Henry Pelham (1694–1754), Whig Prime Minister who introduced the Jew Bill in Parliament in 1753

Part I: The English Common Law Basis of Tory Anti-Judaism

A legal case involving Robert Calvin, although seemingly unrelated, would play a key role in shaping attitudes and beliefs about Jews and Jewishness until the mid-nineteenth century. The plaintiff was born in Edinburgh, two years after the Union of the Crowns in 1603. Some land was purchased on his behalf, to test whether his Scottish parentage was an impediment to ownership of English real property. However, it was promptly confiscated because, it was claimed, his birth had occurred outside the “ligeance” or dominion of the English Crown. This meant that Calvin, from an international perspective, was an alien. In 1608, the Lord Chancellor and justices of the Exchequer Chamber ruled in favor of the plaintiff, reasoning that since Scotland and England were ruled by the same monarchy, Calvin’s birth had actually occurred within the ligeance of King James I, making him a full subject with the same rights as an Englishman. The court concluded that he had been wrongfully dispossessed of the land.

The Elizabethan jurist Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634) used Calvin’s case to define the proper legal relationship between infidels and Christians:

All infidels are in law perpetui inimici, perpetual enemies (for the law presumes not that they will be converted, that being remota potentia, a remote possibility) for between them, as with the devils, whose subjects they be, and the Christian, there is perpetual hostility, and can be no peace.[1]

Since Jews were infidels, they were “perpetual enemies” subject to a plethora of civil and legal disabilities. In the First Part of the Institutes of the Lawes of England (1628), Coke wrote: “If the witness be an infidel, or infamous, or of non-sane memory, or not of discretion, or a party interested, or the like, he can be no good witness.”[2] This meant that Jews, because they were infidels, were not allowed to bear witness or testify in a court of law, even in cases of assault, robbery and murder. As far as English jurisprudence was concerned, the Jew was a legal non-entity.

Because Jews were perpetual enemies, certain interactions between Christians and Jews were punishable by death. In the Institutes, Coke “found that by the ancient laws of England, that if any Christian man did marry with a woman that was a Jew, or a Christian woman that married with a Jew, it was a felony, and the party so offending should be burnt alive.”[3]

This was based on legislation recorded in the medieval Fleta, seu Commentarius juris anglicani (circa 1290):

Those who have connection with Jews and Jewesses or are guilty of bestiality or sodomy shall be buried alive in the ground, provided they be taken in the act and convicted by lawful and open testimony.[4]

In Coke’s opinion, Jewish-Christian relations were best governed by medieval common law, such as King Edward’s Statutum de Judaismo (1275) or the anonymous Fleta. His reverence for medieval law was based on an a posteriori approach to English jurisprudence. In his Reports, he wrote:

For any fundamental point of the ancient common law and customs of the realm, it is a maxim in policy, and a trial by experience, that the alteration of any of them is most dangerous for that which had been refined and perfected by all the wisest men in former succession of ages and proved and approved by continual experience to be good & profitable for the common wealth, cannot with great hazard and danger be altered or changed.[5]

The doctrine of the “Jew as perpetual enemy” remained on the books until the re-admission of the Jews in 1656. By that time, English jurists had begun to simply ignore it. It would be revived again by Tory parliamentarians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

In addition to the “perpetual enemies” doctrine, there was the “Christianity is law of the land” doctrine, also based on Coke’s legal analysis of Calvin’s case. The law of nature “which God at the time of creation of … man infused into his heart” was the “Moral Law,” which was, Coke said, “immutable,” existing “before any judicial or municipal law in the world.” This Christian “Moral Law” was a “part of the laws of England.”[6] Sir Matthew Hale, in the case of Rex v Taylor (1676), affirmed Coke’s position as the bedrock of English jurisprudence: “Christianity is parcel of the laws of England; and therefore to reproach the Christian religion is to speak in subversion of the law.”[7]

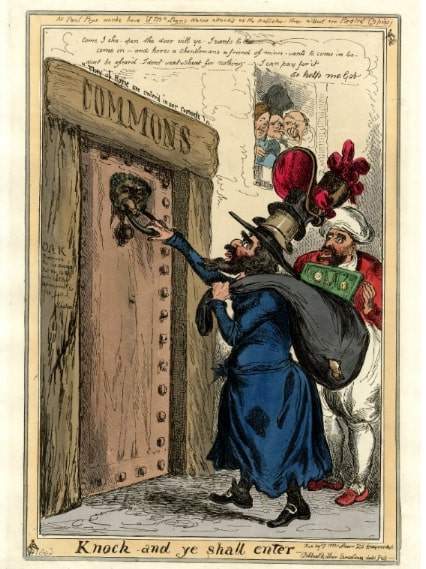

The “Christianity is law of the land” doctrine served as the legal justification for relegating Jews to second-class citizenship until 1858, when the Jew Lionel de Rothschild was allowed to take his seat in the House of Commons.

