“One learns from Confessions of a Mask how Mishima put “Circassians” (white boys) to the sword by the dozen in his dreams.”

Henry Scott Stokes, The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima

“Mishima is more a figure of parody than a force of politics.”

Alan Tansman, The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism

I read with great interest Guillaume Durocher’s recent Unz Review article on Yukio Mishima’s commentary on the Hagakure, the eighteenth-century guide to Bushido, or Japanese warrior ethics. I rate Durocher’s work very highly, and as someone who once shared his interest in Mishima, and Japanese culture more generally, I expected the piece to be well-informed, insightful and provocative. Much as I was intrigued by Durocher’s piece, I think the Dissident Right would benefit from an alternative view of Mishima, and perhaps also the subject of Japanese culture in the context of European rightist sensibilities, especially when right-wing treatments of Mishima other than Durocher’s (which is suitably measured in the assessment of Mishima’s fiction) tend towards hagiography. In the following essay, I offer not necessarily a rebuttal or rebuke of Durocher, but an alternative lens through which to view the Japanese author, his life, and politics. Since a movement’s choice of heroes can have an impact on its spirit and ethos, the following should be considered an attempt at spiritual ophthalmology, or the bringing of certain perspectives into clearer focus. This clearer focus, I argue, can only lead to the conclusion that Mishima was a profoundly unhealthy and inorganic individual who should be regarded as anathema to European nationalist thought.

My first introduction to Yukio Mishima came several years ago in the form of a recording of a 2011 lecture delivered in London, by the late Jonathan Bowden, at the 10th New Right meeting. Bowden was an exceptional orator, yet to find an equal in the current crop of dissident right leaders. In fact, as we move further and further into patterns of YouTube-based “content producing” I fear that oratory of Bowden’s type may become an increasingly rare art. One of Bowden’s great strengths as a speaker was the ability to take dense topics and biographical overviews and reduce them to an hour or so of dynamic, entertaining, and extremely accessible commentary. Those in the audience, or listening in other forms, found it impossible for their attention to wander. A downside to Bowden’s oratory was that it didn’t translate quite as well onto paper, often following Bowden’s stream of consciousness rather than more logical and structured progression, with the result that one laments that Bowden didn’t focus also on a more formal type of scholarship that would surely have constituted a monumental and lasting bequest to the movement he devoted so much to. As it stands, recovering Bowden’s legacy has for the most part been the task of tracking down lost recordings of his speeches, a task that Counter-Currents have admirably taken the lead in.

Prior to listening to Bowden on Mishima, I had already established an interest in Japanese history and culture. I trained for several years in jiu-jitsu, spent a great deal of time in my early 20s reading the works of D. T. Suzuki and Shunryu Suzuki on Zen Buddhism (the former also had some interesting and sympathetic things to say on National Socialism and anti-Semitism), and Brian Victoria’s 1997 Zen at War remains one of the most interesting works on the history of religion and warfare I’ve yet had the pleasure to read. Somehow, however, Mishima escaped my attention until Bowden’s lecture, which really offered only the most raw and basic of introductions to the man. Bowden presented Mishima as a rightist thinker but never quite explained why. He indicated that Mishima had some relevance for the European right but couldn’t articulate how. The lecture only clumsily situated Mishima within near-contemporary Japanese culture, and Bowden himself evinced equivocation and incomprehension on the reasons why Mishima undertook his now infamous suicidal final action. Who was Mishima? Why was he relevant? In a bid to follow up these loose ends, and trusting Bowden that the effort would be worthwhile, I spent around a year making my way through Mishima’s fiction, biographies, scholarship, and other forms of commentary on Mishima’s life and death. The result of my research was a deluge of notes, many of which will now make their way into this article, and profound disappointment that such a figure should ever have been promoted in our circles.

Explaining how and why Mishima came to be promoted in corners of the European Right requires that one confront what could be termed “the Mishima Myth,” or the vague and propagandized outlines of what constitutes Yukio Mishima’s biography and presumed ideology. The Mishima Myth runs something like this:

