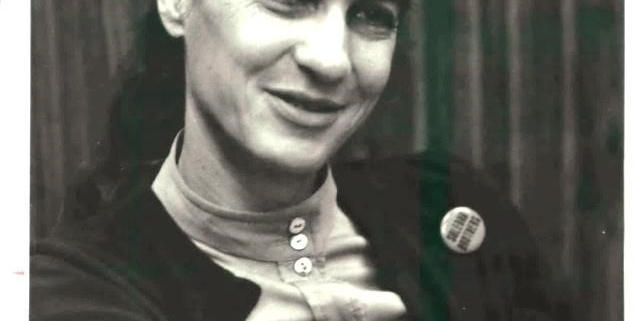

The Life and Times of Fay Stender, Radical Attorney for the Black Panthers, Part 2

Legal Work for the Movement

When she returned to Berkeley, Fay “felt energized.”[i] So did other returnees. Mario Savio, fresh from Mississippi, launched the Free Speech Movement (FSM) at UC Berkeley that fall, kicking off the wider radical crusade of the 1960s. When the police began to clear Sproul Hall of protesting students in the early morning of December 3, Bob Treuhaft was the first one arrested; he had been called by Savio and arrived just in time for the bust.[ii] The Free Speech Movement—surprise—was every bit as Jewish as Freedom Summer. The occupiers of Sproul Hall held a Hanukkah service during the sit-in, and the biggest base of support for the radicals came from the Jews in the student body.[iii] Fay “relished seeing the Berkeley campus develop into a hotbed of Movement fervor.”[iv] The fact that it was a Jewish movement was presumably a source of pride for her, given her strong Jewish identity.

The arrestees called for legal help and Fay jumped into action. Her energy at times like this could be awe-inspiring, and the FSM members “secretly fell in love with her.”[v] Over the years, many people would describe Fay as attractive, intelligent, and generous, especially when she could immerse herself in a cause. She helped arrange for bail and performed other legal work in a blur of activity.

Shortly afterward, Fay held a Seder (a ceremonial Passover dinner) for SNCC personnel at her home. She “incorporated into it references to Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Civil Rights Movement.”[vi] This was fitting because the Jews had invested heavily in the movement; indeed, they had generally succeeded in guiding the direction of the civil rights campaign from the time they initiated the NAACP in 1909.[vii]

Fay had another reason to feel good in the spring of 1965. She and Marvin reunited and leased a house in the Berkeley flats. They made their home a haven for movement friends, who were excited by yet another looming cause: the Vietnam War. (No rest for the wicked.) They plunged into an effort to help young men resisting the draft and others demonstrating against the war.[viii] Fay, Marvin, and their lawyer friends Peter Franck and Aryay Lenske set up the Council for Justice (CFJ) to provide legal services for the entire range of leftist causes. The Executive Committee of the CFJ included Beverly Axelrod, who would soon make Eldridge Cleaver famous.[ix]

The CJF didn’t last long, but not to worry; there is always another cause, another front in the war against White society. Sure enough, one soon appeared, one that carried a menacing—murderous, even—revolutionary swagger, so calculated to set Jewish hearts aflutter. Better yet, this group was Black, and so would be entirely dependent upon Jewish brains and money.

Eldridge Cleaver and the Revolutionary Glorification of Black Criminality

In the wake of Freedom Summer and the racial rancor it generated within the civil rights movement, more pugnacious Blacks rose to ascendancy in SNCC and other civil rights organizations. Stokely Carmichael became chairman of SNCC in May 1966, and quickly repudiated civil disobedience. He embraced “Black Power” and Black separatism, and by the end of the year he expelled Whites from the SNCC. A position paper worked up to explain the move stated, “All White people are racists.”[x] Jewish revolutionaries were outraged; one cited Jewish support of civil rights organizations and their “strategic role in organizing and funding the struggle,” and concluded “it was clear to everyone that [Jews] were the primary target” of Carmichael’s new racial militancy.[xi] Jews can get awfully sensitive when their revolutionary proxies get it into their heads to steer their own way.

