Champions of Judea: On the supplanting of British foreign policy

From Horus on Substack. Please subscribe. Excellent research.

Our last article discussed the pursuit of Jewish interests by Winston Churchill and the British ruling class. Recall that Churchill considered Jews (at least as compared to Arabs) to be racially superior and strove energetically to enable Jewish colonisation of Manchester and London as well as of Palestine. He was born in the ambit of Rothschild, de Hirsch and Cassel, and was unfailingly loyal to Zionists throughout his life, serving them with outstanding fervour. He helped bring about the Balfour Declaration. He repeated Disraeli’s dictum “The Lord deals with the nations as the nations deal with the Jews”, claiming the sanction of the Christian deity for Jewish supremacism. Churchill described his devotion to Zionism bluntly as “a question of which civilisation you prefer.”

Churchill’s anti-German beliefs were as old as his adoration of what he called the “higher grade race”. He helped cause the Great War and was thrilled by it. After Versailles, he traduced Weimar governments less frequently than he had those of the German Empire, but on occasions in the 1920s still spoke of Germany as a threat.1 On March 23rd 1933, two months after Adolf Hitler became chancellor, Churchill castigated the new Germany in Parliament for its “ferocity and war spirit, the pitiless ill-treatment of minorities [and] the denial of the normal protections of civilised society to large numbers of individuals solely on the ground of race”.2 He asserted that “The Nazis inculcate a form of blood lust in their children … without parallel … since barbarian and pagan times.”3

Portraying Germany as a military threat was, at that time, partly just a way for an unprincipled politician to attack Ramsay MacDonald, the prime minister who, though sympathetic to the Soviets, was for disarmament to facilitate peace.4 Churchill, though, was unprincipled in a consistently anti-German direction. Had he ‘warned’ about Stalin the way he did about Hitler, Churchill’s post-war reputation as the politician who ‘saw the danger’ could have been twice as great. He had been staunchly anti-communist since 1917, and until 1930 or later, “His posture toward the Soviet Union was one of consistent abhorrence.”5 Yet as the Soviet Union proceeded to amass the largest armed forces in history, Churchill does not appear to have investigated the red threat at all.6 By 1935 he was scheming with the Soviet ambassador against the British government. By the summer of 1940 he had condoned the Soviet annexation of several countries. The Soviet regime, without war as extenuation, had by 1935 already caused civilian ruin and death on a scale Hitler’s regime would never match, with immense horrors still to be inflicted. Evidently neither Churchill nor anyone else lauded for their prescience in regard to Germany had any sincere objection to dictatorships that callously maltreated civilians and used vast forces to menace their neighbours, and any historical work implying that they did must be false and exculpatory.

Jewish foreign policy

As though at the same prompting, Churchill began to campaign against Germany simultaneously with an international alliance of Jewish interests organised and led publicly by Samuel Untermyer, a wealthy Jewish lawyer from the U.S. who has also instrumental in developing and promoting Christian Zionism, a strongly pro-Israel movement. Untermyer launched a boycott which the Daily Express referred to on March 24th 1933 as a ‘Judean declaration of war against Germany’.7 ‘War’ was scarcely an exaggeration, as Zbyněk Vydra describes: “The main goal was terminating Jewish persecution by overthrowing Hitler and the boycott was meant to be one of the means of bringing Germany down on its knees.”8 In Untermyer’s words, the aim of his “purely defensive economic boycott” was to “undermine the Hitler regime and bring the German people to their senses by destroying their export trade on which their very existence depends.”9 Tolerance of their “very existence” might be resumed once they clearly signalled their compliance. At least as early as May 1933, while Soviet collectivisation killed millions, Untermyer declared that Hitler’s government was carrying out a “cruel campaign of extermination”. His accusations were repeated in private correspondence as well as in speeches, newspaper articles and open letters. He specified in 1934 that not mere expulsion from Germany but the death of all Jews “by murder, suicide or starvation” was Hitler’s “openly avowed official policy and boasted purpose”. To the suggestion of verifying whereof he spoke, Untermyer replied “I have no intention of going to see Hitler, although asked by his friends to do so.”10 Churchill similarly spoke only about Hitler, never to him. Untermyer happily visited the Soviet Union during the Great Terror; Churchill did so in secret during the war.

In Britain, a boycott of trade with German firms was begun in the East End of London by Jews descended of immigrants from the Russian Empire. Though intimidation was employed to some effect, this effort alone could not force the hand of the whole British population. Regime change could more likely be achieved by compelling nation-states to act against Germany regardless of popular wishes—the typical top-down strategy of Jewish activism aimed at recruiting non-Jewish elites—and of that aim Untermyer’s international campaign stood a better chance. He first launched the American League for the Defense of Jewish Rights, but was persuaded later in 1933 to change the name to the Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi League to Champion Human Rights in order to attract non-Jewish support. According to Richard Hawkins, “In early November 1934, the NALCHR announced that a world conference would begin on November 25 in London. Its aim was to intensify and coordinate the boycott of Germany.” As Hawkins describes, the World Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi Council to Champion Human Rights (WNSANCHR) was established as a result.

“The conference also resulted in the establishment of a British Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi Council (BNSANC) with Sir Walter Citrine, the general secretary of the British Trades Union Congress, as president. … The activities of the BNSANC appear to have gone largely unreported apart from a successful demonstration of as many as twenty thousand and a meeting in London’s Hyde Park joined by many thousands more on October 27, 1935. It was addressed by prominent British politicians and academics from across the political spectrum including Eleanor Rathbone MP, Clement Attlee MP … Citrine, Professor JBS Haldane and Sylvia Pankhurst.”

Hawkins must imagine the political spectrum to run only from socialists to communists, but regardless, the Council would soon become remarkably non-sectarian in that regard. Though he says they went largely unreported, Hawkins himself mentions that the state-controlled BBC broadcast the Council’s addresses.11

The burgeoning influence, assisted by the BBC, of socialists like Attlee and Haldane caused dread to British conservatives including Harold Harmsworth, the first Viscount Rothermere, who owned newspapers including the popular Daily Mail and who had opposed universal suffrage and the growth of the Labour Party.12 Rothermere supported revision of the treaties imposed on Germany and the other defeated states after the Great War. He was also sympathetic to Benito Mussolini’s fascists and Hitler’s National Socialists for their fierce opposition to the many attempts at communist revolution in Italy and Germany. In January 1934, he began supporting the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in Mail editorials. Rothermere was particularly alarmed at Stafford Cripps’ communist-friendly Socialist League, which campaigned for Labour’s next government to grant itself the power to rule by decree and prohibit all opposition.13 With the Socialist League intact and growing, Rothermere nevertheless ceased to support the BUF in July 1934. According to Paul Briscoe, “Jewish directors of Unilever … decided to present … Lord Rothermere, with an ultimatum: if he did not stop backing Mosley, they and their friends would stop placing advertisements in his papers. Rothermere gave in.”14 In November 1933, Untermyer had written that “A properly carried out boycott will cause Germany´s economic collapse within a year.” Shortly after, Pinchas Horowitz, a prominent member of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, wrote that “Once the sixteen million Jews inhabiting the world stop buying German goods, they will represent a power which no country will be able to ignore.”15 Presumably, as Jews were relatively small in number and spread across many countries, neither Untermyer nor Horowitz seriously estimated their power as consumers so highly; the power which no country would be able to ignore more likely referred to the ability to coerce pezzonovantes like Rothermere to help ensure that Britain and other powerful states would prioritise international Jewish interests over those of their own people. Mosley, who strove to prevent war, would never have been anything other than a hindrance to “causing Germany’s economic collapse”.