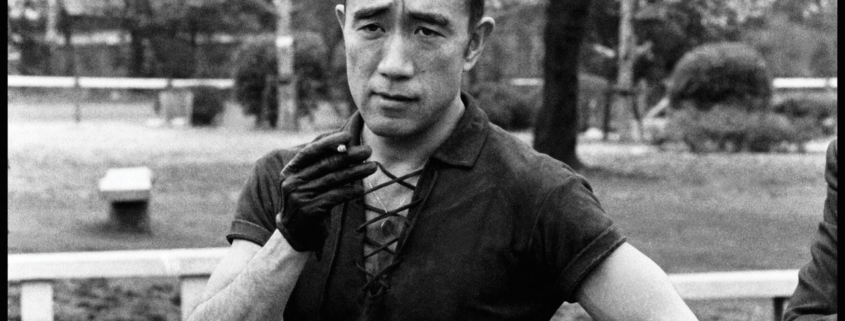

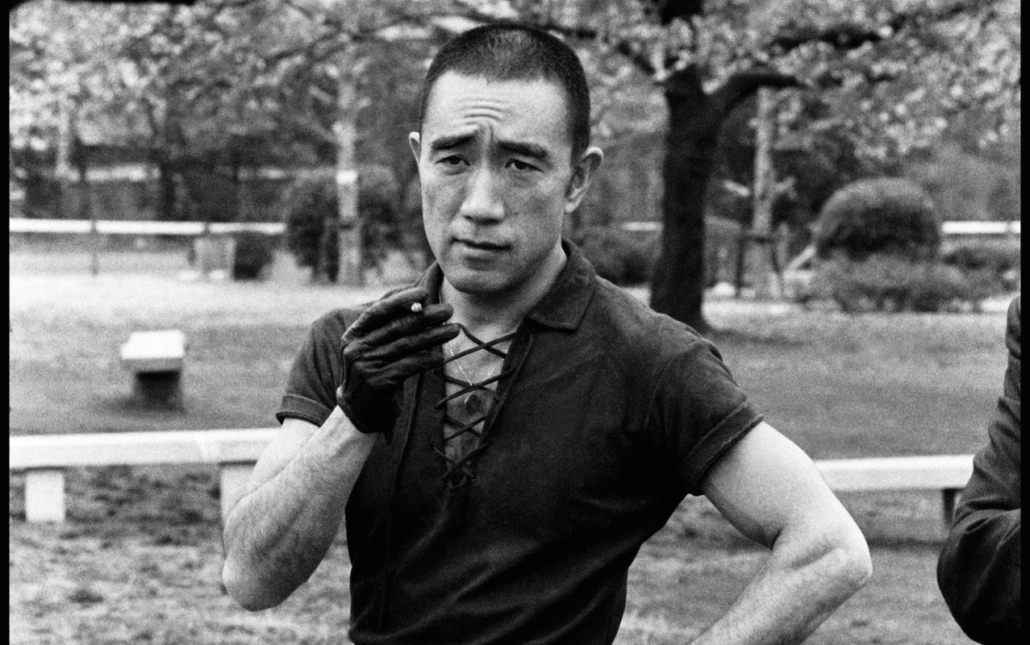

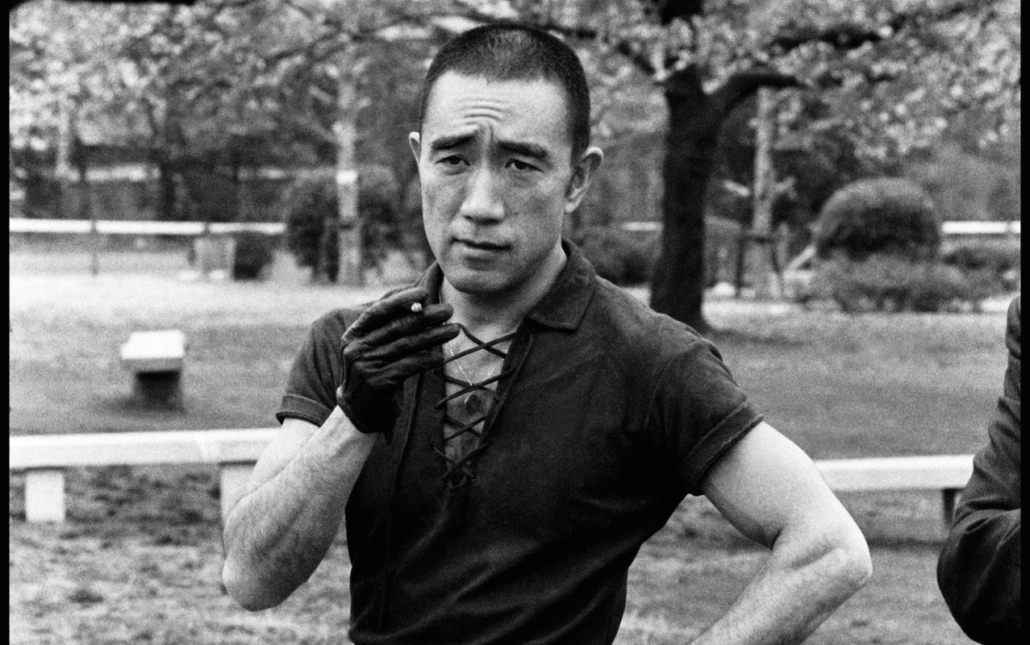

Yukio Mishima was a gifted and prolific Japanese author and playwright who became profoundly disillusioned with the political and spiritual trajectory of modern Japan; influenced by Samurai tradition and Western thought, especially the philosophy of Nietzsche, he embarked on a program of radical self-improvement; he took up bodybuilding and formed his own 100-strong private army — the Shield Society; he led this army in an attempted coup at a military base, taking a very senior officer hostage, and demanded that all troops follow him in rejecting the post-war constitution and supporting the return of the Emperor to his pre-war status as deity and supreme leader; finally, rejected and ridiculed by the troops, he took his life via seppuku, ritual disembowelment in the tradition of the Samurai.

Occasionally, for added effect, rightist promoters of Mishima will add that he wrote a 1968 play titled My Friend Hitler, which, despite the provocative title, is politically middling, and has been interpreted as anti-fascist as often as it has been as fascist. Taken together, one supposes that the relevant factors here are that Mishima was an authoritarian, monarchist “Man of Action” who seized control of his own life and attempted to divert his nation away from empty consumerism (cue applause). Thus, in the Mishima Myth, rather than focusing on his actual writings on fascism and politics (which are in any event very few in number), Mishima’s ideology is read from selected chapters of his life, especially his final actions. Mishima becomes a man of the right because he was Mishima, because of what he did. This, so the narrative goes, is why he should be relevant to us.

A critique of the Mishima Myth is therefore necessarily ad hominem, since there is a glaring absence of ideas to argue against and since the myth is merely a composite of slices of edited and heavily sanitized biography. Despite an abundance of English-language biographies, rightist promoters of Mishima rarely engage in serious exploration of Mishima’s life, preferring to focus on hagiographic presentations of selected episodes, especially their interpretation of the dramatic death. This should be the first cause of caution, and it was certainly mine. The primary reason for this evasion, as I was to find out, is profound embarrassment, since Mishima’s life is thin on right-wing politics, or for that matter politics of any description, and rather heavy on homosexual sadomasochism (which is far from the only questionable aspect of Mishima-ism). But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s start at the beginning.