It was in this context that the Black Panthers appeared in the Bay Area in October 1966. The Black Panthers reviled the “White power structure” but were open to alliances with White radicals. Jewish leftists immediately connected with their movement. Advocacy for the Panthers would become the dramatic climax of Fay’s career. She would throw herself into the maelstrom of pro-Panther activism with total incomprehension of their true nature, just like many other Jewish revolutionaries.

We begin with Eldridge Cleaver, because his career was so largely a Jewish creation, and provides necessary background for Fay’s new endeavor. In1966 Cleaver was doing time for attempted rape and attempted murder. His infamous predilection for violating White women would soon be broadcast by Jewish publicists. He read politics and history in prison, but his ideas crystallized upon reading George Breitman’s book, Last Year of Malcolm X: The Evolution of a Revolutionary. Breitman, a Jew, depicted Malcolm at the end of his life as less a religious leader than a socialist revolutionary. “The Malcolm X of the Breitman book went far beyond seeing racism as a flaw in the hearts of the American people. It was endemic to the nation’s economic system, a necessary feature of capitalism. The whole structure had to go.”[xii] The book impacted Black inmates “like a lightning strike.” They now spurned mere reform or talk of civil rights; “[t]here was nothing to be gained by trying to fit in. The very structure of the society would have to be razed.” Cleaver was the inmate “who followed this line of thought most closely.”[xiii] A Jew thus lit yet another spark for Black revolution.

From prison, Cleaver managed to contact Beverly Axelrod, a Jewish lawyer and veteran radical. He hoped that he could pay her legal fees with his writing, and she could win his parole. Axelrod smuggled forbidden literature into prison for Cleaver, and he gave her his numerous tracts, which she sent to Norman Mailer, whose 1957 essay “The White Negro” reminded more than one critic of Cleaver’s scribblings. With Mailer’s enthusiastic approval, she was able to get Ramparts magazine, soon to become the most prominent publication of the New Left, to publish selections.[xiv] Robert Scheer, editor at Ramparts (son of a Russian Jewess and a German Gentile), also helped place Cleaver’s work in the magazine; his role would become big enough to earn the description of “perhaps the key person to launch the career of Eldridge Cleaver.”[xv] Eldridge Cleaver was a Jewish creation, and the Jews were on their way to replacing the SNCC as their controlled vehicle of social demolition.[xvi]

In August 1966, Ramparts published Eldridge’s “Letters from Prison,” which included this famous passage: “Rape was an insurrectionary act. It delighted me that I was defying and trampling upon the White man’s law, upon his system of values, and that I was defiling his women.”[xvii] Whatever Beverly Axelrod thought of this passage, it didn’t stop her from falling in love with him. By the time she got him out on parole at the end of 1966, they were lovers and planned to marry. Cleaver’s book Soul on Ice came out in the spring of 1967. The book “whipped tough cultural observations in with a froth of sexual lore, and the result was a violence-steeped Maileresque Black sexual-political myth …”[xviii] It featured letters to and from Beverly and was dedicated to her, “with whom I share the ultimate of love.”[xix] Jewish media sources received it rapturously; the lefty Jewish critic Maxwell Geismar in his introduction to the book wrote that Cleaver was “simply one of the best cultural critics writing today.”[xx]

Cleaver could portray his crimes as politically motivated all he wanted, but without Jewish publicists, it would have amounted to nothing. Because he was able to gain the ear of radical Jews, the myth of the criminal-as-revolutionary was born: “crime . . . became a revolutionary challenge to the state.”[xxi] This idea—putting the final touch on a dangerous concoction—created “room for criminal male violence in the ideology of the New Left.”[xxii] A direct path was laid down to domestic revolutionary violence and terrorism. It led in a straight line from the Black Panthers, to the Weathermen, the Symbionese Liberation Army, and now, Antifa.

Huey Newton and Fay Stender

At a party celebrating the publication of Soul on Ice, Fay Stender met Cleaver and toasted his engagement to Axelrod.[xxiii] (The engagement would not last long; Cleaver soon abandoned her for a much younger woman. Cleaver later admitted that he used Axelrod, eleven years his senior, to get out of prison.) It was through Axelrod that Fay would become involved in the case that made her famous.

