Go to Part I.

Go to Part II.

Part III. Separatist Solutions

As Lincoln observed in 1857 (see quote at beginning of Part II) racial preservationism logically leads to racial separatism. But not all preservationist proposals are equally effective at achieving that end. Some are not even intended or designed to do so in any meaningful sense. Others intend well, but have flaws in the design that would prevent them from preserving the White race even if they were implemented.

The range in scale of possible acts of racial separation is extreme. At the micro level it consists of a White individual, family or small group moving away from non-Whites to an area that is all-White or almost so—an act that has already been repeated so many millions of times it has acquired the sociological label of “White flight.” Such an act is not only racial separatist, but also racial preservationist, as it increases the likelihood that offspring will reproduce within their own race, although the more likely purpose of an ingathering is to create an informal community that can provide mutual security and support without attracting unwelcome attention. The difference between separatist and preservationist actions at the micro and macro levels is not in kind but in degree. At the micro level little is required and little is accomplished. At the macro level, the requirements are far greater, and so is what can be accomplished. Political power is necessary, and this requires the support and active participation of millions. The recognition of this necessity should inform all our deliberations. We should plan and act on the assumption that nothing sufficient, and therefore ultimately meaningful, can be accomplished, or is even possible, until we are in power, and then any proposal will be possible. Gaining that power will require the support of at least a majority, and probably a super-majority, of Whites for our solution. Winning the hearts and minds of our people for the preservation of their kind is more than half of our battle. It is the decisive battle which will decide the war. The specifics of our solution, as detailed in our proposals, will be central to winning that support.

Undetermined or Unspecified Solutions

Some White advocates hold a position without clearly stated solutions. Instead, they avoid the subject in the belief it could alienate supporters, so they have no tangible goal. Others only refer to vague or unspecified solutions, perhaps using the generalized terms “separation” and/or “ethnostate,” but without the specifics necessary to make them seem like something that could possibly become real. These positions can also be based on the belief that it is better for individuals to reach their own independent conclusions about a solution. In either case they view detailed solutions as a negative rather than a potential positive. They oppose the belief that offering a racially preservationist solution would be a net positive in attracting support and indeed essential to give substance and direction to a movement by providing it with a concrete goal.

Insufficient Solutions

Some White advocates accurately describe the full existential gravity and scale of the problem, but propose solutions that are woefully insufficient and incommensurate in scale. Perhaps they are so intimidated by the scale of a commensurate solution that they shrink from the prospect. But a sufficient solution, by definition, must be commensurate in scale with the problem to be solved or it cannot be a contender for serious consideration. The scale of our problem is extremely large, and so a sufficient solution must be as well. It is common for people, even fully informed White advocates, to be unable or unwilling to think big. Or they may be afraid to envision a solution commensurate in scale with the problem. We must overcome this fear or it will overcome us.

From its antebellum beginnings, separatist thought traditionally centered on the sufficient solution concept of a deportation of non-Whites and their resettlement in another country or countries. Around 1970 there was a paradigm shift in separatist thought that went all the way from a quest for victory to sauve qui peut—from the sufficient solution of a complete deportation of non-Whites to insufficient solutions, usually in the form of a partial White secession, that effectively surrender the far greater part of the White race and its territory. Richard Butler was an early proponent of such an insufficient solution, and his influence caused the concept to focus on a homeland for a small minority of Whites in the northwestern region of the country, with others like Michael Hart, Harold Covington and many subsequent movement writers and activists following in his path. Curiously, the concept of partition, which in its “National Premise” form is a sufficient solution, was passed over by this shift with scarcely a mention outside the pages of Instauration, and remains largely ignored.

Judged by the goal of White racial preservation and independence, all secession and similar insufficient solution plans I am aware of share four major flaws. The first is that they are all intended and designed to preserve only a lesser fraction of the White race, surrendering the majority to destruction in the larger multiracial nation. The second is that they are designed to include only a lesser fraction of the national territory (usually where only a small fraction of the White population resides), with the far greater part retained by the multiracial nation. The third is that they allow the still existing and larger multiracial nation to be the continuation of the United States, and still a nuclear and economic superpower with overwhelming military supremacy over North America and possibly effective dominance over Europe. The fourth is that they are cut off from lines of communication with Europe—an indication of their lack of consideration for Whites outside of the U.S.

