Introduction

On the dissident right down-under, the intellectual, spiritual, and moral bankruptcy of mainstream Australian “conservatism” is a well-worn topic. Everyone expects conservatives to cuck when the question of White genocide or the great replacement is raised. Should attention shift away from racial politics to the relationship between politics and religion, however, most conservatives and radical rightists reveal a shared loyalty to a secular regime separating church and state.

This became evident to me while listening to a recent podcast discussion between Blair Cottrell (a photogenic, patriotic chad and working-class, “tradie,” activist from Melbourne) and Sydneysider Joel Davis (an on-line activist of a more educated and intellectual bent. [1] At first, both stuck to the usual script, agreeing that Anglo-Australian (or White) nationalism will never become a serious contender for state power in Australia so long as the Labor-Liberal duopoly retains its long-established stranglehold on mainstream party politics. But then, the conversation briefly strayed off the beaten path. Frankly clutching at straws, Cottrell wondered whether religion—Christianity, in particular—might offer an alternative medium for fruitful nationalist activism, outside and apart from the state. Davis immediately demurred, advising against mixing religion and politics. While avowing his personal faith in Catholicism as the “true religion,” he worried that making race a religious issue (or vice versa) would undermine the already fragile unity of the embryonic nationalist movement among White Australians.

In a supposedly secular society such as contemporary Australia, such a view passes as the conventional wisdom. Significantly, what goes unmentioned here is the relationship between ethnicity, specifically Anglo-Australian, or White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) ethnicity, in its relationship to both state and church. This is especially remarkable in Australia where WASPs are still a (shrinking) majority of the population. How, then, did religion become separated from Anglo-Australian ethnonationalism? Indeed, how was Anglo-Australian ethnicity itself relegated to the margins of political discourse on the dissident right? Why should an Anglo-Protestant ethnic majority adopt instead a generic “White” or “European” racial identity? Why should they forswear their collective birthright to an ancestral stock of social, cultural, and spiritual capital—the common blood, language, and religion—generated in the course of a unique history played out on a global stage?

After all, not so very long ago, Irish Catholics in Australia and elsewhere routinely employed the church in pursuit of their ethnic interests, in opposition, if need be, to their Anglo-Protestant “fellow Whites.” Interestingly, the secularization of politics in Ireland has coincided with the accelerating demographic displacement of the Irish people. Apart from the Irish, do Jews not mix religion and politics? Who can deny that Judaism is an ethnoreligion with a distinctive political theology of its own grounded, nowadays, in the Holocaust mythos? Significantly, in Canada, “Holocaust denial” is now a crime under a newly enacted blasphemy law which came hot on the heels of the 2018 repeal of blasphemy laws originally intended to protect the Christian religion.[2] In the rest of the Anglosphere, social conventions alone still enforce public respect for Jewish political theology by governments, the corporate sector, and society at large. Moreover, synagogues have long been a significant vehicle for Jewish ethnopolitical action. What prevents Anglo-Protestants from viewing “their” churches in a similar light?

It is not that either Catholic or Anglo-Protestant churches seek to build a wall between religion and politics (understood as who gets what, when, where, and how). Rather, they refuse to mix religion with ethnicity (much less race). Or to be more precise, while countenancing ethnic congregations for non-White minorities, churches expect Anglo-Protestant parishioners to maintain a strict separation between their “ethnicity” and their “religion.” Christian clerics, across denominations, turn a blind eye to the enchanted world of Greco-Roman antiquity, where religion, as such, did not actually exist. In fact, in the Roman empire of the first century, not even Jesus (or his apostle Paul) distinguished religion from ethnicity.

For Jews, no less than Samaritans, Greeks, and Romans, one’s identity, fate, and destiny derived from kinship with the gods of one’s family, tribe, and city. “What modern people think of as ‘religion,’ ancient people articulated and experienced as family inheritance, [and] ‘ancestral custom.’” In such a world, “ethnic distinctiveness and religious distinctiveness are simple synonyms, and native to all ancient peoples.” Moreover, Paula Fredriksen adds, “ancient peoples, Jews included, did not ‘believe’ or ‘believe in’ their ancestral customs. They enacted them; they preserved them; they respected them; they trusted or trusted in them.” In pre-Christian antiquity, the two key populations were gods and humans. Ancient societies “could thrive only if gods were happy. Cult was the index of human loyalty, affection, and respect.” Just as “cult was an ethnic designation,” so too “ethnicity was a cult designation.” In other words, “gods ran in the blood. Peoples and their pantheons shared a family connection.” [3]

Accordingly, it was only because Jesus of Nazareth was acknowledged as the Son of Israel’s God that he could expect to be exalted as King of the Jews. Indeed, he declares explicitly that he “was not sent except to the lost sheep of the house of Israel” (Matt. 15:24). How then can Anglo-Protestants, or even Anglo-Catholics, deny the religious roots of their racial kinfolk both “at home” and “abroad” in the Anglo-Saxon diaspora? The contemporary Anglo-Protestant diaspora resembles the dispersion of Hellenistic Jews among whom the apostle Paul worked during his mission to the God-fearing pagans of the Roman Empire. Indeed, Paul sought to reconnect with those “lost Israelite sheep” during that mission. As we will see, Jesus and Paul shared an ethno-theology in which the history of Israel according to the flesh was the medium through which the spiritual destiny of the Israel of God was to be fulfilled.

