Those who are acquainted with the many books and films produced recently about the 20 July 1944 plot to assassinate Hitler led by Count Claus Schenk von Stauffenberg may have the impression that the plot was a result of the aversion of the German aristocracy to the political ambitions of a commoner like Hitler. In fact, Stauffenberg’s failed attempt was only the last of a series of attempts to assassinate Hitler that originated from General Ludwig Beck (1880–1944). Beck was not an aristocrat but belonged to the officer class and resigned his post as Chief of Staff of the German Army in August 1938 mainly on account of his disagreement with Hitler’s aggressive foreign political aims.

The German aristocracy itself was incorporated into the National Socialist movement from the twenties on without much difficulty, even though some of the aristocratic National Socialists had to tolerate the contempt of peers who were opposed to the socialist aspects of Hitler’s government. According to Stephan Malinowski,[1] in all, about 300 noble families of the lower aristocracy based in Prussia contributed about 3,600 members to the National Socialist Party, and the number of adherents from the upper ruling families rose from 70 in the thirties to around 270 by 1945. Most of these were Prussian and Protestant rather than Bavarian and Catholic, since the Bavarian Catholic aristocrats were dedicated to the House of Wittelsbach, whose crown prince, Rupert of Bavaria, was firmly opposed to Hitler and was exiled in December 1939 to Italy while other members of his family were interned for some years in concentration camps.

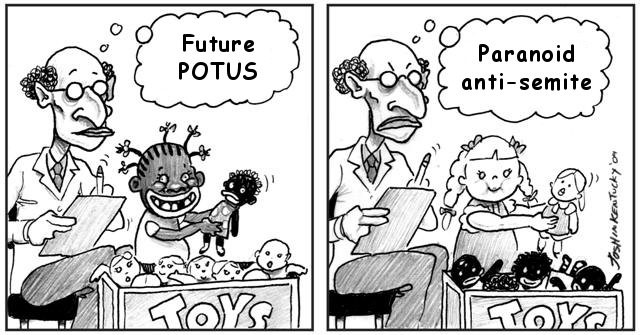

It is true that Stauffenberg and some of his fellow conspirators in the 20 July plot were shocked by Hitler’s extreme persecution of the Jews, but it cannot be clearly said that all of the conspirators were impelled by philo-Semitic sentiments since the German aristocracy was, in general, anti-Semitic and anti-Marxist like Hitler himself. Count Wolf-Heinrich Helldorf (whose 1934 essay is presented here) was in fact a vigorous anti-Semite in the thirties[2] and may even have played a part in the organisation of the Kristallnach riots, though he eventually joined the conspirators led by Stauffenberg. That all the aristocratic National Socialists did not revolt against Hitler is also clear from the fact that the editor of the collection of essays here presented, Prince Friedrich-Christian of Schaumburg-Lippe, remained a proud National Socialist even after the war.

The following three extracts from the collection of nine essays by aristocratic National Socialists that was edited by Prince Friedrich-Christian of Schaumburg-Lippe, Wo war der Adel? (Where was the aristocracy?, Berlin: Zentralverlag, 1934), show that many of the aristocrats indeed welcomed the opportunity given to them by the National Socialist movement to renew their own aristocratic estate after it had been destroyed alongside the German monarchy in 1918. In turn, the elevated codes of conduct of the aristocrats as traditional rulers of the German domains helped to strengthen the chivalrous image that is often associated with the German military of the Third Reich. It is true, however, that the SS as developed by Himmler from 1929 came to represent the real elite formation of the Third Reich since it was originally created as a bodyguard for Hitler and expressed more directly the dedication to the Führer that was the hallmark of the entire Third Reich. The members of the old aristocracy were absorbed into the SS, as well as into the earlier SA, without much strain since the old and the new elites had in common a desire to renew Germany after its devastating defeat in World War I. One feature that may have been novel, however, about the involvement of the aristocrats in the National Socialist movement is the more socialist conception of themselves that they now manifested, no longer as superior leaders of an anonymous population of subjects but as close collaborators with the latter in the task of building a new German empire.