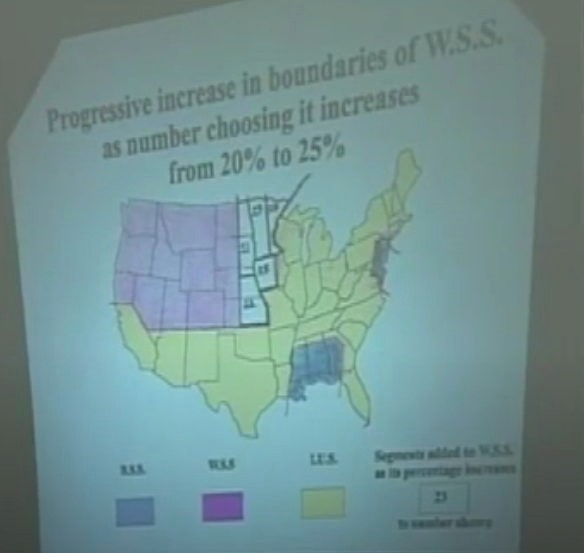

Figure 10: Michael Hart’s racial partition map of the United States as presented at the 1996 American Renaissance conference

I was in the audience at the 1996 American Renaissance conference when Jewish astrophysicist Michael Hart presented a separatist proposal titled “Racial Partition of the United States,” based on a voluntary three-way partition,[16] which I understand he has since disavowed. It is the most detailed plan for an insufficient solution that I have seen and shares the racially harmful flaws typical of secession and other insuffcient plans, starting with the critical flaw of being voluntary. His “White Separatist State” or “WSS” would be located in the northwestern part of the country, and in his most optimistic scenario (the purple and white areas in map in Figure 10) only 32.4% of “whites” would choose to live there (62.5 million of the 193 million “whites” in the 1990 census and 25% of the total population). Hart apparently presumed blacks would be much more enthusiastic about separation than “whites,” as in the same scenario he estimates 85.3% of them (25 million of the 29.3 million in the 1990 census) would choose to live in his “Black Separatist State” or “BSS” (the two gray areas in map in Figure 10, apparently including the national capital and Philadelphia, the previous capital). His

third country, the integrated state, will be a continuation of the present United States of America, but with a reduced area. All American citizens who do not explicitly choose to become citizens of the BSS or the WSS will remain members of the integrated USA.

This multiracial nation of 162.5 million (the yellow area in map in Figure 10) would contain 65% of the total population, and 67.6% or 130.5 million of the “white” population, in the 1990 census, and a proportionate amount of its territory.

Hart’s presentation never mentioned racial preservation as even part of the motive or purpose for his plan. Insufficient solutions in general cannot do so in good faith, as explicitly surrendering the majority of the race to the destructive embrace of multiracialism is the opposite of preserving it — it is offering it up for destruction.

Insufficient solutions like secession plans and Hart’s partition plan show little consideration for the fate of the majority of the White American population and no regard for the White populations outside the U.S. Also, next to its own physical existence, the most valuable physical possession of a race is its territory. As a result, such plans, by unnecessarily surrendering the far greater part of that territory, must also be regarded as contrary to White territorial interests. In the context of racial preservationism, they are only a more developed form of “White flight,” appealing to a small minority of disaffected Whites and racial survivalists who are fleeing the larger racial cause and accepting White defeat by surrendering the far greater part of their race and its territory.

A sufficient White preservationist solution requires the replacement of multiracialism by separation, with the great majority of Whites being united in an all-White country or countries. The surprisingly varied proposals to continue multiracialism in the supposedly White country, by including non-Whites in various degrees, therefore do not meet a sufficient preservationist standard in design. Such plans are typically based on certain designated racial proportions in the population. Some only seek to ensure the continuation of a simple White majority country, with a non-White minority population theoretically as large as 49 percent, and would therefore presumably not require any separation but only to stop non-White immigration and somehow prevent racial intermixture and the non-White birthrate from exceeding the White. Others seek to maintain a White super-majority or to reduce the proportion of non-Whites to perhaps 5 or 10 percent. These plans seem to be based on the fallacy of multiracial stasis, or the idea that an overgrown garden can be pruned back to its ideal state.

