It seemed like an act of desperation. Twenty-five years after the fall of apartheid, South Africa’s Whites were counting on a Black man to save them from the corruption and malignancy of Black-majority rule. Its failure should have surprised no one.

By all appearances, Mmusi Maimane was a South African Barrack Obama. Smooth and polished, he seemed like the ideal candidate to win just enough Black votes from the tottering ANC to fulfill the promise of a multi-racial democracy.

The Democratic Alliance (DA) had long been viewed as the party of White people, but that was a handicap when Whites were just eight percent of the population. The party traced its roots back to the Progressive Party, the liberal opposition during the apartheid era, but few Black voters cared about that. Instead, the party drew most of its non-White support from the nation’s “coloured” population, a mixed-race group that shared just one thing in common with the nation’s Whites: a mutual fear of Black domination in the allegedly harmonious “Rainbow Nation.”

Maimane was supposed to be the DA’s ticket out of this electoral dead end. The “Obama of Soweto” would lead them in the 2019 elections to a promised land where everyone would be treated equally and race no longer mattered.

It blew up in their faces.

The Afrikaners

It all could have worked out very differently. Nearly 30 years ago, in November 1993, President F.W. de Klerk convened his cabinet to inform them that he had accepted Nelson Mandela’s demands for majority rule in the new government. Upon hearing the news, Tertius Delport, one of his negotiators, was stunned. They had given in on virtually everything. Resolved to resign, he walked down the hall to confront the president directly.

When de Klerk opened the door Delport grabbed him by his jacket lapels and cried out, “What have you done? You have given the country away! You allowed children to negotiate!”

“What are you going to do?” de Klerk asked coolly.

“I intend to rally enough colleagues,” Delport answered. “Together with the Conservative Party caucus, you will no longer have a majority.”

“Then there will be civil war,” de Klerk responded.

It was not out of the question. De Klerk had always viewed the military with a mixture of suspicion and disdain. Many of them viewed him as a traitor. He had already removed Magnus Malan, his widely respected defense minister. In late 1992, he resolved to clean out the rest of the dissidents in the military ranks.

“We are not playing with children,” one of his ministers warned him. “We are governing because the Defense Force allows us to do so. … The top command could decide to get rid of us and seize power. And where are we then?”

That did not dissuade de Klerk. The following day, he suspended or forcibly retired 23 senior army officers in what later came to be known as the “Night of the Generals.”

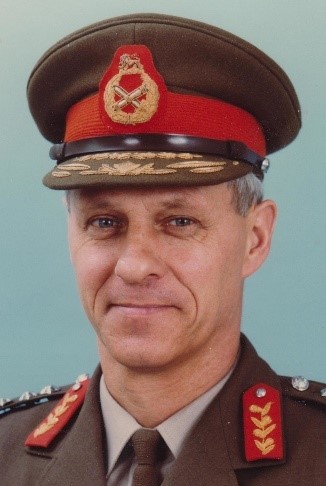

When retired General Constand Viljoen entered politics in 1994 to launch the Freedom Front, some viewed him as the country’s last chance. Many thought him capable of raising an army of up to 50,000 men from various defense forces and civilian paramilitary units that were loyal to him. Anticipating this, General Georg Meiring warned de Klerk and then met with Viljoen to sound him out.

When retired General Constand Viljoen entered politics in 1994 to launch the Freedom Front, some viewed him as the country’s last chance. Many thought him capable of raising an army of up to 50,000 men from various defense forces and civilian paramilitary units that were loyal to him. Anticipating this, General Georg Meiring warned de Klerk and then met with Viljoen to sound him out.

“You and I and our men can take this country in an afternoon,” Viljoen reportedly told him. “Yes,” Meiring replied, “but what do we do in the morning after the coup? The internal resistance and foreign pressures and the stagnant economy will still be there.”

For Viljoen, the lack of support from the armed forces was decisive. “I could have stirred things up in 1994—but for what purpose?” he later said. “I don’t think any action from my side would have resulted in a major part of the Defense Force siding with me.”

Viljoen’s decision was controversial among some Afrikaners, many of whom were more than willing to fight and die to save their country. Instead, Viljoen decided to use the threat of war to win an Afrikaner homeland — a volkstaat — by peaceful means. To placate him and his supporters, de Klerk and the ANC readily agreed to create a council to review the options. But it was just a ploy. Neither de Klerk nor the ANC ever took the idea seriously.