Pinchas Horowitz was also a leading member of the Jewish Representative Council for the Boycott of German Goods and Services (JRC), founded in November 1933. The JRC was separate from the BoD though they had much commonality in membership. Neville Laski, the Board’s president, refused the JRC’s demands to involve his organisation officially in the Jewish boycott, arguing that such a move would likely provoke Hitler’s government to take repressive measures against Jews in Germany.16 This was consistent with the cautious stance taken by the German equivalent of the Board, the Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith.17 Whatever Untermyer said about “terminating Jewish persecution”, he and associates like Rabbi Stephen Wise led the faction prepared to aggravate such persecution in pursuit of “overthrowing Hitler”. As Zionists, they likely found provocations of Hitler desirable. Certainly Untermyer seemed to regard his Jewish opponents in America with contempt, saying in December 1937:

“The wave of world-wide anti-Semitism, led and encouraged by Germany, that is inundating our country should serve only to make us more race conscious, tie us closer together and confirm us in our determination to combat and overcome by every means in our power the vast propaganda of this world-bully and braggart and the forces of evil that inspire it. There are still too many turn-coats, hyphenated Jews and apostates in our ranks. The sooner we expose them and rout them out, the better it will be for our welfare and self-respect. They are an undiluted liability.”18

Neville Laski’s reticence toward the overt participation of the Board of Deputies in Untermyer’s boycott also derived from the value he placed on the Board’s close relations with the British government and civil service. The historians who have written on the boycott mostly treat as a failure or a mistake the Board’s declining to join officially (though individual members were free to participate), but good relations with the likes of Robert Vansittart, the acutely anti-German head of the Foreign Office, were arguably more valuable. According to Laski, at a meeting in October 1934, Vansittart, referring to Untermyer and the American Jewish Congress (AJC), said that

“the aggressively Jewish, flamboyant and narrow character of the anti-German propaganda carried on by certain Jewish quarters in America was having results which were very nearly provocation of anti-semitism on a large scale. … He said that he approved of the use of an economic weapon against Germany, but he did not approve of a flamboyant user of such a weapon.”19

Vansittart thus advised his allies on public relations, the better to achieve their shared aims. In 1936, as the World Jewish Congress was being founded (mainly by AJC members at first) with aims including “to coordinate the global economic boycott of Germany”, Laski, “who had originally been just cautious, changed his opinion within a single month towards a complete refusal and did his best to prevent participation in the WJC.” According to Vydra, the prevailing view among the Board of Deputies was that “the Congress would strengthen the boycott movement, but the BoD´s participation would lead to the loss of influence on the British government.”20 Most historians are militantly incurious about how the Board, representing less than half a percent of the British population, came to have such influence.

Jewish domestic policy

Vydra remarks that “[t]he Jewish boycott of Germany was an international activity and can be understood as a type of Jewish foreign policy.”21 Gentile foreign policy was found wanting. Intercession (stadlanut) had been enacted by the Russo-Jewish Committee and Lord Rothschild since the 1880s. The Jewish elite in Britain had also founded the Conjoint Committee for such work. While men like Vansittart and Churchill worked to align British foreign policy with “Jewish foreign policy”, their colleagues did likewise in domestic matters, virtually without resistance. The British Union of Fascists, however unsuited to the role, appears to have been the only vehicle of any size for opposing the usurpation, and thus was targeted for violent suppression. On 4th October 1936, the BUF staged a lawful, police-escorted demonstration through several sites in East London, an area in which Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe had concentrated, in which the unofficial, militant boycott of Germany had begun and in which British people were confronted by immigrant hostility exemplified by the violent crime operation led by Jacob Comacho (alias Jack Comer or Spot). As the police escort attempted to clear illegal blockades in Aldgate, they were assaulted by masses of armed Jews, Irish and communists. Comacho and his associates were leading figures in the assault. Jews organised under the Jewish People’s Council Against Fascism and Anti-Semitism. The communists were mainly from the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), which took orders from the Soviet Union via the Comintern. The ‘Battle of Cable Street’ was the largest of many such assaults on the BUF in the 1930s. The aggressors were rewarded with legislation within two months: a new Public Order Act which impaired the BUF’s ability to demonstrate.22

The Board of Deputies did not at first openly encourage anti-fascist aggression. As Daniel Tilles says, “much of the Board’s anti-fascist activity, for … good reason, took place privately and remained unpublicised.”23 In July 1936, a deputation from the Board, including Neville Laski and vice-president Robert Waley Cohen, expressed sympathy for Jewish violence against the BUF and prevailed on Simon to punish “those preaching hatred”.24 John Simon’s Act, passed in December that year, was “influenced by the personal intervention of Harold Laski” (Neville’s pro-Soviet brother) and “made the police act with even greater intensity” against the BUF.25 Let us assume that the hatred preached was so abominable as to justify bricks flung at British bobbies by gangsters, else we risk the conclusion that the deputies sought special treatment and power for the higher grade race.

The Board had begun to co-opt anti-fascist militancy before the assault in Aldgate, “establishing a body to direct defence policy in mid-1936, the Co-ordinating Committee (CoC—known from late 1938 as the Jewish Defence Committee).”26 Late in that year, “Sidney Salomon, the secretary of the CoC, in an interview with the Evening Standard, absolved his thugs of blame for their aggression, arguing that it was ‘not human nature … to stand calmly by while Blackshirts shout insults.’”27 Herbert Morrison, leader of the London County Council and a senior figure in the Labour Party, which affected to exist for the benefit of British workers, met in secret with Neville Laski and Harry Pollitt, leader of the CPGB, in October 1936 to co-ordinate the terrorism they mutually supported.28 By March 1937, Neville Laski was satisfied that condoning violence would not lose him politicians’ support: “in contact with the Home Office to discuss anti-Jewish meetings, [Laski warned] that ‘any self-respecting Jew in the crowd would have the greatest difficulty in restraining himself, not only vocally, but even physically.’” He also urged police to collaborate with Jewish and communist infiltrators or invaders starting fights at BUF meetings.29 Newsreel producers already routinely used misleadingly-edited footage of such fights to portray the BUF to the nation as the instigators.

Spreading dread

With the most avid opponents of hostility to Germany corralled by state suppression and terrorism, successive British governments, notwithstanding their Home Secretaries, remained an obstacle to the full adoption of “Jewish foreign policy”. Under MacDonald and Stanley Baldwin, peace with Germany continued, and Neville Chamberlain intended the same. Winston Churchill followed his aspersions about “war spirit” and “blood lust” with a fear campaign about Germany’s military strength. “As 1934 progressed Churchill developed an important subsidiary theme to disarmament: the growth of German air power”, according to David Irving, who continues:

“‘I dread the day,’ he told the House on March 8, ‘when the means of threatening the heart of the British empire should pass into the hands of the present rulers of Germany.’ Such melodramatic statements were typical of the debating stance that Churchill would adopt over the next five years. Sir John Simon predicted in cabinet on March 19 that Hitler would move east or into territories of German affinity like Austria, Danzig and Memel. His colleagues were unconvinced that Hitler harboured evil designs on the empire, and rightly so. We now know from the German archives that even his most secret plans were laid solely against the east. In August 1936 he would formulate his Four Year Plan to gird Germany for war against Bolshevist Russia; and not until early 1938 did he order that Germany must consider after all the contingency of war with Britain—a contingency which, it must be said, Mr Churchill had himself largely created by his speeches.”30

Churchill “found that Britain’s weakness in the air was a popular theme, particularly among leading London businessmen. Their doyen Sir Stanley Machin invited him to address the City Carlton Club on it. He developed his campaign on the floor of the House, in newspaper and magazine articles, and in BBC broadcasts too.”31

Churchill used Parliamentary privilege and his high security clearance to publicise statistics, and alarming interpretations of them, on behalf of a network of anti-German civil servants and intelligence agents led by Robert Vansittart, head of the Foreign Office. On 9th November 1933, the Committee of Imperial Defence had “decided that a body should be set up to determine Britain’s worst defence deficiencies. That body, which became the DRC, was approved by the Cabinet on 15 November” but “held its first meeting on 14 November, the day before it was formally constituted by the Cabinet.”32 The Defence Requirements Committee was “the body whose decisions largely determined the path that British strategic defence policy took in the years until 1939.”33 It was a vehicle for Vansittart and Warren Fisher, his equivalent at the Treasury, to wage institutional war against the Air Ministry which was “[i]n theory… the sole body responsible for the co-ordination and analysis of information on the German air force” and which insisted on reporting what it found.34 As Wesley Wark describes,

