Did Milton Friedman’s Libertarianism Seek to Advance Jewish Interests?

This is an abridged version of the original article, “Did Milton Friedman’s Libertarianism “Defend U$SIsrael Interests” that was was posted on Holy Crusade News.

In his Culture of Critique trilogy Kevin MacDonald shows how many Jewish intellectual movements have developed a culture of critique that undermines those ideas and values that protect White group interests and cohesion.

These Jewish intellectual movements include the Frankfurt School (philosophy, sociology), Boazian anthropology, Freudian psychoanalysis, the New York Intellectuals (literature), Marxism and even neoconservatism.

But how about libertarianism? Is it also a part of the Jewish run culture of critique?

MacDonald gives us a three-step method to answer the question:

1 “find influential movements dominated by Jews, with no implication that all or most Jews are involved in these movements and no restrictions on what the movements are.”

2 “determine whether the Jewish participants in those movements identified as Jews

3. AND thought of their involvement in the movement as advancing specific Jewish interests.” (Kevin MacDonald. Culture of Critique, pp. 11-12.)

The first step is easy. After all, libertarianism has clearly been dominated by Jews. The four biggest names in libertarianism are all Jews: Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises, Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard. Furthermore, they all dominated specific sub-schools of the libertarian movement: the Chicago school, Classical Austrian school, Objectivism and the Radical Austrolibertarian school. Also one of the most famous popularizers of libertarianism, Walter Block is Jewish.

The second and third step are more difficult. Therefore we have to study deeper into their lives and identities. First Milton Friedman:

MILTON FRIEDMAN

Milton Friedman was born on July 31, 1912 to Sara Ethel Landau and Jeno Saul Friedman, Jewish immigrants living in Brooklyn, New York. Milton was the youngest child and had three older sisters.

We do not know much about the Friedman family because all his life Milton Friedman was quite secretive about his family and ancestors—the only exception being in 1976 when he received the Nobel prize in economics and he had to write a short autobiography. But even then he did not tell much about his ancestors. He did not even mention that his ancestors were all Jews. In fact, the word Jew does not appear in this official autobiography.

My parents were born in Carpatho-Ruthenia (then a province of Austria-Hungary; later, part of inter-war Czechoslovakia, and, currently, of the Soviet Union). They emigrated to the U.S. in their teens, meeting in New York.

When I was a year old, my parents moved to Rahway, N.J., a small town about 20 miles from New York City. There, my mother ran a small retail “dry goods” store, while my father engaged in a succession of mostly unsuccessful “jobbing” ventures. The family income was small and highly uncertain; financial crisis was a constant companion.

Strangely Milton does not even mention that the birthplace and hometown of both of his parents was Berehove, a Hungarian town. One would think that the Friedman family would be interested in their ancestral town especially since there seems to have been no significant “anti-Semitism.” In fact, the town even had a mikve, a place for Jewish ritual cleansing.

Milton does mention that his parents came from Carpatho-Ruthenia but falsely claims it was a province of Austria-Hungary. Actually it was integral part of autonomous Hungary. The name Carpatho-Ruthenia is usually only used if one wants to emphasise that the area belonged not to Hungary but to “the forgotten people,” ruthenians/rusyns. In fact, only a very small part of the area was inhabited by them. For example, Berehove was majority Hungarian.

Carpatho-Ruthenia is a historic region in the border between Central and Eastern Europe claimed by Hungarians, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Poles, Russians and Romanians. Before World War I, the area belonged to Austria-Hungary and contained many Jews, just like the neighboring Austro-Hungarian Galicia. Many of the most famous Jewish economists came from this area, which is now part of Western Ukraine.

It does not seem likely that Milton’s parents – two young immigrants from Berehove – would accidentally meet in New York. Quite possibly their marriage was arranged by their families.

Curiously, nothing is known of Jeno Friedman’s parents or siblings. Geni.com has no info, nor does any other genealogical service; and there’s nothing in Milton’s Wikipedia entry. Furthermore, Milton seems to never have written anything about his grandfather or possible paternal uncles, aunts or cousins. Nor has Milton’s son David Friedman though he is very interested in history.

This is most curious for two reasons. First, family and genealogy have always been very important in Jewish culture. Second, Milton Friedman was extremely intelligent and that runs in families because intelligence is heritable. Where did Milton inherit his intelligence? Neither of his parents seem to have been very intelligent. They had no higher education and ran a small dry goods store. Milton’s mother’s Landau–Hartman family was very large but seems not to have been very intelligent or otherwise notable unless they were related to the famous Galician Landau family and Joachim Landau who was a member of the Austrian parliament. The famous libertarian economist Ludwig von Mises‘ mother came from this Landau family (Mises bio, p. 9). However, Landau was a fairly common Jewish family name so any direct relation between Berehove and Galician Landaus seems unlikely.