* * *

Count Bernhard von Solms-Laubach [1900–1938]

Director of the National Theatre,

Standartenführer[3]

The Aristocracy is dead – Long live the Aristocracy!

We do not wish to be sentimental, we admit openly that which everybody, however, already knows. That there is no aristocracy any longer in Germany that in its entirety is still capable of representing a clear ideal. The aristocracy is dead because it has killed itself. We stand before a sad remnant, before a burial mound that has been raised up with effort but without jewels, and unlamented, to which one has given the impressive name ‘German aristocratic society’.

And there was once a time when all the names had a strong resonance and an inner significance, when all the families had a calling in the nation, all the names and all the families as they are neatly recorded today in peerage lists and Gotha pocketbooks[4] as though for museum purposes. There was a time when the German aristocracy was a living fact, when there was bound with the aristocratic name a sacred responsibility towards the people, when the German aristocracy was the bearer of a quite definite worldview, an idealistic worldview in which one’s own advantage could have no meaning compared to the duty to serve to the utmost the people, the country, the state and its representatives. Then the aristocrat stood naturally at the very front, as a spearhead, for the affairs of his people, ready to give up and sacrifice not only his life but also his possessions, if that might help. Everywhere in the Empire they were based in their residences and castles like the conscience of the people, watchmen and preachers, but always fighters for the existence of the Holy Roman Empire, each alone for himself, bound to one another only through the common goal – and one who did not acknowledge this goal through fighting and sacrificing and made it his own was considered a traitor, an apostate. Germany owes its life to this aristocracy.

But if Germany had depended on the present-day aristocracy it would have died along with it. The aristocrats still dwell everywhere in the Reich in their residences and castles, but it is only due to the people that they are recognised as their conscience. They no longer watch over or preach and, if they fight, then it is in defence of their property or their vanity. Every aristocrat no longer stands by himself, today they are organised, but their organisation lacks any goal that rises beyond their selfish aims. Anyone of them that acknowledges the goal of his nation in fighting and sacrificing and internalises this is today a traitor, a renegade.

This all of us who, members of the German aristocracy based on our origin, were able to be incorporated into the National Socialist movement during the battle period must have experienced in a personal way to a sufficient degree. One should not today expunge the fact that we took up the fight in the movement under the express disapproval of our so-called peers, that we were fought and laughed at. If we felt it as obvious to fight when our nation is in the process of fighting for its life — perhaps because we were conscious of the responsibility and the duties transmitted to us from ancient times by our name, that is, because we belonged to the German aristocracy — the opinion of our aristocratic colleagues was the opposite, namely, that we became National Socialists in spite of belonging to the aristocracy. We were, considered from the intellectual viewpoint of the German aristocratic society, actually the traitors, the renegades, and would have been condemnable if we had not been granted extenuating circumstances on account of our idiocy. Besides, it was not in good taste. Politically one had to be a German nationalist, but that one was not a monarchist was an absurd thought. For the further pursuits of the really energetic there was available, besides, the Gentlemen’s Club and, for the others, country riding clubs and — one may perhaps add — leadership positions in the Stahlhelm.[5]

To express it briefly: the German aristocracy disgraced itself to death. It pathetically missed the last chance to prove its raison d’être. Here too exceptions confirm the rule. The question is hard and clear which the people today pose to you: Where were you aristocratic gentlemen when Germany perished? What did you do when the adversity became ever more unbearable? Where did you fight and what did you sacrifice? You thought of yourselves and how you could save yourselves! You thought of yourself and the welfare of your family and perhaps regretted the misery of the people, perhaps even found it depressing, but did nothing! Did nothing! And you dare to raise a claim even today to leadership?