“Despite the fact that no concrete intelligence had reached the air ministry during the DRC’s term, the committee nevertheless found itself preoccupied by the question of the future rearmament of Germany, especially in the air. Pushed by Vansittart, the DRC accepted, without conviction, the estimate of five years as the time it would take Germany to rearm, and adopted this as their deadline for British defence planning. Germany was fixed, using Warren Fisher’s terminology, as the ‘ultimate potential enemy’. When the chief of the air staff presented a very modest programme for the RAF to the committee, both Vansittart and Fisher threatened that they would not sign the report.”35

The moderation of the air staff provoked Vansittart to bypass them. “The clash of political and military intelligence in the DRC had encouraged the central department of the Foreign Office to begin drawing up their own appreciations of the German air force.”36 Ralph Wigram, the head of that department, supplied Churchill figures until his death in 1936.37 Another supplier was Desmond Morton, formerly of the Secret Intelligence Service and in 1934 the head of the Industrial Intelligence Centre of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Morton brought to Churchill’s home “secret files which the Prof. [Frederick Lindemann] illicitly photocopied for Churchill.” Morton’s figures only spoke of numbers of planes and “omitted any consideration of quality or range”.38 Churchill’s rhetoric aimed at maximising alarm: “‘Germany has already, in violation of the Treaty, created a military airforce which is now nearly two-thirds as strong as our present home defence airforce.’ By the end of 1935, he warned, Hitler would match Britain’s airforce; by 1936 he would overtake it—such was Churchill’s claim.” Irving paraphrases Churchill: “[I]f both countries continued to rearm at their present rate, in 1937 Germany would have twice the airforce Britain had.” He continues:

“It is plain from the record of November 25th that the cabinet was concerned about the effect of Mr Churchill’s brash campaign on their delicate relations with Germany. Hoare felt they must make clear to the world that his ‘charges were exaggerated.’ Chamberlain expressed puzzlement that they themselves had no information backing Churchill’s claims. … [T]he captured files of the German air ministry reveal both his statistics and his strategic predictions to have been wild, irresponsible, exaggerated scaremongering, delivered without regard for the possible consequences on international relations.”39

Vansittart was aided by Reginald Leeper who became head of the Foreign Office news department in 1935. According to Richard Cockett, “Leeper shared the views of Sir Robert Vansittart on foreign policy and in particular his attitude to Germany.”40 Leeper sought “willing collaborator[s]” among journalists

“to further the aims and policies of the Foreign Office. He realized that with a certain degree of openness and flattery diplomatic correspondents could be welded into a cohesive body who could be relied upon always to put the Foreign Office point of view in the press. [He] built up a set of diplomatic correspondents … loyal to him.”41

The main enticement for correspondents was being shown confidential Foreign Office documents. “[T]he more correspondents were let into the News Department’s confidence, the more willing they would be to adopt the Foreign Office view.” Leeper’s “tame pets” repeated the Foreign Office’s views under their own names.42 At least one of the “most privileged diplomatic correspondents”, Norman Ewer of the Daily Herald, was a spy for the Soviet Union.43

In March 1935, Vansittart leaked the fact that Hitler had privately claimed to John Simon that his Luftwaffe, forbidden under Versailles, had already reached parity with the Royal Air Force.44 Leeper then fed out a more alarming story in April, and Churchill spoke of it as “official” in Parliament.45

Leeper’s team overlapped with Vansittart’s. According to Cockett,

“they used the News Department to give out news of conditions in Germany, statistics of German rearmament, reports of German concentration camps to enhance this pessimistic view of Germany—the leak to the Daily Telegraph in 1935 was supposed to contribute to this general picture. Vansittart was particularly free with his confidences and encouraged Leeper to take the same attitude in the pursuance of their campaign against appeasement. Ian Colvin relates how ‘Rex Leeper sometimes came upon Vansittart in his room at the FO in full conversation with Winston Churchill.’ The excuse Vansittart gave to Leeper for communicating confidential information to a mere MP was that ‘it is so important that a man of Churchill’s influence should be properly informed’ and so he was quite content to ‘tell him whatever I know’.”46

Intelligence sources

As Wark says, “The best intelligence which the [Secret Intelligence Service] gained on German air force developments was obtained through contacts with foreign secret services and through the exploitation of dissident German sources.”47 On the basis of such sources, some of whom approached him directly, from February 1936, Vansittart formed his own intelligence network, “separate from the SIS and the Foreign Office”.48 According to Cockett,

“Vansittart was… particularly open in his communications with FA Voigt of the Manchester Guardian. Indeed, Voigt was a key member of Vansittart’s shadowy ‘Z Organization’, an intelligence service run principally for his own benefit to keep him informed of developments inside Nazi Germany. It was run with the co-operation of the head of the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), but otherwise was run clandestinely – unknown to the rest of the staff at SIS headquarters in London.”49

According to Gill Bennett, the Z Organisation was set up by Hugh Sinclair, head of SIS, and assigned to Claude Dansey, who “ran his own small staff, including Jewish émigrés and other exiles, and supposedly communicated with SIS only through [Hugh] Sinclair, although the evidence suggests that Morton too received information directly from Dansey.”50

Churchill’s intelligence network also included Jewish émigrés like Jurgen Kuczynski, a spy for the Soviet GRU, and Leopold Schwarzschild, a journalist and publisher, whom Churchill called “two German refugees of high ability and inflexible purpose”.51 Using information from Kuczynski was especially absurd:

“After publishing an anonymous article in Brendan Bracken’s The Banker in February 1937 with tongue-in-cheek ‘calculations’ of Hitler’s annual arms budget, he had been contacted by ‘certain circles, and these he had ruthlessly milked of both funds for the party coffers and secret information for the Soviet Union. These circles, he said by way of identification, were those that came to power in 1940 ‘with the overthrow of Chamberlain.’

… Kuczynski also drafted a blimpish brochure on Hitler and the Empire, to which an R.A.F. air commodore wrote the foreword. ‘I chose the pen name James Turner,’ he wrote. ‘The whole thing was a rather improbable romp.’ Turner’s line was, he chuckled, to deny any personal dislike of fascism—that was a matter for the Germans alone — ‘If only it were not such a danger for the British empire.’”52

Kuczynski and Swarzschild may have already been sources for the Z Organisation or Morton’s Industrial Intelligence Centre at the CID (or both). As Wark describes,

“The IIC was created as a secret unit in 1931 to collect and evaluate information on industrial war planning in foreign countries. … Their sources included material from industrial publications, statistics from the board of trade and department of overseas trade, Foreign Office reports, information volunteered by British industrialists and whatever covert material was supplied by the Secret Service.”

For reasons unexplained, “At first the IIC concentrated on Russia but soon turned its attention to the German aircraft industry.”53

One “British industrialist” who volunteered information was Sir Henry Strakosch, a Jewish financier from Austria who, according to David Lough, was another of “the small group of experts who had been feeding Churchill confidential information about Germany’s armaments expenditure.” Of Strakosch’s expertise, Lough says that “As chairman of Union Corporation, the South African mining business, Strakosch passed on confidential details of the raw materials which his company was supplying to the German armaments industry.”54 The German armaments industry must have been awful enough to alarm Strakosh but not quite so terrible that he stopped contributing to it. As Irving describes,

“When the air staff issued a secret memorandum on November 5, 1935 — based, we now know, on its authentic codebreaking sources — stating firmly that the German front line consisted of only 594 planes, Churchill sent an exasperated letter to the Committee of Imperial Defence: ‘It is to be hoped,’ he wrote, ‘that this figure will not be made public, as it would certainly give rise to misunderstanding and challenge.’”55