Yukio Mishima was born Kimitake Hiraoka on January 14 1925, into an upper middle-class family. One of the first things that struck me about Mishima’s life, and especially his childhood, is that it has attracted swathes of psychoanalysts,[1] the reason being that he is an important and visible example of what these writers perceive to be the link between oppressive and abusive childhoods, latent homosexuality, sadism, masochism, and authoritarian and fascist politics. Indeed, if one makes the argument that Mishima was in fact a fascist, then one begins to consent to some of the central theses of the Frankfurt School. Mishima certainly had a strange and psychologically distorting childhood, and I concur with Sadanobu Ushijima’s conclusion that it resulted in Mishima suffering most of his life from a personality disorder involving “recurrent episodes of depression with severe suicidal preoccupation.”[2]

According to Henry Scott Stokes, in my opinion Mishima’s best biographer as well as being the only Westerner invited to his funeral, almost as soon as Mishima was born his grandmother (Natsuko) “resolved to take personal responsibility for his upbringing and virtually kidnapped the little boy from his mother,” raising the child almost entirely in her sickroom.[3] Natsuko brought up Mishima “as a little girl, not as a boy,” and he was forced to stay inside, was prohibited with playing with most of his environment, and was told to be almost completely silent due to his grandmother’s complaints of constant head pain.[4] After some years, his mother was permitted to take him outside, but only when there was no wind.[5] There is some suggestion that he was beaten, or otherwise severely psychologically abused, with the result that he suffered a sequence of psychosomatic illnesses involving the retention of urine. There is also some suggestion of sexual abuse or “obscene” treatment at the hands of his grandmother’s nurse. Quasi-incestuous closeness in indicated by his later description of his grandmother as a “true-love sweetheart”, and on his death his mother described him as her “lover.”[6] Mishima was generally regarded by those around him as “an unusually delicate child.”[7]