Friedman’s mentor was Arthur Burns who also mentored Alan Greenspan. (In his memoirs p. 63 Greenspan explicitly refers to Burns as “my old mentor”.) Wikipedia reveals that Burns was originally Burnseig but does not tell his original first name. Neither does any other source.

Burns was born in Stanislau (now Ivano-Frankivsk), Austrian Poland (Galicia), a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in 1904 to Polish-Jewish parents, Sarah Juran and Nathan Burnseig, who worked as a house painter. He showed aptitude early in his childhood, when he translated the Talmud into Polish and Russian by age six and debated socialism at age nine.[2] In 1914, he immigrated to Bayonne, New Jersey, with his parents.[1] (Wikipedia)

Also the young Milton Friedman had a very Jewish upbringing:

As a child, Milton had very strong ties to Judaism, studying in a Hebrew school and, in his words, “obeying every Orthodox religious requirement.” After a stint of extreme piety during the years before his bar mitzvah, he lost his faith and ceased Jewish practice, but he still strongly identified as a Jew and took great pride in both Jewish tradition and his Jewish heritage.

After his father’s death [1927] he faithfully recited Kaddish for the full eleven months, even traveling to neighboring communities to find a minyan. And he was a devout Zionist who strongly identified with Israel and expressed pride in its achievements. (Jewish Press)

In 1929 Milton got a scholarship to Rutgers University and became more secularized but never abandoned his Jewish identity. He became a socialist probably because at the time social beliefs were very common in the Jewish community. However, Milton’s political opinions started to change when at Rutgers university he became a student and protégé of Arthur Burns.

In economics, I had the good fortune to be exposed to two remarkable men: Arthur F. Burns, then teaching at Rutgers while completing his doctoral dissertation for Columbia; and Homer Jones, teaching between spells of graduate work at the University of Chicago. Arthur Burns shaped my understanding of economic research, introduced me to the highest scientific standards, and became a guiding influence on my subsequent career. … Arthur Burns and Homer Jones remain today among my closest and most valued friends. (Autobiography 1976)

Burns convinced Friedman that (relatively) free markets were even better for Jews than socialism.

In 1932 Milton got a scholarship to Chicago University where he met Rose Director who was two years his senior. The influence of Rose and the Director family on Milton has often been underestimated.

Rose Director was born in 1910 in Staryi Chortoryisk, Volhynia, Western Ukraine, Russian Empire. Wikipedia states: “The Directors were prominent members of the Jewish community in Staryi Chortoryisk.” Volhynian Jews were extremely bitter towards the Tsar because they had lost most of the ancient privileges they had enjoyed under Polish rule. However, with their capital and business networks they kept control of the economy. Jewish Virtual Library explains:

The Jews of Vladimir-Volynski (1570) and Lutsk (1579) were exempted from the payment of custom duties throughout the Polish kingdom. The Jews of Volhynia enjoyed the protection of the royal officials, who even defended their rights before the aristocracy and all the more so before other classes. With the weakening of royal authority at the close of the 16th and early 17th centuries, the Jews had the protection of the major landowners, mainly because they had become an important factor in the economy of Volhynia.

At the close of the 16th century, the noblemen began to lease out their estates to Jews in exchange for a fixed sum which was generally paid in advance. All the incomes of the estate from the labor of the serfs, the payments of the townsmen and the Jews (who lived in the towns which belonged to the estate), innkeeping, the flour mills, and the other branches of the economy were handed over to the lessee. During the term of his lease, the Jew governed the estate and its inhabitants and was authorized to penalize the serfs at his discretion.

During that period, a Jew named Abraham who lived in the town of Turisk became renowned for his vast leases in Volhynia. However, with the exception of these large leases, which were naturally limited in number and on which there is no further information from the beginning of the 17th century, many Jews leased inns, one of the branches of the agricultural economy of the estates, or the incomes of one of the towns or townlets.

A lessee of this kind was actually the agent and confidant of the owner of the estate and the financial and administrative director of the economy of the aristocratic class. As a result of his functions, such a lessee exerted administrative authority and great economic influence, a situation which embittered the peasants, the townsmen, and the lower aristocracy. The lease of estates, together with the trade of agricultural produce derived from them, constituted the principal source of livelihood of the Jews of Volhynia. ..

The emancipation of the peasants in 1861 and the Polish rebellion of 1863 caused far-reaching changes in the economic and social development of Volhynia that affected the Jews. The decline of the estates of the Polish nobility, the construction of railways, and the creation of direct lines of communication with the large commercial centers deprived the Jewish masses of their traditional sources of livelihood and impoverished them. This prompted the Jews to develop industry. Of the 123 large factories situated in Volhynia in the late 1870s, 118 were owned by Jews.