Friendship with Strakosch became highly beneficial to Churchill and the anti-German front. In severe financial difficulty in 1938, Churchill told friends he would leave politics and put his mansion Chartwell up for sale. Strakosch agreed to pay off the debts (about £18,000 according to Irving and Lough). “Chartwell was withdrawn from the market, and Churchill campaigned on.”56 Lough stresses that there was no quid pro quo with Strakosch (other than membership of Churchill’s dining club). I find no evidence contradicting Lough here. Strakosch’s motive appears to have been to keep Churchill, perhaps the most well-placed activist for the cause, in politics to “campaign on” against “misunderstanding and challenge”. As Lough says of their collaboration, “Sir Henry … regarded Churchill as the one politician in Europe with the vision, energy and courage required to resist the Nazi threat.”57 Strakosch loaned another £5,000 to Churchill in 1940 and left Churchill £20,000 when he died in 1943.58

The Focus

Cockett describes how “Leeper and Vansittart enlisted [Churchill] in their campaign against Germany” as he “could be thoroughly relied upon to use their information in the way that they wanted”. Leeper

“visited Churchill at his home at Chartwell on 24 April 1936 to encourage him to try and bring together all the various groups who were already concerned about the German danger. This meeting was the genesis of the anti-Nazi council which became known as the Focus Group. This duly tried to rectify what Vansittart had identified as the crucial flaw in Britain’s state of readiness: ‘the people of this country are receiving no adequate education — indeed practically no concerted education at all — against the impending tests’ … ”59

Other than this “genesis” at Chartwell, the Anti-Nazi Council was already the British branch of Untermyer’s World Non-Sectarian Anti-Nazi Council for Human Rights. As Richard Hawkins describes,

“In April 1936, Winston Churchill joined the WNSANCHR. … In July, the Board of Deputies of British Jews created a secret fund to support anti-Nazi groups including the WNSANCHR. At a meeting on October 15, the WNSANCHR, at the suggestion of Churchill, decided to establish a Focus in Defence of Freedom and Peace movement. The Focus helped revive Churchill’s political career. As Eugen Spier later observed, ‘Later on it was easy to forget the part [the Focus] played in creating a platform for Winston Churchill at a time he was in the political wilderness.’”60

The Focus served as an information exchange, a network of support and a fountain of money for the anti-German campaign of which Churchill was the most valuable figure. Yet despite including prominent politicians, civil servants, businessmen and journalists, few of whom were abashed about their stance on Germany, Churchill was no more keen for the Focus to be a matter of public discussion than he was the real size of the German air force. To enable individuals with contrasting affiliations to join discreetly, the group had a loose structure, avoided formal membership and only staged events under other names.61 Eugen Spier, a Jewish immigrant from Germany and one of the founders and main funders, wrote a book on the career of the organisation, but did not have it published until 1963. Irving says that “Churchill pleaded with him not to publish it during his lifetime.”62 Court historians still frown at our disrespect for the great man’s privacy.

Churchill “wryly recognised who was behind this body. ‘The basis of the Anti-Nazi League,’ he would write later in 1936 to [his son] Randolph, misquoting its proper title, ‘is of course Jewish resentment at their abominable persecution.”63 Jewish resentment may have been a motivation, but the wealthy, well-connected Jews in the “League” were not under persecution and, as noted, the international effort of which they were part intruded upon the cautious practices of the Jewish organisations in Germany. The Focus’s aims were the same as those of Untermyer and the World Jewish Congress: Germany must overthrow Hitler or be destroyed. In Spier’s words, “we had to prove to Britain and the world that for us there could be no peace with the Nazi regime.”64 Whether the struggle was really for survival or supremacy, no cost was too great.

Bribery

Another “basis of the League” was Czech bribery. The recipients tended to be unapologetic. As Irving says,

“Europe was awash with secret embassy funds. … The Czechs were most prolific. … When Robert Boothby, once Churchill’s private secretary and now a member of his Focus, was later obliged to resign ministerial office over irregularities involving Czech funds and a certain Mr [Richard] Weininger, he advised the House, as an MP of sixteen years’ standing, not to set impossible standards ‘in view of what we all know does go on and has gone on for years.’”65

Weininger, a wealthy Jewish immigrant, was working mainly for his own benefit.66 Jan Masaryk was the main conduit for Czech government bribery and a friend of Churchill. Reginald Leeper and Henry Wickham Steed, the Focus’s most committed journalist, were two payees.67 Sir Louis Spears MP was given regular cash and a lucrative directorship of a major Rothschild-controlled Czech industrial firm at the behest of Edvard Benes.68

Communist sympathisers

The Czech government was headed by Benes and had formed an alliance with the Soviet Union in 1935. The Soviets were permitted to use Czech airbases against Germany and Benes wholly trusted that they would provide sizeable forces in case of war; the Soviet Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov, encouraged his trust.69 The Focus’s aims dovetailed with Litvinov’s foreign policy and the aims of the Comintern. The above-mentioned Robert Boothby was a co-founder of the Popular Front which lobbied for pro-Soviet policies from 1936 until being assumed into Churchill’s wartime government. The Focus also included former Labour minister Hugh Dalton MP, an apologist for the Soviet dictatorship since its founding.70 Focus members Clement Attlee, leader of the Labour Party, leftist Tory MP Harold Macmillan, ‘peace’ activist Norman Angell and Liberal Party politician Violet Bonham-Carter, an old friend of Churchill, wrote for The Future, a magazine published by Willi Münzenberg, a German communist who specialised in creating pseudo-independent organisations to enable celebrity intellectuals like Angell to deniably support the Soviet Union.71 The launch of The Future was funded by Munzenberg’s comrade Olof Aschberg, a Jewish banker from Sweden who had helped launder money for the Bolshevik regime after its repudiation of foreign loans and seizure of private assets. The editor was Arthur Koestler, also of Jewish ancestry, who had recently resigned as a Comintern agent when The Future launched.72

Zionists

Alongside servants of the Comintern, the Focus was populated by Zionists, Jewish or otherwise. A leader of Anglo-Jewry and member of the Focus along with his brother Robert was Henry Mond, the 2nd Baron Melchett, who had helped finance Pinhas Rutenberg’s plan for irrigation and electricity generation in Palestine (Rutenberg’s company was granted a monopoly on generation over most of Palestine in 1921).73 In this effort Mond joined Edmond de Rothschild, the primary financier of Jewish settlement in Palestine (and Rutenberg’s scheme), and Edmond’s son James de Rothschild, a family friend of Churchill and a member of the Focus with his cousin and wife Dorothy. Churchill supported Rutenberg’s project while he was Colonial Secretary from 1921-22 just as he consistently supported the greatest possible Jewish immigration into Palestine throughout the 1920s and 30s (expressly to make Jews the majority there). Rutenberg was a leading Zionist activist closely associated with Churchill’s friend Chaim Weizmann as well as David Ben-Gurion and Vladimir Jabotinsky. Weizmann and Ben-Gurion became Israel’s first president and prime minister in 1948. Jabotinsky was a Zionist militant and anti-British agitator who founded Irgun, members of which murdered British officials and servicemen in Palestine after the war.

Secret funding

Copious funding was available to the Focus. The “secret fund” Hawkins mentions was administered by Robert Waley Cohen, vice-president of the Board of Deputies of British Jews. As Robert Henriques describes, “Bob” was one of the leaders of Anglo-Jewry, for whom there was a need “to find a platform which would enlist the whole-hearted support of the greatest possible number of Gentile friends.” He continues:

“Every week Bob and a few other leaders of Anglo-Jewry met at New Court to plan a form of defence against anti-Semitic propaganda. In June, Bob, and several others had an interview with the Home Secretary and returned with the assurance that the Government would do everything in its power to arrest what it acknowledged to be “a growing evil”.74

The other leaders go unnamed. Henriques continues:

Churchill “enlisted many eminent men in his ‘Defence of Freedom and Peace’ movement, and this formed a nucleus of sympathetic, liberal, non-Jewish opinion with which the Anglo-Jewish leaders could co-operate. While Jewish Defence was continued by the Board of Deputies with direct propaganda which probably did more to reassure British Jews than to combat the infiltration of Nazi doctrine, it was decided at New Court to raise a secret fund, initially of £50,000, which would work with the sympathetic non-Jewish organisations as well as with the Jewish Telegraph Agency, the latter providing the hard facts of Nazi atrocities which were so seldom reported in the press. Bob agreed to raise, control and administer this fund. It was started with a dinner party at Caen Wood Towers on 22nd July, from which over £25,000 was immediately subscribed, and the balance promised. Bob insisted from the start that the Jewish defence movement must concentrate on attacking Nazi philosophy and its denial of human rights, rather than on the direct refutation of anti-Semitic propaganda. … [H]e insisted that propaganda should be directed against ‘pursuing peace without caring for freedom and justice’ — a summary of the British policy of appeasement.”75

Cohen, like Spier, took as read that “Jewish defence” entailed using one gentile nation-state to impose Jewish values and interests on another.