The first solution, a simple White majority, is already too late for the U.S. to achieve without removing some of the non-White population, given that the under-thirty population is now minority White. But any multiracialist solution is qualitatively insufficient in terms of racial preservation and independence, as it would limit or effectively negate White racial independence (i.e., control of its own existence) and result in racial intermixture with the non-White elements — either blending with a large 20–49 percent non-White minority or assimilation of a smaller (below 20 percent) non-White minority — resulting in White racial destruction. Given that the U.S. White population (as of 2015) is genetically 98.6% European, accepting a limited infusion of even 5% non-European genes would create a genotypic shift that could be expected to produce significant and visible phenotypic effects. This is antithetical to the most essential principles of racial preservationism, and since reducing the non-White proportion of the U.S. population to 10% would still require the separation and removal of over 100 million non-Whites, or over three-quarters of them, it raises the question, “Why stop there, at that point, instead of going all the way when you’re most of the way there.” It seems arbitrary, unless the intent and purpose of the plan is based on something other than White racial interests, such as an idealized multiracial stasis that is “gone with the wind.”

There are also what might be called “limited” multiracial plans that permit the inclusion of certain categories of non-Whites in the ingroup, such as Asians (permitted in Hart’s plan among others), but exclude other categories, such as Blacks. Such plans indicate that the purpose is to separate from certain negatively-regarded races but not the preservation or independence of the White race. Such plans are motivated by negative emotions regarding the excluded non-White races rather than positive feelings for the White race. Other limited multiracial plans would include mixed-race half-Whites — i.e., the mixed-race children of Whites and non-Whites — in the White country without any apparent awareness of the numbers involved or the consequences. If their numbers were so low as to be assimilable without harmful racial effect it wouldn’t be worth making an issue of them, but that is not the case and never really was. If the mixed-race children of earlier generations had all been blended into their White line instead of the great majority being assimilated into their non-White line, the White population today would have a proportion of non-White ancestry much greater than the 1.4% it actually has.

Lastly, there are plans that feature idiosyncratic proposals with little or no connection to racial preservation. Examples include plans that would require adherence to a particular ideology and would exclude a large part of the White race, perhaps the majority. Other examples are plans that would divide the White population into multiple separate nations, e.g., separating the Whites of Ohio, Oregon, Massachusetts, Florida, etc. from each other. Such divisions of the race, whether territorial or ideological, serve no racial preservationist purpose, and indeed no pro-White purpose, as such divisions would be harmful to White interests by placing the White population in a much weaker position both continentally and globally vis a vis other races.

Even if well-intentioned, the insufficient solutions briefly surveyed above would do more harm than good for White racial interests. Some could hardly have been better calculated as spoilers to sow division and to minimize White support, to divert attention from better plans, or be so unfavorable to Whites that many give up and despair of separatism itself. In varying degrees they deviate from what should be the guiding purpose of racial separation — racial preservation. Plans designed to preserve only a minority of the White population, or to enable its intermixture with half-Whites, cannot be accurately described as preservationist.

Sufficient Solutions

An important consideration for White preservation is that the White race is not a single homogeneous population, but a group of populations with great variety and diversity within the group yet distinct genotypically and phenotypically from the populations outside the group. A sufficient solution for White racial preservation should also preserve that sub-racial population diversity. To do this in the European homelands is a relatively straightforward matter of maintaining the historical or native populations in the different European nations by limiting migration between them to normal historical levels. As Ronald Reagan famously said, “Let Poland be Poland.” I would add “forever.” Let Poland be Polish forever, and the same for every European nation. “There’ll always be an England” said a song from racially more certain and happy times, to which should be added the caveat “only if it’s always English.”

Preserving the varied European population types in the New Europes outside of Europe is a less straighforward matter. Over 80% of the European migration to South America came from Southern Europe and to North America from Northern Europe. In both continents the combined European elements have essentially amalgamated into a single people to a degree that makes their division neither practical nor desirable, but their primary Northern or Southern European identities can and should be preserved by controlling the proportions of future immigration.

As noted, the most common concept of a separatist solution among pro-Whites until the 1970s was the removal of non-Whites by deportation. This followed the tradition of Abraham Lincoln’s 1862 proposal to a delegation of Black leaders to resettle the Black population of 4.5 million in Central America.[17] At that time the concept of White secession would have been seen as something for losers who were giving up and running away. Whites were supposed to remove the non-Whites from their country, not give it to them and remove themselves.

