Mark Leibler in the early 1990s

Mark Leibler in the early 1990s

Go to Part 1.

Go to Part 2.

Having Their Cake and Eating It Too – The Dual Citizenship Campaign

By the mid-1980s Mark Leibler had established the Zionist Federation of Australia as “a political lobbying powerhouse.” The organization was centrally involving in ensuring 7,000 Australian Jews who had made Aliyah to Israel retained their Australian citizenship. Under the Citizenship Act, Australians could not become citizens of another country without giving up their Australian citizenship, as Rupert Murdoch had done to become an American citizen. Under Israel’s Law of Return, Jews who settled in Israel automatically became Israeli citizens – meaning they had implicitly renounced their Australian citizenship. This was not enforced by Australian authorities prior to 1986. That year, however, the Labor government introduced legislation to amend the Citizenship Act to clarify the prohibition on dual citizenship. The bill prompted Immigration Department officials to rule that those who had settled In Israel before 1981 and become Israeli citizens would have their Australian citizenship revoked and passports cancelled. So too would Australian Jews who had arrived after 1981 and been granted permanent residency by Israel.

Among Australian Jews there was outrage and panic, and the “ZFA was inundated with demands for help. Contrary to what Australian immigration officials had always told them, not only would adult Australians in Israel lose their citizenship, but so too would their children who had been born in Israel.”[1] These Jews, noted Gawenda, who Leibler and the ZFA regarded as a Zionist success story, wanted to have their cake and eat it too. This situation might have “raised the old charge of dual loyalties, a long-standing anti-Semitic trope in which Jews are a sort of fifth column, with greater loyalty to their fellow Jews than to the country in which they live and are citizens. Here were Jews committed to Israel, living and raising children there, even serving in the Israeli army, and yet determined to hang on to their Australian citizenship.”[2]

Leibler coordinated an intensive lobbying campaign to have Jews granted a special exemption to the dual citizenship laws. A “sense of urgency” gripped Leibler during this campaign; he “was a man possessed, furiously working on this issue, and sometimes furious when he didn’t get his way, as, for instance, when an Immigration Department official refused to see the logic and force of the case Leibler was putting to him.”[3] In his notes, Leibler recalled that “The conversation was very heated and I was quite abusive.” Leibler was adamant “this problem would have to be resolved even if it meant I had to go and see the Prime Minister for the second time that day.” Leibler had met with Bob Hawke earlier that day as part of a delegation organized by the Executive Council of Australian Jewry.

Leibler insisted on seeing [then immigration minister] Chris Hurford who “interrupted a lengthy meeting with a rather important lobby to see me.”[4] Hurford caved in to Leibler’s demands/threats and, in April 1986, with Opposition support, announced amendments to the government’s proposed citizenship legislation that restored the citizenship of all the Australian Jews living in Israel. Leibler’s victory was complete.[5] In 2002, the Howard government made dual citizenship legal, “in recognition of Australia’s diversity and multiculturalism.”[6]

Courting Paul Keating and John Howard

When Paul Keating successfully challenged Prime Minister Hawke for the leadership of the Labor Party in 1991, there was consternation among the ranks of Jewish activist organizations. At the time “there was a wave of grief through some sections of the Jewish community at Hawke’s departure,” and Jewish leaders “effusively praised the former prime minister.” Bob Hawke was “particularly close to the Jewish community” and, in particular, to influential Jews like Isi Leibler, multicultural activist Walter Lippmann, and wealthy businessmen like Eddie Kornhauser and Peter Abeles. All “had direct access to the prime minister.”[7] Bronwyn Hinz noted the far-reaching social policy implications of Walter Lippmann’s close association with Hawke:

In the 1980s, the ECCV [Ethnic Communities Council of Victoria] worked closely with Prime Minister Bob Hawke, a personal friend of ECCV founding Chairperson Walter Lippmann. As the representative of Melbourne’s most ethnically diverse electorate, Hawke was especially cognizant of the value of close connections with the peak council, its activists and member groups, accepting most invitations to their functions, and providing Lippmann and other ECCV activists with direct access to his office. In the first year of the Hawke government, the ECCV’s lobbying culminated in the reduction of citizenship waiting period to two years, the replacement of the term alien with “non‐citizen” in the 1983 Migration Act, and an increase of the refugee intake.[8]

