A Commentary on the film “Quisling: The Final Days”

“Minister President Quisling addresses the nation.”

“Men and women of Norway, a few days ago, the world received the news that Adolf Hitler, the Führer and Chancellor of the German Reich, had died, as befitting a hero, at his command post in Berlin during his heroic effort to prevent the Bolshevik destruction of his country and of Europe. With Adolf Hitler’s passing, we have lost an historic character capable of creating an era in the history of humankind. If Europe does not go under, surely the future will acknowledge that the salvation of European cultural civilization was due to Adolf Hitler. His National Socialism made Germany into a mighty bulwark capable of breaking the red wave of Bolshevism. His life’s greatest tragedy was that he, despite all his efforts, was unable to bring about peace between England and Germany. Such an alliance would have ensured world peace and neutralized Bolshevism. I will not betray our cause. Nor will I let it succumb to lawlessness and Bolshevism.”

So begins the 2024 Norwegian language film, “Quisling: The Final Days.” Here’s a poster.

In the center is Vidkun Quisling, Norway’s head of state from 1940 to 1945, played by a Norwegian actor who looks remarkably like the real Quisling. On our left is his wife Maria, and on our right is Pastor Peder Olsen, whose diaries, the filmmakers inform us, inspired parts of the film.

I was struck by the favorable take on Hitler in Quisling’s speech. Where else have I seen Hitler put in a positive light in a film, fiction or documentary? Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 documentary, “Triumph of the Will” came to mind and that was it.

The part about Hitler trying to bring about peace with England doesn’t square with the officially sanctioned story about him. If Hitler didn’t want war with England, that would imply that the bombing of London was really the result of Churchill’s warmongering. What would have been Churchill’s motive to go after Germany as he did, including was he bought and paid for—the word is he was in major debt and needed help with that.

I came upon the Quisling film browsing Kanopy, a service of my local library. It’s an excellent list of both current and older films, including classics, to stream for free, four to six films a month dependent on how I use it. You can check to see if your local library subscribes to Kanopy.

The title caught my eye. I knew of Quisling. A notorious figure. Treasonous collaborator with the Nazis during the German occupation of Norway, sold out his country, persecuted Norwegian Jews. Executed after the war. He even has his own word: a quisling is a traitor.

I noted that the film has a top director, Erik Poppe, whose films include “The King’s Choice,” 2021, about three days in 1940 when the King of Norway is given a German ultimatum to surrender or die. Pastor Olsen is played by Anders Danielsen Lie, who was superb in the fine Norwegian film, also 2021, “The Worst Person in the World.”

I was drawn to the WWII setting. WWII, especially in Europe, is a monumentally significant historical event. Making sense of it contributes to a better understanding of the present time, including our (I’m an American) pre-occupation with Israel, a distant and small country 263 miles long and from 71 to 6.2 miles wide.

I streamed “Quisling: The Final Days” and was knocked out by it. Artistically top of the line—direction, cinematography, tour-de-force acting performances by the three leads, and a believable, engaging, and thought-provoking screenplay.

I find it intriguing how little attention has been paid to this film. It’s attracted very few reviews: Variety reviewed it and that’s it among major reviewers. The New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, the Roger Ebert site, nothing. If I hadn’t stumbled upon it browsing Kanopy, I wouldn’t have known about it.

I compare this Quisling film favorably to another foreign film, “Parasite,” a Japanese film that won the 2020 Academy Awards for Best Picture, Best Direction, and Best Original Screenplay. I write film reviews at Amazon under the pseudonym “Green Wave.” In my Amazon review of “Parasite,” I called it “expertly crafted, glossy, politicized tripe.”1 The Rotten Tomatoes site, which aggregates published film reviews, lists six reviews for “Quisling: The Final Days” and 495 for “Parasite.” Why the discrepancy? Figuring out how the public flow of information and ideas works, who controls it, will contribute to a better understanding of what things and people we attend to and what we make of them. Quick, name one Russian other than Putin.