What has changed since the 1960s is the number of non-Whites in the formerly all-White, or over 80% White, countries has grown so large that it is hard to imagine any non-White country that would be willing and realistically able to accommodate the deportees. Partition provides a place to put them, in territory that is controlled by the country conducting the partition. But for the countries of Europe a partition solution is not even remotely practical, just or acceptable. They could not part with even the smallest fraction of the territory needed to provide such a place. Every square centimeter of Europe is part of their ancient racial homeland, and has been so since time immemorial, whereas — with the exception of the circa 1.2 million Jews — over 99% of the non-White elements have only been there since after 1945, after the postwar triumph of the Anti-White Coalition that opened the gates to their invasion. They have no valid historic or moral claim on any European territory. Removal of all the non-Whites from all of Europe is the imperative for the preservation and independence of the European peoples. But where would those 49 million (as of 2020) non-Whites go, or where could they be settled? A racial partition of the United States could provide enough territory for a non-White multiracial country to also accommodate the non-Whites now in Europe, Canada and Australia, if all the countries were to act together in a coordinated common effort. For Europe this separation would take the form of a deportation, but for the White race as a whole — and for all the non-Whites in Europe and the New Europes of North America and Australia — it would actually be in the form of a partition, with the territory for the new non-White country or countries provided by the United States.

The difference between non-sufficient solutions like secession and sufficient solutions like the “National Premise” concept of partition is the difference between the surrender of most of the White race and its territory and a White victory that succeeds in preserving most of the White race and its territory. The first is a small White rump state that spins itself off from a country seen by Whites as no longer theirs. The second is a majority, preferably super-majority, of the White population spinning off the non-White races into a separate country while keeping the greater part of the country. This is the White repossession Wilmot Robertson referred to by the Latin term “instauration.” In the April, 1976 issue of Instauration he coined the phrase “National Premise” to describe the partition concept in its sufficient solution form. An example of the “National Premise” partition concept can be seen in the map of my third (2020) proposal in Figure 11.

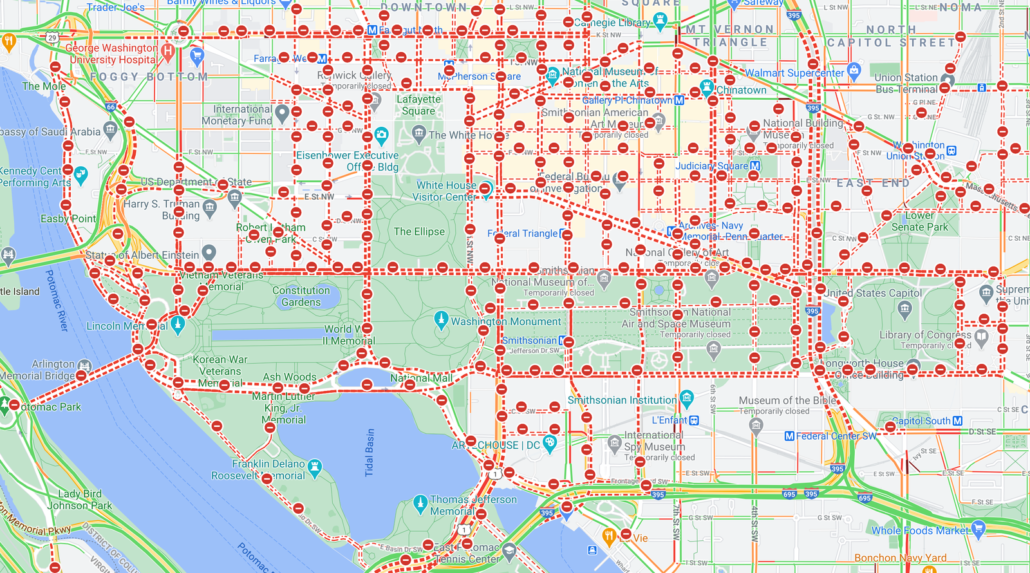

Figure 11: Map of the Third McCulloch Partition Proposal (2020)

In this proposal there would be a three-way partition into:

- A White American nation with a contiguous area of 2,225,841 square miles, 75.1% of the “lower 48” area of 2,962,031 square miles for the racial group that was 81.1% of the population in 1970, i.e., at the beginning of the massive non-White immigration promoted by the Anti-White Coalition. Alaska would be retained by the White nation. Hawaii would be divided, with the White nation retaining the 597 square mile island of Oahu as a White state — to secure the lines of communication across the Pacific to Australia and New Zealand — and the 4,028 square mile “Big Island” of Hawaii as a place for non-Whites after the partition. The other islands (Maui, Kauai, Molokai, Lanai, etc.), totaling 6,306 square miles, would be an autonomous, and possibly independent, state for the native Hawaiians and other Polynesians. The White American nation would be the continuation of the historic American nation with the national capital and all of the original pre-1803 territory, and most of the post-1803 territory, where circa 82.5% of the White population already live.