The people have known you for long. I shall never be able to forget with what suspicion I was accepted into the National Socialist movement and in the SA on account of my name. With what mistrust the workers stood against me at first because they attributed to such a person everything bad rather than an honest National Socialist disposition. Remarkable how this mistrust, this suspicion accorded with the attitude of the aristocratic society members! National Socialist even though one is aristocratic. This contradiction signifies the self-esteem of the aristocracy and at the same time indicates its estimation among the people. Exclusivity, which arose from the obscurantism that was inclined to rest comfortably on the laurels of one’s ancestors and to skim off the cream of history as a traditionally born leader, the self-willed isolation, detached the aristocracy from the people and killed its instinct. The result: a great yesterday, a petty today and no tomorrow at all.

The people have become mature. The leaders and saviours have emerged from the people. Adolf Hitler arose from the soul of the people. You, aristocratic gentlemen, may bristle because that insults your vanity, because each of you in your opinion must be the leader, you might agitate and stir up trouble, as you still do today, but the aristocracy is dead, because you have killed it by your behaviour, your attitude, your selfishness. Besides, your inveighing too will cease. The aristocracy is dead and already there arises from the people a new aristocracy filled with the sacred duty of building up Germany. New names have once again a strong resonance and inner significance. A new elite has a new calling among the people. A new aristocracy rises again as the bearers of the idealistic worldview in which one’s own advantage cannot mean anything compared to the duty to serve the people, the country, the state and its representatives to the utmost. One who stands at the very front is the aristocrat!

The aristocracy is dead, long live the aristocracy! We thank our Führer that, when the old failed, he gave and trained for the people his new aristocracy, for which it is no longer a matter of names and external appearances but which simply exists and fights.

* * *

Dr. Achim von Arnim [1881–1940],

Professor of Military Science, Technical University of Berlin,

SA Oberführer[6]

The German aristocracy belongs to Adolf Hitler

One can grow to be a National Socialist, but the disposition must indeed be inborn. Forms that are once internally imprinted begin to develop no matter how hard one tries to disperse them. As the son of a Prussian officer and a mother from Alsace, a certain dichotomy of temperament was allotted to me. Along with Prussian sobriety I possess enough imaginativeness and sprightliness to have a quick sympathetic understanding of new things.

My parents lived in various garrisons of the Imperial Guard and, like every officer’s son, I attended the high school. It was the nineties of the last century, in which the memory of the victorious wars of 1866[7] and 1870/1[8] was still alive. It seems to me that the German nation was brought too quickly to life through the success of Bismarckian politics. Wealth and splendour had fallen suddenly into the lap of our people, who had hitherto been modest and sober. It thereby lost its spiritual equanimity. The German, distinguished by his depth and his rich world of feeling, developed in the last 20 years of the century into a man of rational understanding and a materialist. The school offered no counterpoise. The teachers were not aware that they had to conserve in the best sense the tradition of German Humanism and the idealistic tendency of German Classicism. Of course there were among them men rich in ideas and pedagogically skilled, whose instruction I still remember with gladness.

In general, however, a too copious information was transmitted to us and, specifically, without any political influence. I can especially not forget that, during my schooldays, no explanation of the political development of our nation was given to us. We learnt nothing about social and economic development, nothing about the significance of the battles that began with the French Revolution, of the opposition to Liberalism at the beginning of the previous century, of the dissemination of the mercantile spirit and of capitalism. To be sure, one occasionally heard frightful things about the Social Democrats[9] — at the elections one was frightened by the increasing percentages of their mandate. I went to school for many years in Spandau, there there was a strong population of workers with whom there was no connection at all. We high school students met only with our peers, and I always had the feeling that the boys of the public school were particularly rough and uncouth.