What prevents churches throughout the Anglosphere from developing an ethno-theology enabling White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) to recover a shared ethnoreligious spirit of meaning, value, and purpose? I believe that Blair Cottrell had some such intuition at the back of his mind during his discussion with Joel Davis. Joel, by contrast, confines (dare I say, dooms) the Anglo-Australian nationalist movement to a secular, explicitly “one-dimensional” strategy of racial politics. Looking back on the Jesus movement of the first century, however, I am convinced that the regeneration of deracinated, spiritually anemic Anglo-Australians will require a multi-pronged and transnational, three-dimensional movement. The goal must be to reinvigorate the historic bonds of religion, race, and ethnicity within and between the peoples of the British diaspora. Nothing less than a broad spectrum, deep-seated renaissance of British race patriotism will overcome the soul-destroying, nihilistic materialism of globalist plutocracy. Any such Great Awakening in our time requires a religious reformation reconnecting Anglican (and other Anglo-Protestant) churches to their ancestral roots in the Angelcynn church fostered by Alfred the Great (849–899).

The Problem with Christian Nationalism

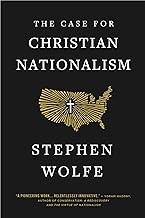

Why then, have I criticized the American-style Christian nationalism championed by Stephen Wolfe?[4] Certainly, in many respects, we are on the same side. Not only is Wolfe opposed to the globalist regime  headquartered in Washington D.C. and New York, but he is also critical of the evangelical Protestant establishment. Before publication of his best-selling book on Christian nationalism, Wolfe had already written a series of online articles deploring “the sorry state of evangelical rhetoric.”[5] There he charged that American evangelicals have become addicted to the use of shopworn rhetorical devices designed to capture the moral high ground from their critics without ever having to take them seriously. Most obviously, virtue-signalling Christians routinely remind those advocating an end to mass Third World immigration that we must “love our neighbours.” Wolfe rightly complains that serious moral and political discourse, is impossible so long as such rhetorical devices are automatically invoked to short-circuit debates with anyone who could lead evangelicals down the path to ethnonationalism.

headquartered in Washington D.C. and New York, but he is also critical of the evangelical Protestant establishment. Before publication of his best-selling book on Christian nationalism, Wolfe had already written a series of online articles deploring “the sorry state of evangelical rhetoric.”[5] There he charged that American evangelicals have become addicted to the use of shopworn rhetorical devices designed to capture the moral high ground from their critics without ever having to take them seriously. Most obviously, virtue-signalling Christians routinely remind those advocating an end to mass Third World immigration that we must “love our neighbours.” Wolfe rightly complains that serious moral and political discourse, is impossible so long as such rhetorical devices are automatically invoked to short-circuit debates with anyone who could lead evangelicals down the path to ethnonationalism.

Wolfe presents a persuasive critique of “christianizing rhetorical devices.” He refers there to the evangelical habit of grounding arguments in what they take to be “an undeniable Christian truism” (e.g., “all of us are made in the image of God”). This rhetorical tactic forces opponents “to contend with an undeniable statement offered for a predetermined moral conclusion.”[6] For my own part, I first began to push back against the unreflective moral certitude of Anglo-Protestant discourse when, as a bookish teen-ager in small-town Ontario, I discovered the English philosopher Bertrand Russell.

A callow youth with an embryonic goatee, I relished my new-found vocation as the village atheist. I was amazed by the ease with which I could confound church-going classmates with talking points I lifted from Russell’s treasure trove of skeptical essays.[7] Still, I was no more a militant atheist than Russell himself, being much more taken by his skeptical agnosticism. After high school, as I studied history through to an honours degree and graduate school, I simply lost interest in the milk-and-water sermonizing style of Anglo-Protestantism, Canadian-style.[8]

Not until my late twenties was my childhood Sunday School receptivity to Christianity fortuitously rekindled. Having, at long last, graduated from law school in Canada in the mid-seventies, I seized the opportunity to avoid the grind of legal practice by teaching law in Australia. Fortunately, I soon landed a job in a new law school in Sydney where I developed and convened a first-year foundation course on the history and philosophy of law. That course was based on the premise that the common law tradition grew out of a Greco-Roman civilization reshaped by the triumph of Christianity. So, while remaining an unchurched agnostic, I gradually absorbed the sort of cultural Christianity now stoutly defended by Stephen Wolfe.