- An Amerindian nation with an area of 66,798 square miles.

- A non-White multiracial nation with an area of 669,392 square miles, making it the seventeenth largest country in the world at 3.19 times the size of France. It would be assigned all non-Whites, which would include all mixed-race or multiracial persons who are part-White but who are outside of the normal European phenotypic range. White Hispanics who identify as Hispanic rather than White could choose to live with the non-White Hispanics in the multiracial nation. White parents and grandparents of non-White children (including part-White mixed-race children, of whom over 14 million were born in the half-century 1970–2020), and White spouses of non-Whites, would be permitted, but not required, to live with their children and spouses in the multiracial nation. Other Non-Hispanic Whites who might prefer to live in the multiracial nation could make their own arrangements to do so dependent on the multiracial nation’s consent.

This plan would require the relocation of circa 131.2 million people — 34 million or 17.5% of Whites and 97.2 million or 61.4% of non-Whites — and their personal property (see details in Appendix). As large as these numbers are, in a previous essay I calculated that the transportation logistics of relocating 150 million people and their personal property in a time frame as short as a year is feasible.

One of my long-standing principles of racial partition[18], applied in my first two partition proposals (1983 and 1989), has been that the partition allow no multiracial states on the grounds that a multiracial state is not a legitimate racial entity and therefore should have no standing in a plan for racial partition. My primary concern behind this principle was not that the non-White groups would be united in a multiracial state, but that allowing a multiracial state would be misused to justify the retention of most of the country’s White population and territory in a multiracial state that would divide the White race and be the primary successor and continuation of the United States (e.g., Michael Hart’s proposal discussed above). A secondary reason was the assumption that each of the non-White races would prefer to have separate monoracial countries like the White population and that fair and equal treatment should accommodate this. Except for the aboriginal Amerindian population, for which I continue to propose a separate country of their own, I now think this assumption may be incorrect — essentially a projection of White racial interests onto non-White populations which they may not really share. Non-White groups have always supported multiracialism, and those who immigrated to the United States voluntarily did so knowing it was not a racial state for them and with no expectation it ever would be, and certainly those who immigrated after 1965 knew they were coming to a multiracial country. It therefore seems more likely they would prefer to be joined into a large multiracial state that would be a major country at the world level by every measure.

If the Black and/or Hispanic populations preferred separate states for themselves they could sub-partition the territory of the multiracial nation into separate racial states, possibly along the lines of my second (1989) proposal, following the white lines on the map with the Black nation allotted the circa 252,200 square mile territory north of the Colorado river and east of the New Mexico border, the Hispanic nation the 199,000 square mile area south of the Colorado river and as far west as the Arizona border, and a multiracial nation for Semi and Non-European Caucasians and the various Asian racial groups in the remaining 218,192 square miles. In this arrangement visibly part-White persons would be assigned to the nation of the majority of their non-White ancestry.

This proposal aims to attract maximum White support consistent with the goal of racial separation and independence while avoiding non-existential and potentially divisive issues. Territorially this means retaining most of the country, and especially the areas that are the more historically and culturally significant and where the great majority of Whites live. Ideologically and politically, this means that, other than as required for the purpose of racial preservation, there should be no changes to the American constitutional system until after the completion of the partition, when any proposed changes to their country would be decided by the newly all-White population consistent with its sovereign prerogatives.