But a slightly better insight was then given by my entry into the army. In just a few months — and that is too short a time, the prospective cadet was, when he left school, consigned to the squads. I served in the First Regiment of the Imperial Guard and this had the best reserve troop from all of Prussia, tall blond men from the healthiest families of our nation. I had imagined the time in the ‘barrack room’ as something very unpleasant, as being in the company of a number of coarse, immature and boorish fellows and still remember my surprise that this image did not correspond at all to the reality. On the contrary, the young soldiers with whom one lived — 20 in a room — were actually, in their moral constitution and habits, cleaner and more modest than the higher society with which I later socialised. It was also not difficult to find the right tone in communication, one just could not act like something better — and indeed one was not, for, as a scholar, one was not so familiar with the practical matters of life as the young soldiers. I then had similar good experiences as a young corporal. This first period as a soldier, which lasted only a short time, was a period of learning, perhaps not for the prospective officer but for the growing man. Nowadays, the young men, and even the women, come into contact more often, through the German Youth,[10] the German Girls’ League,[11] the Hitler Youth and community service, with all strata of the working people. Thereby they develop a stable judgement and learn to have the necessary consideration in dealings with men of different backgrounds.

The pre-war officer corps, which I entered a year and a half later, did not at all correspond to the caricature that was made of it at that time in the Liberal satirical papers and in the bourgeois world. There was alive, especially still in the older generations, the sincerity and loyalty of the older generation that had fought the wars for unification. Fastidiousness in service, conscientiousness, the consciousness that one had to set an example through personal commitment, the feeling of responsibility for subordinates and even one of the necessity of a comradely relationship with them was totally alive.

But I became aware early of one thing, that this officer corps, not only in my regiment but everywhere else, represented an exceptional class that was, to a certain extent, separated by a glass wall from the life, activity and feeling of the rest of the nation. In it there lived on a portion of the eighteenth century. The officer was obligated to the warlord and felt himself bound only to him, and, because reverence for the monarchy and devotion to its sustenance was his political morality, the officer believed that he did not need to worry about other political questions. It was the time when Germany stood at its absolute peak economically. Everywhere great fortunes arose. One did not know of any unemployment. Every worker could hope that he could, through his own industriousness and economising, conduct his children to a higher profession. There existed therefore the total possibility that the upper strata would continually supplement itself from the people.

In reality, however, that took place only to a small degree. The institution of the ‘one-year service’[12] formed an absolute class border. One who had taken this test — he did not even have to have served for a year — belonged to the cultivated and higher strata, everybody else was a subaltern and belonged to the people. If we look back retrospectively at this period with Liberal eyes, we must ask ourselves how it was possible that Social Democracy rose so powerfully in a period when everybody had a good income. From a materialistic standpoint there is no answer to that. But from the idealistic standpoint, it is a question of the longing of a great part of our people who had reached adulthood in the course of the century for a national community, for a spiritual rapprochement with the so-called higher strata. Not all of us overlooked the role of the Jews in that period. But one who spoke of a Jewish danger was laughed at as a fantasist. If as a young man I had been invited to become a Freemason I would have accepted the invitation in the belief that one may find a rich spiritual life in this order. But this spiritual life and this understanding were lacking precisely in those classes with whom we officers socialised. The bureaucrats, owners of large landed properties and other highly placed persons with whom we socialised were duty-conscious and industrious but matter-of-fact men careful of their careers. Only seldom did one find intellectually open-minded and artistically inspired personalities. The attitude to the people was benevolent but derived from a feeling of an obvious inborn social superiority. Manual work was considered as inferior compared to intellectual work, which we supposedly performed.

We would have been able to obtain stronger impressions of the life and feeling of the people if there had existed the possibility of being instructed on worldview, political and social questions. But who would give this instruction? We officers were considered educators of the youth entrusted to us and doubtless did our best. Indeed, in the education for the soldier’s profession and war, performance was at an optimum. But the worldview education which we had to impart through our instruction had to be a failure because we ourselves lacked the necessary knowledge. It was indeed so, as the Führer said: before the period of service nobody cared about the young man, and after his service period neither. One knew hardly anything about the Marxist organisations and the trade unions. Their intensive propaganda work was hidden from us.