Leslie Caplan, president of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, lamented Hawke’s political demise, describing him as a man of “extraordinary ability, intellect, compassion and charm who had a special relationship with the Jewish community.” Mark Leibler, then president of the ZFA, likewise extolled Hawke as “a giant among men, a great prime minister, a close friend of the Jewish people and a constant supporter of the security and integrity of Israel.”[9] While making this public statement, he had been busy behind the scenes courting Hawke’s successor. After Paul Keating’s first unsuccessful challenge to Hawke, Leibler had sent him the following handwritten letter:

Dear Paul,

Strange isn’t it that the loser on the votes emerges looking very much the winner in all other respects, But then perhaps not surprising at all!

Congratulations on the performance. I look forward in anticipation to the Second Act – its final and successful completion.

Wish you much luck

With best wishes

One of your many admirers

Mark

Keating wrote back, thanking Leibler for his note, and for his “words of encouragement and support.”[10] Sniffing the changing political winds, Leibler carefully positioned himself as Keating’s Court Jew. Keating’s defeat of Hawke left the field open for Mark Leibler to assume a position hitherto occupied by other Jewish leaders like his brother Isi, “Almost all of whom had developed a relationship with Hawke, whom they considered the community’s and Israel’s greatest friend in the Labor government.” Given Isi’s particularly close relationship to Hawke, and the latter’s defeat “was particularly hard for Isi to handle” and “with Hawke gone his contacts in and access to the government were severely diminished. He had no real relationship with Keating, and developing one would be difficult, given his well-known closeness to Hawke. His brother Mark was really the only Jewish leader with a significant relationship with the new prime minister.”[11]

Former Prime Minister Paul Keating in the United States in 1993

Former Prime Minister Paul Keating in the United States in 1993

In an article in the Australian Jewish News from the time of Keating’s successful challenge to Hawke, Leibler declared that he was confident that “In light of my contacts with Paul Keating over many years … there is no reason to believe that there will be any shifts in government policy which would be adverse to the interests and concerns of the Australian Jewish community.”[12] This signaled to other Jewish leaders, including his brother, that he was uniquely placed “to make the case to Keating on any issue that concerned the Jewish community.”[13]

One such issue emerged early in Keating’s tenure as Prime Minister. There was widespread concern, even alarm, among organized Jewry regarding Keating’s foreign minister Gareth Evans’ stance towards the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians. Gawenda notes that “Many Jews had been alarmed by the Scud missiles that Saddam Hussein had rained down on Israel during the Gulf War [in 1991] and by the sight of Israelis wearing gas masks out of fear that the missiles would be armed with poison gas.” The PLO had organized demonstrations in support of Saddam Hussein, and many Western nations had, as a result, cut contact with the PLO.

A year after the end of war, Australian foreign minister Gareth Evans decided the Australian government should restore contact with the PLO. Keating, who had little personal interest in the conflict between the Israel and the Palestinians, publicly supported this decision. A month after the announcement, Evans visited a Palestinian refugee camp in the West Bank and criticized the expansion of illegal settlements by the Israelis. Evans even expressed support for United Nations Resolution 194, passed at the end of the 1948 war, which called for the right of return of Palestinians who had fled or been forced out of their homes (i.e., ethnically cleansed) by the war. Mark Leibler was “enraged” at Evans’ stance, which, interpreted one way, could result in the return of all Palestinians and their descendants which “would have meant the end of Israel as a Jewish state.”[14] Hitherto, both major political parties in Australia had followed the United States position on the resolution: that it only allowed for a token number of Palestinians to return in the event of a peace settlements, thus preserving the Jewish demographic supermajority in Israel.