Part II: The Jews, the Whigs and the Tories, 1753

Jews were barred from full participation in English life because they rejected Christianity. They could only be “endenized by royal letters-patent” to become permanent residents; they could not become full subjects because parliamentary naturalization required taking the Eucharist. Compared to parliamentary naturalization, endenization had certain drawbacks. It was not retroactive, so if a Jew had been endenized after the birth of his children, they would not be able to inherit his property. The only advantage of endenization was that Jews were granted the right to participate in the lucrative colonial trade.

Endenized Jews, like other non-Anglican residents, “could not hold municipal office, be called to the bar, obtain a naval commission, take a degree in the two universities, vote, or be elected to parliament” (Rabin, 2006). Unlike other non-Anglican residents, endenized Jews were subject to additional restrictions. They could not participate in commerce on the same terms as other British subjects; they were not allowed to own real estate without parliamentary approval, nor were they allowed to become members of the most prominent West Indian trading companies. They were also compelled to pay alien customs duties on imported goods. These commercial disabilities hit the more commercially enterprising Jews very hard, disproportionately affecting the Sephardi community, rather than the Ashkenazi. The disproportionate impact stemmed from socioeconomic differences between Jewish ethnicities:

The Ashkenazim were poorer and tended to integrate less well; they accounted for most of the Jewish pedlars and small-dealers, and were associated in the English cultural imagination with the figure of the wandering Jew. … The Sephardim, by contrast, traded on a larger scale; wealthier and more politicised, they were arguably laxer about religious observances, shaved, and dressed in English fashions. (Latimer, 2015b)

Whether lending money to the Crown, to provision British troops and fight wars overseas, or hawking secondhand clothes in London’s slums, the Jews were disproportionately engaged in commercial and financial activity, just as they had been on the Continent. In London, the Sephardi Jewish community became so wealthy and influential they were able to successfully lobby the Whig government for naturalization. In 1753, Joseph Salvador, a prominent Sephardi Jew, convinced Henry Pelham’s Whigs to introduce the Jewish Naturalization Bill, or “Jew Bill” for short, in the House of Commons. The purpose of the bill was not to naturalize Anglo-Jewry, but to eliminate holy communion as a requirement for parliamentary naturalization, allowing Jews to participate in English commercial life as if they were full subjects of the British Empire.

The Jew Bill, drafted by Pelham and his brother, the Duke of Newcastle, was steered through Parliament as “a favor to some of the Sephardi mercantile elite who had been active in supporting the financial policies of the ministry and who had now solicited a favor from the government.”[8] Among the most prominent Jewish financial contributors was Samson Gideon, a Sephardi Jew who had loaned the Hanoverian Crown ₤1,700,000 (more than $2 billion in today’s dollars) to suppress the Jacobite Uprising of 1745 and establish order in the aftermath of the rebellion.