Then there came the war and very close contact with all strata of the population on the front in cohabitation, for weeks, in damp trenches and in basic accommodation. I definitely believe that not only I but all the older officers of the front felt that we had a close sense of bonding with comrades of all service grades and that in moments of danger it did not matter if one wore the epaulets of an officer or a corporal’s cross or a lance-corporal’s button. To all those who felt in this way the Revolution,[13] with the sudden revolt of the soldiers against the officers, was then a bitter disappointment. One recognised soon that it was not the good elements of our squad that became mutineers and deserters but young elements that had been poisoned in their hometowns and were inexperienced, who had to suffer the bitter deprivations of the wartime in the last years and had perceived the affliction in their homeland. With no defenses, they were exposed to the influence of Red propaganda. The revolution period separated the men. The major part of the officer corps and the members of the former higher classes were starkly against the revolution and its manifestations. These men saw only the ugly external images and wished to hide from the knowledge that here a people who had been misguided strove for a better social status through a semi-conscious longing. They should not at that time have separated themselves in this way from the people but followed the path that Adolf Hitler did, attempting from the start to give the people what it strove for and to combat what was pernicious.

While most of the officers, also demoralised, had to take up the difficult battle for survival and persevered in their rejection of the social questions, I remained for a while vacillating and searching. Finally ,thrown in the country, I found myself one day, in 1925, a District Leader of the Stahlhelm. One had heard something of Adolf Hitler and his movement in Munich only through the Putsch. It is astonishing and hardly believable today how little one knew, here in the country in the east, of the National Socialists. I saw my duty as saving the small town workers, and especially the rural workers, in my district, filled with estates and small cities, from Marxism. These were strata of the population into which the Red organisation had not yet penetrated fully. The Stahlhelm had inscribed on its shield the spirit of the soldiers of the front, that is, the community of the comrades in the trenches. With lorries and bands we drove through the country, held speeches in every village — whereby there was also a ‘beer movement’ — and founded everywhere local groups of the Stahlhelm. Even the landowners and — what was not always very easy — the agricultural bureaucrats were won over to our ideas and, in this way, we succeeded in the beginning in achieving something that was of course not even closely as well-thought out, but similarly felt, as what Adolf Hitler strove for.

If later, after a seven-year activity as Stahlhelm leader, I turned my back on the organisation, I must give the reasons for that without wishing to hurt the former comrades of the Stahlhelm who had been won over to our cause. There had entered a certain torpidity in my feelings on account of the faltering politics of the federal leadership, which had to wriggle through with difficulty between a more conservative and military orientation and a social orientation, and, in the meantime, National Socialism had arisen among us. In all villages and small towns there were Brown departments, and the Stahlhelm people were the proof that these were really more active, that, in neighbouring Berlin, hard battles for rule were fought in the Red quarters, that a strong atmosphere of intellectual tension emanated from the Hitler movement and that a good and clearly orientated press helped the movement to move forward. The Stahlhelm found itself at a dead end since it did not want to fight in a parliamentary way and did not have the power to rise to power with arms. Finally the social question also seemed to me to fade somewhat. The workers won over by me and bound to me for a long time expressed many doubts about the goals of the Stahlhelm. They seemed to them as if they were all about a movement in favour of the old ruling classes.

So finally there was a certain discord because I freely acknowledged my view which favoured National Socialism, and that led to my exit from the organisation, which made some sensation at that time, when the SA was prohibited. There followed a period of bitter hostilities on the part of former friends and comrades. But I can only say that I have not regretted my step one day and have seen during my career in the SA so much that was elevating and invigorating that it seems to me a good fortune to be able to continue to experience the present times. If the Prussian aristocracy for the most part showed at first little understanding of the way that I took that must be explained by its strong adherence to the Prussian tradition. The feeling of rulership cultivated through the generations, especially of the rural aristocracy, perhaps made it difficult to find a way to our people the way we in the SA did. But I think that the conviction must seize some earlier, others later, but hopefully all one day, that another way than the one that our Führer has taken is not passable for our German people. If we wish to come through victoriously in the tremendous fight for survival that we must still undertake in order to sustain our nation, given our unfortunate international situation and our unequal mixture of races, it will happen only if all the strata of our sorely tested people march together with complete trust, and that is possible only in National Socialism.