One thing is certain. Most Jews hated the Czar and preferred Austria-Hungary because there Jews were allowed greater freedoms.

According to Wikipedia the Director family emigrated to America in 1913 just before the First World War. Did the Directors emigrate because they had collaborated with the Germans and organized communist resistance to the war? Perhaps. After all, in America Aaron Director became a communist agitator who preached that a communist world revolution was imminent. However, at the same time he went to Yale! This probably indicates that the Director family had a lot of money or at least important connections.

[Aaron] Director was born in Staryi Chortoryisk, Volhynian Governorate, Russian Empire (now in Ukraine) on September 21, 1901.[1] In 1913, he and his family immigrated to the United States, and settled in Portland, Oregon.[1] In Portland, Director attended Lincoln High School where he edited the yearbook.[1]

Director had a difficult childhood in Portland, then a center of KKK and anti-communist hysteria in the wake of World War I. He encountered anti-Semitic slurs and was excluded from social circles.[2] He then moved east to attend Yale University in Connecticut, where his friend, artist Mark Rothko also attended. He graduated in 1924 after three years of study.[1] (Wikipedia)

It would be interesting to know the name of the Yale University dean of admissions who got the two immigrant communist Jews, Aaron and Mark into Yale.

Aaron graduated from Lincoln High in January 1921, and about that time the Yale University dean of admissions visited the school, with the result that Aaron and a slightly younger friend enrolled in Yale in the fall of 1921 as scholarship students. The younger friend was Mark Rothkowitz, later famous as an abstract painter under the name Mark Rothko. (ProMarket.org)

Not surprisingly Aaron and Mark detested Yale as racist and anti-Semitic. They anonymously published a satirical newspaper that accused Yale of being full of stupid anti-Semitic racists.

While at Yale, Director was influenced by Thorstein Veblen and H.L. Mencken, both elitist academics who believed the public lacked the intelligence to make democracy successful, and he eventually came to hold these views as well.[2] He and Rothko[3] anonymously published a satirical newspaper called the Saturday Evening Pest in which he wrote “the definition of the United States shall eternally be H. L. Mencken surrounded by 112,000,000 morons” and called for an “aristocracy of the mentally alert and curious.[4](Wikipedia)

Rothko dropped out of the university but Aaron stayed and graduated.

Rothko received a scholarship to Yale. At the end of his freshman year in 1922, the scholarship was not renewed, and he worked as a waiter and delivery boy to support his studies. He found Yale elitist and racist. Rothko and a friend, Aaron Director, started a satirical magazine, The Saturday Evening Pest, that lampooned the school’s stuffy, bourgeois tone.[8] (Wikipedia)

Mark and Rothko were especially irritated that sports played such a big role at Yale. They explained in their newspaper:

We believe

That in this age of smugness and self-satisfaction, destructive criticism is at least

as useful, if not more so, than constructive criticism.

That Yale is preparing men, not to live, but to make a living. …

That athletics hold a more prominent place at Yale than education, which is endured as a necessary evil. (ProMarket.org)

It is also probably safe to assume that they did not get an invitation to the elitist Skull and Bones. Nor did Yale administration look kindly at Aaron and Mark. Could it be that their antics helped uphold the Jewish quota at Yale? At the time Chicago had a reputation of being Jew-friendly while Yale and Harvard had a reputation of being “anti-Semitic”.

They evidently came under fire from the administration; their last issue contains a supporting letter solicited from Sinclair Lewis, a distinguished alumnus of Yale. Rothko did not return the next fall, and Aaron graduated in 1924 after only 3 years, probably to the relief of the Yale administration. (ProMarket.org)

After Yale, Aaron continued his socialist activism, became a teacher at a labor college and also traveled to Czechoslovakia.

He taught at a labor college in New Jersey, and he traveled to Europe, to England, and as far to the east as Czechoslovakia, before returning to Portland as an educational director at the Portland Labor College. (ProMarket.org)

Neoconservatism

After Lenin and Trotsky lost power to Stalin in the late 20’s Soviet Union, many Jews started to realize that capitalism could be better for the Jews than socialism. This realization and Stalin’s increasing anti-Semitism convinced many Jews not only to abandon socialism, but also to join conservatives in denouncing the Soviet Union. However, this did not mean that these Jews became conservatives. Instead they developed a cult around Trotsky that eventually morphed into neoconservatism that supported relatively free markets but allowed economic interventionism, modernist egalitarian values, secularism, philo-Semitism, open borders, and an interventionist foreign policy.

Like so many other socialist Jews, Aaron Director gradually became a neoconservative. He abandoned his promising career as a communist agitator and became a teacher of statistics at Chicago University. That in itself is quite amazing since he had been a high-profile communist agitator and only had an undergraduate degree even if it was from Yale. Obviously Aaron had powerful friends who kept helping him. One of those friends was the economist Paul Douglas whose wife was a wealthy Jewess, Dorothy Wolff.