As David Irving says, £50,000 “was a colossal sum for such an organisation to butter around in 1936 — five times the annual budget of the British Council”, and it was only “initially” £50,000.76 Cohen, thanks in part to his means, took charge of the Focus, as Henriques describes:

“[T]he ‘Defence of Freedom and Peace’ movement was publishing a series of pamphlets explaining what Nazi-ism meant and refuting the belief in the country that it had its legitimate aspects. Each pamphlet was read in manuscript by Bob and usually edited and amended profusely. Even Winston Churchill was not exempt; and one of his articles entitled ‘The Better Way’, which he sent to Bob in draft, was returned to its author with copious alterations, all of which were accepted. Soon the ‘Defence of Freedom and Peace’ movement, whose secretary was AH Richards, began publication of a journal known as Focus on which Wickham Steed and Bob — the latter described as ‘the veritable dynamic force of Focus’ — were Churchill’s main lieutenants.”77

News media

Under the pretext of securing “human rights” and combatting “anti-Semitic propaganda”, the Focus strove to pressure the news media into a belligerent stance toward Germany:

“To administer the ‘secret’ defence fund, Bob employed HT Montague Bell, recently retired from the editorial chair of The Near East, who was very largely engaged in drafting letters to the press and providing the necessary facts, for eminent people to compose their own letters in refutation of the very considerable correspondence published by most of the national newspapers excusing Fascism and even advocating it, including sometimes its anti-Semitic aspects.”78

The Focus also worked to co-ordinate ostensibly separate media organisations toward a single aim:

“While Montague Bell was arranging the publication of a series of so-called ‘Vigilance’ pamphlets, written by Colin R Coote, then a leader-writer of The Times, and other well-known journalists, Bob was personally interviewing various Tory Members of Parliament, including Harold Macmillan, Douglas Hacking, and Sir Waldron Smithers. Negotiations which had begun in 1937 between Bob, Professor Gilbert Murray and Sir Norman Angell led to the formation in 1938 of the Focus Publishing Company which took over Headway, the publication of the League of Nations Union. Meanwhile, Bob’s fund was being used to sponsor a large number of small, independent enterprises whose operations were co-ordinated by Montague Bell, now reinforced with an assistant and a secretariat.”79

With Churchill, Macmillan, Boothby and others being sitting Conservative MPs, the Focus’s secretiveness was prudent as, according to Eugen Spier, “the policy of the new Headway would be to turn out the Conservative government.”80

Both the Focus and the Board of Deputies appear to have been subsidiary, at least financially, to the unnamed leaders of Anglo-Jewry who met at New Court and initiated the “secret fund”:

“By tremendous efforts … Bob raised further gifts to the Fund to keep pace with its expenditure. It was found that the work of the Fund inevitably overlapped the official defence work of the Board of Deputies. Accordingly a very substantial annual sum was paid by the Fund to the President of the Board (Neville Laski, KC) so that he could temporarily sacrifice his legal practice and devote himself wholly to the co-ordination of Jewish defence.”81

Under the threat of an advertising boycott, potential adversaries of the Focus like Lord Rothermere, owner of the Daily Mail, had already been rendered compliant. Lord Beaverbrook, main owner of the Daily Express (in which Rothermere had a large stake too) was susceptible to the same menaces, and, though at times privately sympathetic to Germany, he printed what he thought good for business. His Express headline from March 1933, ‘Judea Declares War On Germany’, preceded an article lauding Judea for doing so. Beaverbrook was also a friend of Churchill, Vansittart and Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador.

Perhaps the most consequential of the Focus’s activities was described by Eugen Spier to Churchill privately in June 1937:

“It is one of the objects of the Focus to provide its members, and you most of all, with just those facilities which a party machine provides, publicity by public meetings, through the press and our publications. The Focus is steadily growing; its audiences daily become larger, its backing ever more forceful, with the support of some of the most important people in the country.”82

With its forceful backing, the Focus did attract the support of important people. It could also make mediocre people seem important. By late 1936, “The editors of the influential weekly journals The Spectator, New Statesman, The Economist and Time & Tide were wooed and won: Wilson Harris, Basil Kingsley Martin, Lady Rhonda, Harcourt Johnstone.” They were joined by “Sir Walter Layton and AJ Cummings, chairman and chief commentator of the News Chronicle, as well as Lady Violet [Bonham-Carter] and two BBC executives.”83 The BBC, as noted, had already helped publicise the Focus’ precursory demonstrations. They also gave Churchill respectable amplification for his ‘warnings’ about Germany as early as 1934.84 Henry Strakosch and Churchill’s friend Brendan Bracken jointly owned half of The Economist anyway.85 Walter Citrine was already a director of the Labour-aligned Daily Herald. The Daily Mirror was vehemently anti-Hitler without prompting from the Focus. There were others whom the Focus left alone as they were already model citizens: the Express’ cartoonist David Low, who specialised in ridiculing his enemies, or his counterpart at the Mirror, Philip Zec, who specialised in dehumanising them. Low was a supporter of the Soviets (except when they allied with Germany) and Zec was a director of the Jewish Chronicle, the grandson of a rabbi and son of an immigrant from Odessa.

According to Irving,

“At Waley-Cohen’s request Brendan Bracken released German-born Werner Knop, who had been foreign news editor of his Financial News and Banker since 1935. The Focus set him up in an office in the fountain yard of one of the ancient Inns of Court near Fleet-street. Knop’s ‘front,’ Union Time Ltd, disguised as a press agency, was funded ‘by a group of British businessmen and newspaper editors’.”86

Marcus Bennett describes Union Time as “a front for various German emigres working across various professional fields to encourage anti-Nazi opinion in Britain and combat Nazi propaganda in general.” He continues: “It was Union Time Ltd which had camouflaged, among many others, the activities of [Hilde] Meisel, who approached … [Labour MP George] Strauss asking for money to murder Hitler. Strauss sent her to the City of London to meet Werner Knop. … Knop granted her the necessary financial support.”87

The Focus also benefited from partnership with a real press agency, Cooperation Press Service. According to Lough, Cooperation Press Service, “founded by Dr Imre Revesz, a Hungarian Jew … specialized in distributing articles written by European politicians across a network of 400 newspapers in seventy countries on the Continent. Cooperation had started in Berlin before Hitler’s rise to power, then moved to Paris just before a raid on its offices by the Gestapo.”88 Revesz (alias Emery Reves) offered Churchill a much wider readership and larger fees for his newspaper articles by syndication. He did the same for Clement Attlee, Tory ministers Anthony Eden and Alfred Duff Cooper, and anti-German politicians across Europe including Leon Blum, a central figure in the Popular Front.89

Vansittart-Litvinov

The Focus bound several forces into one fascio: journalists, Foreign Office men, the Popular Front, industrialists, Czech hirelings, Disraelite Tories, Zionists and mainstream Anglo-Jewry, all drawing upon Cohen’s secret fund and serving the same purposes as the international alliance headed by Samuel Untermyer and his colleagues at the World Jewish Congress. It also complemented the work of leading civil servants. The Foreign Office, as we have seen, had been committed to anti-German policies long before Hitler became Chancellor, and before Germany had done anything more threatening than condemn the Treaty of Versailles, Vansittart collaborated with the Soviet government against his own. The diaries of Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador, were edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky, who says that