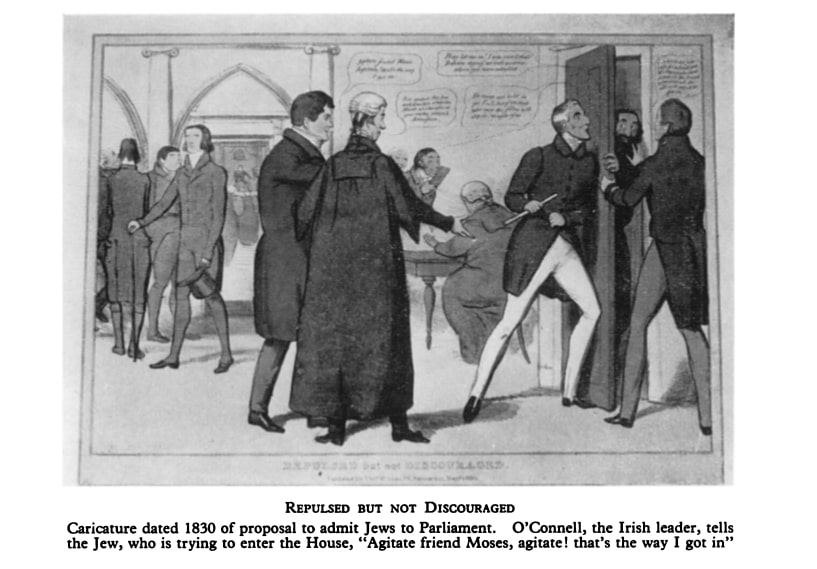

The English public believed that officials of Pelham’s ministry had received Jewish bribes in exchange for moving the Jew Bill through the Commons, a result of the government’s extensive financial dealings with Sephardi financiers and merchants. This belief was further disseminated by the anti-Jew Bill prints of 1753, where Jewish bribery of government was a common theme. In one such engraving, “The Grand Conference or the Jew Predominant,” Samson Gideon is shown bribing the Duke of Newcastle and Henry Pelham with a bag of gold in exchange for passage of the Jew Bill.

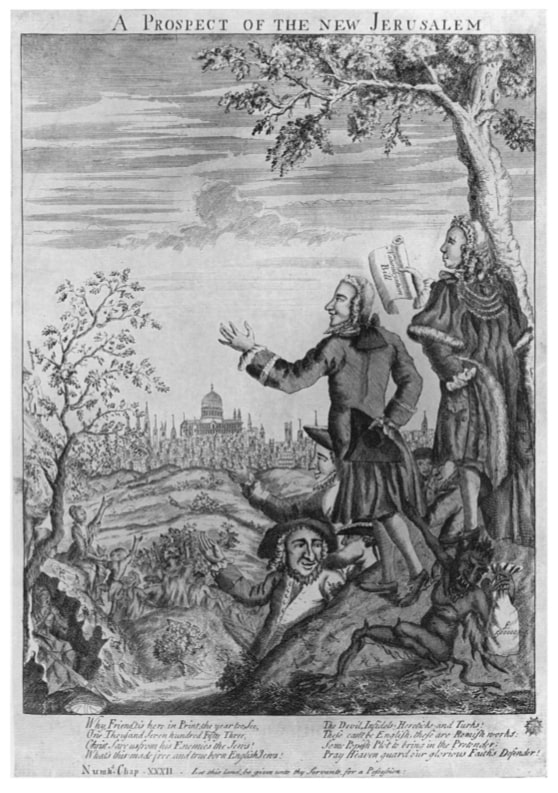

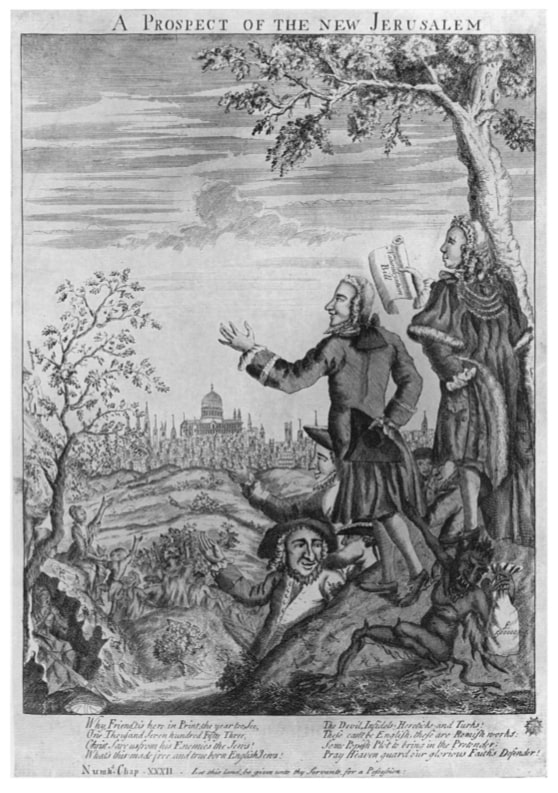

In another, “A prospect of the New Jerusalem,” the London Mayor, standing on a hill with municipal officials, holds a paper that says “Naturalization Bill”; in the immediate foreground is the devil with a bag marked ₤500,000. He points toward a group of Jews in the background, implying that the Jew Bill had been introduced in the Commons because of Jewish bribery. The widespread perception of Jewish financial meddling at the highest levels of government was, of course, grounded in solid fact.

