de bolchevik qui plaisait à Staline parce qu’elle partageait sa vision manichéenne du monde, un lieu d’affrontement à la mort entre alliés et ennemis ». [114]

Après « s’être rendue utile» en Crimée, elle rentre à Moscou en janvier 1921, travaillant comme secrétaire de l’un des comités du parti du district. Dans les années suivantes, elle travaille dans l’Oural et le Caucase du Nord comme « responsable de la formation, des manuels, des conférences et des cours à destination des ouvriers ». [115] Elle travaillait pour Staline, le soutenant contre l’opposition, que ce soit Trotsky ou Kamenev et Zinoviev. En 1926, Staline la nomme membre du conseil d’administration de la Commission centrale de contrôle, ce qui signifiait qu’elle avait atteint le rang de principale responsable de la discipline du parti. C’est un rôle qu’elle continuera à jouer pour le reste de sa carrière [116 ], ce qui l’a amené à travailler pour le NKVD:

Il ne fait aucun doute que Zemliachka ait travaillé en étroite collaboration avec le NKVD. Ses fonctions exigeaient qu’elle leur transmette ses rapports et dossier, de plus, il est probable qu’elle était pleinement prédisposée à le faire. . . . Convaincue de l’existence de complots menaçants pour le Parti, elle est devenue experte pour les contrecarrer. Elle a également réussi à se protéger des purges qui ont balayé les rangs du NKVD lui-même. . . . Au lieu d’être victime, Zemliachka collectionnait les distinctions. En septembre 1936, elle recevait la plus haute décoration civile soviétique, l’Ordre de Lénine. [117]

En 1937, elle devient députée du Soviet suprême et, deux ans plus tard, membre du Comité central. La même année, elle devient vice-présidente de la Commission de contrôle et vice-présidente du Conseil des commissaires du peuple (poste équivalent à celui de vice-premier ministre). Elle est très proche du sommet. Elle passe les années de guerre à Moscou, rédigeant des souvenirs polémiques sur Lénine et effectuant diverses tâches mineures. Elle prend sa retraite en 1943 et décède à l’âge de soixante-dix ans, en janvier 1947.

La Russie qui existait à sa naissance n’était plus. D’une Terre fertile, de paix, d’ordre et de développement sous l’égide de sa petite communauté allemande, [118] la Russie avait basculé, sous la coupe de sa minorité juive, dans la peur, le meurtre, la dénonciation et les camps de concentration. Zemliachka est la figure de proue de cette transformation, l’incarnation de la haine juive au pouvoir et de son zèle pervers.

Zemliachka qui préside un procès de la Grande Purge

Conclusion

La question se pose de savoir combien d’autres victimes ces Juifs ont-ils faits après la Crimée. La plupart, si ce n’est tous, ont poursuivi dans leur vocation révélée, terroriste communiste, opérant des années durant dans un système dont la base même était la terreur. Ce nombre doit être faramineux, mais à leur décharge, ils ont fini par être eux-mêmes victimes du monstrueux système qu’ils avaient mis en branle.

Pour évaluer correctement la tragédie de Crimée, nous devons avoir une idée des chiffres impliqués. Les estimations varient de 12 000 à 120 000, mais de nombreux chercheurs pensent que le véritable nombre doit se situer entre 50 000 et 60 000, c’est aussi l’avis des auteurs Russes contemporains qui ont accès à au moins certaines des archives. [119]

Il faut y ajouter 20.000 morts dans les camps et 100.000 morts dans la famine, le tout en l’espace de seulement dix-huit mois et sur une très petite zone. Ce schéma s’est virtuellement répété partout où les bolcheviks avaient la main, et il s’est poursuivi de 1917 jusqu’au milieu des années 1950, périodiquement entrecoupé de brèves accalmies. Le régime communiste en Russie a été une interminable et colossale tragédie, perpétrée par une clique de criminels dérangés, surtout Juifs, animés par une idéologie qui n’était rien moins que satanique dans ses manifestations.

Quand on songe que de tels enragés rôdent en silence au cœur de nos sociétés modernes, menaçant en permanence de se coaliser de nouveau pour former une nouvelle tornade noire, cela donne la chair de poule.

Les Palestiniens de Gaza et de Cisjordanie en savent quelque chose.

[FG – Peut-être n’est-il pas inutile de rappeler que :

1 – La peine de mort en Russie avait été abolie le 26 octobre 1917 par décision du IIè Congrès Panrusse des Soviets des Députés Ouvriers et Soldats.