In keeping with scientific studies strongly suggesting that dressing, or otherwise treating, young boys as girls can induce homosexuality,[8] and studies showing that homosexuals are more likely than the sexually normal to be predisposed to “brutal” violence[9] (to say nothing of what anecdotally appears to be a disproportionate preponderance of homosexual serial killers and cannibals), Mishima would later write in his semi-autobiographical Confessions of a Mask (1949) that he had homosexual fantasies from a young age and that many of these were sadistic in nature. At this point I should pause and concede that the British “anti-Fascist” collective operating as Hope Not Hate have described me as perhaps the most “homophobic” “far right commentator” in the Dissident Right, as well as simplifying my perspective as framing “homosexuality and modern conceptions of gender as socially constructed as a symptom of societal decay, and LGBT+ rights as a tool of a Jewish conspiracy to undermine white society. This vein of thinking sometimes even results in open calls for the expulsion or violent eradication of LGBT+ people.”

This may or may not be an entirely accurate representation of my views, but the point I want to make here is that my critique of Mishima isn’t based on his homosexuality qua homosexuality, since the argument could be made by some that a homosexual fascist is still a fascist (though such arguments could be easily problematized and I will later critique his “fascism” in and of itself). Piven remarks that there has long been a “Mishima cult” in France (perhaps Durocher can confirm), adding “though his following outside Japan consists largely of gay populations who champion him.”[10] My argument against the Mishima myth is mainly that if key aspects of his biography, including the death, are linked significantly more to his sexuality than his politics, then this is grounds to reconsider the worth of promoting such a figure, already non-White and with no significant Western cultural impact, within the Dissident Right.

Mishima was “eternally excluded from the lives of ordinary men and women,” and developed early fantasies about taxi drivers, bartenders, but especially soldiers.[11] He was particularly fixated on the idea of dying soldiers and death generally, and “the violent or excruciatingly painful death of a handsome youth was to be a theme of many of his novels.”[12] In childhood, Mishima enjoyed playing dead, and he had eroticized notions of suicide from early adolescence. In his own words, he had a “compulsion toward suicide, that subtle and secret impulse.”[13] His first erotic experience appears to have been masturbating to a print of Guido Reni’s St. Sebastian, which depicts the semi-nude and bleeding saint bound to a tree and impaled with arrows. Mishima would later explain that he “delighted in all forms of capital punishment and all implements of execution so long as they provided a spectacle of outpouring blood.”[14] Stokes comments that “In Mishima’s aesthetic, blood was ultimately erotic.” Mishima fantasized about wounded, dying soldiers, imagining “I would kiss the lips of those who had fallen to the ground and were still moving spasmodically.”[15] He day-dreamed about execution devices studded with daggers, designed to shred the bodies of young men, and had a “fantasy of cannibalism” in which he fed on an athletic youth who had been “stunned, stripped, and pinned naked on a vast plate.”[16] Jerry Piven observes that Mishima’s fiction is replete with “innumerable fantasies of raping and killing beautiful young boys, of scenes of masturbating to images of slain men, of ceaseless loathing for despicable women.”[17]

St. Sebastian by Guido Reni (c. 1625)

In Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima (1994), Roy Starrs comments:

Few writers since the Marquis de Sade himself have made a more public and provocative “performance” of their “perverse” sexuality. … He found himself aroused by pictures not of naked women but of naked men, preferably in torment. Again he finds that homosexual pleasure is inextricably linked, for him, with sadistic pleasure, and he indulges in the most outrageous fantasies of managing a “murder theatre” in which muscular young men are slowly tortured to death for his amusement.[18]

Mishima read both Freud and the works of the Jewish sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, and concurred with the latter (also a homosexual and transvestite) that pictures of the dying St. Sebastian were a favorite among homosexuals, with Mishima himself arguing that “the homosexual and sadistic urges are inextricably linked.”[19] Far from the image of the austere Samurai, as he approached middle age the increasingly bipolar Mishima was known to dance in gay bars with a 17-year-old drag queen,[20] and once flew to New York solely for the purpose of finding a White man who would be sexually “rough” with him. His former lovers recall how he “liked to pretend he was committing seppuku,” making them watch, before asking them to stand over him with a sword as if about to behead him. He would pull out a red cloth, that he would pull across his abdomen explaining this was his “blood and guts.”[21] Mishima once described himself as “strangely pathetic.”[22] Durocher may well be correct in his review of Mishima on the Hagakure that “Above all, Mishima would have men live full, worthy, and noble lives,” but readers should by now be aware of why I felt an alternative lens needed to be introduced to our perspective.