Not long afterwards, while working on a master’s degree at Harvard Law School, I discovered the fascinating interplay between Anglo-American Protestantism and the classical republican traditions shaping the federal constitution of what seemed, by comparison with European absolutism, the almost stateless character of American civil society. Although it has attracted accusations of authoritarian statism, Wolfe’s Christian nationalism owes a lot to the Anglo-Protestant evangelical tradition of anti-institutional populism. Long story short: American constitutional history has been shaped by the political theology of evangelical Protestantism which exalted the double majesty of the Divine Economy and good King Demos. Over the years, I have written good deal on that subject.[9] Decades later, after leaving legal education behind (let us say, involuntarily) I began to wonder, as Blair Cottrell did above, whether Christianity, particularly the Anglican church, could ever develop an effective response to the spiritual, moral, and intellectual crisis of WASP managerial, professional, and political elites. I persuaded myself that I should at least get some skin in the game by getting baptized in a local Anglican church. Having lamented the collapse of English Canadian nationalism as a young man, I am now deeply disturbed by the disastrous decline of WASP hegemony everywhere in the Anglosphere.[10] Embarking on a search for the spiritual roots of that crisis, I decided to earn a degree in theology.

I therefore possess personal, political, and professional interests in the prospects for an ethnoreligious solution to the existential crisis now facing the Anglo-Saxon peoples. Unfortunately, Wolfe rests his own case for Christian nationalism upon an a priori faith in a pair of “undeniable Christian truisms.” Hoping to establish the legitimacy of a Christian nation ruled by a Christian prince, he simply asserts the truth value of two “mixed syllogisms” which combine natural law with certain “supernatural truths,” or theological presuppositions revealed by grace. He claims, for example, that the catchphrase “Jesus is Lord” is a “universally true statement.” Likewise, the proposition that “Christianity is the true religion,” grounded as it is in revelation rather than reason, requires no argument.[11] But surely, even if one accepts the presupposition that those statements are “true,” one is entitled to ask: “In what sense are they true?” What if the most that can expect to find in such “undeniable Christian truisms” is some sort of “truthiness”[12]?

Wolfe’s political theory of Christian nationalism aims to secure the Lordship of Jesus by resurrecting blasphemy and Sabbatarian laws designed to drive atheism and heresy from the public sphere. In principle, this political program knows no borders. If Christianity is the true religion, it must be “a universal religion—a religion for all nations.” But, Wolfe concedes, “it does not eliminate nations.” Rather, Christianity completes, indeed, it perfects nations as well as individual recipients of divine grace.[13] A non-Christian nation (or person) is, therefore, an imperfect nation (or person).

So long as America retained its identity as a Christian nation, Wolfe contends, it was entitled to defend itself against advocates of atheism and immorality. And so, it did. For example, even in secular and cosmopolitan New York City and, as late as 1940, concerned citizens successfully campaigned to prevent Bertrand Russell from taking up a teaching position at the City College in the fields of logic, mathematical theory, and the philosophy of science. The justification for this violation of academic freedom: As the author of notorious (but, to many, high-minded, measured, and persuasive) essays such as those collected in my broken-backed copy of Why I Am Not a Christian, Russell was allegedly an unrepentant advocate of atheism, public nudity, and free love.[14] Clearly, at that time, American Anglo-Protestants had few qualms about using state power to enforce creedal conformity. The churches then were still a force to be reckoned with and Wolfe clearly hankers after those days.

But that was then; this is now. In the past fifty years or so, Protestant churches and their denominational theological colleges have offered little resistance, and more than a little support and encouragement to the rise of Woke America. Wolfe, of course, recognizes that the ascension of an evangelical “Christian Prince” to state power is unlikely to occur anytime soon. Nor does he expect “really existing,” mainstream Protestant churches to enter the political arena themselves, fighting to reverse the browning of America, overturn the gynocracy, or dismantle the Global American Empire (GAE). At most, churches might be third-party beneficiaries of a lay, pan-Protestant, nationalist movement combatting demonic powers and principalities on their behalf. A more counter-intuitive threat to Globohomo is hard to imagine.

Nevertheless, Wolfe has become a prominent figure on social media, regularly sniping at an evangelical establishment on board with the globalist agenda of the transnational corporate welfare state. In his view, the globalist regime threatens both his religion and his nation. As a Reformed Presbyterian political theorist, however, Wolfe rides two unruly horses—ethnicity and religion—simultaneously. Only by keeping both his ethnic identity and his religious faith on a steady diet of blood thinners can he keep his seat. But any Christian nationalism worthy of the name must recognize, sooner or later, that strong gods demand the unapologetic fusion of race, ethnicity, and religion.

Religion and Ethnicity: Then and Now

On Wolfe’s political theory, ethnicity is, by nature, a particularistic phenomenon situated within earthly kingdoms governed by civil magistrates, the realm Augustine of Hippo described as the City of Man. Reformed theology and Protestant churches, on the other hand, are oriented by grace towards a heavenly kingdom, the eternal City of God, where the Lord Jesus reigns, sitting at the right hand of the Father. Civil magistrates must accommodate the ethnic identities, needs, and interests of his subjects, but the triune God of Reformed theology is colour-blind. Many New Testament scholars now contend, however, that this presupposition contradicts an undeniable historical truism fundamental to the cosmology shared even by Jesus of Nazareth and Paul, his apostle to the Gentiles. In the enchanted realm of Greco-Roman antiquity, religion and ethnicity were indistinguishable; they were literally syngeneic, originally a Greek word signifying both kinship and citizenship.