Although the Jew Bill was a reward for Jewish financial assistance to the government, it inadvertently served the purpose of attracting more wealthy Jewish immigration to England. This allowed the Jewish financial elite to strengthen and consolidate its power and influence over the English Crown and economy, while threatening the ethnic cohesiveness and political stability of the English nation. Since the re-admission of the Jews, anti-Jewish laws—based on Lord Coke’s legal analysis of Calvin’s case—had been slowly relaxed to encourage more Jewish settlement. It was felt among Anglo-Saxon elites of the time that having Jewish merchants on English soil would help stimulate commerce and enrich the treasury.

In parliament, polarization reflected ideological differences between Whigs and Tories on the economic benefits of immigration. Thomas W. Perry writes:

In the 1750’s these orthodox opinions — exclusionist with regard to the whole economy, and restrictionist with regard to movement within it — were under attack, and so were all the more tenaciously held and alertly defended. The criticism came principally from a school of protoliberal pamphleteers who insisted that the economy would benefit both from an infusion of new blood, as it were, and from a freer internal circulation. The debate also had a political aspect, since most of these writers seem to have been Whig partisans, and since Henry Pelham was on record as favoring, at least in principle, not only a general naturalization but also ‘the repeal [of] every law, tending to establish a monopoly, in any quarter of the realm.’[9]

Since the Tories prioritized nation over economy, they were staunch economic protectionists. As the proto-conservatives of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, they believed that restrictions on naturalization served the national interest because it protected natives from the demoralizing effects of foreign competition. In parliamentary debates, they focused on the potentially damaging effects of the Jew Bill on the English domestic and international economy. The Jews were considered especially dangerous because of their reputation for ruthlessness and lack of moral scruples in their financial dealings with non-Jews.

John Perceval, the second earl of Egmont, remained true to his Tory beliefs when, in a speech before the Commons, he dismissed Jewish naturalization as an economically harmful policy:

The trade of the Jews, as it appears by the oldest of our histories, and the earliest records both here and in other countries, was usury, brokerage, and jobbing, in a higher or a lower degree. By this traffic, in former ages, they distressed and ruined the Christian subjects in such numbers everywhere, as to draw down upon them from time to time the resentment of all nations, and in this traffic they have improved so far in this age, as now to ruin whole kingdoms instead of individuals, by aiding ministers to beggar the states they serve, by which traffic also they have greatly aided to plunge this nation into a debt of near eighty millions.

Lord Egmont said the Jews were a class of shady businessmen who had refused to engage in any “real commerce” or “honest trade of merchandize” since re-admission to England. This was understandable because, from the medieval period on, Jews were acknowledged by Europeans as a universal symbol of international financial corruption, a stereotype with more than a grain of truth to it. Contrary to the Whiggish belief that Jewish resettlement would economically benefit the of the kingdom, the potential Jewish contribution to English commercial life, in light of the historical record, was nugatory:

Since therefore the naturalization of the Jews tends to no important addition of property to this kingdom; to no possible increase in strength; to no improvement in manufactures; to no extension of the commerce of the kingdom; this bill can be no measure of utility, and cannot merit the sanction of this House.[10]

Sir John Barnard, a dissenting Whig, focused on the negative impact Jewish resettlement would have on native English productivity. He argued that Jews were a net fiscal drain on English society. Barnard demanded a permanent moratorium on all Jewish immigration because it would

in time render it impossible for any Christian to carry on any trade, either foreign or domestic, to advantage; Jews may become our only merchants, and our only shop-keepers. They will probably leave the laborious part of all manufactures and mechanical trades to the poor Christian, but they will be the paramount masters.[11]

Jewish economic control of the English economy was not the worst that could happen. According to Sir John Barnard, the Jews were a race of destroyers. Allowing Jews to compete on the same terms as Englishmen was tantamount to ethnic suicide:

It is madness, if not worse, to put … foreigners upon an equal footing with natives, because it only enables the former to take the bread, or part of the bread, out of the mouths of the latter, without increasing in the least the national trade or commerce.[12]

Notwithstanding the determined opposition of Tories and dissenting Whigs, the bill passed through both houses of Parliament, and was given royal assent by King George II. There was little dispute among MPs, since both houses were Whig-dominated. The Whigs, ideologically proto-liberal, were usually sympathetic to Jewish causes.