Leibler met Evans on his return to Australia and “according to people with knowledge of the meeting, Leibler and Evans exchanged views in a very robust fashion. Insults were exchanged.”[15] Jewish Labor MPs joined Leibler in attacking Evans, with former Whitlam and Hawke government minister Barry Cohen telling The Australian the foreign minister’s stance risked the loss of political donations from wealthy Jews, and that Australian Jewry had always been a source of ideological and financial support for the ALP, noting, “That [support] will be weakened whenever a government appears to be antagonistic towards the state of Israel.”[16] The bad optics of Cohen’s open threats troubled some Jews at the time, including Leibler. While fiercely critical of Evans, Leibler was adamant “Jewish leaders should not make any [public] threats about donations to political parties or threaten to urge the Jewish community to vote against the government because of its policies in the Middle East.”[17]

Leibler’s next gambit was to invite Keating to speak at the ZFA’s biennial conference in 1992. In his speech, while not repudiating Evans’ views, Keating focused on “the ALP’s historic commitment to Israel and emphasized his government’s unwavering commitment to Israel’s security.”[18] Shortly after Keating’s speech, Evans’ stance on Israel and the Palestinians suddenly became irrelevant. Yitzhak Rabin led the Israeli Labor Party to victory in the 1992 general election. Many senior Keating government figures had ties to the Israel’s Labor Party and personally knew Rabin and members of his government like Shimon Peres. The result was that “criticism of Israel’s settlement policies was significantly toned down.” This was particularly so after the Oslo Accords between Rabin and Yasser Arafat were signed on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993.

Rabin was assassinated in November 1995 by Yigal Amir, a radical Zionist opposed to the Oslo process. Keating attended Rabin’s funeral and, three months later, was defeated in a landslide by John Howard at the 1996 election. Despite Keating’s defeat, Leibler continued to cultivate a close relationship with Keating. Meanwhile, Zionist activists in the United States and Australia were secretly happy to see Rabin disappear from the scene. As Gawenda notes:

Shortly after he was elected, Rabin told American Jewish leaders, including AIPAC officials, that they needed to modify their lobbying for Israel. That was code for his view that their lobbying was counter-productive and that Israel was perfectly capable of developing its own relations with Congress and the President without their interventions. Rabin’s message was a stunning repudiation of the work of AIPAC. An Israeli prime minister was telling the most influential Jewish lobby group – perhaps the most influential lobby group in Washington – to back off, that he did not need their help.[19]

Following a meeting with Rabin in Israel, Isi Leibler had reported back to the Australian Jewish media that Rabin had asked him to inform Jewish organizations in Australia (including the ZFA) that they should “drop the quasi-diplomatic role they have adopted in Australian-Jewish affairs of state.”[20] Instead, government-to-government relations should be left to the Israeli embassy in Canberra, and Jewish organizations should focus on trade with Israel and fighting anti-Semitism. For Mark Leibler, Rabin’s remarks (as reported by his brother) “were a repudiation of his life’s work, of the years he had spent building up his political contacts in Canberra so that he could put the best case for Israel to whatever government was in power.”[21]

Paul Keating was ideologically predisposed to embrace the agendas of organized Jewry in Australia. A Cultural Marxist and economic neoliberal, Keating harbored with a deep-seated animus toward the traditional Australian nation, and was a strong proponent of Australia’s economic and demographic integration into Asia. In an interview for The Powerbroker, Keating explained that he “believed in a cosmopolitan Australia” and was bemused why some “Jewish people ever vote for someone like [former Prime Minister John] Howard.” This was especially so given Howard’s putative support for some of the positions of Pauline Hanson in the mid-1990s – part of his successful attempt to steal votes from her then politically-ascendant party.[22]

Howard’s faux White Nationalism was utterly cynical and strategic, and he later oversaw the biggest expansion in non-White immigration in Australian history. His government created the Section 457 Visa for temporary workers – a visa program designed to be uncapped and totally driven by the putative needs of the Australian labor market. The 457 Visa led to a massive increase in cheap non-White labor brought into the country. It was also the Howard government that, from the early 2000s, encouraged overseas students to apply for permanent residence after completing their courses in Australia. The inevitable result was an explosion in overseas student enrolments, and by 2017–18 overseas students had become the largest contributor to Australia’s very high level of Net Overseas Migration (NOM) which numbered 271,700 people in 2019.