Besides from Kanopy, “Quisling: The Final Days” is available for rental at Google Play. Amazon Prime has it free with ads, though personally, I prefer paying money to anticipating ads and dealing with interruptions. It’s also other places, check around.

If you plan on watching “Quisling: The Final Days,” you might want to stop reading this post after this paragraph and perhaps come back to it after you’ve seen it. The rest of this writing is a series of comments on the film. They include extended quotes from the screenplay and a lot of spoilers. I don’t want to get in the way of your fresh experience with the film more than I might already have with these preliminary remarks.

Personally, I stay away from reviews and analyses before I watch a film or read a book. I want to start cold, as it were, let whoever created it take me where they will and come to my own conclusions. If something particularly interests me, I go to what other people have had to say about it and compare what they offer to what I took from it.

One of the reasons I’ve taken the time to write up this post about the Quisling film is I found the few reviews and analyses of it I’ve read to be perfunctory and shallow. Whether I’m up to it or not, this fine film deserves careful and insightful consideration.

In what follows, I offer some disparate observations with the hope that they add up to something of worth. Incidentally, the wheels of justice turned much faster in those days than they do now. Quisling was arrested on May 9th, 1945 and executed on October 24th of that same year. This week as I’m writing this, mid-October, 2025, I read of the execution in the U.S. of a man convicted of murder in, I’m serious, 1993.

* * *

Lutheran Pastor Peder Olsen, a hospital chaplain who has not previously worked with prisoners, is assigned by his church superior to provide religious counsel and guidance to Quisling, whom they know to be a Christian.

Pastor Olson goes to see Quisling in prison. As he nears Quisling’s cell, the guard responsible for watching over Quisling remarks to him, “If he hangs himself, we can’t shoot the bastard.”

Peder peers into the dark, gloomy, barren cell at Quisling dressed in casual clothes sitting alone at a small wooden table. He introduces himself and says he has come to provide pastoral service, to be “someone to talk to, to help you clear your mind and find peace.”

“I am innocent,” responds Quisling firmly. “I have no unfinished business with church, God, or country. Psychiatrists seriously consider everyone in our movement as permanently mentally impaired. These so-called investigators want me to admit to being some sort of opportunist, a spineless Peer Gynt character with only self-interest in mind. I fought for my country for five long years, day and night. You don’t believe me? You think I only fought for riches, titles, salutes, stuff and nonsense? The armor of an insecure man? I couldn’t care less about any of that, I have acted according to my convictions. For that, I feel no shame.”

Attempting to establish a relationship with Quisling and knowing he has met with Hitler, Peder asks Quisling, “What was Hitler like?”

“A passionate man. You can always question the outcome, but he believed in something. You can’t say that about everyone.”

“Is that something you admire?”

“Belief? Of course. But I admire certainty even more. You can’t, like Hitler did, base your politics on belief. You need to know. Spend time finding the sources. To know. I’ve worked all my life on my philosophy, Universism. The actual truth. I’ve given myself the mission of lighting a candle for humankind. To find the true philosophy of life. In accordance with both science and empiricism.

“I’m sure Universism is very interesting,” says Peder. But what we really should aspire to are the words and deeds of Christ. Love.”

“Universism is the same thing, just greater,” says Quisling. It concerns—”

“Mr. Quisling, greater than love? What is greater than love?”

Quisling remains silent for several seconds, apparently unable to think of a reply, and the scene ends.

During Quisling’s silence, I pondered Peder’s question, which was really an assertion, that there isn’t anything greater than love. What came up for me during those moments is that, depending on the context, indeed there are other values or personal attributes, whatever to call them, that are at least on an equal plane with love, among them, honor, integrity, decency, generosity, respect, protectiveness, accomplishment, insight, and wisdom. Just now writing these last couple of sentences, I flashed on the title of an old song popularized by The Mills Brothers vocal quartet, “You Always Hurt the One You Love.”

Here’s a head of state talking about philosophy. I tried to imagine an American president—FDR, Truman, Eisenhower, Ford, Nixon, Reagan, the Bushes, Clinton, Obama, Biden, Clinton, Trump, any of them—expounding on philosophical precepts. It reinforced my impression that these days our political system is going to give us the likes of Kamala Harris and Donald Trump to choose from—no Jeffersons and Madisons.