In those days, every member of the same genos shared a family connection extending “not only horizontally, between citizens of the Hellenistic polis; it also extended vertically between heaven and earth.” In short, Greco-Roman cities “were not secular spaces. They were family-run religious institutions.”[15] That enchanted world was saturated with gods; every forest and river, every family, tribe, and city had its own gods who must not be offended lest they visited retribution on those subject to their supernatural powers. For Jews, Greeks, and Romans, one’s religion was not about beliefs, creeds, and confessions of faith. In the world we have lost, religion was synonymous with the ritual rites and obligations prescribed by one’s mythological ethnic identity and ancestral allegiances.[16]

Wolfe, however, is loath to ground Christian nations in a syngeneic fusion of religion and ethnicity. Instead, he thinks of ethnicity as the “phenomenological topography” of a “people in place.” Rather grudgingly, Wolfe acknowledges that ethnicity may run in the blood.[17] But Christian identity, he believes, transcends primitive notions of kinship with the ancestral gods of family, tribe, or nation. Like Wolfe, Anglo-Protestants generally remain stubbornly resistant to the notion that spirit is fused together with blood, indissolubly, in holy communion with the water of life (1 John 5:8).

At the same time, Wolfe’s Christian political theory remains resolutely old-fashioned in its respect for ecclesiastical authority. Anglo-Protestantism may be a bloodless religion, but it still adheres to ancestral creeds formulated in late antiquity by the Church Fathers. Notably, in preparation for his book, Wolfe immersed himself in the works of seventeenth-century Reformed theologians largely unknown to more than a few of his fellow Anglo-Protestants. Even more anachronistic is his reliance upon the Thomist tradition of natural law dating back to the Middle Ages. Biblical exegesis, on the other hand, is conspicuously absent from his work. Like most Anglo-Protestants, he is content to leave that task to the pastors and theologians who stand behind the Westminster Confession of Faith. Nor has he engaged with the growing body of contemporary New Testament scholarship ready, willing, and able to challenge the foundational “supernatural truths” of Wolfe’s old-time religion.

Wolfe’s brand of Christian nationalism will need more than recycled theological truisms dredged up from dusty Calvinist tracts to gain traction outside the echo chambers of pious evangelicalism. Mindlessly repeating that “Jesus is Lord” carries little weight outside that charmed circle. Similarly, after four centuries of experience with Anglo-Protestantism, it will be a hard sell to persuade Moslems, Jews, and nihilistic atheists, much less millions of marginalized White men, that “Christianity is the true religion” destined to “perfect” the already perfectly fictional “American nation.” As Wolfe recognizes himself, the conventional attachment to a non-creedal, unchurched, cultural Christianity reaches its vanishing point when one’s nation turns into a gay disco.

Indeed, already in 1940, it was evident that Bertrand Russell was far from being a lone skeptic in opposition to the merely voluntary Protestant establishment. At home, religious diversity was an established fact: Catholics, Jews, and Mormons had secure beachheads in America. Abroad, the country would soon join godless Soviet communists in its war on Germany. Hardly surprisingly then that, within a few decades after the war, the USA was to be utterly transformed by a civil rights revolution and its corollary, mass Third World immigration. Mainline Protestant churches put up only token resistance before they obediently fell in line with the entire progressive agenda.

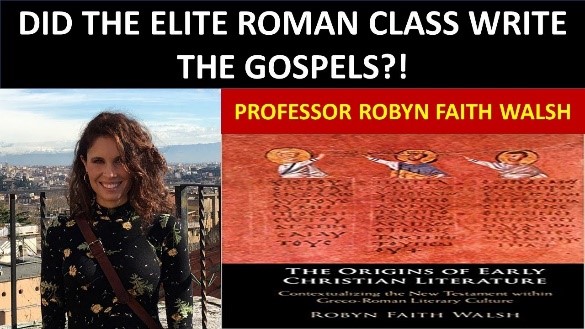

Nowadays, secular humanists, rationalist skeptics, mythicists, historicists, and atheists aplenty have found influential platforms in the religious studies departments of major American universities. Offering challenging new perspectives on once undeniable Christian truisms, they present a solid prima facie case for free thought in religious matters. Their claim that the “supernatural truths” asserted by Christian churches rest less on reason and revelation than on myth and fable cannot easily be swept under the carpet.