Howard also presided over Australia’s shameful involvement in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and probably even exceeded Bob Hawke in his fawning philo-Semitism and subservience to Israel. Dan Goldberg, the editor of the National Jewish News, observed in 2006 that:

From his first encounter with Jews, as a nineteen-year-old at the Sydney law firm of Myer Rosenblum, Howard has, especially over the last decade, cemented his alliance with the Jews, and has arguably eclipsed even the great Bob Hawke as the most pro-Israel prime minister in Australian history. Most of his empathy is a function of his foreign policy, pivoted on the US alliance, which translates in the Middle East arena to unequivocal support for Israel, regardless of which prime minister is in power in Jerusalem. Of course, Australia’s role in the war in Iraq was no doubt seen by most Australian Jews as yet another significant milestone in the long history of relations between Canberra and Jerusalem.

It is no coincidence therefore that Howard has received major awards from three Jewish community organisations in the last couple of years. It is also no coincidence that he speaks regularly to Jewish audiences, and that he is closely allied with a clutch of Jewish powerbrokers. … Understandably, most Jews were in favour of eliminating Saddam Hussein and his regime if only because he bankrolled families of Palestinian suicide bombers to the tune of US$25,000 each, not to mention the fact that it would neutralise the threat to Israel’s eastern flank. The fact that Australian SAS forces took out Saddam’s stockpile of Scuds aimed at Tel Aviv in the early hours of the war only augmented the bond between Canberra and Jerusalem.[23]

Despite Howard’s cynical willingness to appeal (like Donald Trump) to implicit White interests to win elections, Leibler retains “a huge amount of respect and affection for Howard, who was unshakeable in his support for the Jewish community and Israel.”[27] For Gawenda, Howard’s government was “probably the most pro-Israel government in a long time.”[28] Howard himself spoke of his “long association with the Jewish community of Australia of which I am unapologetically proud.”[29]

In 2000, Prime Minister John Howard asked Mark Leibler to become a director of the newly established body called Reconciliation Australia to promote the welfare of Australia’s Aborigines. Leibler accepted, and speaking on behalf of Australian Jews, claimed: “We’ve suffered 2,000 years of persecution and we understand what it is to be the underdog and to suffer from disadvantage.”

Former Prime Minister John Howard (second from right): leader of “probably the most pro-Israel government in a long time.”

Former Prime Minister John Howard (second from right): leader of “probably the most pro-Israel government in a long time.”

Seemingly oblivious of all this, Keating claims to be bewildered why “the Jewish community here could ever vote for the Coalition whilst Howard-type views abounded. … So I got a bit short with [the Jewish community], still am I suppose. I tell them that ‘the one party that would actually stick with you through thick and thin on the question of identity, your identity, is the Labor Party.” Moreover, it was Labor governments, he insisted, “who helped you make all the money.”[30]

It has been a longstanding strategy of wealthy Jewish businessmen and activists to cultivate relationships with prime ministers on both sides of politics: in the words of Mark Leibler: “John Howard certainly, and Bob Hawke of course, and yes, Paul Keating, and so too Malcolm Turnbull.”[31] Wealthy Jewish businessmen and Jewish activists often coordinate their lobbying efforts. Leibler notes how he could reliably “call one of these business people who I knew had a close relationship with politicians on both sides of politics. I would ring up and explain that there was a problem and that they needed to sit down with the PM and explain the problem. They would always be very helpful doing that.” While these Jewish tycoons often weren’t comfortable issuing public statements, they “had the sort of relationships with prime ministers and foreign ministers too, that allowed them to intervene.”[32] When asked whether this level of access was a unique situation for a Jewish community of such a small size (Australia’s 120,000 Jews make up less than half of one percent of the Australian population), Leibler’s response was unambiguous: “The answer is, yes.”[33]