In 1927, he [Aaron Director] decided to come to Chicago for graduate study in labor economics with Paul Douglas, then a member of our [Chicago] economics department and later a US Senator from Illinois. After 3 years as a student, Aaron joined the staff in 1930, teaching and assisting Douglas on a book on unemployment. (ProMarket.org)

Aaron also influenced the Jewish Paul Samuelson who would subsequently not only dominate economics education with his popular economics textbook but also win the Nobel Prize in economics. In fact, Aaron was Samuelson’s first teacher.

Aaron was evidently a very effective teacher— the Nobel economist Paul Samuelson recalls that it was a course of Aaron’s that introduced him to economics when he was a college student here and that course first excited his interest in the subject. (ProMarket.org)

Soon Aaron also helped Rose to become a student at the University of Chicago. It was also there in late 1932 that the Director family took Milton Friedman under their wing. Together with Arthur Burns they not only converted Milton to neoconservatism but also helped him in his career.

Paul Samuelson noted that it was Aaron Director and Milton Friedman who together created the second-generation Chicago school. Milton was the writer and Aaron the organizer who literally did not publish anything but used his network to organize an intellectual and political movement. (Samuelson interview, p. 528)

This Second Chicago school was not only much more Jewish and interventionist but also placed a greater emphasis on mathematics. Milton’s Essays in Positive Economy created a methodological revolution in economics. Deductive reasoning from the logic of action was replaced with fancy mathematical formulas, statistics and econometrics. Statistics and mathematical economics were needed for economic interventionism, especially in banking. Mathematics has a certain prestige in academia. It gives whatever one does an air of rigor and intelligence.

This extreme empiricist-positivist methodology was a success in the sense that it made neoconservative interventionist policy recommendations sound more scientific. Gradually the Chicago school took over a large part of academia and many private policy institutes to the extent that the Chicago school became almost synonymous with free market economics. Competing approaches, i.e., those with that were less mathematics-oriented, more conservative and less interventionist free market schools such as the Austrian school, were pushed to the sidelines.

Professor MacDonald has shown how neoconservatism is basically a Jewish movement that is part of the culture of critique. However, he did not write about the economic aspect of neoconservatism and that such economists as Arthur Burns, Milton Friedman, Aaron Director and Alan Greenspan were also important neoconservative intellectuals. They all were also active in the Republican party. Friedman was famously a close confidant of the neoconservative presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, whose Jewish grandfather Michel Goldwasser had emigrated from Poland. It was Goldwater who destroyed the last vestiges of the Old Right paleoconservatism and turned republicans into neoconservatives. Later Friedman would also be an advisor to presidents Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan who both had uneasy alliances with neoconservative Jews.

One reason why Friedman is not usually considered a neoconservative is because he often described himself as a libertarian. However, this is an example of deliberate confusion where Jewish intellectuals change the definitions of words. They needed to change the definitions of conservatism and libertarianism to include open borders (especially for Jews), a central bank-led banking cartel (often led by Jews) that finances an interventionist foreign policy that fights wars on behalf of Israel. This is why they needed to develop both neoconservatism and neolibertarianism. They were so successful that the true paleoversions of conservatism and libertarianism hardly even exist anymore. Now conservatism usually means neoconservatism.

Dynastic networks

Despite similar ideologies and backgrounds it took Milton Friedman and Rose Director six years to get married. Later Milton explained that they just had too little money.

What is often forgotten is that the Jewish bankers, such as Jacob Schiff, and communists worked together to topple the Tsar because the Tsar was seen as anti-Jewish. It seems that there were international bankers even in Trotsky’s Jewish Bronstein-Zhivotovsky family.

In fact, Schiff was quite open about his mission to destroy the Tsar. It was Schiff who had financed Japanese to attack Russia in 1905. It was also then that Trotsky’s revolutionary activities almost managed to topple the Tsar. Fear of banker power would also explain why the Tsar was so lenient towards communist revolutionaries and terrorists. Instead of executions, they were sent to Siberia from where they often escaped to the West. For example, after the 1905 Russian revolution Trotsky was only sentenced to Siberia and so allowed to escape to West again!

Foreign policy interventionism

Milton and Rose Friedman’s family backgrounds makes it easy to understand why banking and economics were so personal for them. It was literally about life and death for their families. First they helped to topple the Tsar and then Hitler. Banking and the economy had to be manipulated so as to finance the battle against anti-Semitism. Therefore it is also not surprising that Milton believed America should do everything in its power to crush Nazi Germany. This often led to fights with other students and professors who believed that America should stay out of the World War II. Wikipedia turns this into an anti-Semitic incident.