A theory thus presents itself that Mishima’s carefully orchestrated death was a piece of homosexual sadomasochist theatre rather than anything political, let alone fascistic or in the tradition of the Samurai. In order to parse this question more fully, it’s necessary to examine Mishima’s politics and spirituality, or what can at least be discerned in that direction.

One of the remarkable things about Mishima is that he seems hardly political at all. His fiction, denounced by early critics of all political hues as full of “evil narcissism” possessing “no reality,” is almost entirely devoid of ideology. (Durocher appropriately mentions how he tried to, and wanted to, like Mishima’s novels but couldn’t.) As such, Mishima is a pale shadow of ultra-nationalist literary contemporaries like Shūmei Ōkawa, Hideo Kobayashi, and Yasuda Yojūrō. Confessions of a Mask, his most autobiographical text and a style of novel (shishosetsu) that Kobayashi especially loathed as ‘popular’, “had nothing to say in it about political events that had influenced his life. … He was regarded as apolitical by his contemporaries.”[23] He was neither politically involved nor possessed of any real depth of feeling on political matters until the 1960s, when he was around 40 and becoming increasingly pessimistic and depressed — mainly because he was ageing and was disgusted and horrified by old age.[24] In his commentary on the Hagakure, Mishima would inflect his own anxieties about ageing and his own predilection for youthful suicide fantasies by telling his readers they should live for the moment and be content with a short life, and one gets the sense of personal inflections again when he informed his readers that “homosexual love goes very well with the Way of the Warrior.”[25] Otomo remarks that Mishima’s relationship to the Hagakure was simply peculiar and largely artificial, pointing to better, more authentic, examples of Bushido ethics and exploits such as Budoshoshinshu and the Kōyō Gunkan, and remarking on the Hagakure:

Ironically enough, the text is evidence of the absence of the code. It is an empty style that can be borrowed by anyone at any time of history and it no longer signifies a core culture of an Oriental entity called Japan. In fact, it has never signified as such except in one man’s nostalgia.[26]

In reality, and despite his self-presentation as the embodiment of the Hagakure, Mishima was strangely un-Japanese, something remarked upon by Stokes (“he was remarkably un-Japanese”)[27], who met him several times, and as evidenced in various aspects of Mishima’s life. Ryoko Otomo observes that, in a departure from the Zen Buddhism of the Samurai, Mishima, “was an affirmed atheist.”[28] What Mishima did in fact see in Zen and the Hagakure, so far as can be determined from his fiction and statements to journalists, was a dark and profound nihilism — something that any Zen master, including D. T. Suzuki who in one of his seminal texts has a chapter titled “Zen is not Nihilistic”, would argue is anathema to authentic Zen conceptions of “the Void.” When he became financially successful, Mishima set about building a large, Western-style, “anti-Zen” house, and Zen masters he associated with later remarked Mishima made “no profound study of philosophy.”[29] Mishima knew nothing of nature, being a decadent urbanite, and was unlike many Japanese in being ignorant of the most basic botany. Once, when accompanying a friend in the countryside, he was shocked and confused at the noise of frogs.[30] He once told reporters that his average day was spent with gym activity followed by lounging around a house regarded by his neighbors, and even its architect, as “gaudy,” “in jeans and an aloha shirt.”

Mishima went through with a hasty marriage of convenience to satisfy his dying mother, fathering two children that, in the style of the worst ghetto-dwellers, he was largely absent from. In fact, in several of his novels, especially Forbidden Colors which is replete with what Stokes calls “morbid sexuality,” he expresses contempt for children, families, and the normal, non-homosexual familial structure that is the backbone and future of all societies and civilizations:

Go to a theater, go to a coffeehouse, go to the zoo, go to an amusement park, go to town, go out to the suburbs even; everywhere the principle of majority rule is lording about in pride. Old couples, middle-aged couples, young couples, lovers, families, children, children, children, children, children and, to top it off, those blasted baby carriages—all of these things in procession, a cheering, advancing tide.

By contrast, as a homosexual, Mishima nurtured fantasies of himself as a member of an elitist minority.