Leibler’s Campaign against Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party and the Extension of the Racial Vilification Act

Mark Leibler played a key role in the Jewish attack on Pauline Hanson and her “exclusionary form of nationalism” in the 1990s. Andrew Markus notes how Hanson’s “campaign evoked widespread condemnation within the Jewish community and calls for mobilisation to challenge the growing influence of her movement. Concern was at its peak following the success of One Nation in the 1998 Queensland election, which opened the prospect of a One Nation dominated Senate.”[34] In response to Hanson, more than thirty Jewish organizations signed a statement denouncing “racism,” and supporting the formation of a new Jewish activist front group called “People for Racial Equality.” Jewish organizations that vehemently opposed Hanson included the Executive Council of Australian Jewry and the Australia/Israel and Jewish Affairs Council led by its chairman Mark Leibler. The “People for Racial Equality” campaign aggressively targeted political parties and politicians, demanding they put One Nation last on their “how to vote cards,” as well as individual voters, urging them all to put One Nation last under Australia’s system of preferential voting.

In an effort to shame and intimidate Hanson’s supporters, the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation Commission doxed 2000 people associated with the One Nation Party. The list was published with Mark Leibler’s consent in AIJAC’s Australia/Israel Review under the headline “Gotcha! One Nation’s Secret Membership List.”[35] In keeping with the tactics of organized Jewry throughout the Western world, the attempt by Hanson and her supporters to ensure that White Australians retained demographic, political and cultural control of Australia was represented as racist, immoral, and indicative of psychiatric disorder. Central to the Jewish response to One Nation, notes Markus, “was repugnance at public expressions of bigotry and a sense that while the focus of the Hanson movement was not on Australian Jews, it would not be long before they were targeted.”[36]

The rivalry between the Leibler brothers over who had the right to speak on behalf of Australian Jewry was often fierce. One catalyst for a rift between the two brothers was when Mark Leibler and a delegation of ZFA officials met with the Keating government’s immigration minister Nick Bolkus when the government was considering the introduction of “racial vilification legislation” into the federal parliament. Mark Leibler’s Zionist Federation of Australia made a virtually identical submission to the government as Isi Leibler’s Executive Council of Australian Jewry. Gawenda notes that “Both organizations had long advocated for such legislation; both urged the government to include criminal sanctions for extreme forms of racial vilification.”[37]

The Racial Hatred Act was passed in 1995, adding to the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975 (itself a direct result of Jewish activism) the totalitarian Section 18C, which made it unlawful to offend, insult and humiliate or intimidate a person or group on the basis of color, race or ethnic origin. The 1995 legislation was a victory for Leibler and his communications director Helene Teichmann who had organized the meetings of leaders of ethnic communities that had “led to a unified position on the need for racial vilification legislation.”[38] It was clear to immigration minister Bolkus that “Leibler had been more active than any other Jewish leader in the campaign for the proposed extension of the Racial Discrimination Act.”[39]

Conservative commentator Andrew Bolt later fell afoul of Section 18C for some columns he had written questioning the ethnicity of light-skinned “Aboriginal” activists. Bolt, hitherto a Zionist shill and sycophant of organized Jewry, was stunned when his appeal to Mark Leibler to support the elimination of Section 18C was flatly declined. Gawenda observes that “Bolt seemed unaware that Leibler had played an important role in getting the 1995 legislation passed and would never support the repeal of Section 18C, not even to support Bolt, who had always seen himself as a strong supporter of Israel, unlike the left-wingers who opposed any change to 18C.”

Journalist Andrew Bolt: jilted paramour of organized Jewry

Journalist Andrew Bolt: jilted paramour of organized Jewry

A frustrated Andrew Bolt predicted that Jewish leaders would ultimately regret opposing changes to the Act, noting that: “The Jewish leaders now should look very, very deeply into their souls at what they have helped wrought and ask themselves, are you seriously safer now as a result?” Bolt’s reasoning is that under Section 18C Australian Jews will in future be precluded from criticizing the beliefs and actions of a growing and increasingly militant Australian Islamic community which will be increasingly hostile to Israel and the interests of Australian Jews.