Pushed beyond the pale by both evangelical theological seminaries and mainstream Protestant churches, independent preterist scholars and dissident churches question the creedal promise that, some time in our future, the Lord Jesus “will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead.” Conservative evangelicals insist that Jesus will return physically (“as a 5̍ 5̎ Jewish man,” in Don K. Preston’s wry phrase) riding on clouds of glory, at the end of the Christian age, to usher in a new heaven and a new earth. By contrast, preterists employ a Hebrew hermeneutic in defending their persuasively biblical covenantal eschatology. They hold that the Parousia (i.e., the Second Coming of Jesus Christ), occurred, as prophesied in the Old and New Testaments, with the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in AD 70. Hence, many New Testament scholars, skeptics and preterists alike, can agree that, for those of us in the present, the futurist eschatological hope, as preached in the creedal churches (though differing as to its pre-millennial, post-millennial, or amillennial timing) is little more than a chimera.

Do bible-believing preterists and skeptical scholars deserve a respectful hearing from creedal Christian nationalists? In principle, Stephen Wolfe approves the restoration of Sabbatarian and blasphemy laws to exclude political atheism and public heresy “from acceptable opinion and action.”[18] Wolfe publicly affirms creedal orthodoxy on eschatology; he “looks to the future coming of Christ (Tit. 2:13)” and hopes “for the glorification of the body promised to us in Christ (Phil. 3:21).”[19] One cannot but wonder whether he would vote to convict preterists such as Don K. Preston were he to sit on a jury in a prosecution for public heresy.

Don K. Preston

Wolfe certainly believes that “public heresy has the potential to harm other’s souls by causing doubt or distraction or by disrupting public peace.” According to his Christian political theory, therefore, the civil “magistrate, who must care for the souls of his people, may act to suppress that heresy.” Note as well that Wolfe agrees in principle with Francis Turretin, his favourite seventeenth-century theologian, that arch-heretics “publicly persistent in their damnable error … can be justly put to death.”[20] Having endorsed Don K. Preston’s views on fulfilled eschatology, repeatedly and in public, I fear that a “Christian prince” would convict me of arch-heresy. I can only hope that he might find it imprudent to condemn me to death.

Anglo-Protestant “nationalists” proposing to outlaw atheism and heresy could ease the minds of those who might be accused of public atheism by explaining just how the historical Jesus became the eternal Lord of the Anglo-Saxon, British-descended peoples. WASP agnostics will ask why only a bloodlessly cosmic “Christianity” can be their “true religion.” Looking further afield for potential defendants, Wolfe’s pan-Protestant program to enshrine the “supernatural truths” of creedal Christianity into public and criminal law is sure to generate powerful pushback from a multitude of other groups. Massive resistance will come, not just from mild-mannered academics and pious preterists, but from marginalized Muslims, deeply entrenched Jewish elites, miscellaneous unbelievers, and moral degenerates, not to mention businesses, large and small, which profit from the abolition of Sunday blue laws and the concomitant licencing of atheistic, materialist nihilism seven days a week.

Note as well that the heretical theological voices discussed below have found mass audiences on, inter alia, YouTube channels such as MythVision Podcast.[21] Many Christian nationalists such as Stephen Wolfe (as well as White nationalists who happen to be Christian, such as Joel Davis in Australia) are themselves adept in the use of social media. But, wedded as they are to the “supernatural truths” enshrined in traditional church creeds, they are certain to be pushed onto the political and intellectual defensive. Indeed, as we have seen, Davis prudently prefers not to mix his Catholic religion with his ethnopolitics. And for good reason, since what churchgoers take to be the most self-evident of theological truisms—the notion that Jesus and the apostle Paul were Christians—is now up for debate. Certainly, among contemporary New Testament scholars, no consensus supports the proposition that Jesus was sent or that Paul was called to found a new religion, especially one cleansed of his own ethnic identity.

Jews, Judaism, and the Idea of Israel in the First Century AD

My argument is an ethno-theological interpretation of the origins and outcome of the Jesus movement in the first-century world of Greco-Roman antiquity. In a nutshell, Jesus and Paul inspired a dissident ethnoreligious movement “within Judaism”; neither presented himself as the Founder of Christianity. The movement first emerged in Judea after the death and reported resurrection of Jesus. By the time Jerusalem was destroyed by Roman armies in AD 70, the gospel had been carried to the ends of the known world through the social networks and synagogues established within the far-flung diaspora of Hellenistic Jews.

Not all Jews, either in Judea or in the diaspora were supporters of the Jesus movement. The Jesus movement was at odds with ethnonationalist Judeans involved in a long-simmering rebellion against Rome, leading to the Jewish wars in 66AD. Those Judean nationalists followed in the footsteps of the Maccabean rebellion against Hellenistic influence in the second century B.C. During his ministry, Jesus also came into conflict with the leaders of the Temple cult centred on Jerusalem. The Jesus movement stood for an ethno-theology with two central features. First, its aims were explicitly geopolitical in scope, extending beyond Judea to the entire known world (oikumene); and, secondly, the movement was driven by the sense of urgency inherent in its apocalyptic eschatology. Both Jesus and Paul taught that the “end of the age” was nigh. They and their followers looked forward to the long-promised but now imminent restoration of “all Israel” in a new heaven and new earth.