This initial meeting between Quisling and Peder set up the relationship that is the spine of the film. Peder is bent on getting Quisling to acknowledge and confess his sins to God. A characteristic exchange between the two men:

“The Jews rejected Jesus Christ for Barabbas, a robber,” Quisling points out. “The same choice the world faces today. Many would prefer a Barabbas to a Messiah any day. I cannot accept such a thing. I need to fight to the very end! I’ll be more dangerous after my death.”

“You’re no Messiah, Vidkun. You’re a human being, a sinner, just like the rest of us. Do you have the courage to trust in the Lord? Do you trust me? Then you should ask the Lord to forgive your sins. Say, ‘God have mercy on me, a sinner.’ Say that to God. Don’t be afraid to say it. God will not forsake you. I will not forsake you. “

Most certainly, this is not Quisling’s wife Maria’s message to him. Maria’s contrasting outlook to Peder’s is a central element in this drama.

Peder goes to Maria and Quisling’s luxurious home—Quisling is in prison– to introduce himself. He asks her how she and Quisling met.

“We met in the Ukraine, my homeland,” she replies. “He was very famous. Captain Quisling. He saved thousands of lives during the great famine. Look at these. [Pictures of starving children and bodies piled up.] Thousands. Jews as well. I saw him for the first time through my office window. [She was a secretary.] I could tell straight away that this man could achieve anything. He was to be my destiny.”

During a visit to her husband in prison:

“Do not bow down! You hear me? Do not let anyone break you. There’s no one as strong as you. I knew that as soon as I laid eyes on you. ‘There’s a man who will not be broken,’ that’s what I thought. You are Captain Quisling. My Captain Quisling.”

Maria’s talking about the prosecutors in his court trial, but she’s also talking about Peder. This film raises the question of whether Christianity as a religion and Christian clergy promote what amounts to bowing down among adherents. It can be assumed that Peder has every good intention, but is he diminishing Quisling, making him self-deprecating and self-doubting, humbling him, making him compliant, subordinate to what arguably is an imaginary god, a young Jewish political insurrectionist from two millennia ago who never himself claimed to be divine, and to Peder himself. Was Quisling being pressured by both the legal process and a Christian minister to become less of a man? To director Erik Poppe and his screenwriter’s credit, based on their film, this question can legitimately be answered both yes and no, which puts “Quisling: The Final Days” on a higher artistic plane than something like the sophomoric, pedantic “Parasite.”

* * *

“Quisling: The Final Days” deals directly with the Jewish issue. What was Quisling’s culpability with respect to the treatment of Norwegian Jews during the occupation? It is a central aspect in Quisling’s court trial.

To help me make sense of this aspect of the film, I looked for a book that dealt with Quisling and Jews. A number of books have been written about Quisling, including in recent years, but from what I can tell, just about all of them are extremely biased against him. I did find one published back in 1966 that is reputed to be sympathetic toward Quisling, Quisling: Prophet Without Honor by journalist and biographer Ralph Hewins.2 I’ve read that Hewins got a lot of static for saying good things about someone who had said good things about Hitler. I obtained the Hewins book and found it a thoughtful and balanced account of its subject. It’s available in college libraries and Amazon sells reasonably priced used copies.

According to Hewins, Quisling was antisemitic, largely prompted by his deadly fear of an international Marxist conspiracy in which Jews played a central role. As for Jews’ place in Norway, Hewins quotes Quisling as affirming that

There are many who say that a Jew cannot be expelled from Norway simply because he is a Jew. In my opinion, no such reasoning could be more superficial. A Jew is not Norwegian, not European. Jews have no place in Europe. They’ve are an internationally destructive element. The Jews create the Jewish problem and cause antisemitism, and it is not difficult to understand why. The only possible solution is for Jews to leave Europe and to live in some area as far away as possible, preferably an island [he was thinking of Madagascar].3

Hewins reports that on October 26th, 1942, Quisling introduced a law confiscating Jewish property which was implemented in 126 cases. On November 17th of that same year, he decreed that all full-Jews, half-Jews, and quarter-Jews register with the nearest authorities.