In the 1994 elections, the first held after the end of apartheid, Viljoen’s Freedom Front earned a little over two percent of the vote. The party was, and remains, an important voice for Afrikaners, as are advocacy organizations like AfriForum and Suidlanders, a civil defense group. But their power is limited by numbers. Whites are a small minority in South Africa. Conservative Afrikaners are just a minority within the minority.

Viljoen never had any illusions about this. His primary focus had always been the creation of an Afrikaner homeland. Consistent with the accord he signed with the ANC, a council was soon created to consider the creation of a such a volkstaat. But then, as now, the council soon faced a major obstacle: Afrikaners were spread too thinly across too many areas of the country for any single region to stand out as the obvious location.

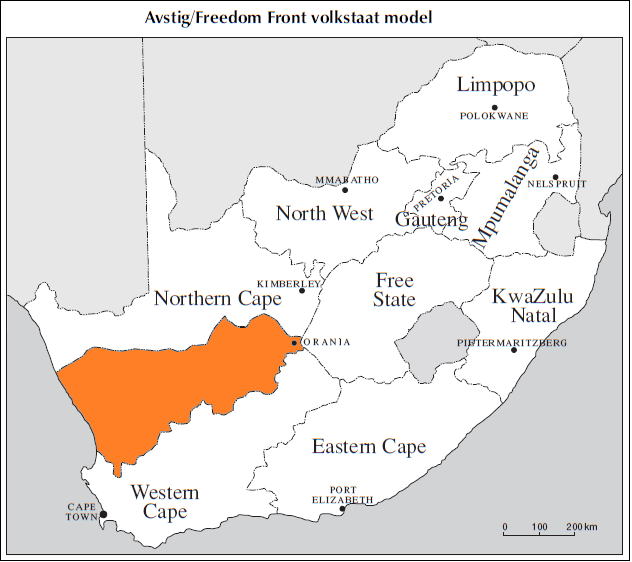

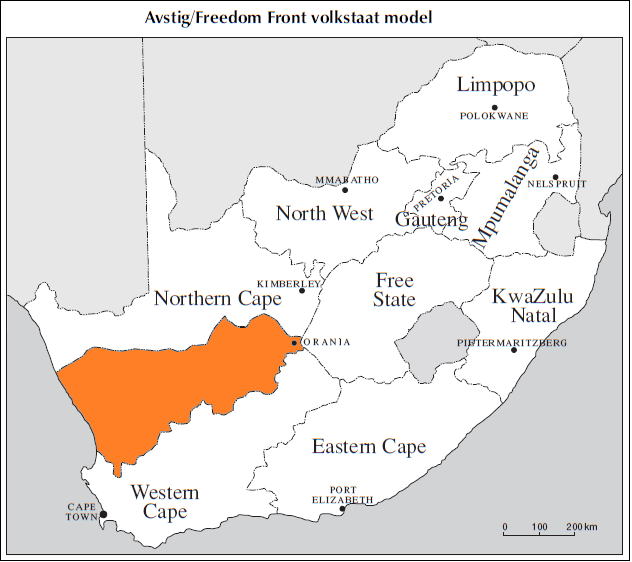

The council considered several options, including one based primarily in the Northern Cape that eventually drew the endorsement of the Freedom Front (shown in the map below). Other proposals included carve-outs in and around Pretoria, where the largest numbers of Afrikaners live.

But each of these proposals would have required large numbers of Afrikaners to uproot and move to the new state for it to be viable. Instead, a 1993 poll indicated that just 29 percent of White South Africans backed the creation of such a homeland. Just 18 percent said they would consider moving there if one were created.

“Afrikaners do not want their own homeland,” Johann Wingard, chair of the council, eventually concluded. “They want to live anywhere in their beautiful country where they can make a decent living.” Interest in the idea soon dissipated and the council was dissolved. For many, the dream of a volkstaat seemed dead and buried.

Carel Boshoff, son-in-law of former South African Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, had different ideas. In 1990 he bought a patch of land on the banks of the Orange River at the far eastern edge of the volkstaat proposed by the Freedom Front. The first few residents of the new Afrikaner town, called Orania, arrived the following year. The population has since grown to over 1,700, over a third of whom are children.

“They initially drew support from idealists,” said Dan Roodt, an Afrikaner activist. “They struggled financially in the beginning. In the early 2000s, you could buy a plot of land for a couple a hundred dollars. Now the price is 50 times that much.”

The town’s growth was powered by a strong desire for shared community and growing disenchantment with the rest of South Africa. It would have grown even faster if not for its commitment to using Afrikaner labor. “Orania does not use black labor,” Roodt said, “so it can’t build fast enough to build all the new housing they need.”