The suggestion made in the previous paragraph that the Jesus movement developed “within Judaism” is a deceptively simple claim. To the modern mind, the term “Judaism” connotes a “religion” which itself is misleading. Moderns associate “religion” with a set of doctrines pertaining to the nature of the divine or supernatural realm. Even the term “Judean” is anachronistic when used to signify an “ethnicity” as distinct from the modern category of “religion” supposedly implicit in the word “Jew.” But, as we have already seen, the very attempt to distinguish religion and ethnicity in the ancient world is itself anachronistic.[22] In particular, it makes no sense to distinguish the ethnic and religious aspects of Jewishness in this period. In translations of ancient texts, however, the English word ‘Judaism’ is often supplied in place of phrases literally denoting “the ancestral traditions, laws, and customs of the Jews.” This suggests that the “various elements that constitute our religion” were “inextricably bound up with other aspects of their life.” In the Greco-Roman world, generally, there were “a variety of modes in which people could think about and interact with the divine world,” including ritual and myth. These aspect of ancient life “overlapped and interacted in various ways” without forming the sort of “integrated system” or “unified understanding of the divine” that we call “religion.”[23]

Certainly, there were no ancient Hebrew or Aramaic words which correspond to our ‘Judaism’. There were Greek and Latin words that appear to do so (namely, Ίουδαϊσμός and Iudaismus) but, before the period 200–500 AD, they are used only a very few times, in Greek, most during the Maccabean period of the second century, BC. The very restricted usage of that Greek word for Judaism usually occurs “in explicit or implicit contrast with some other potential affiliation, movement, or inclination.” This brings us to Hellenism and its cognate verb, Hellenize. The basic meaning of Hellenize was “to express oneself in Greek,” occurring “chiefly in contexts where there are doubts about the speaker’s ability because he is a foreigner or uneducated.”[24]

Significantly, the first attestation of the word Hellenism is in the same second-century BC text that hosts the first occurrences of the word ‘Judaism’. The latter word “appears to have been coined in reaction to cultural ‘Έλληνισμός’ (Hellenism). In that context, ‘Judaism’ signified “a certain kind of activity over against a pull in another, foreign direction,” specifically Hellenism which “introduced foreign ways—Greek cultural institutions, education, sports, and dress—into Jerusalem.” It therefore refers to “a defection that threatens the heart and soul of Judean tradition.” The Maccabean revolt “was a counter-movement, a bringing back of those who had gone over to foreign ways: a “Judaizing” or Judaization, which the author of 2 Maccabees programmatically labels Ίουδαϊσμός (Judaism).[25]

The term ‘Judaism’, therefore, has a double meaning corresponding to the difference between what anthropologists call an etic meaning, derived from an external or observer’s point of view and the emic or insider’s view that a first-century Jew would have as a participant in his own collective way of life. From that emic point of view, it makes no sense to distinguish between ethnicity and religion.[26] A further source of confusion over terms such as ‘Jew’ and ‘Jewishness’ has to do with the difference between modern and ancient understandings of the relationship between Jews, Judeans and the idea of Israel. Jason Staples points out that moderns usually presume that, after the Babylonian Exile, the term ‘Israel’ is synonymous with ethnic Jews.[27] In fact, historically speaking, “Israel is an entity larger than (but including) the body of ethnic Jews.” Here, ‘Jews’ or ‘Judeans’ “refers to persons descended from the southern kingdom of Judah [whether they live outside Judea or not], which is only a part of the larger historical entity called Israel.” By contrast, “Israel” is a polyvalent term with at least four distinct references in the Hebrew Bible: (1) the patriarch Jacob/Israel; (2) “the nation composed of his descendants, that is, all twelve tribes of ‘Israel,’ including Judah”; (3) the northern kingdom, the ten tribes of the “house of Israel,” excluding the southern kingdom, the “house of Judah”; and (4) the returnees from Judah after the Babylonian Exile.[28] The Ioudaioi (Judeans) were the only Israelites who returned from Babylon. According to the late first-century Jewish historian, Josephus, the other ten tribes were scattered “beyond Euphrates till now and are a boundless multitude, not to be estimated by numbers.”[29]

Keep in mind that the Hebrew Bible came into being after the disappearance of those ten lost tribes. This fact is crucial to an understanding of the Jesus movement in the first century. Staples emphasizes that “the Hebrew Bible is scripture collected and edited by Jews, for Jews, about Israel.” He observes that “interpreters have been too quick to assume that the (actual) Jewish audience of these texts is the same as the Israel to which the texts are rhetorically addressed.” Instead, most of Israel existed only in the historical imagination after the Babylonian Exile. Accordingly, “through the collection and redaction of the prophetic literature and authoritative historical narratives that ultimately comprised the Hebrew Bible, exilic and post-exilic Jews established a continual reminder of the broken circumstances of the present, constructing an Israel not realized in the present.” These early Jews, in other words, located “themselves in a liminal space between the memory of a past ‘biblical’ Israel and the hope for a future restored Israel.” They created a “restoration eschatology” which looked forward, not to “the end of the world, but rather the end of the present age and the dawn of a new one.” In that new creation “all Israel” was to be restored by the in-gathering of all twelve tribes of the Dispersion into Zion.[30] The Lordship of Jesus the Christ was closely associated with the longed-for restoration of “all Israel.”