2 – La peine de mort n’existe pas en Israël – à part Eichmann et les assassinats ciblés]

Francis Goumain Adaptation française

Source

Jewish Bolsheviks and Mass Murder: Rozalia Zemliachka and the Jews Responsible for the Bloodbath in Crimea, 1920 – The Occidental Observer

La Terreur rouge de 1918-1922 | C’est… Qu’est-ce que la Terreur rouge de 1918-1922 ?

La peine de mort en Russie a été abolie le 26 octobre 1917. par décision du IIe Congrès panrusse des Soviets des députés ouvriers et soldats.

Notes

[1] For instance, many assert that “the Jews” were responsible for the Holodomor, or the Katyn massacre of Polish officers. I do not doubt that Jews were involved in these episodes—respectively, Lazar Kaganovich and Leonid Raikhman, of course—but documentation is scarce, beyond the major figures. One example of a well-documented Jewish massacre is the murder of the Tsar and his family—the perpetrators being Sverdlov, Goloshchekin, Yurovsky, etc.

[2] The family was certainly Jewish; the sources are unanimous

[3] A perusal of Erich Haberer’s Jews and Revolution in Nineteenth Century Russia (Cambridge University Press, 2004) will amply demonstrate the fact

[4] Barbara Evans Clements, Bolshevik Women (Cambridge University Press, 1997), 37.

[5] Namely, Hesia Helfman. See Haberer, Jews and Revolution, 198-99.

[6] Clements, Bolshevik Women, 23-24. It is Clements’ speculation that the family may have had some tie to the assassins.

[7] Kazimiera Janina Cottam, Women in War and Resistance: Selected Biographies of Soviet Women Soldiers (Nepean, Canada: New Military Publishing, 1998), 426.

[8] Clements, 24

[9] Arthur Rosenberg, the German Marxist historian, says “Marx did not proceed from the misery of the workers to the necessity of revolution, but from the necessity of revolution to the misery of the workers.” The History of Bolshevism (Oxford University Press, 1934), 24. Among the radicals of the American New Left, this was an open secret, taking form in the slogan, “the issue is not the issue.”

[10] Clements, 24.

[11] Rozalia’s new idol Karl Marx also delved into demonic imagery and themes. When he was just eighteen his troubled father asked him in a letter, “That heart of yours son, what’s troubling it? Is it governed by a demon?” See Paul Kengor, The Devil and Karl Marx (Tan Books, 2020), chapters 2-4

[12] Clements, 76

[13] Arno Lustiger, Stalin and the Jews: The Red Book (Enigma Books, 2003), 17. At least one other delegate had some Jewish blood: his maternal grandfather was named Israel Moses Blank. I speak of Lenin, of course.

[14] The top leaders of the Mensheviks were Jews: Julius Martov (real name Tsederbaum), Fedor Dan (real name Gurvich), and Pavel Axelrod. Wikipedia lists eight founders/most important members of the Menshevik faction, and five were Jews. The others were Trotsky and Alexander Martinov (real name Pikker).

[15] Clements, 77-78.

[16] Barricades: Clements, 79. Armored street cars: Richard Stites, The Women’s Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860-1930 (Princeton University Press, 1991), 275.

[17] Pyotr Romanov, Демон по имени Розалия Самойловна (“A Demon Named Rozalia Samoilovna”). Accessed May 20, 2025. https://ria.ru/20180817/1524692966.html

[18] Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Isaac Landman, editor. 1943. “Zemlyachka, Rozalia.”

[19] Clements, 79.

[20] Ibid, 142

[21] See Slezkine, House of Government, 138-39.

[22] Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution (Vintage Books, 1991), 564. This incident took place in the summer of 1918. Zinoviev was boss of Petrograd by virtue of his post as Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet, which was a revolutionary council that the Bolsheviks appropriated for their own use.

[23] This happened a bit later, March 1919, but is indicative of the growing feeling. The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Edited by Stephane Courtois, Nicholas Werth, et. al. (Harvard University Press, 1999), 86.

[24] Pipes, The Russian Revolution, 611-12. In The Black Book of Communism, page 87, we read, “In Orel, Bryansk, Gomel, and Astrakhan mutinying soldiers joined forces with [striking workers], shouting “Death to Jews! Down with the Bolshevik commissars!”

[25] The assassinations were of powerful Petrograd-based Jewish Bolsheviks: Vladimir Volodarsky (real name Moisey Goldshtein) was commissar of the press, censorship and propaganda, a “terrorist” and hated figure according to his fellow Bolshevik Lunacharsky; he was shot down June 20. The head of the Cheka in the city, Moisey Uritsky, was shot and killed the same day as the attempt on Lenin, August 30.