“In going about his ambassadorial duties in London, Maisky studiously followed the lead of [Maxim] Litvinov, who had spotted the Nazi threat as early as 1931. However, it took Litvinov almost a year to convince Stalin that Hitler’s rise to power meant that ‘ultimately war in Europe was inevitable’. The formal shift in Soviet foreign policy … towards a system of collective security in Europe and the Far East … occurred in December 1933…

Vansittart, the permanent undersecretary of state, was the advocate of such ideas in Britain. … Britain could preserve a local balance of power in both Europe and the Far East by allying with the Soviet Union, which could place a check on both Japanese and German expansion. … He … gravitated towards European security based on the pre-1914 entente of Britain, France and Russia.”90

The balance of power policy was established as Foreign Office doctrine by Eyre Crowe, Arthur Nicolson, Charles Hardinge and other favourites of King Edward VII.91 Maurice Cowling says that Vansittart “advocated a Russian alliance with France, British co-operation with Litvinoff and tripartite firmness towards Germany.”92 He “treated the Franco-Soviet alliance as non-negotiable.”93

Russia had ceased to be a state in 1917. The Russian monarchy had been usurped, the monarch murdered, the alliance with Britain repudiated in bello [in war] and the empire refounded as a Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, but these were, apparently, not too much of an interruption for the entente of 1907 to be considered obsolete. Nor were the Bolsheviks’ brazen hostility toward and attempts to undermine the British Empire, which continued under the Comintern until 1943 (and in other forms afterward), nor that the crimes of Stalin’s regime exceeded even those of Lenin’s. Stalin himself was leader the Soviet attempt to impose “collective security” on Poland in 1920. Regardless, the school of Eyre Crowe merged happily into that of Meir Henoch Wallach-Finkelstein (‘Litvinov’ was an alias). Gorodetsky says plainly (and approvingly) that Vansittart was an “ally” of Maisky.94

Thus the Focus did not recruit men like Vansittart but rather teamed with them. As mentioned, Rex Leeper introduced Churchill to the Anti-Nazi Council in April 1936. In the previous year, as Gabriel Gorodetsky describes,

“Vansittart assisted Maisky in setting up a powerful lobby within Conservative circles. … Maisky was further invited to a dinner en famille at Vansittart’s home [in June 1935], where he met Churchill. ‘I send you a very strong recommendation of that gentleman,’ wrote Beaverbrook to Maisky. … Churchill indeed told Maisky that, in view of the rise of Nazism, which threatened to reduce England to ‘a toy in the hands of German imperialism’, he was abandoning his protracted struggle against the Soviet Union, which he no longer believed posed any threat to England for at least the next ten years. He fully subscribed to the idea of collective security as the sole strategy able to thwart Nazi Germany.”95

Churchill frequently referred to his desire to ‘encircle’ Germany again. At a royal reception in November 1937, he had made a show of spurning Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German ambassador, and telling Maisky “I’m wholly for Stalin.”96 In March 1938 he told Maisky that “I am definitely in favour of Stalin’s policy. Stalin is creating a strong Russia. We need a strong Russia and I wish Stalin every success.”97 By May 1938, during the first Czech crisis, he had sunk as far as apologising to Maisky for including in a recent speech some perfunctory mentions of Soviet maltreatment of civilians. He regretfully explained that his constituents would not yet accept unconditional support for the Soviet regime.98 Vansittart told Maisky in August 1937 that Britain approved of the pact the Czechs made with the Soviets in 1935.99 Had the pact been activated by war with Germany, the question of whether Soviet forces could have been evicted after being granted passage and bases was a grave concern for the Poles and Romanians at the time. When, in April 1939, Churchill asked Maisky on behalf of the Poles whether they need worry, Maisky avoided answering to avoid lying; Churchill was undeterred.100

War party

The Focus helped ensure that Chamberlain was assailed persistently from many angles. Irving mentioned that the initial secret fund was five times greater than the annual budget of the British Council, but in any case the Council was overseen by Reginald Leeper before Lord Lloyd became its chairman in July 1937; both men were supporters of the Focus.101 The Council began as a propaganda body under Leeper’s Foreign Office news department. Philip Taylor says that it was “created as a response to the malignant propaganda of the totalitarian regimes which had come into being following the Treaty of Versailles.”102 Taylor’s wording tidily excludes the most malignant “totalitarian regime” of all, but whatever the Council’s purview, Lloyd acted beyond it. John Charmley describes him as “an unofficial ambassador with the entrée to chancelleries from Paris to Ankara” and “a useful sounding-board whose words could, should it prove convenient, be denied.” He was intended as “an element of steel” in Chamberlain’s policy.103 However, Lloyd, like Churchill, had been of the Crowe school since long before the Great War, and demanded nothing but steel vis-a-vis Germany.104

Baldwin and Chamberlain allowed diplomatic sabotage to continue under them. Had they only been as merciless to warmongering subordinates as the latter demanded of them toward Germany, civilisation might still stand. Cohen, the Board of Deputies, the Foreign Office and the Soviet Embassy had already co-created a secret war party cutting across existing alignments and through departments of state. It was complacent of Chamberlain to merely remove Vansittart from his post in 1938 and narrow Leeper’s remit and not extirpate their practices. He inflicted a loss Lloyd and others could negate.

Chamberlain would have been remiss not to have Churchill surveilled, but he went no further.105 Churchill was free to conduct “his own foreign policy” and established “his own direct links with foreign governments… [H]e called upon foreign statesmen, sent out personal envoys… and encouraged the diplomatic corps to look upon Morpeth Mansions as a second Court of St. James.”106 His “own” foreign policy was that of Litvinov: aggravating Anglo-German relations to the greatest possible extent. “For us, there could be no peace with the Nazi regime,” as Spier said. Opportunities to subvert the peace arose in 1938 and the Focus became more a force than a presence.

Horus is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Churchill’s War, David Irving, 2003, p18, 23

Irving, p36

Irving, p37

According to David Irving, Churchill’s opponents “regarded the relentless assault on Ramsay MacDonald and his quest for disarmament as prompted by selfish political motives. But it was easy to contrast Macdonald’s tireless efforts with Hitler’s stealthy rearmament. It made good copy.” Irving, p37.

Irving, p23

Stalin’s War of Extermination, Joachim Hoffman, 2001, p30, 32

Daily Express, March 24th 1933, reproduced at https://www.nationalists.org/library/hitler/daily-express/judea-declares-war-on-germany.html. The Daily Express was the largest-circulation newspaper in the world at the time. Max Aitken (Lord Beaverbrook), the proprietor and an old friend of Churchill, became a minister in Churchill’s wartime government.

British Jewry and the Attempted Boycott of Nazi Germany, 1933–1939, Zbyněk Vydra, Theatrum historiae 21 (2017), p206

“Hitler’s Bitterest Foe”: Samuel Untermyer and the Boycott of Nazi Germany, 1933–1938, Richard Hawkins, American Jewish History, Volume 93, Number 1, March 2007, p31

Hawkins, p25, 26, 29, 30. Given Untermyer’s wild accusations, it is rational to wonder how often similar statements from others are uttered regardless of evidence.

Hawkins, p45. Irving says that “Citrine was angered by Hitler’s brutal closure of the trade unions.” Irving, p59. Stalin must have closed his unions less brutally.

See Labour and the Gulag – Russia and the Seduction of the British Left by Giles Udy, 2017. Much of the Labour Party, including Ramsey MacDonald, was pro-Soviet from 1917 to 1945. During the Cold War this became a fringe position in the party.

The Impact of Hitler, Maurice Cowling, 1975, p46

My Friend the Enemy : an English Boy in Nazi Germany, Paul Briscoe, 2008, p28. According to James Pool, Rothermere confirmed this to Mosley and Hitler. See Who Financed Hitler: The Secret Funding of Hitler’s Rise to Power, 1919-1933, James Pool, 1997, p315-6

Vydra, p206

Vydra, p200

Final Solution: The Fate of the Jews 1933–1949, David Cesarani, 2016, part one, section ‘Protest and Boycott’. Cesarani notes that the American Jewish Committee originally took the same position as Laski’s Board of Deputies while the American Jewish Congress sided with Untermyer and helped form the World Jewish Congress.