Bolt fails to mention the only reason there are any Muslims in Australia at all (with all their myriad problems and social dysfunctions) is because Jewish activism succeeded in ending the White Australia policy and establishing multiculturalism as the basis for social policy. As the Jewish academic Dan Goldberg proudly acknowledges: “In addition to their activism on Aboriginal issues, Jews were instrumental in leading the crusade against the White Australia policy, a series of laws from 1901 to 1973 that restricted non-White immigration to Australia.”[40] As throughout the West, it is clear that the Jewish fear and loathing of White Australia trumps any concern about the anti-Semitic tendencies of the non-White immigrants that are being imported into the nation.

In 2014, the then Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott abandoned an election pledge to repeal Section 18C after coming under sustained attack from Jewish activist organizations. Gawenda observed at the time how “the repeal of section 18C was vigorously opposed by the leadership of virtually every ethnic community in the country. But it would be fair to say – without wishing to give succor to those who reckon the Jews are too powerful – that Jewish community leaders have played a crucial role in organizing the opposition to any potential change to the RDA. It is the opposition of the Jewish communal leaders that had been of major concern to [then Attorney General] Brandis and, to a significant extent, Tony Abbott.”[41]

Thanks to Australia’s Jewish-led demographic revolution and legislation like Section 18C, the Jewish lawyer and activist Ruth Barson is now confident that “the chances of the Holocaust occurring in Australia today are remote,” but cautions that history shows Jews are never truly safe, and consequently, “we should have no tolerance for even the shadows of racism and xenophobia. These are dangerous in any guise.”[42] Dvir Abramovich, chairman of the Anti-Defamation Commission (Australia’s version of the ADL), contends that “The horrors of the Holocaust did not begin in the gas chambers – but with hateful words of incitement and contempt, and with the demonizing of anyone who was deemed unworthy by the Nazis.” Accordingly, in addition to supporting the prosecution of “hate speech” through Section 18C of the Racial Discrimination Act, he insists “it’s time that compulsory teaching about the Holocaust is introduced in all Australian schools, to not only develop an understanding of the dangerous ramifications of racism and prejudice, but to heighten awareness of the value of diversity, religious freedom, acceptance and pluralism.”

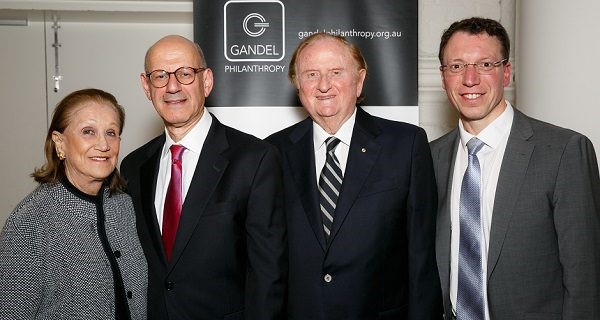

In early 2020, the Victorian government acceded to Abramovich’s demands and study of the Holocaust became mandatory in Victorian schools. Leibler’s friend and ABL client John Gandel will fund the development of new teaching resources which will be based on existing resources from Israel’s Yad Vashem memorial and lesson plans produced by the World Holocaust Memorial Centre in Jerusalem. Holocaust “education” has been compulsory in New South Wales schools since 2012.

In the 1990s, Mark Leibler successfully lobbied the Keating government immigration minister Nick Bolkus to have British historian David Irving banned from entering Australia. He reiterated the views of his brother Isi, then Executive Council of Australian Jewry President, who had described Irving as “a beer hall rabble-rouser and hero to the German neo-Nazis.” Both urged the government to follow the example of Canada and deny Irving entry into Australia. These overtures were successful and Irving was banned for being “likely to become involved in activities disruptive to the Australian community or a group within the Australian community” and for not being “of good character.” The entry ban was imposed despite Irving’s daughter residing in Australia.