Berlin, 15 January ,1934.

* * *

Count Wolf-Heinrich von Helldorf [1896–1944]

Police Commissioner of Potsdam

Gruppenführer[14]

The Aristocracy and National Socialism

The entire public and private life in Germany today is influenced in a decisive manner by National Socialism. Everything that was ready and willing to cooperate in the building up of the nation is gathered under the sign of the swastika. We have to regretfully acknowledge that the bearers of old aristocratic names are involved to an extremely small degree in authoritative positions in this work of construction within the movement and in the state. This fact is especially surprising considering that the NSDAP has declared not once but many times that it would reach out its hand for the purpose of cooperative work to anybody who would place himself at its disposal unconditionally. The reasons that led to this superior aloofness of the aristocracy should be investigated here, and I think that we will reach a conclusion most easily if we review once again the political development in our nation during and after the war and, in this way, examine the attitude of the aristocracy to the National Socialist idea.

The ruling and state-governing classes in the Bismarckian empire were the officer and bureaucratic classes. Aristocratic officers and bureaucrats stood here in a preferred and leading position. When Germany decided in 1914 on the fateful four-year long armed conflict and the Prussian German army marched in the glow of its centuries-old military culture to the defence of the homeland and carried the war to hostile countries, the Prussian German aristocracy, following the old tradition, occupied a leading position within this national army. This army fought and won in the battlefields of the whole world and, at its head, fought and bled the German aristocracy. Once again, before the great collapse of the monarchy and the aristocracy, those fit for military service from the aristocratic families were conscious of their proudest privilege sanctified by tradition: they died a heroic death in a natural fulfilment of duty.

If, later, people repeatedly and rightly pointed to the total inaction of individual families and members of the German aristocracy, one must, on the other hand, rightly acknowledge and ascertain that no class in Germany took part in this four-year long conflict with such an enormous sacrifice of blood and death as the aristocracy and declare that the best of us have fallen.

In the political leadership of the German nation in the pre-war and war years the aristocracy did not live up to its duties. The aristocracy and the people no longer understood each other. The aristocracy no longer spoke the language of the people and thus it failed, detached and separated from the people, both in internal and in external politics. In the foreign policy of that time, which was especially strongly influenced by the aristocracy and unfortunately also by Jewry, there was no politician or statesman who rose even a little above the average level. After the enormous blood sacrifice of the international conflict, the aristocracy seemed to have exhausted its last strength, which had been kindled in its old families even during the war. Only a few of us confronted the mutineers of 1918 vigorously. The throne and altar were abandoned, the Kaiser empire crumbled, and with it the aristocracy.

The history of the revolution is at the same time the history of the collapse and disintegration of the German aristocracy. The heroes of yesterday, the pillars of support of throne and altar, soon became spineless servants of a state that could be created only after the strongest supports of this state had bowed down before traitors and mutineers. When the red flags of the revolt fluttered and the mobs raged in the streets, they of course complained and protested but they forgot to fight, and found the required justifications for everything that they did and were not sparing in declarations dripping with patriotism. The majority of the aristocracy accepted the situation as it was. The majority of the aristocracy came to terms with the Weimar Republic. For the majority of the aristocracy and especially for the older generation it was still only a matter of a lesser evil that one had to put up with, in order not to lose everything. On major patriotic festival days the uniforms of the old regiment were brought out now and then to keep up tradition, one gave pleasant speeches at war associations and expressed the hope that God would indeed grant us better times once again. None of us wanted battle itself. Indeed it was much more convenient to be promised peace and order from the Weimar Republic and, for that reason, to change one’s attitude a little. It is worth mentioning that, in this period, Jewish families with and without noble surnames played the principal role in the aristocracy. Everything pressed round the golden calf and one was able to note, for example, with trembling fear, in Berlin society in the years 1924–1925, that degenerate aristocrats were tolerated guests in rich Jewish families, that all the so-called good houses were open to a notorious criminal like, for example, the Jewish state secretary Weismann.[15] In general, one who disseminated propaganda for the ‘Realpolitik’ of the ‘statesman’ Gustav Stresemann,[16] eulogising with many fine speeches in cities and the state, was valued as a specially intelligent aristocratic comrade. One put up with everything, even the worst phenomena of the time, and even the German aristocratic association, as a socio-economic organisation of the aristocracy, was in no way directive but satisfied itself merely with transferring external forms of the past to the republican present.