Orania had shown that the idea could work. And before long, public opinion would change.

Democratic Alliance

The Freedom Front — later renamed the Freedom Front Plus after it merged with the Conservative Party — was never the primary party of South Africa’s Whites. In the 1994 election, that distinction fell to the Nationalists under F.W. de Klerk. But there was also a third party contending for the White vote that year. The Democratic Party was barely a footnote, receiving fewer votes than the Freedom Front. But in time — and with the backing of most of the White establishment, the media, and a healthy dose of luck — it soon propelled itself forward to become the nation’s primary party for Whites, second in size only to the ANC.

In 1994, however, it was caught in a bind. Its traditional base of support had always been urban, politically liberal Whites. That became a problem when de Klerk lifted the ban on the ANC. Suddenly the party found itself being squeezed on both sides — by the ANC on the left, which drew away some of its White liberal support, and by the Nationalists on the right, who were viewed by most Whites as the only viable check against the ANC’s growing power.

Instead of capitalizing on this advantage, however, de Klerk fumbled it away. Thinking he could retain power and influence by working with the ANC, he allied with them in a post-election “unity government.” But this only alienated the Nationalists from their base of White voters. Worse, they were blamed for failing to stop the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which persecuted numerous White officials and military officers for their role in apartheid.

The Democratic Party took full advantage of the situation, challenging the Nationalists from the right in the 1999 elections. With the rallying cry “Fight Back!,” the party gained ground among White voters. After the election, the Nationalists continued to hemorrhage White support until 2005, when the party finally disbanded.

With its principal competition for White voters now gone, the newly renamed Democratic Alliance was free to expand its outreach to other racial groups, first to the “coloured” vote and later to the Black middle class. Like White establishment parties just about everywhere, it downplayed race and emphasized colorblind individualism and classical liberalism to maximize its cross-racial appeal. Using this strategy, it gained support in every subsequent election until 2014, when it peaked at 22 percent of the overall vote.

After that election, Helen Zille, the party’s leader, began looking for a successor. Her ideal candidate would be someone like Barrack Obama, who was then closing out his second term. Mmusi Maimane seemed to fit the bill. With Zille’s backing, he drew overwhelming support from the party in 2015. The party then marketed him in ways that amounted to virtual plagiarism — including blatantly copying Obama’s “Hope” poster and substituting Maimane’s image instead.

But Maimane did not play along. He was not interested in being the Black face of a White party. If the DA wanted his leadership to reach Black voters, then he would force it to swallow his message — and that message was one of Black nationalism.

In his acceptance speech, he warned the party that colorblindness was not enough. “These experiences shaped me, just like they shaped so many young Black people of my generation,” he said, echoing the criticisms of South Africa’s woke left. “I don’t agree with those who say they don’t see color. Because, if you don’t see that I’m Black, then you don’t see me.”

It was not long before Maimane was locked in a power struggle with senior members of his own party, advocating for affirmative action and straying from its emphasis on non-discrimination. Under his command, the party soon came to be seen as ‘ANC-lite,’ and the DA’s White leadership was not happy.

Neither were some of its other Black leaders, but for different reasons. ”I feel powerless when my activists come to me and say they are victims of racism from senior people in the party, who say they should be grateful that the DA keeps them busy because otherwise they would probably be out stealing and killing people somewhere,” one grumbled. “I mean, what is that?”

The DA paid the price for these divisions at the ballot box. In the 2019 elections, the party lost ground for first time since 1994, failing to gain any traction against the ANC and losing White voters on the right to the Freedom Front Plus. The ANC also lost ground, but not to the “colorblind” DA. Instead, it lost votes to the explicitly Black nationalist Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) under Julius Malema, who had pledged to “cut the throat of Whiteness.”

The lesson from the election was clear. In an increasingly chaotic nation, Black nationalism was the future. White voters and their parties had gone as far as they were going to go.

After the election, the knives came out. Helen Zille, the DA’s previous leader, was elected to a powerful party position by the old guard and she quickly challenged Maimane from within. Her predecessor, Tony Leon, chaired an internal party review that laid the blame squarely at Maimane’s feet. The Institute for Race Relations, an establishment-backed think tank, said he had abandoned the party’s cherished principles.

Maimane saw the writing on the wall, but he did not go quietly. At his resignation speech he called out the DA’s White leadership in explicit terms. “Over the past few months it has become more and more clear to me that there exists those in the DA who do not see eye-to-eye with me, who do not share the vision for the party and the direction it was taking,” he said. “There have been several months of consistent and coordinated attacks on me and my leadership, to ensure that this project failed, or I failed.”