However, Fay was depressed again. She was no closer to a full partnership in the firm of Garry & Dreyfus; she mostly did research for the “name” partners. She was envious of Beverly Axelrod, the toast of the radical community, and Marvin had embarked upon yet another affair. She needed a new cause. As it happened, it wasn’t long in coming: in the early morning hours of October 28, 1967, the thuggish founder of the Black Panthers, Huey Newton, murdered John Frey.

Oakland police officer John Frey had pulled over a vehicle with Newton and a friend inside. Ten minutes later Frey was dying of five bullet wounds, two in the back from close range.[xxiv] An hour later Newton showed up at Kaiser Hospital with a gunshot wound in his abdomen. There the cops caught up to him; so did Charles Garry and Fay Stender. Eldridge Cleaver, who had joined the Panthers after his release from prison and now stepped up as leader, had called Axelrod for help and she called Garry.[xxv] Fay “would never forget the impact of seeing Huey Newton lying half-naked under armed guard. . . . At first sight, she felt a strong sexual attraction.”[xxvi] Her depression vanished; she “instantly realized this might be the career break she was looking for.” She would be at the center of the “hottest Movement case around”: a capital murder trial for a Black man “struggling” against the “racist” American system.[xxvii]

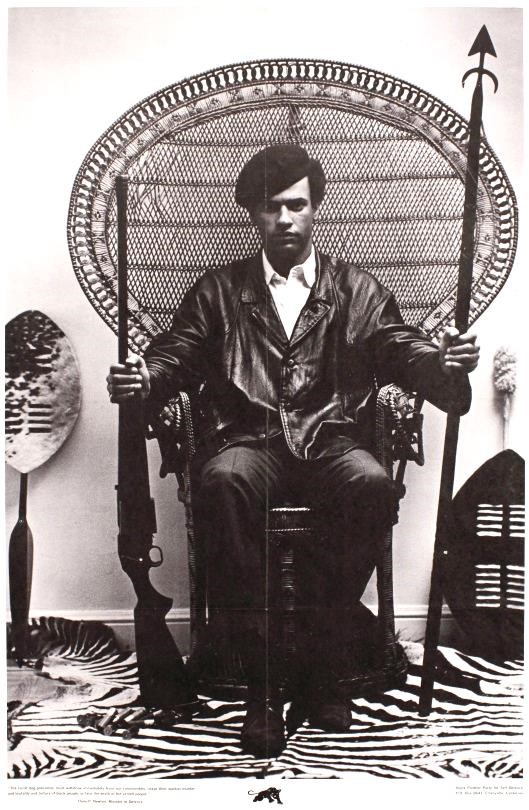

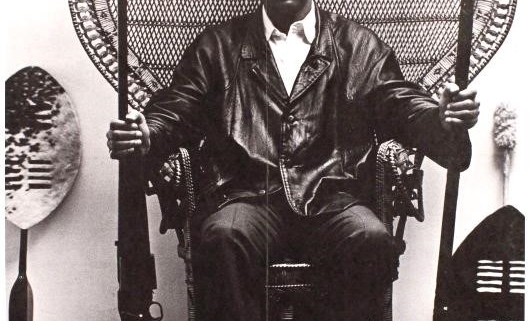

Huey Newton in Beverly Axelrod’s apartment, 1967. Props by Cleaver.

Fay wasn’t the only turned-on radical. Newton (who reportedly had a Jewish grandfather[xxviii]) and the Panthers had already gotten major press coverage; less than three months before Frey’s murder, Israeli-born Sol Stern had done a write-up on the Panthers for New York Times Magazine (August 6). This was the first exposure the Panthers had received in the mainstream press. “Stern had asked Newton if he was truly prepared to kill a police officer; Newton replied that he was.” Stern couldn’t help concluding that, for the Panthers, “the execution of a police officer would be as natural . . . as the execution of a German soldier by a member of the French Resistance.”[xxix] In the immediate aftermath of the killing of Frey, the underground newspaper Berkeley Barb (owned and run by the Jew Max Scherr[xxx]), which had been covering the Panthers steadily since early 1967, “hastily concluded” that the Newton case was a “clear case of police provocation” and declared him a political prisoner.[xxxi] The Barb would continue to cover Newton’s case full-blast.