Hawkins, p49. Vilification was used in support of the boycott from the start.

Anglo-Jewish Responses to Nazi Germany 1933-39: The Anti-Nazi Boycott and the Board of Deputies of British Jews, Sharon Gewirtz, Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 26, Number 2, April 1991, p267

Vydra, p211

Vydra, p212

https://blog.nationalarchives.gov.uk/no-pasaran-battle-cable-street/ – note the approval of the authors. The Act was the creation of John Simon, who as Home Secretary had ultimate authority over all British police, including those wounded trying to uphold the law in Aldgate.

“Some lesser known aspects” – The Anti-Fascist Campaign of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, 1936-40, Daniel Tilles, p138

Tilles, p139

Vydra, p212

Tilles, p136. “Over 1937 the CoC established the London Area Council (LAC), a subsidiary body in the East End that took over the anti-fascist campaigning of the Association of Jewish Friendly Societies (AJFS), which had already been working in harmony with the Board.” Tilles, p143

Tilles, p140

Tilles, p151. Morrison and the Board of Deputies were already linked by their collaboration on the Anti-Nazi Council, of which Pinchas Horowitz was a member and Morrison was a vice-president. Irving, Churchill’s War, volume 1, chapter 6, note 4

Tilles, p140

Irving, p40

Irving, p40

The Defence Requirements Sub-Committee, British Strategic Foreign Policy, Neville Chamberlain and the Path to Appeasement, Keith Neilson, The English Historical Review, Volume 118, Number 477, June 2003, p662, 665

Neilson, p653

British Intelligence on the German Air Force and Aircraft Industry, 1933–1939, Wesley Wark, The Historical Journal, Volume 25, Issue 03, September 1982, p628

Wark, p630. The reasons for fixing Germany as the enemy are unmentioned; Wark simply calls it “obvious”.

Wark, p631

Irving, p48

Irving, p40-1. “There is no evidence to support the latter’s postwar claim that Morton did so with prime ministerial approval; other papers were just filched by Morton and never returned.”

Irving, p41-2. Simon, Hoare and Chamberlain were among those termed the Guilty Men in 1940 in a book published by the Jewish communist Victor Gollancz.

Twilight of Truth – Chamberlain, Appeasement and the Manipulation of the Press, Richard Cockett, 1989, p21

Cockett, p16-7

Cockett, p21

Cockett, p17-8

Cockett, p20

Cockett, p21

Cockett, p22

Wark, p629

Wark, p636

Cockett, p22

Churchill’s Man of Mystery – Desmond Morton and the World of Intelligence, Gill Bennett, 2007, chapter 9. Dansey was of some assistance to Leon Trotsky (born Lev Bronstein) in 1917 – https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2001/jul/05/humanities.highereducation

Irving, p81. Jurgen Kuczyinski later recruited Klaus Fuchs as a spy for the Soviet Union. Fuchs was handled by Jurgen’s sister Ursula (alias Ruth Werner) while he betrayed the British and American nuclear weapons research programmes.

Irving, p82. The origins of ‘bulldog and Spitfire’ nationalism become clearer.

Wark, p635

No More Champagne – Churchill and his Money, David Lough, 2015,ch18. Also see Irving, p52

Irving, p52

Irving, p111-2, 116, and Lough, notes for chapter 18

Lough, chapter 18

Lough, chapters 18, 20 and 21

Cockett, p24

Hawkins, p46. According to Irving, “The reason for the ANC approach to Churchill in April 1936 was this: in London, authoritative Jewish bodies including the powerful Board of Deputies had come out against the more strident boycott activities, lest these provoke the Nazis to more extreme measures; in New York, the firebrand Zionist leader Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, an associate of Untermeyer’s, disagreed and founded a militant World Jewish Congress based in Geneva. As the Board of Deputies was the principle source of its British finance, the A.N.C. shifted to a political approach in 1936, and began hiring helpers on the political scene.” Irving, p59

Focus – a Footnote to the History of the Thirties, Eugen Spier, 1963, p13. See also Irving, p67

Irving, p58

Irving, p58, 67

Spier, p99

Irving, P99-100

Irving, p170-1. Richard Weininger was brother of the famous Otto – see Robert Boothby – a Portrait of Churchill’s Ally, Robert Rhodes James, 1991, p198

Irving, p59-60

Irving, p100, 117. The Wittkowitz Mines and Iron Works “manufactured armourplate, partly for British navy contracts. The Austrian Rothschilds held a 53 per cent controlling share. In 1938 the well-informed Rothschilds transferred the company to the Alliance Assurance Company, a London Rothschild firm. Blackmailing the family to sell off their controlling interest to Germany, the Nazis imprisoned Louis Rothschild in Vienna. Even after they physically seized Vitkovice in March 1939, the haggling went on until the bargain was struck for £3.5Million. Irving, p118

Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler – The Diplomacy of Edvard Benes in the 1930s, Igor Lukes, 1996, p192-3

See Labour and the Gulag by Giles Udy, 2017

The Red Millionaire – A Political Biography of Willy Münzenberg, Moscow`s Secret Propaganda Tsar in the West, Sean McMeekin, 2003, p194. Angell wrote in the Daily Herald that ‘patriotism was a menace to civilisation’. See Cowling, p242-3. “Münzenberg had not forgotten the visceral appeal the antifascist campaign [in Germany in 1923] had had for celebrity intellectuals…” McMeekin, p194. “Thomas Mann did contribute a short article, as promised, in late November, and his piece was flanked by another impressive celebrity coup, an essay by Sigmund Freud on anti-Semitism.” McMeekin, p298

Red Millionaire, McMeekin, p296-7. Münzenberg, when expelled from the German Communist Party in 1936, denounced Stalin as a traitor to anti-fascism. Koestler previously used his job with the Focus-aligned News Chronicle as cover for his Comintern work.

“In so far as possible the engineering staff is kept 100% Hebrew, but Arabs are used for pick and shovel work.” The Seventh Dominion? – Time Magazine

Sir Robert Waley Cohen, 1877-1952: A Biography, Robert Henriques, 1966, p361. Cohen was a director of Royal Dutch Shell, a company created with Rothschild finance; New Court was the business premises of N M Rothschild. Natty Cohen, Robert’s father, was on the Russo-Jewish Committee. See Henriques, p42-3. In the tradition of the Anglo-Jewish Cousinhood, Cohen’s and his wife Alice were first cousins.

Henriques, p362-3. The Focus’s longer name was the Focus in Defence of Freedom and Peace. See also Hawkins, p46 and Spier, p9

Irving, p64. About the British Council’s budget, see Cultural Diplomacy and the British Council: 1934-1939, Philip Taylor, British Journal of International Studies, Volume 4, Number 3, October 1978, p244-265

Henriques, p363

Henriques, p363

Henriques, p364

Spier, p141

Henriques, p364

Spier, p108

Irving, p73

Lough, notes for chapter 11

Irving, p119

The Tribunite Who Tried to Kill Hitler, Marcus Bennett, 2021 – https://tribunemag.co.uk/2021/12/the-tribunite-who-tried-to-kill-hitler. Knop is the source for his own role. Meisel, also known as Hilda Monte, appears to have been part of a terrorist network: “Monte had given notice to Knop that on 18 July her group would conduct a ‘demonstration attack’ – on that day, nine people on the Nazi-chartered Strength Through Joy were killed in a boiler room explosion.”

Lough, chapter 18

Irving, p87. “Soon every major Hitler speech was countered by a well-paid Churchill riposte published in most of Europe’s capitals. – ‘The new encirclement of Germany!’ he quipped to the Standard’s editor.”

The Maisky Diaries: Red Ambassador to the Court of St James’s, 1932-1943, edited by Gabriel Gorodetsky, 2015, chapter on 1934

ibid.