Other Black party leaders followed him out the door. “I cannot reconcile myself with a group of people who believe that race is irrelevant in the discussion of inequality and poverty in South Africa,” said Herman Mashaba as he resigned from the party and as mayor of Johannesburg, the nation’s largest city.

Malema’s EFF released a gloating statement calling the DA a “White political party in which Whites and their interests as Whites must always dominate and come first.” Maimane was later seen hobnobbing with Julius Malema in what some called an emerging ‘bromance.’

Last November, the party overwhelmingly elected a new White leader, John Steenhuisen. He trounced his primary Black challenger, Mbali Ntuli, with 80 percent of the vote. The party, it seemed, was no longer pretending. Some are now questioning how it could possibly avoid a backlash by non-White voters in the next election.

Secession

Two decades ago, the idea of a White homeland in South Africa seemed dead in the water. Any area reserved for Whites that was too far away from the cities or from employment opportunities seemed impractical. Many Whites at the time also believed, or at least hoped, that South Africa would soon become the harmonious and prosperous multiracial nation that had been promised.

That hope is now gone. A worsening economy, ever-present crime, and rising corruption have all left their mark (detailed in my previous article, South Africa’s Protection Racket). According to public opinion polls, South Africans have grown increasingly pessimistic. The situation briefly stabilized when Cyril Ramaphosa replaced Jacob Zuma as president in 2018, but his promised reforms never materialized. Now public sentiment seems to be worsening again. The DA’s failed “colorblind” political strategy has only further darkened the mood among those who had hoped for more.

These negative views are most prevalent among Whites in general and in the Western Cape in particular, one of the few regions in the nation where Blacks are not a majority. In 2009, Whites in the province allied with the local coloured population and ousted the ANC in local elections. It has been ruled by the DA since then.

“Ever since the DA came to power in Cape Town and in the Western Cape one has heard a growing chorus from visitors that ‘It feels like a different (and better) country down here!’” wrote one local observer. “The public hospitals and schools work far better here than anywhere else in South Africa, the traffic lights work better, the city center is safer, there is less litter and generally there is better governance.”

Local rule was a step in the right direction, but some activists wanted more. In 2007, they formed the Cape Party to fight for genuine independence. The party never gained traction in the few elections it contested — partly because the timing was wrong and partly because voters inclined to support separatism already had a political home in the Freedom Front Plus.

Nine years of Jacob Zuma’s presidency changed that, however, and several new organizations have emerged. Following the success of the Brexit vote in Britain, CapeXit was founded in 2018 to seek independence through international law. Another organization, the Cape Independence Advocacy Group (CIAG), was launched in 2020.

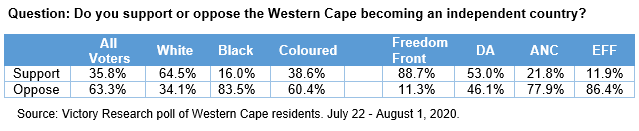

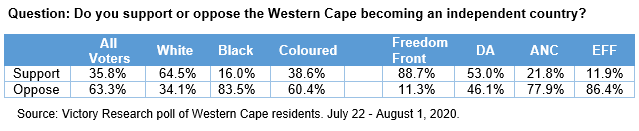

It seemed like public opinion had changed, but independence advocates decided to sponsor a poll to be sure. Unsurprisingly, the poll found overwhelming opposition among Black voters. But it also showed that Whites now strongly supported the idea, especially those who were supporters of the Freedom Front Plus.

Coloured voters — who constitute a majority of the Western Cape’s population — were more divided. While most were not yet ready to endorse full independence, the majority (68%) agreed that the Western Cape should be given more power to choose its own policies. Advocates now believe that this bloc of voters can be won over, particularly if the nation’s economy continues to deteriorate.

These poll results, which drew wide attention, have put the DA in a box. Much of its White leadership privately supports independence, but it has remained publicly silent to avoid alienating voters both inside and outside the province who do not support the effort. The Freedom Front Plus, which has endorsed independence, sees this as an opportunity. They plan to challenge the DA on this issue in the upcoming 2021 municipal elections.

Despite this growing support, however, some have condemned the independence movement as unrealistic. “Fringe groups have long advocated for the secession of the Western Cape from the rest of South Africa,” wrote Pierre De Vos, a constitutional law professor at the University of Cape Town. “Obviously, the Western Cape is not going to secede and there is no chance of the creation of an independent state.”