Many radicals believed that Newton had killed Frey, and hoped it presaged a real revolution.

Fay would assist Garry in the case, along with Barney Dreyfus and another partner, Alex Hoffmann, a diminutive Viennese Jew. Garry planned a “super-aggressive defense . . . raising every possible factual and legal issue,” with a maximum of publicity to arouse sympathy for Newton.[xxxii] Fay, who had virtually no experience in criminal trials, would do research and write motions and briefs that challenged everything that might lead to plausible grounds for a subsequent appeal. Garry would conduct the trial in the courtroom. Nevertheless, the case looked very bad for the defense; everything pointed to Newton having an electrifying end to his career.

Garry planned to put the “racist” American system on trial and the prosecutor on the defensive. Lise Pearlman describes it as the first “Movement trial”; the Chicago Seven Trial was yet to come.[xxxiii] The Panthers and their White backers would mount large demonstrations around the courthouse at each pre-trial hearing and all through the trial, and the leftwing press and its Jewish scribes would provide fawning coverage.

The Panthers at the time of Frey’s death numbered only about a dozen people. With a cause célèbre like Newton imprisoned in a racially explosive murder case, Blacks flocked to the Party. Within eighteen months, there were over forty chapters around the country with 5,000 members. Their paper, The Black Panther, launched in Beverly Axelrod’s apartment, grew to a circulation of over 100,000.[xxxiv] Newton, many remarked, was more valuable in prison, a likely martyr, than free.

The prosecutor quickly obtained an indictment from a grand jury. Fay and Barney Dreyfus immediately prepared a constitutional challenge to the composition of the jury, because it was too White. It didn’t reflect a “cross-section of the community.”[xxxv] They invested immense effort and time on this angle. (Their argument would fail; they would appeal; again denied.[xxxvi]) This, together with their later agitation against the composition of the trial jury, would have the terrible effect of making juries and the judicial process subject to identity politics, and lead to rampant Black juror sabotage of criminal cases against Blacks.

In January 1968, Fay began visiting Newton regularly in the Alameda County Jail. She was “delighted at his warm reception,”[xxxvii] and began dressing more attractively, with makeup, on her visits. She was “but one of a growing number of his new female devotees.”[xxxviii] Newton was able to bamboozle her completely. He told her he learned to read after high school by repeatedly attempting Plato’s Republic. She in turn shared personal details with him, and was soon panting, “he is truly a great man. Huey is a loving, gentle, kind person . . . He has a righteous force, a fierce combination of moral outrage and anger.”[xxxix] What is this but pure female emotion, utterly duped by radical ideology and a dangerous but charming poseur?

In late February 1968, the government released the Kerner Report. It infamously blamed White racism for Black failure and the Black inner-city riots of the preceding few years, providing top-level government backing for the claim that Huey Newton’s actions were simply the result of frustration with oppression.

Five weeks later, after a night of whoring in Memphis, the Reverend Martin Luther King met God, unexpectedly.[xl] In protest, Blacks across the nation attacked and burned down their own communities.[xli] President Johnson had to call in 13,000 troops to quell the violence and arson in Washington, D.C. Amidst the excitement, Eldridge Cleaver gathered four carloads of heavily armed Panthers and set out to “off” some “pigs” and “stoke the image of [the Panthers] as the future revolutionary vanguard.”[xlii] A shootout ensued. Police killed one Panther and hauled Cleaver off to prison. Cleaver insisted he and the Panthers were innocently “preparing a picnic” for the morrow.[xliii] “To the Bastille!” brayed the Berkeley Barb at this “police outrage.” Susan Sontag and Norman Mailer, among others, demanded Cleaver’s release.[xliv]