During 1940, Friedman was appointed an assistant professor teaching Economics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, but encountered antisemitism in the Economics department and decided to return to government service.[35][36] (Wikipedia)

However, later Wikipedia does note the pro-war attitude of Friedman.

In 1940, Friedman accepted a position at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, but left because of differences with faculty regarding United States involvement in World War II. Friedman believed the United States should enter the war.[39] (Wikipedia)

When America did enter the war, Friedman did everything in his power to help crush Germany. Despite now being a member of the pro-free market Chicago school, Friedman helped create the withholding tax which libertarians consider the most destructive tax of all.

From 1941 to 1943 Friedman worked on wartime tax policy for the federal government, as an advisor to senior officials of the United States Department of the Treasury. As a Treasury spokesman during 1942 he advocated a Keynesian policy of taxation. He helped to invent the payroll withholding tax system, since the federal government badly needed money in order to fight the war.[37] (Wikipedia)

It was the withholding tax that made the warfare-welfare state possible but Milton never had any regrets. Anti-Semites had to be destroyed.

I have no apologies for it, but I really wish we hadn’t found it necessary and I wish there were some way of abolishing withholding now.[38] (Wikipedia)

Banking interventionism

The original Chicago school was almost unique in defending the free market in banking. Many of the members of the school presented the Chicago plan which supported free banking and 100% reserves because money is the lifeblood of the economy. If you let the government control money and banking, it controls the whole economy. Milton agreed in principle that free market in money and banking is the best alternative, but in practice wanted the central bank to control the money supply and thus the whole economy.

Why this interventionist an exception to the rule of free market? Perhaps because banking is traditionally a Jewish business. Better bailouts than bankruptcies. Furthermore, without government bailouts gentiles might become upset during bank panics and blame the Jews. Better to have bailouts than anti-Semitism.

Friedman’s interventionist attitude was probably also encouraged by the fact that when he was studying at university, the chairman of the Fed was a Jew, Eugene Meyer. That was very important for Jews because it proved that they could also have powerful positions in the American economy like they had dominated the European economies.

Like his ancestors for over 2000 years, professor Arthur Burns taught his three top Jewish proteges— Milton Friedman, Alan Greenspan and Murray Rothbard—that Jews could and should have an active role both in politics and banking. Alliances with elites in politics and banking are two sides of the same interventionist coin. Professor Benjamin Gingsberg calls this strategy the Fatal Embrace because throughout history it has led to pogroms and other manifestations of anti-Semitism.

Rothbard had chosen the Austrian school over the Chicago school. He believed in the free market, the gold standard, free banking and 100% bank reserves because that would keep the state totally away from money and banking. This would also be good for Jews because then they could not corrupt the economy the way they had done in Europe. In fact, Rothbard believed that one reason why there had been so little anti-Semitism in America was because the banking system and economy in general had been relatively free. He greatly admired the early nineteenth century Jeffersonian-Jacksonian anti-bank movement that fought for free markets and even abolished the early American central bank.

Arthur Burns was surprised and dismayed by Rothbard’s libertarianism. Burns had expected something very different because he had been the neighbor and close family friend of the Rothbard family. Burns had even promised Murray’s father, David Rothbard, that he would take care of Murray. Apparently the idea was to make Murray into a successful economist and banker like his ancestors.

Burns had already mentored Milton Friedman to become an economics professor in the University of Chicago. Now Burns was mentoring both Alan Greenspan and Murray Rothbard who were almost exactly the same age. Both had East European Jewish ancestors. Murray was not only the most talented of Burns’ proteges but also had an illustrious ancestry full of businessmen and bankers. For some reason Murray never spoke about his banker ancestors, but two years ago the Mises Institute came into possession of an autobiographical essay written while Murray was still a high school student.

With remarkable honesty notes Rothbard writes how Jews had refused to assimilate in Poland.

My father has a very interesting and complex character, combined with a vivid background. Born near Warsaw, in Poland, he was brought up in an environment of orthodox and often fanatical Jews who isolated themselves from the Poles around them, and steeped themselves and their children in Hebrew lore. ..

When my father immigrated to the United States, at the age of seventeen, he had only this spirit to urge him forward. He had a great handicap in that he did not know any established language, since he had spoken only Jewish [Yiddish?] in Poland. The isolation of the Jews precluded any possibility of their learning the Polish tongue.

Rothbard tells more about his mother’s family but again fails to name names. For some reason he took them to his grave and not one historian seems to have studied the subject.

My mother’s background, though different, is just as colorful. Her family abounded in the traditions and characteristics of the old Russian aristocracy. My grandmother’s family, especially, had reached the highest pinnacle that the Jews in Czarist Russia could have achieved, One ancestor founded the railroads in Russia, one was a brilliant lawyer, another was a prominent international banker; in short, my mother’s family was raised in luxury and wealth.