The aristocracy organised itself after 1918 chiefly in the German National People’s Party[17] and the Stahlhelm and, in the battle years, both groups virtuously did everything that was in their power to make life bitter for us few National Socialists from the aristocracy and to mock and denigrate us and our battle for the German nation. The first great election assembly will always remain in my mind in which I was to appear in Halle for the first time in my life, in 1924, as a speaker for the National Socialist Freedom Party. In front of an overflowing assembly that absorbed with enthusiasm the programmatic representation of the National Socialist battle goals there spoke, after me, as a respondent, the party secretary of the German National People’s Party, and also the Stahlhelm leader in Halle, Senior Lieutenant Düsterberg,[18] and a war-blinded Communist. While the performances of the latter were completely moderate, Mr. Düsterberg, who, as is well-known, is Jewish, used the opportunity to oppose the young freedom movement in the harshest way. Even at that time I was amazed by the blind hatred that filled this man but did not know that the formerly active officer of the military staff was Jewish.

Therewith I come to the saddest chapter in the history of the German aristocracy of the present. We stand before the shocking fact that that part of the population that, according to blood, race and a centuries-long tradition, was called and, as we believe, is still called to present to its people statesmen and soldierly fighters in the great freedom fight that the National Socialist movement had conducted for 14 years stood aside without any understanding of the great changes that had occurred in the German national soul, retreated into a completely misunderstood aristocracy and, often not without justification, invited upon itself the hatred and the contempt of large masses of the people.

The aristocracy took part only to an extremely small degree in the powerful battle within the country under the leadership of Adolf Hitler. It must indeed be said clearly that the aristocracy, and especially the post-war generation, succumbed frightfully quickly to the influences of liberalism and democracy. The smaller part of it encapsulated itself in the seclusion of conservative or nationalist clubs and in professional associations conducted in a parliamentary political manner. The German national Stahlhelm leaders in the aristocracy laughed at us ‘reckless and immature young people’ when we stated clearly in public that we love our German people and hate its enemies. They thought it was not ‘chic’ to get into close discussions in national assemblies with KPD[19] and Reichsbanner[20] people. If we fought in national assemblies and in the street with fellow Germans filled with hatred they spoke of us as hooligan elements that had unfortunately not learnt to behave according to their ‘class’.

Even if one accepts and understands — for the reasons that I have presented at the beginning of this essay — that the aristocracy in 1918 did not oppose any decisive resistance to Ebert,[21] Scheidemann[22] and Noske[23] with their mutineering hordes, the meagre participation of the aristocracy in the political battle of Adolf Hitler will always remain incomprehensible. It cannot be explained or excused by anything that a class that presented to the people through the centuries leaders, and not the worst, refused adherence to the man who set about, after the collapse of the old leadership in Germany, to educate new young leaders, who however demanded even from these young leaders that they had to prove their suitability and set for each of us strong endurance tests before the title ‘leader’ was granted to us.