Meanwhile, Fay worked round the clock on the case. She attended Panther meetings, read books that Huey assigned her, and prepared motions. When the state rejected her challenge of the grand jury, she assembled a panel of sociologists to help her strategize for the trial. This was “a novel concept. Today professional jury consultants are often used in high profile . . . cases . . . but back then the use of sociologists . . . was pioneering.”[xlv] They specifically sought ways to shape a jury to their liking, i.e., one with as many minorities as possible. Fay reached out to David Wellman, a friend and movement journalist who was working on a Ph.D. in “race relations” at Berkeley. He brought his colleagues Bob Blauner, a “confirmed Marxist,” Professor Jan Dizard, and Dr. Bernard Diamond to meet with Fay.[xlvi] Fay and her “experts” prepared hundreds of questions that Charles Garry could ask prospective jurors to root out racial “bias.” This is another example showing that outsiders or Jews will not play by the “gentleman’s rules” that bind together a homogeneous high-trust society. They literally act as a social corrosive.

Garry and Fay knew full well that their chances of winning an acquittal, or a hung jury, rested on whether they could seat Blacks on the jury. Did they really think that Blacks would judge the evidence with greater acumen and dispassion than middle-class Whites? Not bloody likely. They were well aware that minorities on juries were prone to siding with their racial brothers at the expense of facts.[xlvii] Garry wanted “to create the impression that every member of a minority group would understand his client’s perspective better than Whites, but he knew better” [emphasis added].[xlviii] He knew many Blacks in Oakland did not view the Panthers positively. He was banking on naked racial solidarity to spring a murderer and increase his own fame. Did Fay think of the implications of their strategy? Or did she simply accept the idea that Newton was justified in his actions because of White racism?

The Newton Trial

The trial began with jury selection on July 15, 1968. Judge Monroe Friedman presided. The prosecutor was the tall, courtly, almost ridiculously decent Lowell Jensen. Even Pearlman points out the contrast in style and behavior between the prosecution and the defense; it was exactly what one might expect between a WASP and a group consisting mostly of Jews.[xlix]

Security for the trial was unprecedented. Outside, Panthers and thousands of supporters marched, chanted, and screamed. Some held signs reading, “The Nation Shall be Reduced to Ashes, the Sky’s the Limit if Anything Happens to Huey.”[l] It was blatant intimidation of the judge and jury, orchestrated by the radicals, and should never have been permitted.

For three days, Fay trotted out her experts to explain to Judge Friedman how biased Whites were: Jan Dizard, Bob Blauner, Alex Hoffmann, Dr. Sanford (one of the authors of The Authoritarian Personality), Dr. Diamond, and even Hans Zeisel from Chicago.[li] It is hard to see how the affair could have been more Jewish; only Dizard and Sanford were Gentiles. The judge denied most of the defense’s requests, but did permit a longer questioning period for possible jurors. Questioning of the jury pool then took nearly three excruciating weeks. One defense strategy ironically backfired; most Blacks stated under oath that they couldn’t impose the death penalty under any conditions, and Jensen logically proceeded to exclude them, greatly reducing the number of Blacks who could sit on the jury. Both Fay and Garry had actually hoped that minorities would lie about their feelings on the death penalty so they could be seated and vote against death, if it came to that.[lii] The fact that the defense assumed they would lie, and that they were eager to profit from it, says everything we need to know about their ethics. Such are the imperatives of tikkun olam.

The jury seated five minorities, including one Black man. Jensen, fair to a fault, didn’t strive to exclude minorities just because they were minorities.

The defense put Newton, a good speaker, on the stand. He denied shooting Frey. Then, with Garry prompting him, he “talked at length . . . about hundreds of years of oppression,” over the objections of Jensen, because Judge Friedman “was fascinated” by the history lesson.[liii] Newton, of course, had no direct knowledge of “hundreds of years” of oppression; his “testimony” was totally extraneous to the case. Newton swore that the Panthers were committed to nonviolence, at virtually the same moment protestors outside were chanting, “Revolution has come – Time to pick up your gun,” and “Off the pigs.”[liv]

The Black juror, David Harper, “found himself profoundly affected” when Newton testified about racism in American society.[lv]