So Burns had great expectations for Murray. Apparently Burns dreamed that together with Friedman, Rothbard and Greenspan, he would not only dominate academia but also American banking and thus the whole world economy. And now Rothbard refused to play ball!

Rothbard was appalled that the great Jacksonian anti-bank movement had been nullified by the creation of the Fed in 1913. Even worse, it was just a front for three mighty dynasties of the ruling elite: Morgans, Rockefellers and the Schiffs/Rothschilds. Rothbard saw history as a battle between liberty and the tyrannical ruling elite. He was totally against central banking that made the fraudulent and highly destructive fractional reserve banking possible. Bankers were literally the cancer of history. And Jacob Schiff with the help of Warburgs and Rothshilds was at the center of it. Rothbard wanted nothing to do with them!

The praxeological foundations of Murray Rothbard’s study of the ruling elite

Rothbard not only refused to embrace central banking and economic interventionism but also opposed the mainstream empiricist philosophy which used mathematics and statistics to manipulate the economy. Instead Rothbard embraced Aristotelian rationalist philosophy and Austrian School free market economics. Rothbard even started to think that all government statistical research bureaus should be eliminated so that it would be impossible for the government to regulate businesses and society in general!

Burns was not amused especially since he was director of research at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) and a Fellow of the American Statistical Association. He soon started to sabotage Rothbard’s studies. Burns even blocked Rothbard’s PhD thesis The Panic of 1819 because it claimed that America’s first depression was the result of central bank overexpanding the money supply. Only many years later when Burns left Columbia University to government service did Rothbard finally get his PhD.

But the intellectual war was only starting. For the rest of his life Rothbard would criticize Arthur Burns, Milton Friedman, Alan Greenspan and all other interventionists as statists and socialists. Often when Friedman wrote a book, Rothbard answered with his own book that showed the errors of Friedman’s logic. The most dramatic episode of this intellectual war dealt fittingly with the monetary history of the United States.

In 1963, together with Anna Schwartz, Milton Friedman published his magnum opus, A Monetary History of the United States. It blamed the Fed for the Great Depression because it did not expand the money supply and so could not bail out enough banks.

In the very same year Murray Rothbard published his own book America´s Great Depression which had a diametrically opposite analysis. Rothbard blamed the Fed for expanding the money supply too much and bailing out banks!

Rothbard believed that if you let banks fail the economy will soon recover like it did in 1921. Of course, some depositors and especially bankers would be wiped out, but that would teach them a lesson for trusting fractional reserve banking. Rothbard did not deny that such shock-therapy might create an anti-Semitic anti-bank movement, but he seemed to considered it a bonus! After all, what was needed was to destroy the fractional reserve banking altogether and reform the monetary system with pure gold standard and 100% reserve banking.

Burns and Friedman were enraged by Rothbard’s book. (According to rumors Greenspan was not enraged but rather amused and almost sided with Rothbard until Burns had a small chat with him.) Instead of answering Rothbard’s arguments they did their best to stop Rothbard from gaining a position in any university. Finally, years later, Rothbard did manage to obtain a position as a professor but only in an obscure community college. However, in the end Rothbard did sort of win the battle of ideas because Paul Johnson cited Rothbard’s thesis in his international best seller, Modern Times.

On the other hand, Friedman won the political battle since Burns and Greenspan took over the Fed, destroyed the last vestiges of the gold standard, and started feverishly expanding the money supply to finance the American welfare-warfare state. Each time there was a threat of a depression they greatly expanded the money supply. This is now standard practice, and interest rates have been pushed down to zero with dangerous consequences. Now the whole world economy is at the brink of abyss of debt.

Zionist interventionism

Considering their backgrounds it is not surprising that Milton and Rose were also fanatical Zionists. In practice libertarianism and Zionism are incompatible though for some reason there has lately been hardly any discussion about this obvious fact in (neo)libertarian circles. Indeed, they were not only Zionists but hard-core Likudniks. They often visited Israel and were very supportive of the extreme-right Likud party which has obvious terrorist roots. Milton even seems to have supported the annexation of the Palestinian West Bank. In his Newsweek column, he downplayed the occupation and even stated: “I had no feeling whatsoever of being in occupied territory.”

Perhaps the Palestinians had a different feeling.

U$Srael

Friedman not only identified as a Jew but was ready to ignore his libertarian principles when the interests of Jews were threatened. This is why he helped to institute the most dangerous and anti-libertarian tax of all: the withholding tax. And after Germany was destroyed, he fully supported not only the creation of Israel but also its expansion as an occupying power. Friedman seems not to have strongly opposed the huge subsidies America sends to Israel every year.