Ideologically, Mishima was clumsy and confused at best. He believed that fascism and Freudian psychology were ideologically related,[31] and believed in resurrecting a Japanese imperialism that would make room for parliamentary democracy.[32] He insisted, meanwhile, that “fascism will be incompatible with the imperial system.” Moreover, he argued that Japanese right-wingers “did not have to have a systematised worldview,” perhaps because he had none himself, and that they “nevertheless have nothing to do with European fascism.”[33] By the early 1960s, Mishima was a writer of decadent romantic fiction so politically weak, and tendentiously left-wing, that he was targeted with death threats by right-wing paramilitaries.[34] Eventually, some time in the late 1960s and despite having no real depth of feeling for Shinto religion, Mishima decided that it would be a good idea if the Emperor was returned to his pre-war status as a deity, prompting Sir John Pilcher, British Ambassador to Japan to declare Mishima’s fantasy of placing himself “in any relationship to the Emperor” as “sheer foolishness.”[35] Mishima, of course, never explored the Emperor’s role in World War II in any depth, and his chief fixation appears solely to have been the decision of the Emperor to accede to Allied demands and “become human.” Although Mishima became increasingly vocal on this issue, and even started taking financial donations from conservative politicians to establish a small paramilitary grouping consisting of lovers and fans, “he never defined his positions clearly,” and was so poor at articulating his ideas to troops during his coup attempt that he was simply laughed at by gathered soldiers.[36] Whether or not Mishima was fully sincere is, of course, another matter, though his suicidal coup attempt came very shortly after literary career declined so rapidly that friends wrote to him “telling him that suicide would be the only solution.”[37] Suicide in Japanese culture is of course also crucial to this discussion and will be explored below.

Mishima’s purported militarism is worthy of some attention. I come from a military family, and have many friends in the military. One of the things that’s always irritated and amused me is the difference between how actual service personnel discuss themes such as “being a warrior” or combat more generally in comparison to military fantasists. Among the former, there always exists a wry, sober, even bittersweet outlook. Among the latter, one is apt to find much talk of glory and conquest, but little action. Mishima was surely a military fantasist, who even by his own admission had a sexual fetish for the white gloves worn with the Japanese uniform,[38] and lied during his own army medical exam during the war in an effort to avoid military service: “Why had I looked so frank as I lied to the army doctor? Why had I said that I’d been having a slight fever for half a year, that my shoulder was painfully stiff, that I spit blood, and that even last night I had been soaked by a night sweat? … Why had I run so when I was through the barracks gate?”[39]

When the bombs fell during the war, Mishima recalled, “that same me would run for the air-raid shelters faster than anyone.”[40] Stokes suitably comments that “had he served in the army, even for a short while, his view of life in the ranks would have been less romantic, later in life,” but that instead “Mishima stayed home with his family, reading No plays, the dramas of Chikamatsu, the mysterious tales of Kyoka Izumi and Akinari Ueda, even the Kojiki and its ancient myths.”[41] When he eventually formed his own paramilitary organisation, he dressed them in “opéra bouffe uniforms which incited the ridicule of the press,” and Starrs comments: “He was no more a true ‘samurai’ than he was a true policeman or airforce pilot, in whose garb he also had himself photographed. The ‘samurai’ image was simply one of Mishima’s favourite masks — and also one of his most transparent.”[42]

One could add speculations that Mishima’s military fantasies were an extension of his sexual fixations, including a possible attempt to simply gain power over a large number of athletic young men. But this would be laboring an all-too-obvious point. More soberly, one could merely point to the ridiculous notion of a military coup being led by a bipolar, draft-dodging shut-in (Hikikomori) who, when confronted during the action itself, witnessed the beginning and end of his fighting career when he hacked frantically at a handful of unarmed men with an antique sword. The Jewish academic and Japan scholar Alan Tansman might well be a sexual pervert himself, but it’s difficult to disagree with his assertion that “Mishima is more a figure of parody than a force of politics,”[43] and attempts to link Mishima with our worldview only provide further grist for the Jewish mill.

Since Mishima’s writings and actions are politically opaque at best, it is little wonder that most attention from his propagandists has focused on the dramatic and quasi-traditional method of suicide, which is often portrayed as representing the utmost in honor, masculine courage etc. Such accounts, of course, normally omit the fact Mishima rehearsed his suicide for decades in the form of gay sex games, and was essentially a gore fetishist. A broader problem exists, however, in the nature of Western appraisal of seppuku, and suicide in Japanese culture more generally. The most enlightening piece of work I’ve read in this sphere has been that of the late Toyomasa Fuse (1931–2019), Professor Emeritus at York University and probably the world’s leading expert on suicide among the Japanese. In Suicide and Culture in Japan: A Study of Seppuku as an Institutionalized Form of Suicide, Fuse explains that suicide in Japan essentially originates from a servile position within a highly anxious and neurotic society. Needless to say, this is far from healthy and praiseworthy behavior. He describes seppuku as a form of “altruistic suicide” and an expression of “role narcissism,” it being a