According to Hewins, Quisling’s antisemitism did not run to genocide. In fact, he had saved thousands of Jewish lives during the Ukrainian famine during the 1930s. Hewins believes Quisling’s claim that he was unaware of the Nazi’s “final solution,” and that he was not forewarned of the deportation of around 1,000 Jews to Germany by the German SS and took no part in it. However, asserts Hewins, Quisling did not attempt to counteract the German initiative, and arguably that negligence as head of state was criminal. The major question in Hewins’ mind is whether it deserved a sentence of death.

In the film, there is this exchange in the court trial between Quisling and the prosecutor:

“It’s foul to accuse me of persecuting the Jews. I who have done such extensive humanitarian work. I am bold enough to say I’ve helped more Jews than anyone else in Norway.”

“Yet in various accounts you claim that Judaism in to blame for everything. And that the ‘Jewish troll’ must be conquered. What part did you play in the deportation of Norwegian Jews, Mr. Quisling?”

“I knew nothing.”

“You knew nothing? As head of the police, you knew nothing of the nature of this mission?”

“There was talk of them being sent to Poland. That’s all I knew.”

“You must have known something. You said on record that you visited the camps where thousands of Jews were sent in 1942.”

“Yes, and they appeared to be regular labor camps, work places. Nothing out of the ordinary. Nothing that left an impression on me.”

“Nothing that left an impression? Who knows what he must have seen!”

Peder didn’t believe Quisling about Norwegian Jews:

“How can you say you knew nothing? That’s your approach, twisting the story to fit your worldview. It doesn’t matter to you who gets sacrificed along the way, who dies.

“Are you referring to the deportation?”

“Of course I am! You knew! You held a fiery speech about the ‘Jewish problem’ shortly after the Donan [the ship carrying the Jews] left Oslo. You defended your actions.”

“The issue was complex. Much more complicated than you make it. First, I didn’t know everything.”

“You were Minister President!”

“Under great political pressure!”

“Innocent people were murdered. That is indefensible!”

“War has other rules! People die in wars! The Bolsheviks were much worse. I have proof with my own eyes. I spent eight years up to my knees in dead bodies! Who are you to teach me about suffering?”

Did Quisling know that the Norwegian Jews’ fate was not good and repressed it or chose to think otherwise? Or did he really not know? Did Roosevelt know about the fate of the Jews, did Churchill? To what extent do we have the capability to deny the truth about the world and about ourselves? To its credit, this film poses these questions.

* * *

In court, near the end of the trial.

“That I, who faithfully served my country, should be accused of treason while those who are truly responsible for this misfortune, who sabotaged the armed forces, who drove us into the war, go free! They may rejoice and say ‘Hah! we got him in the end.’ I know I aimed to do good. My actions have been solely for the good of my own people, and for the advancement of the Kingdom of God on Earth that Jesus Christ came to establish. I am not aware of doing anything to harm the people of Norway. I have done my utmost to keep the Nordic countries from becoming a theatre of war. [Norway had 324 war deaths. Finland’s total was around 80,000. England’s around 383, 000. The Roosevelt administration shipped enough young Americans to distant realms to run the total of deaths up to 405,000.] I have prevented civil war, tried to remedy the invasion and occupation, limit the enormous misfortune they caused the Norwegian people.”

“Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Quisling is hereby sentenced to death for crimes against the Military Penal Code.”

* * * ·

In a recent writing, I contrasted the way the 2024 film “The Order” portrayed events I dealt with in a book I wrote.4 My purpose was to get across that different storytellers can tell very different stories, and that we need to keep that in mind when we take in what anybody tells us. It’s especially important to keep in mind that we are prone to give credibility to visual portrayals of something—film, television, YouTubes—because we can see it happening. With fictional depictions, we realize those are actors and there’s a screenplay and it’s been edited, but there it is going on right in front of us. The same with documentaries: those pictures are the real thing, but the order in which they are shown and the meaning they are given in a voice-over and what isn’t shown can lead us to conclusions that aren’t warranted.