Burns, Friedman and Greenspan seem to have been the brains and architects of the petrodollar system. The idea was to get off the gold standard which limited the expansion of the money supply and therefore the capacity to bail out banks and whole countries. America went off the gold standard in the early 70s when Arthur Burns was the chairman of the Fed. Milton had already laid the groundwork for this exit in his 1953 Essays in Positive Economics by claiming that flexible exchange rates have huge benefits. Ironically, it was Friedman who was the greatest foe of the gold standard despite admitting – only in principle, of course – the moral and economic superiority of the gold standard.

But how to maintain the value of mere paper dollars especially when their amount increases exponentially? Simple: Artificially increase the demand for dollars. Just make sure that international trade and especially oil trade takes place in dollars. All you need is US-Nato war machine that forces all countries to use dollars in the international oil trade. Naturally this suited well the old allies of Israel, the Saudi family. And if some countries like Iraq or Libya refuse to trade their oil in dollars, then it would be easy to either organize a color revolution or if that fails then just bomb them into submission.

All this also fitted very well with the Jewish neoconservative world view where Russia is the enemy. Russia certainly has been biggest obstacle of Israeli expansionist foreign policy. The Fed and the petrodollar system were especially needed to destroy the Russians who stubbornly continue to cling to their nationalism and “anti-Semitic” alliance with Arabs. The Russians even have the gall to support Syria and other opponents of Israel in the Middle East.

The Friedman-Director family had an impressive enemies list and track record: Tsar, Hitler, Soviet Union and finally Putin’s Russia.

With the support of the petrodollar system the Fed could expand the money supply as much as necessary to defend both American and Israeli interests.

Libertarianism vs. tyranny

Rothbard was right. Friedman was no supporter of free market. On the contrary. Friedman together with Burns and Greenspan continued the ancient Jewish tradition of court Jews creating monopoly state capitalists.

So it is easy to answer Kevin MacDonald’s three questions:

- Libertarianism and its Chicago subschool have been dominated by Jews such as Milton Friedman

- Milton Friedman strongly identified as a Jew

- Milton Friedman deliberately used the libertarian movement to advance specific Jewish interests

But why was Rothbard virtually alone in noticing all this? Because Friedman was a brilliant propagandist. He presented himself as a free market supporter even if he was only relatively more libertarian than socialists. But more importantly Friedman was a good liar. This could be seen in his famous article Capitalism and Jews where he claimed that Jews have usually not benefited from government-granted privileges.

To summarize: Except for the sporadic protection of individual monarchs to whom they were useful, Jews have seldom benefited from governmental intervention on their behalf.

How could Friedman be so mistaken? Or rather, such a brazen liar He must have known the truth. His own ancestors came from Eastern Europe where for many centuries Jews had been the king’s privileged state capitalists. For thousands of years Jews had been slave traders, tax-farmers and almost everywhere in Europe enjoyed state granted business and banking cartel privileges.

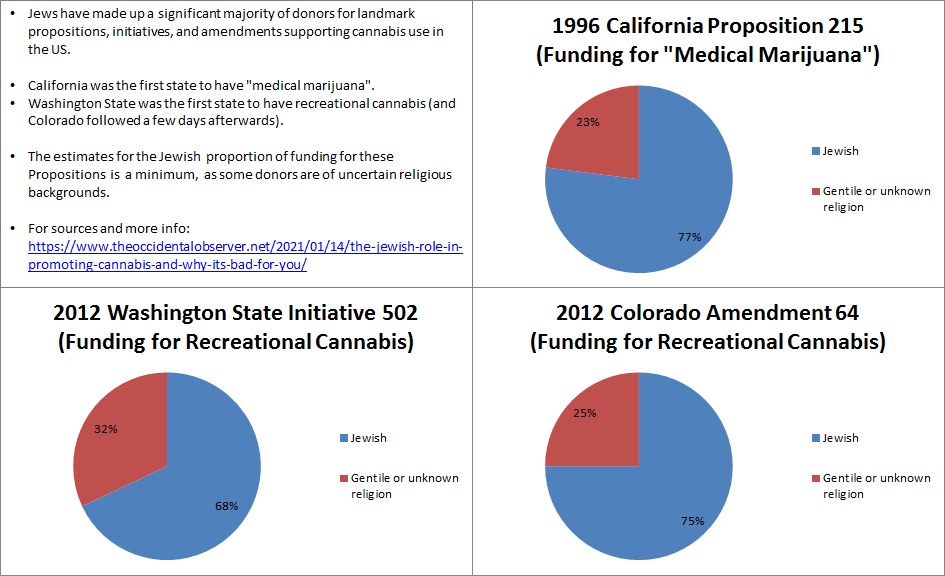

That Jews should be involved in the promotion of cannabis should come as a surprise to no educated person. After all, in centuries past the Sassoon family (“the Rothschilds of the East”) grew wealthy plying opium on the Chinese, resulting in the Opium Wars. In more recent years, the Sackler family turned enormous profits pushing the opiate Oxycontin (which the Sacklers knew to be addictive) upon American Whites. While many articles have been written in the dissident right on these topics, the normalisation of cannabis has happened with seemingly less attention. Mentions of cannabis are typically made in passing, perhaps due to the association of anti-cannabis sentiments with mainstream conservatism.