Although the ten lost tribes remained but a ghostly presence during the first century, a highly visible Jewish diaspora had been a well-established historical presence in major centres of the Greco-Roman world for hundreds of years. In fact, the Hellenized Jews of the diaspora greatly outnumbered those living in Judea. Rodney Stark estimates that while there were about one million Jews in Palestine, there were somewhere between four and six million to be found in wealthy and populous urban communities throughout the Roman empire. Indeed, “Jews had adjusted to life in the diaspora in ways that made them very marginal vis-à-vis the Judaism of Jerusalem.” The result was that the Hebrew language skills of most Hellenized Jews “had decayed to the point that the Torah had to be translated into Greek.” The Septuagint itself, therefore, became another medium through which Hellenistic perspectives found expression. Jews of the diaspora were Hellenized to the point that they needed the sort of cultural compromise allowing a Jew to remain a Jew while claiming full entry into “the elect society of the Greeks.” As for the other side of the ethno-cultural divide, many so-called God-Fearers, or Gentile “fellow-travellers,” were attracted to Hellenized Jewish traditions and customs, especially their moral teachings and monotheism, without being willing to “take the final step of fulfilling the Law” by giving up their own cultic gods and undergoing circumcision.[31]

Stark suggests that, when Jewish authorities decided not to require god-fearing Gentiles to observe the Law in full, they went some way towards the creation of a “religion” free of ethnicity.[32] This claim is seriously misleading. Paula Fredriksen observes that it was “a normal aspect of ancient Mediterranean life” to show respect for gods not one’s own, for Jews no less than pagans. To forge “an exclusive commitment to a foreign god, however—an act unique to Judaism in the pre-Christian era—was tantamount to changing ethnicity” and, hence, would have been perceived as an act of disrespect to the gods of the host city. At the same time, however, majority cultures were “religiously commodious.” Interested Gentiles “were free to frequent Jewish gatherings,” assuming “whatever Jewish practices, traditions, and customs they wished, while continuing unimpeded in their own cults as well.”[33]

The Jesus movement therefore found receptive audiences throughout the Hellenized Jewish diaspora among both Jews and Gentiles. Even so, Stark contends, the movement “offered twice as much cultural continuity to the Hellenized Jews as to Gentiles.”[34] On this point, Stark’s interpretation gains added force if one takes the view, contra Stark, that the first century Jesus movement developed “within Judaism” and, hence, pre-dated the “parting of the ways” which marked the historical beginning of Christianity proper in the second century.[35] Given “the marginality of the Hellenized Jews, torn between two cultures,” the Jesus movement “offered to retain much of the religious content of both cultures and to resolve the contradictions between them.” Not only were diasporan Jews “accustomed to receiving teachers from Jerusalem,” but movement missionaries (such as Paul) “were likely to have family and friendship connections with at least some of the diasporan communities.” The Jesus movement, in short, built a distinctly Hellenized religion on Jewish foundations, injecting “an exceedingly vigorous other-worldly faith” into the abstract universalism of Platonic philosophy.[36] It was in that cross-cultural context that Jesus became God.

Go to Part 2.

[1] The Joel & Blair Show https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y1ZRketjuIY&t=3532s

[2] Andrew Fraser, “Friend or Foe? The Holocaust Mythos, Global Jesus, and the Existential Crisis of Anglican Political Theology,” (2022) Vol. 22(3) The Occidental Quarterly 63.

[3] Paula Fredriksen, “Divinity, Ethnicity, Identity: ‘Religion’ as a Political Category in Christian Antiquity,” in Armin Lange, et.al., Comprehending Antisemitism through the Ages: A Historical Perspective (Open Access: De Gruyter, 2021), 101-120, at 102-103; idem, “Judaizing the Nations: The Ritual Demands of Paul’s Gospel,” 56 New Testament Studies 232, at 234-235.

[4] Andrew Fraser, “Sweet Dreams of Christian Nationalism (But What About the Protestant Deformation, Globalist Churches, and Jewish Political Theology?),” 2023(2) The Occidental Quarterly 37.

[5] Stephen Wolfe, The Case for Christian Nationalism (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2022); idem, “The Sorry State of Evangelical Rhetoric,” http://sovereignnations.com/2018/06/22/sorry-state-evangelical-rhetoric/

[6] Ibid.

[7] Bertrand Russell, Sceptical Essays (London: Unwin Books, 1960).

[8] Pierre Berton The Comfortable Pew: A Critical Look at Christianity and the Religious Establishment in the New Age (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1965).