To illustrate my point in this recent writing, I contrasted the way “The Order” and my book depicted the death of a man named Bob Mathews back in 1984. I’ll do the same thing here with two accounts—the film’s and the Hewins book’s—of the execution by firing squad of Vidkun Quisling in 1945.

First, the account in “Quisling: The Final Days.”

The day of the execution, it’s just Peder and Quisling in Quisling’s cell.

In the evening, Peder shaves Quisling with a straight-edged razor, which adds an intimacy to their relationship.

Well after midnight, uniformed men enter the cell.

“It’s time.”

Quisling and Peder ride together in a van to the execution site.

During the drive, partly voice-over and partly in Quisling’s spoken words, from the Gospels of Mathew, Mark, and Luke:

“Behold the Son of Man is betrayed into the hands of the sinners.”

“And the soldiers led him away into the castle and they called together the whole band of guards. And they clothed him with purple and planted a crown of thorns which they put on his head.”

“And they led me out to crucify me. And they betrayed me into the place of Golgotha. It was the third hour and they crucified me.”

“And in the ninth hour, Jesus cried with a loud voice, ‘My God, my God, why has thou forsaken me?’”

“Father, forgive them for they know not what they do.”

They arrive at the execution site.

A uniformed official takes off Quisling’s handcuffs. Quisling turns and reaches back and hands his hat to Peder and says quietly, “Goodbye.”

Quisling’s arms are strapped to a wooden wall.

A blindfold is put in place. Quisling doesn’t want it. “I wish to look death in the eye,”

“These are the rules.”

A white circle is pinned to his chest.

The ten-man firing squad marches into place.

A long silence, the camera close up, just Quisling’s head and shoulders, a light shining on him. When will the shots ring out? The tension mounts.

Quisling shouts, “I am innocent! You are about to shoot an innocent man!”

From a distance, we see Quisling strapped to the wooden wall and the firing squad in place. They take aim. Shots. Quisling twitches and slumps, held upright by the straps. A soldier strides forward and shoots him in the head with a pistol.

Sometime later, Peder sitting in a field of grass holding the hat Quisling had handed him.

The film ends.

The Hewins book’s account of Quisling’s last day:

Quisling is informed that he will not be pardoned and will be executed that night. Hewins doesn’t say that it was Peder who gave him the news. In fact, Peder Olsen isn’t mentioned at all in Hewins’ book on Quisling.

Quisling spends part of his last hours writing a twenty-page summary of his philosophy of Universism.

He reads the Bible.

He speaks with the Bishop of Tønsberg, whom he tells, “I handed Norway to the King in good order. What would Norway have done without me?”

He writes a message to be sent to his followers. “Do not handicap yourselves with the idea of revenge, because the trend of events will avenge the wrongs you suffered, not only from those who initiated the prosecutions but also with the society that has permitted this lawlessness.”

When he was taken from his cell at 2:00 a.m. Oct 24th, 1945, he leaves his Bible open with this text underscored: “He shall redeem their souls from defeat and violence and precious shall their blood be in His sight.”

He shakes hands with each of the ten-man firing squad. He tells them, “Don’t allow your conscience to bother you in later years. You are acting under orders and doing your duty as soldiers.”

He is tied to a stake.

The bullets strike his heart.

When they take off his blindfold, his eyes are open.

Endnotes

- The Amazon review of the film “Parasite.” https://www.amazon.com/gp/customer-reviews/R1ZIKM6G7ARUP0/ref=cm_cr_getr_d_rvw_ttl?ie=UTF8

- Published by New York: The John Day Company.

- Hewins, p. 326.

- The writing: Robert S. Griffin, A Commentary on the Movie “The Order,” The Occidental Observer, posted June 21, 2025. My book: Robert S. Griffin, The Fame of a Dead Man’s Deeds: An Up-Close Portrait of White Nationalist William Pierce, Indianapolis: 1stBooks Library, 2001.