James Shapiro writes:

Insofar as Englishness was being reconstituted socially, politically, economically, and religiously at this time, the attempt to naturalize Jews—and thereby do away with that which distinguished Englishness from Jewishness—proved explosive.[13]

Passage of the Jew Bill was followed by a massive outcry among Tories; a wave of anti-Semitism, never before seen since the days of Edward I (r. 1272–1307), swept across England. The ferocity of this public reaction to Jewish naturalization was due, in part, to widespread perception of Jewish foreignness:

The non-Jewish world … viewed the Jews in their midst as a separate people, regarding even native-born, highly acculturated Jews as different in kind, marked off by a distinctive, irreducible essence or otherness that remained despite their adaptation to English conditions. In fact, the belief in Jewish distinctiveness was so embedded in popular consciousness that converted Jews, including the children of Jews baptized at birth, were commonly referred to as Jews.[14]

Through their attitudes and behavior, Jews reinforced English perceptions of their foreignness and clannishness that was based on kinship and thus independent of religious observance:

The mass of Jews … socialize[d] and marr[ied] within their own community, irrespective of their attachment to Jewish ritual and worship. Moreover, they continued to think of themselves as Jews first and foremost, as members of a distinct people, and not as Englishmen, even if they were native-born citizens who had known no other homeland. In this respect, they were no different from their ancestors, who had lived in conditions of much greater isolation from the surrounding society.[15]

The emergence of English ethno-racial consciousness was a consequence of Jewish ethno-racial and cultural foreignness. Jews would maintain a fully articulated Jewish identity even when fighting for Jewish naturalization and, in the nineteenth century, “emancipation.”

Publish’d for Mr Foreskin at the great pair of Breeches in the Parish of Westmter Satire on the Jewish Naturalization Act suggesting that the Duke of Cumberland is to be circumcised or castrated (1753)

Widespread perception of Jewish foreignness and self-identification served as fertile ground for the growth of extra-parliamentary opposition to Jewish naturalization. According to scholar Todd M. Endelman, the “agitation sparked by passage of the Jew Bill in 1753 functioned as a lightning rod for the articulation of nationalist sentiments at the time.”[16] Through pamphlets and newspaper editorials, ballads and songs, etchings and engravings, Tories were able to awaken a sense of English national pride in the common people, reminding them of the dangers of ethnic dilution and loss of Christian religious belief if Jews became Englishmen. Although Whigs would fret that Jews would remain an ethnically indigestible element on English soil, the Tories worried about the fragility of English ethnic identity and how easily it could be destroyed through assimilation of Jewry. As a verse of contemporary doggerel had concluded about passage of the Jew Bill:

Such actions as these most apparently shews,

That if the Jews are made English, the English are Jews.

Outside Parliament, Tory opponents relied on a combination of religious, patriotic, legal and economic arguments to convince the English public of the dangers of Jewish naturalization. Jonas Hanway, philanthropist and anti-Jewish pamphleteer, objected to Jewish naturalization because it was “as unnatural a mixture in the body politic, as bread and arsenic in the human body; and therefore such a mixture could produce no happiness, but, on the contrary, dishonor and reproach.”[17] The Jews were a dangerous foreign element—a poison—that destroyed everything it touched. Hanway further argued that because the Jews were a separate nation, guilty of “unparalleled iniquity,” such as “the national crime of crucifying the Lord of life,” their naturalization was undesirable.

In the anonymous pamphlet A Modest Apology for the Citizens and Merchants of London, who petitioned the House of Commons against Naturalizing the Jews, it was argued that Jews could never be naturalized because they were “Rebels against God” who were guilty of deicide.

“You know a Jew at first sight,” the author wrote:

Look at his eyes. Don’t you see a malignant blackness underneath them, which gives them such a cast, as bespeaks guilt and murder? You can never mistake a Jew by this mark, it throws such a dead, livid aspect over all his features, that he carries evidence enough in his face to convict him of being a crucifier.[18]

If the Jews were ever to become English citizens, the native English would share in the guilt of Christ’s murder, becoming “crucifiers” or “Christ-killers” themselves. Jewish naturalization would also subject the English people to divine wrath and punishment.