[9] See, Andrew Fraser, The Spirit of the Laws: Republicanism and the Unfinished Project of Modernity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990), esp. 31-40, 129, 216; The WASP Question: An Essay on the Biocultural Evolution, Present Predicament, and Future Prospects of the Invisible Race (London: Arktos, 2011), 241; and Reinventing Aristocracy in the Age of Woke Capital: How Honourable WASP Elites Could Rescue Our Civilisation from Bad Governance by Irresponsible Corporate Plutocrats (London: Arktos, 2022) 16.

[10] Cf. George Grant, Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism (Ottawa: Carleton University Press, 1988 [orig. ed. 1965).

[11] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 120, 183.

[12] Defined by the Merriam-Webster Dictionary as: a truthful or seemingly truthful quality that is claimed for something not because of supporting facts or evidence but because of a feeling that it is true or a desire for it to be true.

[13] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 26.

[14] Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian, Edited with an Appendix on the “Bertrand Russell Case” by Paul Edwards (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1957).

[15] Paula Fredriksen, “How Jewish is God? Divine Ethnicity in Paul’s Theology,” (2018) 137(1) Journal of Biblical Literature 193, at 194-195.

[16] Fredriksen, “Divinity, Ethnicity, Identity,” 106.

[17] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 134-137.

[18] Ibid., 384-387.

[19] Stephen Wolfe, “The Church Among Nations,” August 1, 2023, American Reformer http://americanreformer.org/2023/08/the-church-among-the-nations/

[20] Wolfe, Christian Nationalism, 387-388, 391.

[21] https://www.youtube.com/@MythVisionPodcast

[22] See also, Jason A. Staples, The Idea of Israel in Second Temple Judaism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 17-18.

[23] Steve Mason, “Jews, Judeans, Judaizing, Judaism: Problems of Categorization in Ancient History,” (2007) 38 Journal for the Study of Judaism 457, at 480, 482.

[24] Ibid., 463-464.

[25] Ibid., 464-467.

[26] Ibid., 458-460.

[27] Staples, Idea of Israel, 25.

[28] Jason A. Staples, “What Do the Gentiles Have to Do with ‘All Israel’? A Fresh Look at Romans 11:25-27,” (2011) 130(2) Journal of Biblical Literature 371, at 373-375.

[29] Quoted in Staples, Idea of Israel, 49.

[30] Ibid., 89, 94-95.

[31] Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity: How the Obscure, Marginal Jesus Movement Became the Dominant Religious Force in the Western World in a Few Centuries (New York: Harper One, 1996), 57-58.

[32] Ibid., 59.

[33] Paula Fredriksen, Paul: The Pagan’s Apostle (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 2017), 54, 60.

[34] Stark, Rise of Christianity, 59.

[35] See, generally, James D.G. Dunn, The Partings of the Ways: Between Christianity and Judaism and their Significance for the Character of Christianity (London: SCM Press, 1991); cf. Paula Fredriksen, “What ‘Parting of the Ways’? Jews, Gentiles, and the Ancient Mediterranean City,” in Adam H. Becker and Annette Yoshiko Reed, The Ways that Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (Mohr Siebeck, 2003), 35-63.

[36] Stark, Rise of Christianity, 59-62.

oom spreading among first-century Jews of all social classes. Writers steeped in such an apocalyptic interpretation of restoration theology would have been well-placed to serve as “organic intellectuals” and publicists for the embryonic Jesus movement in major urban centres throughout the empire.

oom spreading among first-century Jews of all social classes. Writers steeped in such an apocalyptic interpretation of restoration theology would have been well-placed to serve as “organic intellectuals” and publicists for the embryonic Jesus movement in major urban centres throughout the empire. have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham (Matt. 3:9). John expects the carnal pride displayed by these representatives of the Jewish religious establishment to be followed by a fall. Anticipating Paul’s mission to the Gentiles (Rom. 11:11), John is certain that the ethnoreligious movement soon to be launched by Jesus will produce so many children of Abraham (according to the spirit) that Abraham’s seed (according to the flesh) will be provoked to jealousy. In effect, when tempting Jesus to flaunt his miraculous powers as the Son of God, Satan serves as a stand-in for the Pharisees and Sadducees.

have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham (Matt. 3:9). John expects the carnal pride displayed by these representatives of the Jewish religious establishment to be followed by a fall. Anticipating Paul’s mission to the Gentiles (Rom. 11:11), John is certain that the ethnoreligious movement soon to be launched by Jesus will produce so many children of Abraham (according to the spirit) that Abraham’s seed (according to the flesh) will be provoked to jealousy. In effect, when tempting Jesus to flaunt his miraculous powers as the Son of God, Satan serves as a stand-in for the Pharisees and Sadducees.

headquartered in Washington D.C. and New York, but he is also critical of the evangelical Protestant establishment. Before publication of his best-selling book on Christian nationalism, Wolfe had already written a series of online articles deploring “the sorry state of evangelical rhetoric.”

headquartered in Washington D.C. and New York, but he is also critical of the evangelical Protestant establishment. Before publication of his best-selling book on Christian nationalism, Wolfe had already written a series of online articles deploring “the sorry state of evangelical rhetoric.”