Appendix: The Logistical Scale of Population Transfer

In 2020 the U.S. non-White population was 135.8 million. Add to this the 8.2 million non-Whites in Canada (7.7 million “visible”) and the North American non-White population totaled 144 million. Add to this the 49 million non-Whites in Europe (43 million in northwestern Europe, 2.5 million in Italy, 1.5 million in Spain not counting Hispanic non-Whites from Latin America, 2 million elsewhere) and 3.2 million non-indigenous non-Whites in Australia and there are at least 196.2 million non-Whites to be geographically and politically separated from Whites for a complete and sufficient solution that would fully secure White racial preservation and independence. The 4.3 million indigenous Amerindians would have their own separate nation, leaving 191.9 million non-Whites for the multiracial nation. Many of the postwar immigrant non-Whites, including many Hispanics and Asians in the U.S. and many Turks and Arabs in Europe, are still citizens of their countries of origin, or dual citizens, and even vote in its elections. Many others still have strong family connections in the “old country.” It might be presumed that they would have the option to return there if they chose to do so. How many have this option, and how many of them would choose to exercise it rather than resettle in a new non-White country? It could be ten million or more among the non-Whites in Europe, and twenty million or more in North America and Australia. If 20 million non-Whites (e.g., 12 million from the U.S., 6 million from Europe and 2 million from Canada and Australia) with the option to return to their original countries chose to do so, 18 million White parents, grandparents and spouses of non-Whites (circa 15 million from the U.S.) chose to live with their relations in the multiracial nation, and 3 million White Hispanics chose to live there with the non-White Hispanics, it would have a population of 192.9 million, with about 137.5 million of this total from the United States.

In 2020 the U.S. White population was 194.9 million, including 9 million Hispanic European Whites. Per the same scenario as the previous paragraph, if 15 million White parents, grandparents and spouses of non-Whites chose to live with their relations in the multiracial nation, and 3 million White Hispanics chose to live there also with the non-Hispanic Whites, the White American nation would have a post-partition population of 176.9 million.

About 34 million European Whites (including Hispanic European Whites), or about 17.5 percent of the total European White population of circa 194.9 million (including Hispanic European Whites), and about 38.6 million non-Whites, or about 28.4% of the total non-White population of circa 135.8 million, currently reside in the area designated for the multiracial and Amerindian nations.

[1] David Reich, Who We Are and How We got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past (New York: Vintage Books, 2019), 229.

[2] Rabbi Mark Winer, “An Unbreakable Alliance: African-Americans and Jews,” Sun Sentinel, October 5, 2020 https://www.sun-sentinel.com/florida-jewish-journal/opinion/fl-jj-opinion-winer-unbreakable-alliance-african-americans-jews-20201005-4nmwxdxqtne2bowttok4xpojda-story.html

[3] Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: the Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, Vol. 1 (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1944), 167.

[4] Ruth Benedict and Gene Weltfish, The Races of Mankind, Public Affairs Pamphlet no. 85, 3rd ed. (New York: Public Affairs Committee, Inc., 1961), 11.

[5] Katarzyna Bryc, Eric Y. Durand, et.al., The Genetic Ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4289685/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gene_Weltfish

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aFZf_QGYCkM

[8] Phineas Eleazar, “Interracial Marriage & White Genocide,” Counter-Currents, December 6, 2019. https://www.counter-currents.com/2019/12/interracial-marriage-white-genocide/#more-113519

[9] Richard McCulloch, “Confronting Our Genocide,” The Occidental Quarterly, vol. 18, no. 4 (Winter 2018—2019) 56.

[10] Ibid, 57.

[11] Ibid, 46.

[12] Richard McCulloch, “The Ethnic Gap,” The Occidental Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 1 (Fall, 2001) 82 and 87.

[13] “In narratology and comparative mythology, the hero’s journey, or the monomyth, is the common template of stories that involve a hero who goes on an adventure, is victorious in a decisive crisis, and comes home changed or transformed.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hero’s_journey

[14] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jewish_population_by_country

[15] Kevin MacDonald, Separation and its Discontents (Westport: Praeger Publishers, 1998), 268.

[16] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4mvXthKTmJE

[17] Abraham Lincoln, “Remarks on Colonization to African-American Leaders,” August 14, 1862. http://hd.housedivided.dickinson.edu/node/40448

[18] Richard McCulloch, “Separate or Die,” The Occidental Quarterly vol. 8, no. 4 (Winter 2009) 15-38, and Richard McCulloch, “Visions of the Ethnostate,” The Occidental Quarterly vol. 18, no. 3 (Fall 2018) 29-46.

“Guillaume Faye was indeed an awakener.”

“Guillaume Faye was indeed an awakener.”