Response to a continued need for social recognition resulting from narcissistic preoccupation with the self in respect to status and role. … Many Japanese tend to become over-involved with their social role, which has become cathected by them as the ultimate meaning in life. … Shame and chagrin are so extreme among the Japanese, especially in a perceived threat to loss of social status, that the individual cannot contemplate life henceforth.[44]

There is little question that seppuku had a place among the samurai, but the actual nature of its practice over time was complex and was successively reinterpreted, alternating between a voluntary way of recovering honor, and a form of capital punishment (peasants, meanwhile, were simply boiled alive). It also alternated in form, involving varying types of cut to the belly, and sometimes involving no cut to the abdomen at all — the individual would ceremonially reach for a knife before being quickly beheaded. Starrs observes that while misguided Westerners have “naively accepted” Mishima’s seppuku as being “in the best samurai tradition,”[45] it was simply Mishima’s own variation on a theme — the same theme that witnessed hundreds of servile Japanese slit their bellies in front of the imperial palace at the end of the war because of their embarrassment at failing the Emperor. Again, we must question, at a time when we are trying to break free from high levels of social concern and shaming in Europe, whether it is healthy or helpful to praise practices originating in pathologically shame-centered cultures.

As Fuse notes, the traditional European response to seppuku has been disgust, not solely at the physical act itself but because of the servile psychological and sociological soil from which it originates. Because of the difference in mentalities, there is a complication in how concepts such as honor and bravery translate in this particular instance. Seppuku certainly appears to be easier to undertake for a Japanese than for a European. Mishima himself, to give the devil his due, didn’t equivocate in his pursuit of the most brutal methodology. His own wound was found to be five inches across and, in places, two inches deep.[46] Those knowledegable enough in older times would make a cut so as to cut a renal or aortic vein, leading to such catastrophic blood loss that death would be almost instantaneous. Mishima doesn’t appear to have had such knowledge, spilling his intestines out in agony while three successive attempts (by a subordinate and rumored lover) were made to behead him, one opening up a massive wound on his back instead.

Conclusion

The facts surveyed here surely point out the inadequacies of the Mishima Myth as presented in corners of the European Right. I listened again to Bowden’s lecture just yesterday, and laughed out loud at Bowden’s brief gloss of Mishima’s catastrophic childhood (“he was a slightly effeminate child”). Unfortunately, because Bowden spoke more often than he compiled serious research, it’s impossible to determine if Bowden was a conscious promoter of Mishima propaganda, or an earnest but ill-informed believer in the Mishima Myth. I simply don’t know the extent of Bowden’s reading in the matter. Like Durocher, I’ve also watched Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, though I found it to be a cheesy, dated, and rather manipulative hagiography rather than a masterpiece. Durocher comments “You’re either the kind of boy who is challenged, energized, and inspired by this sort of film, or perhaps you’re not a boy,” which I can only regard as laden with irony given that the film’s subject was raised as a girl and once remarked, on being expected to act like a boy: “the reluctant masquerade had begun.”[47] Schrader’s documentary is also highly sanitized; according to Stokes this is due to the tight control that Mishima’s widow and extended family had over the production, and their concern about potential for embarrassment.[48] One small scene showing Mishima in a gay bar was enough for the family to block distribution in Japan, and they even invested money in paying Takeshi Muramatsu to write a 500-page biography, the central proposition of which was to try to convince the Japanese public that Mishima was heterosexual and had merely spent his life, to quote Stokes, “posing as a sodomite.” Rather predictably, the text failed to convince anyone, though it probably salved the family’s pride a little to know that it was out there.

We come back to the central questions of how and why Yukio Mishima should be relevant to us. No answers can be found in the life, politics and actions of a figure not only non-European and profoundly un-fascistic, but who was also strangely un-Japanese. I contend that there is simply nothing genuine to learn from him, and few people who have written in support of Mishima can point to anything tangible beyond the amorphous outlines of the Mishima Myth and a film heavy on style and low on authenticity. There is no single piece of text, no treatise, and no piece of authenticity beyond a final, radically un-European and sadomasochistically-inspired act of self-destruction and death-embracing nihilism. Mishima’s monarchism was servile and parodic, his militarism homoerotic, disingenuous and ludicrous, and his death-as-political-statement was psychosexual and ultimately lacking in logic. Otomo is probably correct in viewing the coup attempt more as a sexually inspired method of “politicising art rather than expressing a belief in ultra-nationalism.”[49]

The question thus arises as to whether associating ourselves with such a figure, surely a clownish homoerotic wignat in today’s vernacular, brings more positives or negatives, both within the Dissident Right and within broader considerations of “optics” or public image. In particular, we should question whether we want to place our politics in a nexus that involves, to borrow the terminology of the Japan scholar Susan Napier, “the interrelationship between homosexuality, politics, and the peculiar form of violence-prone psychosexual nihilism from which Mishima suffered.”[50] I’d argue in the negative.