The High Church evangelical William Romaine wrote:

The Jews then in the Eye of the Common Law were always looked upon as Aliens – neither natural-born Subjects, nor capable of being naturalized – but perpetual Aliens, because there is no reasonable Ground to expect they will ever be converted, their Opposition to the Christian being as implacable as the Opposition of the Devil: For they are his Subjects, not Christ’s, and as Subjects to the Devil, they are in perpetual Hostility with Christ, so that there can be no peace between them and Christians.”[19]

Jewish naturalization was impossible because of Lord Coke’s “perpetual enemies” doctrine. If Jews are the “avowed enemies of Christianity,” making them citizens would violate English law, since it was based on Christian principles. Romaine continued:

The Jews Murdered Christ, and would murder us if they had Power: They blaspheme Christ and his Religion; so that they are Murderers and Blasphemers Convict; and who ever heard of a natural-born Murderer, or a natural-born Blasphemer? For murdering and blaspheming Christ, God drove them out of the Holy Land, and made them Vagrants all over the Earth, and who ever heard of a natural-born Vagrant? Or a natural-born English-Foreign-Jew? i.e., a free Slave-born in the Liberty of Bondage. And yet however absurd this may seem, we have these Native Foreigners imported among us. We have Murderers, Crucifiers, Blasphemers, Vagrants all become natural-born Jew-Englishmen—in opposition to our History and Records—to our Constitution and Laws—to the Laws of God and to Reason and common Sense—which declare with one Voice, That no infidel Jew can be a free-born subject of our Christian society.[20]

The Jew Bill was to be rejected because the Jews were both Christ-killers and blasphemers. A “natural-born Jew-Englishman” was a contradiction in terms.

The Jews were not only “subjects of the Devil,” but were emblematic of the worst excesses of international finance. “Money is their idol. Money they most ardently worship.” If the essence of Judaism is money, then Jewish relations with non-Jews will always be economically predatory, just as they were during the days of King Edward I.

In Romaine’s discussion of Anglo-Jewish history, the Jewish “Money-Engine” figures prominently. The Jews successfully bribed William the Conqueror and Oliver Cromwell with their “ill-gotten Wealth”; seduced by the Jew’s “all-powerful Gold,” these English statesmen gave them carte blanche to grow rich through plunder of the nation’s inhabitants.

Beside the pamphleteers, there were the Tory newspapers that warned the English public of the dangers of Jewish naturalization. Foremost among these was the London Evening Post. In an editorial of May 17, 1753, a gentleman calling himself “Old England,” fearing the English would be “sold into Captivity under the Jews,” wrote:

This supposed Bill is nothing less than giving ourselves, our Liberty, Property, and Religion, into the Hands of the Jews. For it is an open, full invitation of the whole scatter’d Race to come and take Possession of all our Estates. For who knows not, that they have more Millions to spare than would purchase all our Island. … [I]f this Bill should pass, it is more than probable, that in Ten Years our Tenants may have Jewish Landlords, Two thirds of our Free holders be oblig’d to be circumcised, or vote as they are order’d. … God preserve us from Jewish Power!

In an article on the consequences of the Jew Bill, published June 23, 1753, an author asked rhetorically:

Doth not this give rise to a new interest in Great Britain, which never was known or heard of before? A Jewish landed interest? … will not dominion follow property? Or are our present managers in possession of a secret of frustrating the operation of this hitherto uncontested principle? Can they allow the Jews to purchase the half, or three parts, of the lands of the kingdom, and still withhold from them that weight and influence which is the consequence of property?

What would the distant future look like after passage of the Jew Bill, given that “dominion follows property”? The London Evening Post attempted to answer this question with the dystopian “News from One Hundred Years hence,” a satirical jibe at Pelham’s ministry. The year is 1853, England has been taken over by wealthy Jews, renamed Judea Nova and placed under the rule of the Sanhedrin. The Merchant of Venice is banned, “Galileans” are hunted down and shot on site, pork is illegal and naturalization of the few remaining Christians is now under debate.