[26] The “military commissar was one of the key military innovations of the Reds during the civil wars. These commissars acted as the representatives of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the Soviet government and were attached to military formations . . . at all levels, so as to ensure political control over them . . . When, over the course of 1918, the Red Army became a mass conscript army, dominated by peasants, the military commissars (or voenkomy) assumed also a larger ideological and agitational role . . .” Jonathan D. Smele, Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 1916 – 1926 (Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 746. These were the political commissars that Hitler later targeted in his 1941 Commissar Order.

[27] “A Red brigade commander named Kotomin who defected in 1919 reported “that [the ranks of the commissars] included . . . ‘of course, almost a majority of Jews.’” Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War (Pegasus Books, 2008), 62.

[28] Stites, Women’s Liberation Movement, 321

[29] Clements, 182.

[30] Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory: A History of the Russian Civil War (Simon and Schuster, 1989), 386

[31] George Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police (Clarendon Press, 1986), 114.

[32] Alexis Wrangel describes the family and the Baron charmingly in General Wrangel: Russia’s White Crusader (New York: Hippocene Books, 1987).

[33] Lincoln, Red Victory, 443-48.

[34] Ibid, 448.

[35] For Revolutionary Committees, see Smele, Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 938 and 1378.

[36] The Frenchmen Jerome and Jean Tharaud wrote a book about it, giving it the apt title When Israel is King. It is back in print, available at Antelope Hill Books. A long review appeared on the Occidental Observer in April 2024. The man writing under the name “Karl Radl,” whose research on Jews is prolific, gives a detailed examination of the Jewish personnel involved here: https://karlradl14.substack.com/p/the-jewish-role-in-the-hungarian

[37] Most of the information in this paragraph comes from Smele, Historical Dictionary of the Russian Civil Wars, 640-41.

[38] Angelica Balabanoff, My Life as a Rebel (New York, 1968), 224.

[39] Victor Serge, Memoirs of a Revolutionary (New York Review of Books, 2012), 220.

[40] Serge, 163.

[41] “Samuil Davydovich Vulfson,” in Russian-language Wikipedia. Accessed May 17, 2025. https://fi.wiki7.org/wiki/Вульфсон,_Самуил_Давыдович. I do not have a source that identifies this man as a Jew, but I am confident he is, mainly because of the name. “AI Overview” states: “Vulfson is a surname of Jewish origin, specifically Ashkenazi . . .”

[42] Branko Lazitch and Milorad Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, revised edition (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press. 1986), 160.

[43] Slezkine, The House of Government, 289.

[44] Georgy Borsanyi, The Life of a Communist Revolutionary, Bela Kun, (Columbia University Press, 1993), 236. Borsanyi was a Jewish Communist.

[45] Serge, 248.

[46] Clements, 184. Georgy Borsanyi also depicts him as taking an active role, 241.

[47] Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semyon_Dukelsky) and A. N. Zhukov, Memorial Society, “Semyon Dukelsky.” https://nkvd.memo.ru/index.php/Дукельский,_Семен_Семенович

[48] From Russian-language Wikipedia, Дукельский, Семён Семёнович, “Semyon Dukelsky” https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Дукельский,_Семён_Семёнович

And a Belarusian website on Human Rights: https://protivpytok.org/sssr/antigeroi-karatelnyx-organov-sssr/dukelskij-s-s

[49] Alexei Teplyakov, Иван Данишевский: чекист, авиастроитель, публицист (“Ivan Danishevsky: Chekist, Aircraft Builder, Publicist”) Accessed May 26, 2025. https://rusk.ru/st.php?idar=57915

[50] Rayfield, Stalin and His Hangmen, 311 and 396.

[51] Jews in the Red Army: “Lev Mekhlis.” Yad Vashem. Accessed June 6, 2025. https://www.yadvashem.org/research/research-projects/soldiers/lev-mekhlis.html

[52] Donald Rayfield, Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him (Random House, 2004) 83, 358. Rayfield is not a historian, but a professor in Russian and Georgian literature. This book is quite interesting, being larded with information about the men—often Jews—who killed millions for the Communist regime.

[53] Borsanyi, Bela Kun, 31 and 212.

[54] Borsanyi, 275.

[55] Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: A History of the Russian Revolution (Viking, 1997), 720.

[56] Sergey Melgunov, The Red Terror in Russia (London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1926), 76-77.

[57] Ibid, 76

[58] Vladimir Brovkin, Behind the Front Lines of the Civil War (Princeton University Press, 1994), 345-46.

[59] Russian-language Wikipedia, “Red Terror in Russia,” (https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Красный_террор_в_Крыму) citing Авторский коллектив. Гражданская война в России: энциклопедия катастрофы (“Civil War in Russia: Encyclopedia of Catastrophe,” 2010) Editor D. M. Volodikhin. Volodikhin claims his estimates are based on official Soviet sources.