Members of the Dissident Right with an interest in Japanese culture are encouraged to take up one or more of the martial arts, to look into aspects of Zen, or to review the works of some of the other twentieth-century Japanese authors mentioned here. Such endeavors will bear better fruit. Above all, however, there is no comparison with spending time researching the lives of one’s own co-ethnic heroes and one’s own culture. As Europeans, we are so spoiled for choice we needn’t waste time with the rejected, outcast, and badly damaged members of other groups.

[1] See, for example, Abel, T. (1978). Yukio Mishima: A psychoanalytic interpretation. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 6(3), 403–424; Piven, J. (2001). Mimetic Sadism in the Fiction of Yukio Mishima. Contagion: Journal of Violence, Mimesis, and Culture 8, 69-89; McPherson, D.E. (1986). A Personal Myth—Yukio Mishima: The Samurai Narcissus. Psychoanalytical Review, 73C(3):361-378; Jerry Piven (2001). Phallic Narcissism, Anal Sadism, And Oral Discord: The Case Of Yukio Mishima, Part I. The Psychoanalytic Review: Vol. 88, No. 6, pp. 771-791; Piven, J. S. (2004). The madness and perversion of Yukio Mishima. Praeger Publishers/Greenwood Publishing Group; Cornyetz, N., & Vincent, J. K. (Eds.). (2010). Perversion and modern Japan: psychoanalysis, literature, culture. Routledge.

[2] Ushijima, S. (1987), The Narcissism and Death of Yukio Mishima –From the Object Relational Point of View–. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 41: 619-628.

[3] H. S. Stokes The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima (Cooper Square Publishers; 1st Cooper Square Press Ed edition, 2000), 40.

[4] Ibid., 41.

[5] Ibid., 47.

[6] Ibid., 47.

[7] Ibid., 42.

[8] John Money, Anthony J. Russo, Homosexual Outcome of Discordant Gender Identity/Role in Childhood: Longitudinal Follow-Up, Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Volume 4, Issue 1, March 1979, Pages 29–41.

[9] Mize, Krystal & Shackelford, Todd K., Intimate Partner Homicide Methods in Heterosexual, Gay, and Lesbian Relationships Violence and Victims, 23:1.

[10] J. Piven The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima (Westport: Prager, 2004), 2.

[11] Stokes, 43, 44.

[12] Ibid., 44.

[13] Ibid., 58.

[14] Ibid., 61.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] J. Piven The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima (Westport: Prager, 2004), 3.

[18] R. Starrs Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1994), 35.

[19] R. Starrs (2009) A Devil of a Job, Angelaki: Journal of the Theoretical Humanities, 14:3, 85-99, 85 & 87.

[20] Stokes, 103 & 136.

[21] Starrs, A Devil of a Job, 89.

[22] Stokes, 91.

[23] Ibid., 95.

[24] Ibid., 95 & 102.

[25] Ibid., 266.

[26] Ryoko Otomo, The Way of the Samurai: Ghost Dog, Mishima, and Modernity’s Other, Japanese Studies 21 (1), 31-43, 41.

[27] Stokes., 5.

[28] Otomo, 40.

[29] Stokes, 278.

[30] Ibid., 110.

[31] Starrs, Deadly Dialectics, 24.

[32] Otomo, 39.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Stokes., 295.

[35] Ibid., 277.

[36] Ibid., 273.

[37] Ibid., 281.

[38] Ibid., 57.

[39] Ibid., 81.

[40] Ibid., 76.

[41] Ibid., 81.

[42] Starrs, Deadly Dialectics, 7.

[43] Tansman, A. (2009). The Aesthetics of Japanese Fascism. University of California Press, 257.

[44] Fusé, T. Suicide and Culture in Japan: A Study of Seppuku as an Institutionalized Form of Suicide Social Psychiatry (1980) 15: 57, 61.

[45] Starrs, Deadly Dialectics, 6.

[46] Stokes, 34.

[47]Ibid., 48.

[48] Ibid., 267.

[49] Otomo, 40.

[50] Napier, S. (1995). Reviewed Work: Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima by Roy Starrs Monumenta Nipponica, 50(1), 128-130.