When cross-examined by Jensen, Newton claimed that Officer Frey had been rough with him, called him “nigger,” and pushed him; he fell, Frey pulled his gun, and Newton felt a hot flash on his stomach. He claimed he remembered nothing more.[lvi] Garry brought Dr. Diamond to the stand to testify that soldiers shot in the stomach commonly experience amnesia and unconsciousness.[lvii]

Jensen’s final remarks included a “chilling” account of the killing. Only Newton could have fired the fatal shots, he concluded. Garry then closed. He compared Newton to Christ and invoked both the Holocaust and the Armenian genocide. With tears in his eyes, he embraced Newton and implored the jury to find him innocent.[lviii]

During jury deliberations, the lone Black man and a Cuban held out for acquittal. Finally they compromised by opting for a verdict of manslaughter. It was a “stunning” victory for the defense, but it left Fay and Alex Hoffmann devastated (Pearlman speculates that Hoffmann, a homosexual, may have been in love with Newton).[lix] Newton was sentenced to two to fifteen years, under the “indeterminate” sentencing law. It was an outrageous violation of justice, worked by Jews and non-Whites at the expense of a White policeman and White society. The demoralization of White society consequent upon such a violation of justice would be hard to calculate, but surely it would have serious and long-lasting effects.

Fay began working on the appeal the next morning. Garry was busy with other cases, and handed it over to her. She would read the 4,000-page trial transcript, and eventually write a near 200-page brief arguing for a reversal of the verdict, even though historically there was very little chance for success. She threw herself into fund-raising, recruiting celebrities to lend their names to the “Free Huey” campaign, and speaking at colleges, all with her customary full-bore intensity.[lx] She also reached out to rabbis involved in civil rights work: “Fay relished making connections between her religious heritage and her current mission. In her view, Newton’s freedom should be the rabbis’ cause as well.”[lxi]

She visited Newton in prison, along with Alex Hoffmann. As his attorney, they could meet in a small room with some privacy. She felt it her duty to keep Newton’s spirits up. “She seemed . . . to be almost in love with Newton. They looked deeply at each other during her visits, sometimes touching when the guards’ attention wandered.”[lxii] They did more than touch; once “a startled guard reported seeing Stender bent down apparently engaged in oral sex with Newton.”[lxiii] It was a combination Fay couldn’t resist: her own powerful sexual appetite, a poor victim of brutish White racism, an intimate moment with a real revolutionary. Did she think of her husband? Her children? Venereal disease?

In the summer of 1969, Fay and Marvin took time for a trip to Europe and Israel. They “marveled at the transformation in Israel wreaked by the collective blood, sweat and tears of so many Jews.” A relative with an Uzi on his back showed them around what Lise Pearlman calls the “newly liberated” West Bank.[lxiv] Fay would later become “distanced” from other leftists over the issue of Palestine (they often denounced Israeli imperialism); she acknowledged the Arabs had a right to the land, but so did “the survivors of the Holocaust.”[lxv]

When they returned, Fay left Garry & Dreyfus and joined with Peter Franck (her old friend from the Council for Justice) in a new radical law “collective” in Berkeley: Franck, Stender, Hendon, Hill, & Ziegler. All but Hill were Jewish. Collectives were the new thing; they would have no distinctions in status or pay. Naturally, they would devote themselves to “Movement” work.

She finished her brief for Newton’s appeal in January 1970. In what amounted to a grand fishing expedition, she claimed, among other things, that the grand jury and the trial jury did not reflect Newton’s “peer group,” despite the fact that the prosecutor had not excluded minorities per se. Fay and Garry presented oral arguments on February 11. The appellate decision would come down in late May.

[i] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 98.

[ii] When protestor Joe Blum reached Santa Rita prison after dawn, he heard a voice call out, “Hey Joe! How many of you motherfuckers are coming out here?” It was his friend from Merritt College, Huey Newton, in prison for assault. From Hugh Pearson, The Shadow of the Panther (Addison Wesley, 1994), 73.

[iii] Arthur Liebman, Jews and the Left (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979), 68.