Cowling, p156

Cowling, p157. Cowling is speaking of 1936, but Gorodetsky shows it was already the case by 1934 or earlier

Gorodetsky chapters on 1934 and 1940. Advocates of alliance with the Soviet Union find it expedient to call it ‘Russia’, falsely connoting continuity.

Gorodetsky, chapter on 1935

Gorodetsky, chapter on 1937

Gorodetsky, chapter on 1938

Irving, p121

Gorodetsky, chapter on 1937

Irving, p173

Lord Lloyd and the decline of the British Empire, John Charmley, 1987, p208, p211. See also Taylor

Taylor, p264

Charmley, p222

Charmley, p14

Irving, p100. See also Cockett p9

Irving, P99

A Népszava article glorifies the “heroic” Kun regime (July 18, 1919)

A Népszava article glorifies the “heroic” Kun regime (July 18, 1919) Péter Csunderlik (source: hirklikk.hu)

Péter Csunderlik (source: hirklikk.hu) Zoltán Bosnyák

Zoltán Bosnyák The sentencing and execution of József Papp by the Lenin Boys in Sátoraljaújhely (a city in the North-East of Hungary), April 22, 1919 (Hungarian National Museum)

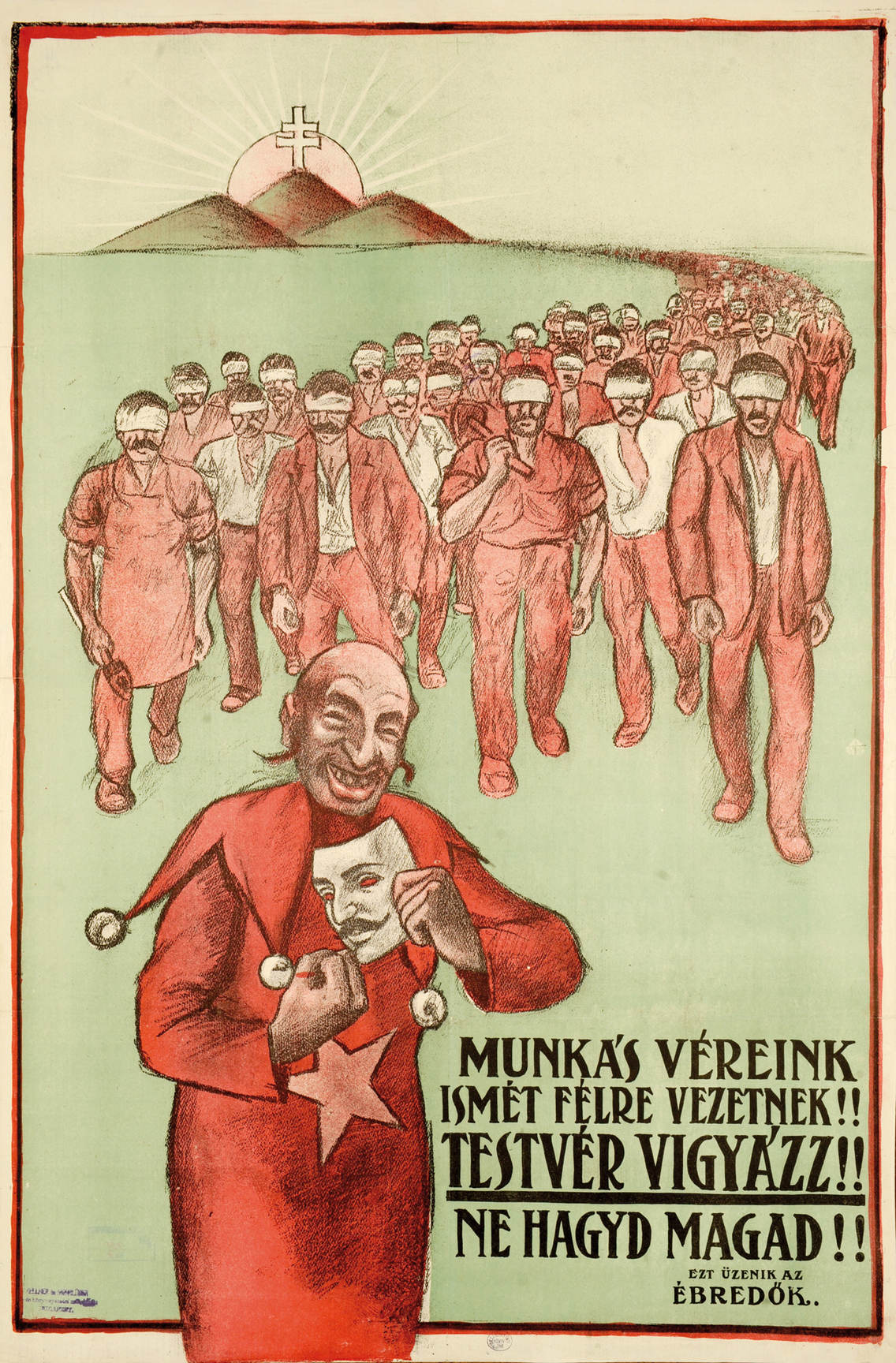

The sentencing and execution of József Papp by the Lenin Boys in Sátoraljaújhely (a city in the North-East of Hungary), April 22, 1919 (Hungarian National Museum) “Our worker brothers, you are being deceived again!! Watch out, brother!! Don’t let them!!”—poster of the Awakening Hungarians (Ébredő Magyarok) group warning after the fall of the Kun regime that Jewish influence did not disappear

“Our worker brothers, you are being deceived again!! Watch out, brother!! Don’t let them!!”—poster of the Awakening Hungarians (Ébredő Magyarok) group warning after the fall of the Kun regime that Jewish influence did not disappear Oszkár Jászi (source: szevi.hu)

Oszkár Jászi (source: szevi.hu) Some members of Po’alei Zion in Łowicz, 1917

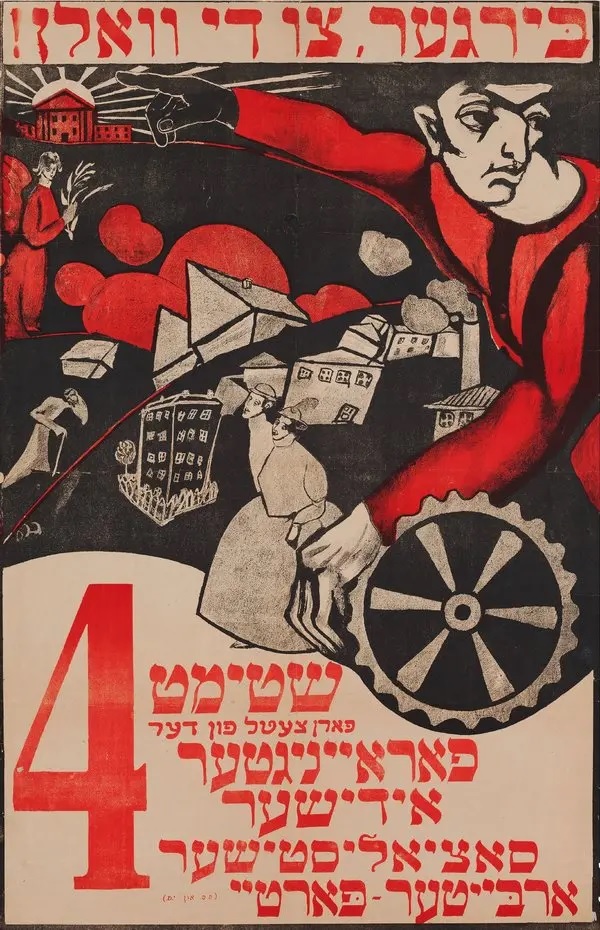

Some members of Po’alei Zion in Łowicz, 1917 “Vote for the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party” – Ukrainian election poster in Yiddish from 1917 (Ne Boltai Collection)

“Vote for the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party” – Ukrainian election poster in Yiddish from 1917 (Ne Boltai Collection)