That Jews should be involved in the promotion of cannabis should come as a surprise to no educated person. After all, in centuries past the Sassoon family (“the Rothschilds of the East”) grew wealthy plying opium on the Chinese, resulting in the Opium Wars. In more recent years, the Sackler family turned enormous profits pushing the opiate Oxycontin (which the Sacklers knew to be addictive) upon American Whites. While many articles have been written in the dissident right on these topics, the normalisation of cannabis has happened with seemingly less attention. Mentions of cannabis are typically made in passing, perhaps due to the association of anti-cannabis sentiments with mainstream conservatism.

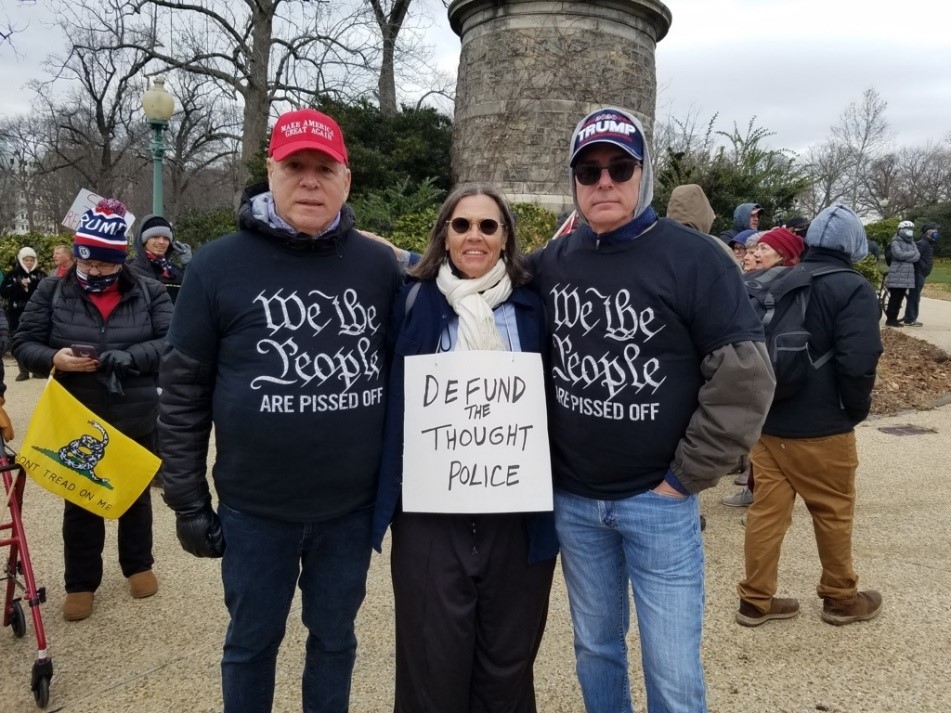

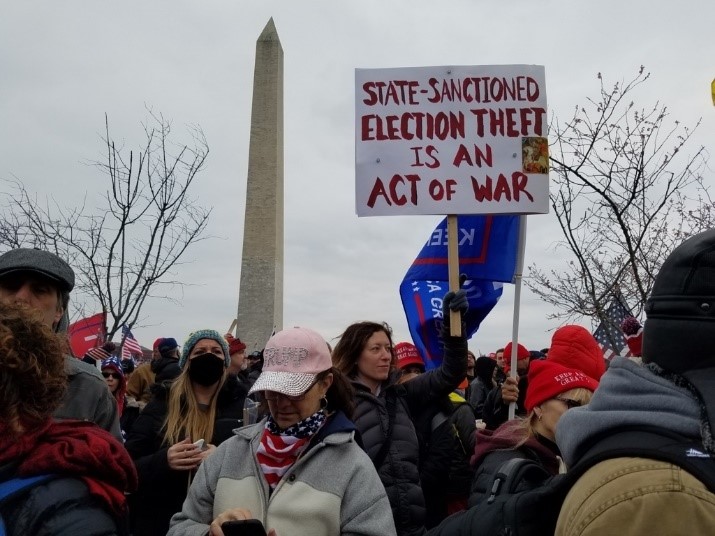

For a crowd this size and in light of the crimes that had been done against our country, the heightened energy flowing amongst us could have been combustible. But we protesters had about as much malevolence as an energized Superbowl crowd.

For a crowd this size and in light of the crimes that had been done against our country, the heightened energy flowing amongst us could have been combustible. But we protesters had about as much malevolence as an energized Superbowl crowd.