[iv] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 98.

[v] Ibid., 100.

[vi] Ibid., 100-01.

[vii] See Kevin MacDonald, “Jews, Blacks, and Race” here, and E. Michael Jones, The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit and Its Impact on World History, Chapter 16.

[viii] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 101-02.

[ix] Ibid., 102. Franck is Jewish; so was Axelrod.

[x] Heineman, 42.

[xi] David Horowitz, Radical Son: A Generational Odyssey (New York: The Free Press, 1997), 227.

[xii] Eric Cummins, The Rise and Fall of California’s Radical Prison Movement (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994), 97.

[xiii] All quotes from Cummins, 97.

[xiv] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 113.

[xv] Hugh Pearson, The Shadow of the Panther, 104.

[xvi] “Cleaver . . . would do more than anyone else to facilitate Huey Newton’s Black Panther Party replacing SNCC as the national symbol of Black disenchantment.” Pearson, 104.

[xvii] Peter Richardson, A Bomb in Every Issue: How the Short, Unruly Life of Ramparts Magazine Changed America (New York: The New Press, 2009), 69-70.

[xviii] Cummins, California’s Radical Prison Movement, 100.

[xix] Richardson, A Bomb in Every Issue, 121.

[xx] Ibid., 122-23. Cleaver’s warden from San Quentin had a different view of his writing. He thought it was “racist as hell, talking about the White honkies and death to the White man and that sort of thing . . . I consider[ed] it garbage, the words of a diseased mind.” (from Cummins, 98.)

[xxi] Cummins, 103.

[xxii] Cummins, 103.

[xxiii] Lise Pearlman, American Justice, 110-11.

[xxiv] Horowitz and Collier, 29.

[xxv] Pearlman, American Justice, 133.

[xxvi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 118.

[xxvii] Pearlman, American Justice, 110.

[xxviii] Pearson, 292.

[xxix] Richardson, 92-3. Stern probably knew the “French Resistance” was largely Jewish; see “Was the French Resistance Jewish?” in the Tablet: https://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-arts-and-culture/books/201308/was-the-french-resistance-jewish

[xxxi] Cummins, 113-14.

[xxxii] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 119.

[xxxiii] Pearlman, American Justice, 112, 136.

[xxxiv] Ibid., 38.

[xxxv] Ibid., 117-18.

[xxxvi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 121.

[xxxvii] Ibid., 122.

[xxxviii] Pearlman, American Justice, 151.

[xxxix] Ibid., 151.

[xl] In his book And the Walls Came Tumbling Down, Ralph Abernathy, close associate of Martin Luther King, testifies that King spent time with two women that night, neither one his wife, and beat up a third. See http://articles.latimes.com/1989-11-12/books/bk-1880_1_ralph-david-abernathy/2

[xli] After the Watts riots in August 1965, in which the Blacks of Los Angeles had destroyed much of their community, they nevertheless felt that they had “had chastised the White power structure.” Heineman, 41.

[xlii] Pearson, 154.

[xliii] Pearson, 155.

[xliv] Cummins, 121.

[xlv] Pearlman, American Justice, 161-62.

[xlvi] Ibid., 177.

[xlvii] Ibid., 217.

[xlviii] Ibid., 223.

[xlix] Ibid., 215.

[l] Pearson, 167.

[li] Pearlman, American Justice, 210-13.

[lii] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 126.

[liii] Pearlman, American Justice, 284-85.

[liv] Ibid., 286.

[lv] Ibid., 327.

[lvi] Ibid., 287-88.

[lvii] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 130-31.

[lviii] Pearlman, American Justice, 298-302.

[lix] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, xiv.

[lx] Pearlman, American Justice, 357-58.

[lxi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 143-44.

[lxii] Horowitz and Collier, 31.

[lxiii] Pearlman, American Justice, 358.

[lxiv] Both quotes from Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 150.

[lxv] Ibid., 336.

Part IV: The Collapse of the Anti-Jewish Party, 1847–1858

Part IV: The Collapse of the Anti-Jewish Party, 1847–1858