The propaganda seems to have had real-world consequences. While the Jew Bill was law of the land: “Jewish peddlers were insulted and harassed in the streets and the murder of Jonas Levi in November of 1753 may have resulted from the passions sparked by the bill” (Rabin, 2006). Anti-Semitic polemicists portrayed Jews as money grubbing and cunning; they were traitorous foreign interlopers who were suspicious of outsiders. Newspapers all around the country ran story after story about what “ravenous, destroying Wolves,” “blasphemers and crucifiers” and “Children of the Devil” the Jews were. Because of the Jew Bill, patriotic Englishmen feared that:

Britain would be swamped with unscrupulous brokers, jobbers, and moneylenders, who would use their ill-gotten gains to acquire the estates of ruined landowners. Moreover, because dominion followed property, Jews would control Parliament (which would be re-named the Sanhedrin), convert St. Paul’s to a synagogue, circumcise their tenants, and perpetrate countless other anti-Christian crimes.[21]

Because of the widespread Tory-led opposition to the Jew Bill, Pelham’s Whigs were forced to repeal it in December of 1753. The status quo returned; Jewish immigration, which had been ongoing since Cromwell’s decision to re-admit the Jews in 1656, continued unabated.

Vox Populi or the Jew Act Repealed (December, 1753)

The Jews pouring into England were now predominantly lower-class Ashkenazim from Central Europe, rather than the wealthy and cosmopolitan Sephardim of Spain and Portugal. This new influx stoked the fires of English anti-Semitism. The observations of German tourists in eighteenth-century Georgian England furnish us with a valuable source of information about contemporary Anglo-Jewry. Panikos Panayi writes:

Hostility … developed during the eighteenth century towards poor Jews. The German traveller Carl Philip Moritz wrote that ‘antipathy and prejudice against the Jews, I have noticed to be far more common here, than it is even with us, who certainly are not partial to them.’ Hostility focused particularly on the allegation that they played a large part in the peddling of stolen goods, which resulted in attacks upon them to the extent that ‘Jew-baiting became a sport.’ One German traveller wrote of ‘the general discontent of the nation occasioned by the German Jews, a class of men detested as the offscourings of humanity.’[22]

Mass immigration of Jews to England led to an increase in the national crime rate, with Jews among the most visible criminal elements of the London underground. Endelman writes:

Not many years after the controversy over the Jew Bill, Jewish criminal activity reached such a pitch that it became a matter of concern to the leaders of Anglo-Jewry. In the 1760s, the number of Jews sentenced to death or transportation at the Old Bailey jumped to thirty-five—almost double what it had been in the previous decade—and then in the 1770s it rose to sixty-five.[23]

The emigration of poverty-stricken, crime-prone Ashkenazim from Central Europe was reduced to a trickle during the French Revolutionary Wars of the 1790s, giving Ashkenazim in London and elsewhere time to assimilate Anglo-Saxon behavioral norms. By the 1820s, the Jews and their Whig allies would be ready to take on the Tories once again, but this time in the name of “Jewish emancipation,” an obvious misnomer. Compared to conditions on the Continent, the disabilities faced by Anglo-Jewry were mild, with Jews still having considerable upward mobility and freedom. In fact, English Jews were the envy of Central European Jewry, which is why so many immigrated to England during the latter half of the eighteenth century.

[1] Seventh Part of Sir Edward Coke’s Reports, pg. 397

[2] A readable edition of Coke upon Littleton by T. Coventry, 6b

[3] Third Part, pg. 89

[4] Vol.1, pg. 90

[5] Fourth Part, pg. v, vi

[6] Seventh Part, pg. 392

[7] http://www.commonlii.org/uk/cases/EngR/1726/773.pdf

[8] Endelman, 1999, pg. 59

[9] 1962, pp. 40-41

[10] The Parliamentary History of England, From the Earliest Period to the Year 1803, 1813, Vol. XIV, pg. 1424

[11] Ibid, pg. 1393

[12] Ibid, pg. 1392

[13] 1999, pg. 196

[14] Endelman, 2002, pg. 68

[15] Ibid, pg. 67

[16] 2002, pg. 6

[17] Letters Admonitory and Argumentative by Jonas Hanway (London, 1753), pg. 22

[18] Perry, 1962, pg. 93

[19] Ibid, pg. 10

[20] An answer [by W. Romaine] to a pamphlet [by Philo-patriæ] entitled, Considerations on the bill to permit persons professing the Jewish religion to be naturalized, 1753, pp. 21-22

[21] Endelman, 2002, pg. 75

[22] 1996, pg. 47

[23] 1999, pg. 196