“Even if the Western Cape Premier calls a referendum (he won’t), and even if a majority of voters vote for secession (they won’t either), the referendum will have absolutely no impact as the president and his party will have no legal or ethical obligation to adhere to the results,” he wrote. Critics argued that the ruling ANC would inevitably reject Cape independence, not least because the Western Cape and Gauteng, the two provinces with the bulk of South Africa’s White population, provide most of the tax dollars that line the ANC’s pockets.

Supporters counter that international law, not the South African constitution, is the final word on the matter. “Countries secede on a regular basis, and the constitutional law of the parent state is almost never an insurmountable object if the other conditions required by international law are in place,” wrote Phil Craig, CIAG’s co-founder. Political will, not constitutional law, would decide this issue, as it has in nearly every other case of secession.

Bangladesh seceded from Pakistan despite the latter’s objections. Kosovo seceded from Serbia despite Serbia’s objections, and with the International Court of Justice advising that there is no prohibition of the (unilateral) declaration of independence under international law. Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Croatia, Slovenia, East Timor, South Sudan. The list goes on.

Closer to home, did the previous South African constitution prevent the end of apartheid, or Namibian independence? Countries secede on a regular basis, and the constitutional law of the parent state is almost never an insurmountable object if the other conditions required by international law are in place.

Whatever the objections, the politics of the issue are clearly trending in the supporters’ direction. Numerous economic experts and political analysts now see South Africa entering a death spiral. Last year, the nation lost its last investment-grade credit rating when Moody’s downgraded it to “junk” status. Investors have been fleeing the country for years. According to IMF estimates, unemployment is fast approaching 40 percent. The Covid crisis has only made matters worse, contributing to widespread protests. At least one analyst estimates that if its existing economic policies are not reversed, the country faces economic and political collapse by 2030.

Despite such warnings, President Cyril Ramaphosa seems powerless to implement needed reforms. According to analysts at the establishment-backed Institute of Race Relations, power in the ANC has now shifted decisively to leftist Black nationalists. If Ramaphosa were to challenge the party’s top leadership in any meaningful way, they would remove him from office.

This worsening economic and political outlook will only heighten public support for secession over time. The final trigger could be an independence referendum in the Cape, an IMF bailout that imposes cuts on ANC-favored spending priorities, a forced removal of Ramaphosa by the ANC leadership, or a national election that forced the ANC into a governing coalition with the far-left EFF to maintain Black majority rule.

Regardless of the cause, if the Western Cape seceded, it would probably trigger similar efforts in other parts of the country. This might include some or all of the Northern Cape, which has similar demographics and is home to Orania. Another possibility is the Whiter regions in and around Pretoria and Johannesburg, which might also demand increased local autonomy. Absent that, many of these Whites might flee to a newly independent Western Cape, just as Whites fled Zimbabwe to South Africa during Robert Mugabe’s reign.

The Rainbow Nation’s days may be numbered, but now there is something new to hope for. An independent Western Cape would not be the volkstaat — nor indeed an ethnostate of any kind. But it would at least free the nation’s White population from the worst excesses of majority Black rule and reestablish the right of self-determination.

When reporters travel to Orania, they sometimes ask the residents why they chose to move there. “We want to build a better place for our children and ourselves,” one recently said.

It is a simple answer, one that anyone could have given, but now more people are beginning to realize that it is something that cannot be taken for granted. Self-rule has long been an aspiration for many White South Africans. Now, after all these years, it may finally be within reach.

Patrick McDermott is a political analyst in Washington, DC.

Tito Perdue, Love Song of the Australopiths, 2020)

Tito Perdue, Love Song of the Australopiths, 2020) ndence with the Jews, were also the most consistent adversaries of Jew-baiting.

ndence with the Jews, were also the most consistent adversaries of Jew-baiting.

When retired General Constand Viljoen entered politics in 1994 to launch the Freedom Front, some viewed him as the country’s last chance. Many thought him capable of raising an army of up to 50,000 men from various defense forces and civilian paramilitary units that were loyal to him. Anticipating this, General Georg Meiring warned de Klerk and then met with Viljoen to sound him out.

When retired General Constand Viljoen entered politics in 1994 to launch the Freedom Front, some viewed him as the country’s last chance. Many thought him capable of raising an army of up to 50,000 men from various defense forces and civilian paramilitary units that were loyal to him. Anticipating this, General Georg Meiring warned de Klerk and then met with Viljoen to sound him out.