Brenton Sanderson is the author of Battle Lines: Essays on Western Culture, Jewish Influence and Anti-Semitism, available here and here.

Go to Part 4.

[1] Michael Gawenda, The Powerbroker: Mark Leibler, An Australian Jewish Life (Melbourne: Monash University Publishing, 2020), 127-28.

[2] Ibid., 128.

[3] Ibid., 129

[4] Ibid., 130

[5] Ibid., 131

[6] Ibid., 128

[7] James Jupp, From White Australia to Woomera – The Story of Australian Immigration (Melbourne: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 46-47.

[8] Bronwyn Hinz, “Ethnic associations, networks and the construction of Australian multiculturalism,” Paper presented at the Canadian Political Science Association Annual Conference, Corcordia University, Montreal, 1‐3 June, 2010, 9-10. http://www.bronwynhinz.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/Hinz-2010-Australian-multiculturalism-paper-for-CPSA-v4.pdf

[9] Gawenda, The Powerbroker, 149.

[10] Ibid., 147.

[11] Ibid., 150.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 152.

[15] Ibid., 153.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., 154.

[18] Ibid., 155.

[19] Ibid., 174.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., 175.

[22] Ibid., 143.

[23] Dan Goldberg “After 9/11: The Psyche of Australian Jews,” In: New Under the Sun – Jewish Australians on Religion, Politics & Culture, Ed. Michael Fagenblat, Melanie Landau & Nathan Wolski (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2006) 146-47 & 149.

[27] Gawenda, The Powerbroker, 146.

[28] Ibid., 199.

[29] Ibid., 200.

[30] Ibid., 144.

[31] Ibid., 145.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid., 146.

[34] Andrew Markus, “Multiculturalism and the Jews,” In: New Under the Sun – Jewish Australians on Religion, Politics & Culture, Ed. Michael Fagenblat, Melanie Landau & Nathan Wolski (Melbourne: Black Inc., 2006), 99.

[35] Kevin MacDonald, The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth‑Century Intellectual and Political Movements (Westport, CT: Praeger, Revised Paperback edition, 2001), 303.

[36] Markus, “Multiculturalism and the Jews,” 99-100.

[37] Ibid., 178.

[38] Ibid., 179.

[39] Ibid., 180.

[40] Dan Goldberg, “Jews key to Aboriginal reconciliation,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, February 2, 2008.

[41] Michael Gawenda, “The real reason Abbott broke his promise on Section 18C,” The Australian, August 6, 2014. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/business-spectator/the-real-reason-abbott-broke-his-promise-on-section-18c/news-story/bc977f7be04dc1dab8eb1db52a5707ed

[42] Ruth Barson, “Holocaust remembrance teaches lessons for humanity,” The Sydney Morning Herald, January 26, 2016. https://www.smh.com.au/opinion/holocaust-remembrance-teaches-lessons-on-human-rights-20160126-gmdy21.html

Mark Leibler with former Prime Minister Julia Gillard: “A wholly-owned subsidiary of the Israel Lobby”

Mark Leibler with former Prime Minister Julia Gillard: “A wholly-owned subsidiary of the Israel Lobby”

Mark Leibler in the early 1990s

Mark Leibler in the early 1990s Former Prime Minister Paul Keating in the United States in 1993

Former Prime Minister Paul Keating in the United States in 1993 Former Prime Minister John Howard (second from right): leader of “probably the most pro-Israel government in a long time.”

Former Prime Minister John Howard (second from right): leader of “probably the most pro-Israel government in a long time.”  Journalist Andrew Bolt: jilted paramour of organized Jewry

Journalist Andrew Bolt: jilted paramour of organized Jewry Mark Leibler with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison

Mark Leibler with Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison John Gandel (center right) and ADC chairman Dvir Abramovich (far right)

John Gandel (center right) and ADC chairman Dvir Abramovich (far right)

Key Leibler lobbying targets Paul Keating and Bill Hayden

Key Leibler lobbying targets Paul Keating and Bill Hayden