1892–1949 (59 years old)

1892–1949 (59 years old) Josephine Forrestal 1899–1976

Josephine Forrestal 1899–1976 22 Dead Goyim, Manchester 2017: “Don’t look back in anger…”

22 Dead Goyim, Manchester 2017: “Don’t look back in anger…” Two Dead Jews, Manchester 2025: “Jews are the canaries in the coal-mine! Strong action now!”

Two Dead Jews, Manchester 2025: “Jews are the canaries in the coal-mine! Strong action now!” Dr Denis MacShane, Rotherham MP and Jewish champion; Laura Wilson, Rotherham shiksa abused and murdered while MacShane worked for Jews (images from

Dr Denis MacShane, Rotherham MP and Jewish champion; Laura Wilson, Rotherham shiksa abused and murdered while MacShane worked for Jews (images from  Gideon guides the gullible goyim (image of Gideon Falter from

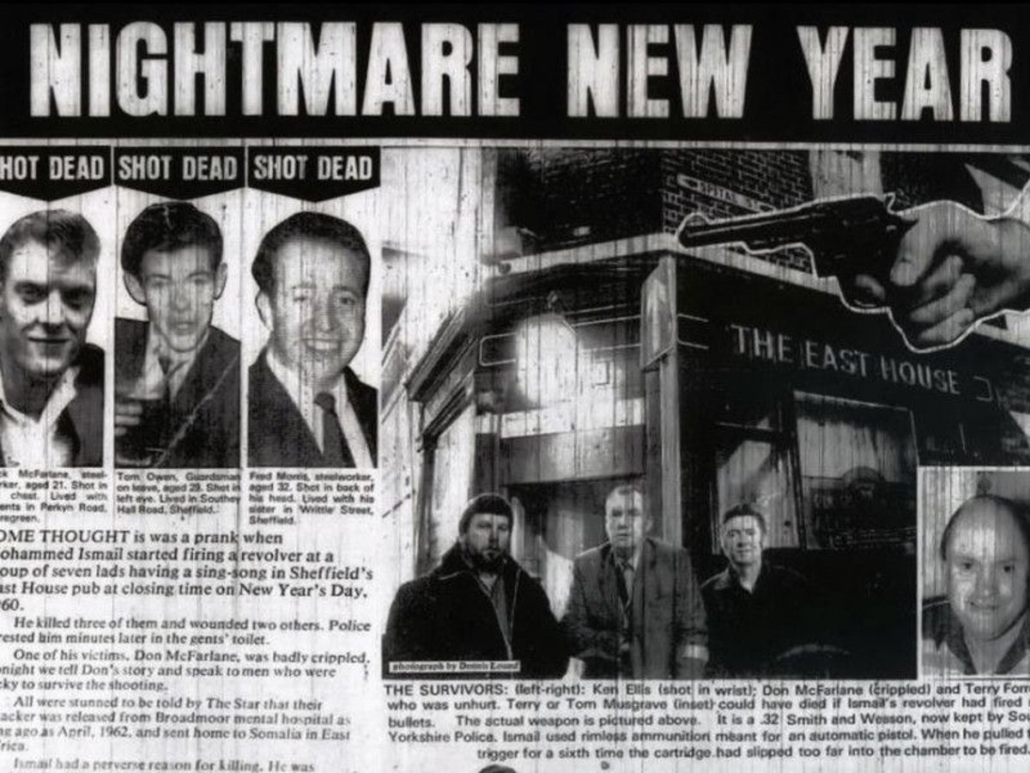

Gideon guides the gullible goyim (image of Gideon Falter from  Three Dead Goyim, Sheffield 1960, victims of a psychotic Somali (image from

Three Dead Goyim, Sheffield 1960, victims of a psychotic Somali (image from  Sue Berelowitz, the Jew “

Sue Berelowitz, the Jew “ Claire Waxman, yet another Jewish gatekeeper in high places (image from

Claire Waxman, yet another Jewish gatekeeper in high places (image from  A few of those fascinating insects known as termites (image from

A few of those fascinating insects known as termites (image from