After the aristocracy had been unable through its own strength to change the fate of its people, we must, in retrospect, regretfully state that, even in the last part of the development of German history, which stood under the sign of victorious National Socialism, it did not understand to put a stop to its inner disintegration and cooperate in the new formation of affairs with all its forces. This failure of a valuable and, insofar as it is a question of the landed aristocracy, racially superior and healthy section of the population, is so much more regretful in that the National Socialist movement built and conducted on aristocratic principles had to correspond completely to the inner constitution of the aristocracy. Just as among the ancient Germans the best person in terms of family, clan and tribe was the heir-apparent and became the leader, so also in the National Socialist movement the best person in terms of performance and blood is the leader. People may say of the aristocracy that it is in the process of committing serious mistakes that can never be remedied, both to itself and to coming generations. There is no doubt there is forming in National Socialism a new ruling class of the German nation. If the aristocracy stands aside from this great aristocratic national movement, destiny will pass over it and then it would be better if it decided to discard its aristocratic titles which have becomes worthless.

The aristocracy stands at the turning point of its history. It is up to it to demonstrate, through its conduct in relation to National Socialism, that race and blood can overcome darkness and class conflict. If the aristocratic principle of the NSDAP according to which only one who fulfills special duties may claim special rights for himself penetrates the aristocracy of today, and if the aristocracy incorporates itself wholly and unconditionally in the great national community of Adolf Hitler, then the possibility will be offered to it even today of recovering its position in the German nation which has been strongly shaken by the events of the last 14 years. And then the proudest privilege of the aristocracy will remain that of offering its sons to the fatherland.

[1] Stephan Malinowski, Vom König zum Führer. Sozialer Niedergang und politische Radikalisierung im deutschen Adel zwischen Kaiserreich und NS-Staat, Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2003.

[2] See, for example, Elke Fröhlich, Die Tagebücher von Joseph Goebbels, I, iii, p.470.

[3] The rank of an SS Standartenführer was equivalent to that of a colonel.

[4] The Almanach de Gotha was a standard directory of European nobility published from 1763 to 1944.

[5] The Stahlhelm was a league of ex-servicemen of the First World War that acted as a paramilitary force of the monarchist German National People’s Party (DNVP) from 1918 to 1935.

[6] A rank between colonel and brigadier-general.

[7] The Austro-Prussian war fought between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia.

[8] The Franco-Prussian war fought between the French Second Empire and the North German Confederation led by Prussia.

[9] The Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD) was established in 1863 and Friedrich Ebert of the SPD became the first president of the Weimar Republic (1918-1933).

[10] The ‘Deutsches Jungvolk’ was the junior division of the ‘Hitler Jugend’, for boys aged 10 to 14.

[11] The ‘Bund Deutscher Mädel’ was the female youth organisation of the National Socialist party.

[12] A reference to the ‘Einjährig-Freiwillger’ volunteers of the Prussian army who, after a year’s service as volunteers, were made reserve officers.

[13] The German Revolution, or November Revolution, of 1918 was a mutiny of German sailors in Wilhelmshaven and Kiel that led to prolonged civil unrest in Germany that ended with the establishment of the parliamentary constitution of the Weimar Republic in August 1919.

[14] Section Commander.

[15] Robert Weismann (1869-1942) was state secretary for Prussia during the Weimar Republic.

[16] Gustav Stresemann (1878-1929) was a politician of the Weimar Republic who served as Foreign Minister and, briefly, Chancellor.

[17] The Deutschnationale Volkspartei (DNVP) was a nationalist and monarchist conservative party of the Weimar period which rejected the Weimar Constitution and the Treaty of Versailles.

[18] Theodor Duesterberg (1875-1950) was a staunchly anti-Semitic leader of the Stahlhelm who was discovered in 1932 to have partly Jewish ancestry. He consequently resigned from the Stahlhelm in 1933.

[19] The Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, founded by Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, was a major political party of the Weimar Republic. It was banned in West Germany in 1956.

[20] The Reichsbanner was an organisation of the Weimar Republic devoted to upholding parliamentary democracy in Germany.

[21] Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925) was a member of the SPD and first president of the Weimar Republic.

[22] Philipp Scheidemann (1865-1939) was a member of the SPD who served as Chancellor of the Weimar Republic between February and June 1919.

[23] Gustav Noske (1868-1946), of the SPD, was Minister of Defence of the Weimar Republic between 1919 and 1920.